Ending Citizenship for Service in the Forever Wars

abstract. Citizenship for service is a historic tradition in the United States dating back to the Revolutionary War in which noncitizens, through military service, earned citizenship and were able to naturalize. This Essay briefly describes the history of citizenship for service dating back to the Revolutionary War and argues that two recently enacted Department of Defense policies are erecting obstacles to, and effectively ending, this centuries-old pathway to citizenship. The Essay presents data from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service demonstrating that the number of military naturalizations and military naturalization applications has plummeted since the two policies took effect. Further, it reflects on how these new restrictions may show that our polity is redefining what it means to be a U.S. citizen in a way that ultimately cheapens citizenship and weakens the nation.

Introduction

Despite the increased importance of formal citizenship in our current era, one historic pathway for noncitizens to join the polity by naturalization is quickly, and quietly, disappearing.1 Citizenship for service, a centuries-old concept allowing military service to lead to naturalization, has recently faced several obstacles—obstacles that appear to be only the first of many. New regulations promulgated by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Defense (DOD) make the statutory method of gaining citizenship for service, as codified in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), a near impossibility. More recent policies dating back to the beginning of the “War on Terror,” which granted a pathway to citizenship to those with no alternative ways to naturalize, have also been suspended or repealed. While tightening restrictions on immigration are by no means a new development, it is perhaps surprising that this particular pathway to citizenship is being curtailed in the context of the longest period of hostilities in U.S. history—a period that some have dubbed the “Forever Wars.”2

The new restrictions on military naturalizations are significant. Citizenship as a concept and as a legal reality has taken on new urgency in the lives of millions of immigrants.3 In a climate of fear—amid strict enforcement initiatives, decreased legal protections, and increasing social exclusion of immigrants—the protections of formal citizenship are ever more relevant. Once granted, formal citizenship offers numerous tangible benefits: protections from physical exclusion and exile, access to a larger social safety net, the ability to participate more fully in politics, and immediate relative sponsorship for immigrant visas. Moreover, citizenship offers the intangible, symbolic benefit of joining the polity—a political society linked by the single identity of “American.” Although the benefits of formal citizenship are great, citizenship comes also with duties to the country and to fellow citizens. Some of these duties—military service above all—impose heavy burdens that current U.S. citizens appear increasingly unwilling to bear themselves. The restrictions on military naturalizations for noncitizens who are willing to shoulder the heaviest of these burdens reflect a broader failure to appreciate the duties of citizenship in a way that ultimately weakens the nation and cheapens citizenship itself.

Part I of this Essay recounts the history of citizenship for service as it dates back to the Revolutionary War. Part II briefly explains modern immigration law as it relates to military naturalizations. Part III details some recent policy changes by DOD and DHS that have erected barriers to this historic pathway to citizenship. Part IV uses data from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to demonstrate the effect these policies have had on military naturalizations. Part V concludes with a reflection on what these changes may mean for the security of the nation and for U.S. citizenship—including how these changes reflect a changing definition of what it means to “be an American.”

I. history of citizenship for service

From the earliest days of the republic, periods of hostility have created a need for military manpower. That need has led the U.S. government to offer noncitizens, in exchange for their service, a pathway to joining the polity as full citizens.4

During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress and the early states initially filled their military ranks in the traditional way: by paying their soldiers. But as the war dragged on, coffers and recruits depleted, forcing some states to use noncitizen recruits in their armies with the promise of full citizenship at the end of the war.5 The Civil War was no different, and when the first national draft law was created, foreign nationals who had declared an intent to naturalize were able to gain citizenship through military service.6 In exchange for their service, these immigrant soldiers enjoyed the first codified expedited naturalization process.7

The World Wars saw the greatest number of military naturalizations, with a total of 244,300 individuals naturalized through military service from 1918 to 1920; and 109,392 from 1943 to 1945.8 Indeed, during the Second World War, in order to boost troop numbers in the Pacific, President Roosevelt conscripted the army of the Philippines in return for the full benefits that would come with military service in the U.S. Army, including the apparent promise of citizenship.9

