Fighting Back to Protect Student Voting Rights

abstract. Many people bemoan the relatively low voter-turnout rates in the United States, particularly among younger generations. However, student voters face a wide variety of obstacles that can deter them from democratic participation. Some of the oft-discussed obstacles include jurisdictions not accepting student ID cards for the purposes of voting and making it difficult for students to register to vote at their university addresses. An additional problem that deserves further attention is the lack of on-campus voting opportunities for college and university students, and the intentional efforts in some jurisdictions to further limit those opportunities. This Essay examines the problem through the lens of the author’s on-the-ground experiences as a public-interest legal fellow working on election and voting-rights issues in Texas. It surveys several on-campus voting issues from the 2018 midterm elections and discusses possible avenues for fighting back against efforts to suppress student voters.

Introduction

Complaining about the lack of youth-voter engagement in America is a traditional postelection pastime. This Essay takes for granted that greater voter participation is desirable in a democracy1 and explores one set of causes underlying poor youth turnout. The 2018 midterm elections saw a moderate surge among voters aged eighteen to twenty-nine, with the largest turnout increase since the last midterm election coming from this demographic.2 Nevertheless, eighteen- to twenty-nine-year-olds remained the lowest-voting age group, turning out at barely half the rate of those over sixty-five.3 A wide range of factors contributes to the lack of youth turnout. Among other things, young people juggle a wide variety of academic, professional, and social responsibilities; and they face unique psychological challenges.4 But low youth turnout is not a global phenomenon,5 and the age gap in turnout rates varies greatly from country to country.6 This variation strongly implies that policy choices can have significant effects on youth-turnout rates.

Many U.S. states and localities have taken meaningful steps to make it easier for students to vote. Some efforts directly benefit student voters, such as designating student ID cards as a valid form of voter ID7 and pre-registering sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds to vote.8 Additionally, broad-based policies that make voting easier for all citizens benefit student voters who face unique obstacles, including a lack of transportation, knowledge about registration requirements, and prior electoral engagement. These policies include same-day voter registration, automatic voter registration, and universal vote-by-mail laws.9

Despite these improvements, major hurdles remain. Others have written about the challenges that young voters face due to restrictive photo ID laws, which prohibit the use of even state-issued student ID cards.10 There has also been considerable academic and legal debate on where students should register to vote.11 Although generally courts have become more sympathetic to students seeking to register to vote at their school residence,12 new, ever-inventive prevention strategies raise perennial questions about which residency requirements states and localities can impose on students.13 This perennial fight occurs because of student voters’ left-leaning partisan valence.14

Although it has received relatively little attention in the literature,15 I have learned through my experience as a Yale Law Journal Public Interest Fellow in the Voting Rights program at the Texas Civil Rights Project that the lack of physical access to polling locations is a major obstacle for young voters. This lack of access can be the direct result of actions by governing bodies (such as removing or failing to provide on-campus polling locations) or the indirect result of combinations of policies (such as a combination of purposeful campus gerrymandering and strict rules regulating which precincts residents must vote in).16 This Essay aims to illustrate the problems facing on-campus voters, to survey existing practical and legal remedies, and to consider policy solutions that might be implemented to address these problems at the state and federal level.

Part I begins by surveying several distinct campus-polling problems that I have encountered during my time as a Fellow, in particular, as part of the Texas Civil Rights Project’s Election Protection program during the 2018 midterm elections.17 First, I discuss the problematic effects of campus gerrymandering. Second, I examine the lack of on-campus polling locations. Last, I look at recently passed state laws that appear to present neutral, perhaps even commonsense, policies, but that are, in reality, an attempt to limit on-campus voting opportunities for students at midsize or smaller campuses.

Part II looks at some of the legal and practical tactics that have proven successful in combating campus polling restrictions. One must first assess whether litigation would be a component of a successful strategy and, if so, when to file, where to file, and which claims to rely on. The Essay explores how some of these factors played out in successful attempts to expand access for on-campus voters. It then examines potential policy solutions at the local, state, and federal levels. These include proactive local reforms as well as resistance against states’ attempts to counteract positive local efforts.

I. problems at the polls

A. Campus Gerrymandering

Because university campuses often hold a geographically consolidated group of demographically distinct potential voters,18 they present an easy opportunity for mapmakers to drastically skew districts’ political or racial dynamics. In smaller election contests, a large residential campus can account for a majority of a district’s voting-age population. The decision to place a university campus in a specific district can itself represent a gerrymander—for instance, when an entire municipality lies in one district but the local campus has been carved out and joined with other communities. Further, politicians can refine their gerrymandering efforts by splitting campuses between political units. Beyond distorting the representational power of university voters, such gerrymanders can create practical complications that undermine the integrity of elections.

As part of the decennial redistricting process, Texas counties often redraw their election precinct lines.19 This occurs in part to conform to new legislative maps, and in part to comply with state limits on how many registered voters can live in a precinct.20 While the state-level redrawing of electoral districts—particularly in a state such as Texas, with a long history of discriminatory gerrymandering—draws intense public and legal scrutiny, these hyper-local processes go largely ignored. This is especially true when it comes to the drawing of precinct lines, as opposed to district maps, for local elected offices. Nevertheless, there can be significant real-world consequences.

Although some states and counties allow individuals to vote at any polling place within the county, or by mail,21 many still require individuals to vote at the polling place tied to their address. This invariably causes confusion on Election Day and, in jurisdictions with strict laws, results in thousands of provisional ballots that ultimately get tossed aside for being cast at incorrect polling places.22 Precinct assignments also determine which elections an individual can vote in.23 As demonstrated in the following example, combining complicated rules around precinct-based voting with extreme gerrymandering and poor election administration can lead to harmful results.

Texas State University (TSU) is a large public university in Hays County, Texas. TSU is home to 38,661 students, over 7,000 of whom live on campus,24 with thousands more living in private housing in the immediate vicinity. The student body represents roughly 17% of the entire Hays County population.25 While not all students choose to claim residence in Hays County, students still make up an undeniably large proportion of the county’s total population.