More recent wars have been no different, with spikes in military naturalizations during periods of hostility. The War on Terror, however, has been unique in one important respect: it is the longest-running “period of hostility” in U.S. history.10 There does not appear to be an end in sight, and throughout the conflict, noncitizens have been an integral segment of the U.S. Armed Forces. Indeed, it is reported that 35,000 noncitizens currently serve as active-duty members of the Armed Forces, and that 8,000 more enlist each year.11 Certain programs, such as the controversial Military Accessions Vital to National Interest (MAVNI) program, have allowed those who do not have legal status, including foreign nationals qualifying for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), to serve in the military during these “forever wars,” effectively granting a pathway to citizenship to those who would otherwise have none.12 Under President Obama in 2016, this program was effectively suspended indefinitely.13 Beyond the national security risks cited as the reason for the program’s ultimate suspension, one major criticism of the program was that those naturalized through MAVNI were subject to biannual security check-ins—a process that essentially created a second class of citizens until it was enjoined as unlawfully discriminatory in early 2019.14 For a time though, MAVNI offered one of the very few ways “Dreamers” could escape their undocumented status and signaled that those willing to bear the heaviest burden of citizenship deserved to join the polity, regardless of formal immigration status.

II. modern military naturalization

Under the INA,15 there are two routes that expedite the naturalization process for noncitizens serving in the military—one for peacetime (§ 328) and one for periods of hostility (§ 329). The peacetime provision, which has not been in effect since the United States entered the current period of hostilities on September 11, 2001, is best understood as a simple fast track to naturalization. Rather than the traditional requirements mandating five years of lawful permanent-resident status, a noncitizen need only have served in the Armed Forces for one year and have resided in the United States for five years.16

The provision for periods of hostility provides even greater expediency and laxer requirements.17 Individuals need not have lawful status, so long as they were present in the United States when they enlisted. There is no continuous-residence or physical-presence requirement. In theory then, a noncitizen soldier could naturalize immediately after completing basic training. Additionally, the requirement of demonstrating good moral character shrinks from five years to one.18 So long as an individual can demonstrate honorable service, naturalization through military service during hostilities faces few statutory hurdles.

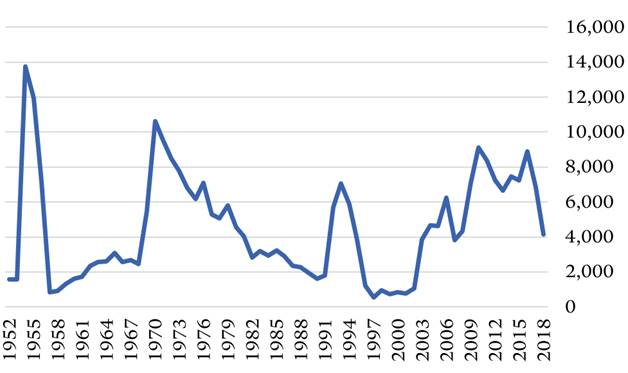

figure 1. military naturalizations (1952-2018)19

|

Since the enactment of the INA, President-designated periods of hostility have included the Korean Conflict from June 25, 1950 to July 1, 1955; the Vietnam Hostilities from February 28, 1961 to October 15, 1978; the Persian Gulf Conflict from August 2, 1990 to April 11, 1991; and the War on Terror from September 11, 2001 to the present.20 Spikes in military naturalizations occur, as expected, during each of these periods of hostilities. Corresponding drop-offs in military naturalizations often follow once hostilities have ended. However, there is a sharp drop from approximately 7,000 naturalizations in 2017 to approximately 4,000 in 2018, even though the present period of hostilities is ongoing.21 While there is not yet enough data to identify a long-term trend, newly enacted policies suggest that future military naturalizations, even within the current period of hostilities, will decline further.

III. recent policy changes

The decline of citizenship for service is likely the result of a multitude of recently enacted policies that have either erected obstacles to the historic pathway to citizenship laid out in the INA or halted the ability of certain individuals to start down that path altogether. Locations where service members may be naturalized have been reduced from twenty-three to four;22 the MAVNI programis no longer in use;23 and the Basic Training Naturalization Initiative, which would, true to its name, allow noncitizen enlistees to naturalize as soon as they completed basic training, has been terminated.24 In addition to these policies, two policy memoranda issued by DOD in late 2017 appear to be limiting military naturalizations by erecting two new and substantial hurdles to citizenship for service that are not required by either statute or regulation.