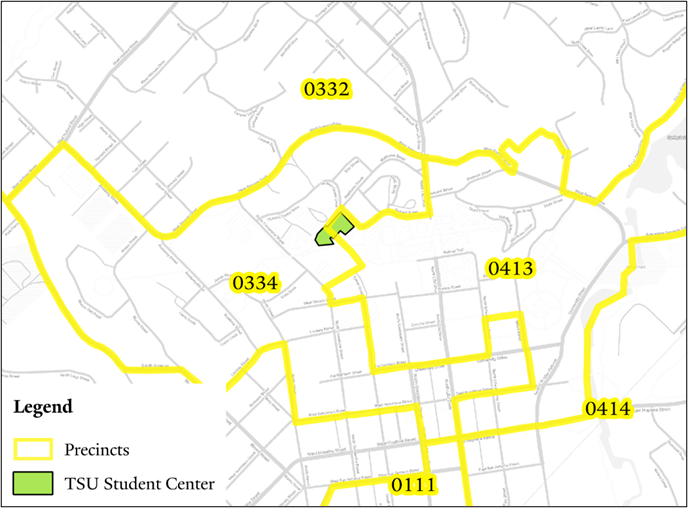

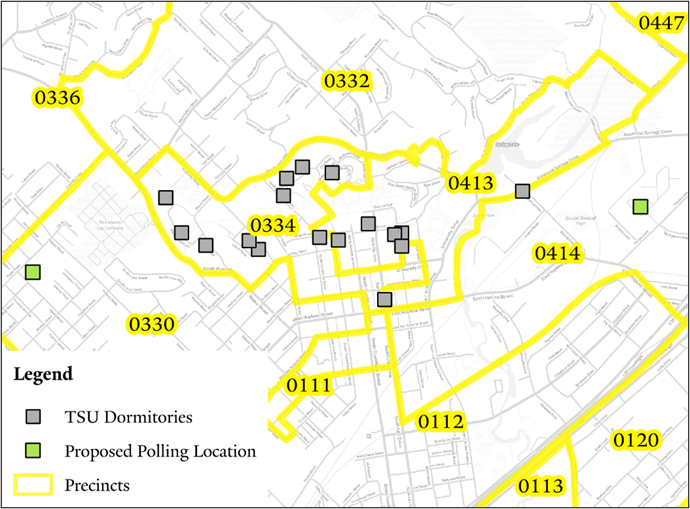

Figure 1 represents the current election precinct boundaries in Hays County. The lines are winding, though at first glance they may not look inherently illogical. However, overlaying features of the campus reveals the distorted way in which the community is carved into different precincts. Some of what appear to be streets on the precinct map are in fact merely paper streets26 or walking paths. Perhaps the most absurd result is that the Student Center, which has housed the only on-campus voting location ever used, is bisected by the precinct lines. Figure 2 shows where many of the major on-campus residences are located—a confusing distribution between precincts by any measure, with no clear or logical dividing lines for which residential halls are assigned to which precinct.27

FIGURE 1.

|

FIGURE 2.

|

My involvement in the TSU on-campus voting landscape began during the early-voting period when students and organizers on the campus began calling the Election Protection hotline to complain about the closure of the TSU on-campus early-voting location after only three days of early voting.28 In Texas, early voting is more lax than Election Day voting, and voters are allowed to cast a ballot at any location in the county.29 While investigating the early-voting situation, I also realized that there were no planned on-campus voting sites for Election Day, despite there being two large voting precincts that were comprised primarily of the campus.

Figure 2 also shows Hays County’s proposal for the intended placement of its Election Day poll sites prior to our threatening litigation. State law permits combining precincts into one polling place under certain circumstances.30 The county originally intended to combine each of the two primarily on-campus precincts with two off-campus precincts, meaning that students in those precincts would have to travel off-campus (approximately 2.2 miles in one case and 1.7 miles in the other) to cast their ballot. On top of figuring out the complicated and illogical assignment of residence halls to different precincts, students (many of whom lack transportation) would have had to find a way to get to these polling locations. One of the polling locations is separated from campus by a highway. If a student showed up at the wrong location, she would have to travel 3.4 miles in the opposite direction to reach the correct location.

I discovered, however, that the county had acted improperly by ignoring a provision of state law limiting the number of registered voters that can be combined into a single polling place.31 The larger of the two on-campus precincts, it turns out, had been improperly combined with a different large off-campus precinct. In addition to addressing the early-voting closures, the Texas Civil Rights Project wrote a legal demand letter to the county on behalf of two nonprofits, informing the County of its illegal combination of polling places. In the face of threatened litigation, the county agreed to open an on-campus polling place for this particular precinct. But voters from the other main on-campus precinct were still required to travel off campus to vote.

The confusion on Election Day was compounded by the fact that massive voter-registration efforts had created a backlog of registration applications in the county. Many students did not receive their registration certificates, which indicate their precinct assignment, ahead of Election Day. Although they were entered into the system, they would have had to visit the county website or contact the county directly to determine their precinct.

This campus gerrymandering led to significant confusion. Reports from Election Day indicate that many students showed up to vote at the incorrect polling place, and some reports indicate that election workers may have provided misinformation.32 According to the reports, the poll workers either unnecessarily directed students to make trips back and forth between polling places, or said they could cast a provisional ballot if they were at the wrong location without explaining that their ballots would not be counted. One measure of this confusion is the number of provisional ballots cast in Hays County. There were 1,316 provisional ballots in the county,33 which has a total population of 222,631.34 This is compared to 2,794 provisional ballots in Dallas County, which has a total population of 2.63 million, and 857 in Bexar County, which has a total population of 1.98 million.35 Of these 1400 provisional ballots, 1,168 were rejected.36 However, the confusion and lost votes were only one manifestation of the ill effects of campus gerrymandering at TSU and, perhaps, not even the most egregious.