The first policy change is on its surface a simple procedural change. But in effect it renders naturalization impossible for the vast majority of new recruits. On October 13, 2017, DOD issued a policy memorandum changing the required manner in which noncitizens serving in the Armed Forces obtain the necessary Form N-426 Request for Certification of Military or Naval Service.25 This form is the means through which an individual demonstrates to USCIS that he or she is serving or has served honorably in the Armed Forces, as required for military naturalization.26

The policy memorandum changed the number of days an individual must be in active service before a Form N-426 can be issued from zero to 180, or to an entire year if serving in the Army Reserves, creating a delay that is not required by statute.27 Further, the memorandum raised the minimum rank of the officer who is signing the document. Whereas prior to the memorandum the Form N-426 could be signed by an applicant’s commanding officer, the new policy memorandum places original authority to sign these forms with the Secretary of the military department in which the individual serves. The Secretary can delegate this authority, but only to someone at or above an O-6 rank commissioned officer,28 which translates to a Colonel if in the Army, Marine Corps, or Air Force; and to a Captain if in the Navy or Coast Guard.29

Not only must the form be completed by such a high-ranking officer, but the form submitted to USCIS must be the original.30 No scans or copies will be accepted. Notably absent from this policy guidance, and still absent two years later, are procedures that applicants can follow to have their forms signed by a Colonel or Captain and returned to them. While some military bases have created the position of “naturalization representative” to help guide noncitizens through the process, outreach by these representatives has been minimal, and education about the process throughout the military has been negligible.31

The rationale given by DOD is facially reasonable—one needs a certificate of honorable service in order to naturalize, and how can a superior officer attest to that after only a few days of training?32 However, not only does this explanation ignore the fact that a military service member will lose her citizenship should she fail to serve honorably for at least five years, but more importantly, it fails to mention one of the greatest incentives for the military to naturalize service members—the ability for those members to work in positions that require high-level security clearance.33 The given explanation is inadequate when recruitment numbers are down, the MAVNI program is inoperative, and the concerns raised are addressed by explicit statutory safeguards.

In practice, this policy requires an individual either to have some personal connection with one of the highest-ranking individuals in the Armed Forces or to submit their form through the chain of command in the hopes that it will reach an appropriate officer who will complete it properly and submit the original back to them—all while being subject to additional delays of 180 days or more before the entire process may even begin. As one expert in military naturalization law stated in testimony to the Immigration and Citizenship Subcommittee, “[n]ow we have chaos.”34 The process has become so cumbersome and prolonged that naturalizing as a civilian is considered the faster and safer alternative—entirely contrary to congressional intent in creating an expedited pathway to citizenship for members of the Armed Forces.35

On the day that DOD issued the N-426 policy memorandum, it also issued a second memorandum requiring heightened security screenings and background checks for noncitizens who wish to enter the military, including permanent residents. Whereas previously noncitizens could enter basic training so long as their background checks were underway, they must now wait to receive a favorable “Military Service Suitability Determination” before they may begin.36 When this policy was first implemented, backlogs made the wait for the first issuance of such a security clearance, stretch up to a year.37

These new security-clearance policies have not only delayed the entry of noncitizens to the military, but they also meant for a time that an entire branch of the military—the Army Reserve—refused to recruit permanent residents.38 While the mantra of this new tightening of requirements for noncitizen military naturalizations has been “national security,” it is unclear to practitioners and scholars whether the policy is justified or simply pretextual—after all, lawful permanent residents undergo stringent background checks before they are even issued a green card.39 It is also unclear whether the new background screens have prevented any more security risks than the previous policy had. What is clear is that the policy adds further delay to any individual attempting to naturalize through the military.

The combined effect of these policies is two new, significant delays for any noncitizen attempting to naturalize through the military. Neither is required by statute, and neither seems necessary.