Given the extreme gerrymandering of the campus, it is no surprise that students were confused about which precinct they live in or where they should vote. As was revealed in the 2018 midterm elections, even county election officials could not keep their lines straight, in the most literal sense. After the 2018 midterm election, I, on behalf of the Texas Civil Rights Project, filed open-records requests with the County Election Department regarding the assignment of voters in on-campus precincts. The responsive documents indicated that, for the entire twelve-day early-voting period, individuals residing in one residence hall were incorrectly programmed in the county system as residing in the wrong precinct.37 Because this error took place during early voting, when voters can cast ballots at any polling location in the county, it did not affect the voters’ ability to cast a ballot. However, it did affect which races they could vote in. Being assigned to the wrong precinct meant that these students voted in the incorrect U.S. Congressional and County Commissioner contests, in addition to some local races.38 At least 114 voters cast ballots in the incorrect precinct.39 The County Commissioner races for Precincts 3 and 4, which were the two Commissioner races affected by this mix-up, were decided by thirty-seven and 1,201 votes respectively.40 Thus, this precinct confusion may have materially affected at least one election result.

Although I draw on the TSU example due to my personal experience with the situation, this is hardly an isolated incident. In this midterm election, there were also problems at Prairie View A&M University, a historically black university in Waller County, Texas with a total enrollment of 9,516 students.41 Waller County has a total population of 53,126, therefore, this campus makes up a sizable percentage.42 Waller County has a noted history of voter-suppression efforts aimed at Prairie View A&M and has been found to have violated the voting rights of Prairie View students with both racial and age-based discrimination.43 Issues arose this election cycle because the university does not provide individual mailboxes for students; instead it assigns them each a P.O. box. Thus, they do not have a physical address at which they can register. In recognition of this problem, the university instructed students to use one of two possible physical addresses on their voter-registration forms. However, the addresses were located in two different precincts, with one assigned to an on-campus voting location and the other to an off-campus location. Although a resolution was ultimately reached that allowed student voters to complete a change of address form when going to vote on campus, it required students to complete extra paperwork.44 Campus gerrymandering has also prominently featured in the ongoing controversy over North Carolina’s last decennial redistricting.45 And plaintiffs in the current Ohio partisan gerrymandering case have pointed to the confusion caused by unnaturally dividing college campuses.46

B. Lack of On-Campus Polling Places

A great deal of harm comes from simply failing to provide polling locations on campus regardless of whether the campus has been gerrymandered. At TSU, the problems with precinct-level gerrymandering were perhaps more dramatic in that they directly undermined the integrity of election results in at least two close races. But the original complaints that brought TSU to the attention of the Election Protection hotline dealt with the County closing the on-campus early-voting location after only three days.

From Monday, October 22 through Wednesday, October 24, 2018, Hays County operated a temporary early-voting site at the TSU Student Center. Over this period, 2,965 voters (presumably mostly university students) utilized the location.47 On the third and final day of on-campus voting, waits of over an hour persisted all day and the site was the busiest early-voting location in Hays County.48 Per the original Hays County plan, TSU students (whose 2018 undergraduate enrollment was 34,187)49 were provided with only twenty-four hours of on-campus voting time. This contrasts with the students at the comparably-sized nearby University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) (with a 2018 undergraduate enrollment of 27,312)50 and University of Texas at Austin (with a 2018 undergraduate enrollment of 40,804).51 UTSA students were provided with 128 total hours of early voting52 and UT Austin students were provided with 276 (138 hours each at two separate locations).53 Of course, Hays County had posted its plans for early voting ahead of time, but the fact that nobody caught the problem highlights one reality of election protection work: it is impossible for any organization or group of organizations to be apprised of all of the on-the-ground factors in every jurisdiction across a state—particularly one as large as Texas, with 254 counties where a variety of locally appointed and elected officials administer elections depending on the county’s size and resources.

Nevertheless, after receiving complaints, I found a seldom-mentioned section of the Texas Election Code—one which appears to have never been the subject of prior litigation—that regulates how many early-voting locations can be established in each County Commissioner’s precinct (each Texas county is broken up into four such precincts) in counties of a certain size.54 For counties the size of Hays, the law requires that no County Commissioner precinct have more than twice as many early-voting locations as any other precinct. After some amateur mapmaking, I was able to determine that Hays County had placed three early-voting locations in one County Commissioner precinct, and, after the closing of the TSU early-voting site on the third day, there would be only a single early-voting location in another. We sent a demand letter to the county threatening litigation55 and coordinated with local grassroots groups to launch a public pressure campaign, including placing over a thousand phone calls from constituents to their local county elected officials in one day. The next day, in an executive session, the County Commissioners decided to reopen the on-campus early-voting site as well as open an Election Day site to remedy the improper combining of precincts described in Section I.A.56

The reopening of an on-campus voting location proved fruitful for Hays County voters. The TSU location was the busiest early-voting location in the county when it reopened.57 Precinct 334, where we succeeded in both extending the days of operation for the early-voting location and in getting an Election Day location opened, saw the largest midterm-to-midterm increase of any election precinct in the County, with students turning out at 400 percent of the level they did in 2014.58 Based on this limited anecdotal evidence, it would appear that students will vote when you give them a reasonable opportunity to do so.

As with campus gerrymandering, the TSU incident was not isolated. Indeed, many of the same places where campus gerrymandering has occurred have also faced allegations of discriminatory closure or refusal to open on-campus polling places. The district court in Shelby County v. Holder cited Waller County’s attempt to close an on-campus Prairie View A&M early-voting site as evidence of the ongoing need for the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance provisions.59 Another lawsuit during the most recent midterm elections was necessary to get Waller County to provide the Prairie View campus with adequate early-voting opportunities.60 North Carolina State University, with a total enrollment of 35,479,61 lost its early-voting location in 2014, following the Supreme Court decision in Shelby County.62 In Florida, neither Florida State University nor Florida A&M, both located in Tallahassee, have early-voting locations, despite a combined enrollment of nearly 50,000 students.63 In 2014, the Florida Secretary of State even issued an election-law opinion that would have prevented any university buildings from serving as early-voting sites. But a federal court enjoined this opinion, finding that it was likely motivated by unconstitutional age-based discrimination, in contravention of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment.64

C. Restrictions on Mobile Voting Sites

For major universities with tens of thousands of students, there is a demonstrable demand and need for dedicated polling places throughout early-voting periods and on Election Day. Providing these campuses with dedicated voting sites is all the more logical (at least from a non-partisan, pro-participation standpoint) when they make up a significant percentage of the total population of the surrounding county or city. However, students at smaller universities, particularly those within larger counties, face unique problems. It is often not financially efficient or realistic to keep a polling place open on campus every day of early voting to serve a population of, for example, 2,000 students in a county with a population of over one million. Nevertheless, these students often face the same lack of transportation as students at larger campuses, and the problems could be exacerbated as public transit between these smaller campuses and other parts of the community may be suboptimal. Some counties wishing to serve these populations have come up with inventive solutions, utilizing so-called mobile early-voting sites that rotate between locations.65 Not only can these mobile sites serve smaller campuses, but they can be rotated to rural regions or communities that face difficulty getting to the polls, such as the elderly.66 Although the term “mobile voting” may conjure up images of a voting trailer,67 these temporary sites are typically housed inside existing buildings but only operate for certain days or hours.

Despite these creative solutions, or perhaps to intentionally undermine them, states have cracked down on counties’ ability to employ mobile voting. In 2018, the North Carolina Legislature overrode a gubernatorial veto to enact Senate Bill 325, which requires counties to keep all early-voting locations open for a uniform set of hours and days.68 Analysis of this law’s effect in the 2018 midterm elections indicates that forty-three of North Carolina’s one hundred counties eliminated at least one early-voting site, almost half reduced the number of weekend days, and about two-thirds reduced the number of weekend hours, compared to 2014.69 The reduction in locations appears to have had a particularly dramatic impact on youth-voter-turnout rates.70

During its most recent legislative session, Texas passed a similar law, House Bill 1888, which went into effect on September 1, 2019.71 HB 1888 requires every early-voting location in a county to remain open for the same weekdays and hours as the county’s “main early voting place.”72 The stated intention of the bill’s author was to crack down on school boards strategically targeting school events, such as PTA meetings, to garner support for elections to approve spending bonds for the local district;73 but the author’s refusal to entertain amendments that would have provided exceptions for university campuses, city halls in rural communities, and elderly living centers, reveals a more nefarious intent.74 The stark effects of this bill on student voters, if it remains unchallenged and counties do not expend the funds necessary to comply with it, are already becoming apparent.75

II. avenues for combating student-voter suppression

In the preceding Part, I surveyed a particular set of student-voter challenges—those related to voting on campus, drawing on personal experience from the 2018 general election. I focused on this set of problems both due to my personal observation of their salience and because it seemed like a topic that heretofore had received scant attention in the literature. In this Part, I consider some of the avenues available for combating the attempted suppression of student voters. First, I look at the role of litigation, discussing potential benefits and drawbacks and surveying some of the relevant decisions that one must face when choosing to litigate this set of issues. Next, I turn to potential policy and advocacy avenues for both reactively and proactively combating student-voter suppression.

Although courts undeniably play a major role in protecting voting rights and solving election-related disputes, seeking judicial relief as a first order of business may not always be the most effective solution. One lesson from my election-protection work is that, despite increasing interest in and awareness of these issues, there are still limited resources available, particularly when it comes to providing in-depth answers to tricky election-law questions and troubleshooting complex problems. Emergency election litigation is a time- and resource-intensive process. One Election Day lawsuit that we filed against Harris County, Texas to keep its polls open late76 took the full attention of three attorneys working almost exclusively on this issue for over half of Election Day. Given that we only had a staff of seven dedicated voting-rights attorneys, this was a significant diversion of resources away from responding to voters’ and volunteers’ questions. Particularly given the projections of record turnout in 2020,77 resource availability must be factored into any decision to file suit.

Additionally, litigation involves running through a complex, uncertain decision-making matrix. One initial key decision is determining where to file, namely federal or state court. Though federal courts have often been the venue for voting-rights impact litigation, state courts can offer some attractive features. State election laws can be a complex quagmire of provisions passed over hundreds of years, some of which may be remnants of previous eras. Although this complexity itself can be a source of voter confusion, local governments can also unwittingly run afoul of these multifarious requirements. Litigators can use these more technical violations as leverage to achieve substantive outcomes, such as our leveraging the violation of Texas’s early-voting location laws to convince the County to reopen the on-campus early-voting site.78 In contrast, federal constitutional doctrines tend to be abstract. For instance, one of the primary tools in federal voting-rights litigation relies on a balancing test to compare the burdens of a particular governmental action to the state’s interest in that action.79 Although potentially useful, such open-ended tests lend themselves to unreliable outcomes.80

Of course, federal courts are still an important tool, and often the only reasonable one available. There is, perhaps unsurprisingly, evidence that when judges are elected on a partisan basis, as is the case in many states,81 their decisions in election-law cases have a partisan valence.82 Though an individual’s or organization’s interest in protecting student voting rights might be strictly nonpartisan, it would be foolhardy to not realize that the only reason certain officials seek to suppress student voting is because of its partisan effects. And, depending on the facts at issue, federal claims may be the strongest. For instance, bringing a Voting Rights Act claim in a jurisdiction with a noted history of intentional racial discrimination against students at a historically black college might make more sense than trying to mount the same challenge from scratch in a state jurisdiction where the issues have never been litigated. Although state courts should have jurisdiction to enforce these federal claims, it might be more useful to appear in front of a judge familiar with the legal issues at play.

The timing of the litigation also comes into play. If a jurisdiction has a state court of last resort that is notably inclined to take a restrictive view of voting rights, one must assess how likely the case is to make it up to that court in time for meaningful review. If the litigation is of an emergency nature, any review beyond the lower state court’s initial decision on a temporary injunction may be moot by the time it reaches an appellate court.83 That is not to suggest that parties should intentionally delay filing claims until there is no time to appeal—among other things, such a decision might raise laches issues.84 But, due to the aforementioned nature of election litigation, these issues often do not come to light until voting is already underway, and certainly a court would not fault a party for at least giving a jurisdiction a reasonable period of time to choose to comply with a formal demand prior to having litigation filed against them. Even if a federal court might otherwise be the ideal choice for litigating a particular issue, they are not known for their speed or efficiency, and, for understandable federalism reasons, may have concerns about disrupting state elections close to the beginning of voting.85 All of these venue and timing considerations merely serve to underscore the complexity and inherent unpredictability of litigation.

As demonstrated by the TSU situation, a well-laid-out threat of litigation combined with public and media pressure might be sufficient to compel a county to act. Although, undoubtedly, many government actions aim to disenfranchise student voters—regardless of whether the motivations are inherently partisan, racial, or otherwise—some problems arise simply from poor election administration. For instance, although the conditions for the problem were created by campus gerrymandering, there is nothing to indicate that assigning students to the wrong precinct during early voting was an intentional act of discrimination as opposed to an administrative error. In determining the best course of action, it is also important to distinguish between which county officials are responsible for which election decisions. For instance, while the addition or subtraction of polling places might be the responsibility of elected officials in one jurisdiction, it might be the responsibility of a local bureaucrat somewhere else. The relative effectiveness of public pressure versus a threat of litigation may vary depending on where the power for the decision rests. Nevertheless, there may be situations where the entity in charge of elections refuses to remedy a problematic situation and litigation is necessary.

As recent developments in Hays County have demonstrated, sometimes the best defense is a good offense. The most direct way to get on-campus polling places secured is to start early and apply pressure. The fact that often these hyper-local decision-making processes get scant attention increases organizing efforts’ ability to make an impact. Going into the November 2019 elections, Hays County community members became concerned about apparent plans to move the popular on-campus voting site to a more remote and obscure location.86 However, armed with knowledge that this might be a problem, students and community groups were able to catch the problem before locations were finalized and effectively advocate for dedicated on-campus voting sites for all of early voting and election day.87 Even if such advocacy efforts are unsuccessful, they can nevertheless help build a record for future litigation that hinges on the intent of county election officials to disenfranchise students, particularly where the student population represents a community of color in an otherwise majority-white jurisdiction.88

However, as evidenced by the passage of anti-mobile polling place laws in North Carolina and Texas, state legislatures can stand in the way of positive local reform efforts. Increasingly, the right to vote is itself becoming an election issue.89 This has provided momentum to organize against voting-rights attacks and successfully block anti-voter bills. For instance, in Texas, a coalition of grassroots and civil-rights groups organized to help defeat Senate Bill 9, an omnibus election bill that, among other things, would have made it easier to convict individuals of voter fraud for innocent mistakes.90 This defeat came despite the Lieutenant Governor prioritizing the bill’s passage.91

In sum, although traditional defensive tools, such as litigation and the threat thereof, will continue playing an important role in the fight for student voting rights, proactively organizing before problems materialize is the ideal course of action.

Conclusion

Given the stakes of the 2020 election, the issue of student voter suppression is sure to arise in various measures, including those limiting on-campus voting opportunities. Although there has been some successful litigation to prevent governing entities from closing polling sites, it often comes in the form of emergency election litigation, and a robust case law has yet to emerge. Undoubtedly, litigation will play a necessary role in protecting the rights of student voters. However, it would also be wise for advocates and affected individuals to start early to identify areas of need and coordinate campaign plans. For example, presenting a strong case for a campus polling site at local election hearings can set the stage for successful litigation later by undermining the governing entity’s purported justifications for denying access to student voters. 92 Across the board, the best bet for giving students access to the polls might come in the form of coordinated local advocacy well in advance of actual elections.

Joaquin Gonzalez is a Staff Attorney with the Texas Civil Rights Project. At the time of this Essay, he was a Yale Law Journal Public Interest Fellow working on voting rights at the Texas Civil Rights Project. The author thanks Jake van Leer and the editors of the Yale Law Journal Forum for their hard work and insight, and Rebecca Harrison Stevens, Ryan Cox, and Hani Mirza for their guidance and assistance in navigating the events described herein.

A majority of Americans appear to share this view. See Drew Desilver, U.S. Trails Most Developed Countries in Voter Turnout, Pew Res. Ctr.: Fact Tank (May 21, 2018), https:// http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/05/21/u-s-voter-turnout-trails-most-developed -countries [https://perma.cc/3UW2-FJBA] (“[M]ost Americans—70% in a recent Pew Research Center survey—say high turnout in presidential elections is very important . . . .”).

Jordan Misra, Voter Turnout Rates Among All Voting Age and Major Racial and Ethnic Groups Were Higher than in 2014, U.S. Census Bureau (Apr. 23, 2019), https://www.census.gov /library/stories/2019/04/behind-2018-united-states-midterm-election-turnout.html [https://perma.cc/SH24-JQ4M].

See, e.g., Marilyn Price-Mitchell, The Psychology Behind How Young People Vote, Psychol. Today (May 23, 2016), https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-moment-youth /201605/the-psychology-behind-how-young-people-vote [https://perma.cc/EHB2-DJ4E] (“arguing that most candidates do not appeal to young voters”).

Countries with the Highest Voter Turnout, WorldAtlas (May 25, 2018), https://www .worldatlas.com/articles/countries-with-the-highest-voter-turnout.html [https://perma.cc /T3T4-8Y4W] (“Another notable factor [in South Korea’s high voter participation rate] was the high youth voter turnout at 70% of the youth between ages 19-29 years, and this could be credited to the number of youth outreach programs such as celebrity endorsements, mock Election Days, and media advertising that may have made the youth turn out to vote in large numbers.”).

Youth Voter Participation, Inst. Democracy & Electoral Assistance 27 (1999), https:// http://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/youth-voter-participation.pdf [https://perma .cc/N72U-BQVS].

Of the states that have a photo ID requirement, nine allow some form of a student ID card. Wendy Underhill, Voter Identification Requirements, Nat’l Conf. St. Legislatures (Jan. 17, 2019), http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/voter-id.aspx [https:// perma.cc/9JXU-CGGF].

Michael P. McDonald, Voter Preregistration Programs, Comp. Study Electoral Sys. 1-3 (2009), https://cses.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/CSES_2009Toronto_McDonald .pdf [https://perma.cc/YF52-G997]; see also Oregon Motor Voter Act FAQ, Or. Sec’y St., https://sos.oregon.gov/voting/pages/motor-voter-faq.aspx [https://perma.cc/S7GT -CCWR].

See generally Same Day Voter Registration, Nat’l Conf. St. Legislatures (June 28, 2019), http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/same-day-registration.aspx [https://perma.cc/X9BN-N9GF] (describing same-day voter registration and surveying state policies).

E.g., Nathaniel Cary, Furman Students Will Get to Vote After Judge Issues Injunction, Greenville Online (Oct. 7, 2016, 6:44 PM ET), https://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/news /politics/2016/10/07/judge-orders-greenville-county-stop-issuing-questionnaires-college -students/91742114 [https://perma.cc/QB27-P48J] (describing a South Carolina judge blocking the use of invasive questionnaires directed at students seeking to register on-campus); Paul Egan, College Democrats: State Laws Discriminate, Make It Too Hard to Vote, Detroit Free Press (Aug. 31, 2018, 4:31 PM ET), https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan /2018/08/31/college-democrats-michigan-voting-laws/1155854002 [https://perma.cc/QXU7 -VM95]; Dave Solomon, Voter Residency Requirements Strengthened in New Hampshire, Governing (July 18, 2018, 9:15 AM), https://www.governing.com/topics/politics/tns-new -hampshire-voting-residency.html [https://perma.cc/3KXD-FRJ6] (describing a requirement to have a vehicle registered in the state).

See, e.g., Matt Zdun, Chris Essig & Darla Cameron, Texas State Students Were Likely a Key Factor in Flipping This Conservative County to Democrats, Tex. Trib. (Nov. 15, 2018, 12:00 AM), https://www.texastribune.org/2018/11/15/texas-state-students-young-voters-hays-county [https://perma.cc/84KF-4WN3].

There are passing references to the lack of physical access to polling locations in some articles but nothing examining the issue as a particular obstacle to student participation. See, e.g., Elizabeth Aloi, Thirty-Five Years After the 26th Amendment and Still Disenfranchised: Current Controversies in Student Voting, 18 Nat’l Black L.J. 283, 288-89 (2004) (describing briefly the battle for a polling place at the Prairie View A&M campus in Texas); Eric S. Fish, The Twenty-Sixth Amendment Enforcement Power, 121 Yale L.J. 1168, 1181 (2012) (“Consider all the policies that may abridge the right to vote on the basis of age: locating polling places away from colleges, requiring registrants to have drivers’ licenses, splitting a college campus between two legislative districts, etc.”).

The Texas Civil Rights Project, as part of a coalition of community and legal organizations, helps operate the Election Protection program, with field volunteers and a toll-free hotline to assist voters encountering problems. See Election Protection, https://866ourvote.org [https://perma.cc/FQ3S-6HNN].

See, e.g., Erin Mansfield, Firm Hired to Redraw Election Precincts, Tyler Morning Telegraph (June 5, 2019), https://tylerpaper.com/firm-hired-to-redraw-election-precincts/article _04e1c418-75ef-5f36-ae7d-c83e165894a0.html [https://perma.cc/JT94-AFGE] (describing Smith County’s plans to use an outside firm to help redraw election precincts in 2021). Election precincts are the neighborhood-level districts into which local subdivisions, typically counties, divide voters to assign them to electoral districts (for example, congressional districts) and polling places.

See Dylan Lynch, All-Mail Elections (aka Vote-by-Mail), Nat’l Conf. St. Legislatures (June 27, 2019), http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/all-mail-elections.aspx [https://perma.cc/5BWG-HW5G]; Elections and Campaigns, Nat’l Conf. St. Legislatures, http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/vote-centers.aspx [https://perma.cc/ZW4R-CDYF].

See Emily Eby & Beth Stevens, Texas Election Protection 2018: How Election Administration Issues Impacted Hundreds of Thousands of Voters, Tex. Civ. Rts. Project 10 (Mar. 2019), https://texascivilrightsproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2019-Election-Protection-Report.pdf [https://perma.cc/42JC-H2Z6] (describing voter confusion and how, across Texas’s five largest counties, 4,608 provisional ballots were not counted because they were cast in the incorrect location). Poll workers are, in theory, encouraged to direct voters to their correct polling place. See Ashley Fischer, Election Day Procedures and Provisional Voting, Tex. Secretary St. 71 (Aug. 25, 2019), https://www.sos.texas.gov/elections/forms/seminar/2015/17th /election-day-procedures.ppsx [https://perma.cc/6ZE5-Z4P2]. However, they may fail to do so, or the voters simply may not have time or the will to travel to another polling place and potentially stand in a long line to cast their ballot.

Facts & Data, Tex. St. U., https://brand.txstate.edu/facts-and-data.html [https://perma.cc/MYJ7-568X] (stating figures as of fall 2018).

QuickFacts: Hays County, Texas, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/hayscountytexas [https://perma.cc/C68E-PGBP].

A paper street is a street that appears on a map but has not been physically constructed or no longer exists. See Paul G. Sanderson, Paper Streets: The Gap Between Dedication and Acceptance, N.H. Municipal Ass’n (Apr. 2007), nhmunicipal.org/town-city-article/paper-streets-gap -between-dedication-and-acceptance [https://perma.cc/GCT3-UYG2].

See Phil Prazan, Hays County Democrat Files Suit to Contest Commissioner Election, kxan (Dec. 14, 2018), https://www.kxan.com/news/local/hays/hays-county-democrat-files-suit-to-contest-commissioner-election/ []. Other specific reports were tracked through a proprietary system at TCPR.

Eby & Stevens, supra note 22; QuickFacts: Bexar County, Texas; Dallas County, Texas, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/bexarcountytexas ,dallascountytexas/PST045218 [https://perma.cc/N6A7-EAEG].

Precinct 332 is in Texas Congressional District 21, whereas Precinct 413 is in District 35, see PLANC235, DistrictViewer, https://dvr.capitol.texas.gov/Congress/2/PLANC235, and County Commissioner Precinct 3 as opposed to 4.

See Cumulative Report—Official—Hays County—General Election—November 6, 2018, Hays County 9, 11 (Nov. 13, 2018) https://hayscountytx.com/download/departments/elections /results/2018/11-06-2018-General-Election-Cumulative-official.pdf [https://perma.cc /YVK9-9QJY].

Enrollment Statistics, Prairie View A&M U. (2018), http://www.pvamu.edu/ir/wp-content /uploads/sites/98/Fall-2018.pdf [https://perma.cc/85X9-DRV8].

QuickFacts: Waller County, Texas, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts /fact/table/wallercountytexas/PST045218 [https://perma.cc/5Y6R-N87P].

See, e.g., Elizabeth Summers, One Texas School’s Long Walk of Political Engagement, PBS NewsHour (Nov. 5, 2012, 7:00 AM), https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/picture-this-more -than-1000 [https://perma.cc/Z3KU-JN3V]; see also Emily Foxhall, Waller County Backs Off Plan to Limit Early Voting, Houston Chron. (Jan. 5, 2016), https://www.houstonchronicle .com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/Waller-Co-backs-off-plan-to-limit-early-voting -6739007.php [https://perma.cc/Z6U8-HTSG]; Jasper Scherer, Democrats Demand Waller County Fix PVAMU Voter Registrations, Houston Chron. (Oct. 16, 2018), https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/Democrats-demand-Waller -County-fix-PVAMU-voter-13300986.php [https://perma.cc/F7NV-XM6N].

See Eric Holder, It’s Time for Americans to Take Back the Vote, Time (Oct. 18, 2018), https://time.com/5428175/take-back-the-vote [https://perma.cc/2UUN-93RE]; Ella Nilsen, North Carolina’s Extreme Gerrymandering Could Save the House Republican Majority, Vox (May 8, 2018, 11:00 AM) https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/5/8/17271766 /north-carolina-gerrymandering-2018-midterms-partisan-redistricting [https://perma.cc /5R6T-8T3H].

Ohio A. Philip Randolph Inst. v. Householder, 373 F. Supp. 3d 978, 1158 (S.D. Ohio 2019) (“In Hamilton County and on The Ohio State University’s campus in particular, the HCYD’s and OSU College Democrats’ representatives testified that they have seen campaign signs for certain candidates in the wrong district and that people have been mistaken as to which district they should be voting in.”).

Terra Rivers, Hays County Polling Places, Travis County Clerk’s Office Experience Technical Issues; Hays County Early Voting Totals Day 1, San Marcos Corridor News (Oct. 23, 2018), https://smcorridornews.com/hays-county-polling-places-travis-county-clerks-office -experience-technical-issues [https://perma.cc/7ZP5-GCXH]; Terra Rivers, Day 2 Of Hays County Early Voting Turnout, San Marcos Corridor News (Oct. 24, 2018), https:// smcorridornews.com/day-2-of-hays-county-early-voting-turnout [https://perma.cc/Y8B6 -C3QG]; 3 Days of Early Voting, Mail-In Ballot Totals, San Marcos Corridor News (Oct. 25, 2018), https://smcorridornews.com/3-days-of-early-voting-mail-in-ballot-totals [https:// perma.cc/PCD7-KLQM].

Office of Institutional Research, University Enrollment, Tex. St. U., https://www .ir.txstate.edu/reports-projects/highlights/highlights-enrollment [https://perma.cc/4X25 -JLPW].

Courtney Clevenger, UTSA Enrolls Record Number of Students, Boosts Graduation Rates Three Percent, According to New Data, U. Tex. San Antonio (Sept. 28, 2018), https://www.utsa.edu/today/2018/09/story/Fall2018CensusandGradRates.html [https:// perma.cc/CXW5-HH7M].

Facts & Figures, U. Tex. Austin (2019) https://www.utexas.edu/about/facts-and-figures [https://perma.cc/2UCC-BFS6].

Alexa Ura, Student Voting Rights Fight Erupts at Texas State University, Tex. Trib. (Oct. 25, 2018), https://www.texastribune.org/2018/10/25/student-voting-rights-fight-erupts-texas -state-university [https://perma.cc/X8QR-PGWN]; Letter from Beth Stevens, Voting Rights Legal Director, to Bert Cobb, Hays County Judge, and Jennifer Anderson, Hays County Election Administrator (Oct. 25, 2018), https://texascivilrightsproject.org/wp -content/uploads/2018/10/Letter-to-Hays-County-10.25.18-1.pdf [https://perma.cc/8DH5 -444T].

Becky Fogel, News Roundup: Early Voting Will Resume at Texas State University, Tex. Standard (Oct. 29, 2018), https://www.texasstandard.org/stories/news-roundup-early-voting -will-resume-at-texas-state-university [https://perma.cc/SBW8-S7D7].

Day 11 of Hays County Early Voting Turnout, San Marcos Corridor News (Nov. 2, 2018), http://smcorridornews.com/day-11-of-hays-county-early-voting-turnout [https://perma.cc /2B46-JMLJ].

Matt Zdun, Waller County Expands Early Voting for Prairie View A&M Students, Tex. Trib. (Oct. 25, 2018), https://www.texastribune.org/2018/10/25/waller-county-expands-early -voting-prairie-view-m-students [https://perma.cc/5TL3-KTJ7].

North Carolina State University, Rankings, NCSU, https://www.ncsu.edu/about/rankings [https://perma.cc/6CBD-LF7W].

Editorial, We Should Be Able to Vote on Campus, Technician (Oct. 22, 2014), http://www .technicianonline.com/opinion/article.html [https://perma.cc/G3YN-3UJ3].

Evan Walker-Wells, Blocking the Youth Vote in the South, Facing South (Oct. 29, 2014), https://www.facingsouth.org/2014/10/blocking-the-youth-vote-in-the-south.html [https://perma.cc/BRJ5-4HL6].

League of Women Voters of Fla., Inc., v. Detzner, 314 F. Supp. 3d 1205, 1223 (N.D. Fla. 2018). The Twenty-Sixth Amendment holds that “[t]he right of citizens of the United States, who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of age.” U.S. Const. amend. XXVI.

See, e.g., Travis County Mobile Voting Locations, Travis County, Tex., https://www. traviscountytx.gov/images/county-clerk/docs/pdf_tc_elections_2018.11.06_g18_mobile _flyer_v2.pdf [https://perma.cc/UD7W-TSQ7].

This is something with which some jurisdictions have experimented. See, e.g., Frankie Barnhill, How “Food Truck Voting” Is Catching on in One Idaho County, NPR (Oct. 29, 2016), https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/10/29/499856446/how-food-truck-voting-is -catching-on-in-one-idaho-county [https://perma.cc/KK67-6CX3].

See Sunny Frothingham, Greater Costs, Fewer Options: The Impact of the Early Voting Uniform Hours Requirement in the 2018 Election, Democracy N.C., https://democracync.org/research /greater-costs-fewer-options-the-impact-of-the-early-voting-uniform-hours-requirement -in-the-2018-election [https://perma.cc/J93D-Y3WE].

Id. (“The turnout rate for North Carolina’s youngest voters jumped 11% statewide, but each additional mile between voters and Early Voting sites shrank that surge in youth voting by more than a percentage point. For instance, in Bertie County, where the distance between voters and Early Voting sites increased by an average of 5.6 miles, youth turnout increased by 3.5 percentage points compared to 2014—paling in comparison to the statewide 11 percentage point jump.”).

Jo Clifton, ‘Death of Mobile Voting’ Bill to Complicate Elections, Austin Monitor (May 29, 2019), https://www.austinmonitor.com/stories/2019/05/death-of-mobile-voting-bill-to -complicate-elections [https://perma.cc/C6C4-TQDV].

See Texas H. Journal at 3109-3124 (May 7, 2019), https://journals.house.texas.gov /hjrnl/86r/pdf/86RDAY60FINAL.PDF [https://perma.cc/5XE9-LV3U] (rejecting the aforementioned amendments).

See Bud Kennedy, 11,000 College Votes Turned Tarrant County Purple in 2018. Now Campus Voting May End, Fort Worth Star Telegram (Sept. 28, 2019), https://www.star-telegram .com/news/politics-government/article235524697.html [https://perma.cc/HCH4-8AN9].

Alexa Ura, Judge Orders Harris County to Keep Some Polling Locations Open an Extra Hour, Tex. Trib. (Nov. 6, 2018), https://www.texastribune.org/2018/11/06/election-day-texas -midterms-delays-technicals-difficulties [https://perma.cc/7T2W-THR3].

Ronald Brownstein, Brace for a Voter-Turnout Tsunami, Atlantic (June 13, 2019), https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2019/06/2020-election-voter-turnout-could -be-record-breaking/591607 [https://perma.cc/5RGD-PGEL].

Judicial Selection: An Interactive Map, Brennan Ctr. for Just., http:// judicialselectionmap.brennancenter.org [https://perma.cc/K58F-RBFQ].

Joanna Shepherd & Michael S. Kang, Partisan Justice: How Campaign Money Politicizes Judicial Decisionmaking in Election Cases, Am. Const. Soc’y (2016), https://www.acslaw.org/analysis /reports/partisan-justice [https://perma.cc/KJ5L-CK5X]; see Andrew Blotky & Billy Corriher, State and Federal Courts: The Last Stand in Voting Rights, Ctr. for Am. Progress 5-7 (June 25, 2013), https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06 /CorriherVotingRights1.pdf [https://perma.cc/2FKC-TWAT].

See, e.g., Ariz. Democratic Party v. Reagan, No. CV-16-03618-PHX-SPL, 2016 WL 6523427, at *17 (D. Ariz. Nov. 3, 2016) (“The Committees did not file their complaint in this action until more than a week after the voter registration deadline had passed, and only a few weeks before the general election is to take place. This delay was unreasonable.”).

See, e.g., Lucas Cty. Democratic Party v. Blackwell, 341 F. Supp. 2d 861, 864-65 (N.D. Ohio 2004) (“Moreover, it would be entirely improper, and substantially disruptive of the election process and its orderly administration for me to order Ohio’s County Boards to re-open in-person registration from now until Election Day. Doing so would require me to override the requirement of Ohio’s election law that an individual be registered to vote for thirty days before an election.”).

Chase Rogers, Hays County Commissioners Court to Keep Texas State Polling Location Following Outcry, U. Star (Sept. 3, 2019), https://universitystar.com/31116/news/hays-county -commissioners-court-to-keep-texas-state-polling-location-following-outcry [https:// perma.cc/S695-BBL4].

Miles Parks, Ahead of 2020 Election, Voting Rights Becomes a Key Issue for Democrats, NPR (Feb. 8, 2019, 5:00 AM ET), https://www.npr.org/2019/02/08/692370775/ahead-of-2020-election -voting-rights-becomes-a-key-issue-for-democrats [https://perma.cc/DFD3-J6LW].

Chiraag Bains, Texas Tried to Mess with Voting. It Failed., Am. Prospect (June 11, 2019), https://prospect.org/article/texas-tried-mess-voting-it-failed [https://perma.cc/9AZA -8JR2].

Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick Announces 30 Priority Bills for 2019 Legislative Session, Lieutenant Governor Tex. (Mar. 8, 2019), https://www.ltgov.state.tx.us/2019/03/08/lt-gov-dan-patrick -announces-30-priority-bills-for-2019-legislative-session [https://perma.cc/B8K9-DR6P].