IV. results of recent policies

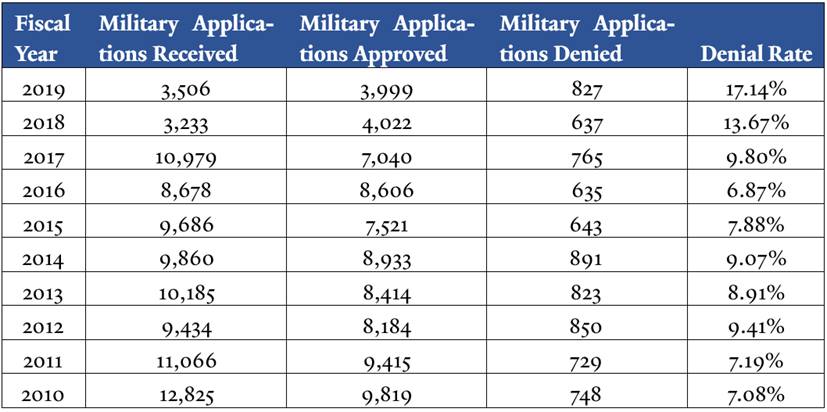

It has not been long since these policies have been implemented, but the data already show large decreases in the number of applications received by USCIS for military naturalization, as well as a spike in denial rates. USCIS has published data that show military applications received, approved, and denied from fiscal years 2010 to 2019, with data prior to 2010 showing only the numbers approved.40 However, the data for the past ten years still give insight into recent trends, as illustrated in Table 1.

table 1. military naturalization applications received, approved, and denied (2010-2019)41

|

One notable observation from these data is the large decrease in military applications received—the average from 2010 to 2017 was 10,339, compared to only 3,233 in 2018. Denial rates also appear to be rising—the average from 2010 to 2017 was 8.28%, compared to 13.67% in 2018 and 17.14% in 2019.

Some may argue that these shifts in military naturalization numbers can be accounted for by forces beyond the recently implemented policies. For example, naturalization applications historically increase in the year leading up to a presidential election, then drop off.42 The conflicts in the Middle East are increasingly unpopular, and plans to withdraw the United States from the various conflicts date back to the presidency of George W. Bush.43 This may push certain applicants away from military service, or motivate noncitizen soldiers to leave the service before applying for citizenship. It is also unclear how aware military personnel are of the naturalization procedures. As seen by the widely reported “deported veterans,” many military service members assume or are told that they have already become citizens upon enlistment.44 Given recent changes to the naturalization process, military personnel may not understand the new procedures, leading to fewer applications.

However, looking at quarterly rather than yearly data helps isolate the effects of recent policy changes. In the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2017, covering July through September, and prior to the October 2017 implementation of the new DOD memoranda discussed above, USCIS received 3,132 applications for military naturalization.45 Of those it adjudicated, USCIS approved 2,123 and denied 214, or 9.2%.46 In the subsequent quarter, following the implementation of the memoranda, USCIS received only 1,069 applications for military naturalization.47 It approved 755 and denied 191, or 20.2%.48 These numbers did not recover after the first anomalous quarter, with subsequent quarters still showing a noticeable drop in the number of applications received and a higher denial rate relative to pre-memoranda numbers.49

In sum, while there may be other factors at play in the reduction of application numbers and the rising denial rate, the 2017 policy memoranda likely play a central role. These hurdles to military naturalization are still new, and many of their effects have yet to be felt. Nonetheless, it is crucial to understand their numeric and conceptual implications, especially in the context of complementary policies that are actively chipping away at the link between military service and citizenship.50

V. implications for the meaning of citizenship

Military service is a uniquely burdensome pathway to citizenship that emphasizes the duties of citizenship over the benefits. To start down the historic pathway of citizenship for service, individuals must be willing to set aside their own lives in service of a country that has not yet accepted them as full members. For noncitizens on this path, citizenship consists of robust duties and commitments that the rest of the polity increasingly seems not to appreciate.

The duties of citizenship have come to play a peripheral role in the contemporary practice of citizenship. When it comes to the duty of voting in elections, for instance, voter turnout since the early 1900s has peaked at approximately 60% of the eligible population.51 Jury duty is another oft-cited duty of citizenship, yet only approximately 67% of U.S. adults see it as part of good citizenship.52 Indeed, although trial by jury is enshrined in the Constitution, jury trials are increasingly rare, giving citizens less opportunity to participate in the judicial process.53 USCIS lists as a duty of citizens that they must “respect and obey federal, state, and local laws,”54 yet nearly one in three Americans has some sort of criminal record.55 Finally, a uniquely burdensome duty of citizenship is to defend one’s country in times of hostility, but the percentage of the population with military experience was only 8% in 2014, down from 18% in 1980.56

For the country to function as designed, someone must bear the burdens and fulfill the duties of citizenship. One would therefore expect a pathway to citizenship that emphasizes duty to country and to the citizenry as a whole to be celebrated and protected by the polity. Instead, however, this pathway has become increasingly narrow. These restrictions may be the result of anti-immigrant sentiments in the age of President Obama, called the “Deporter-in-Chief,” and President Trump, whose draconian enforcement initiatives are widely reported.57 Allowing anti-immigrant sentiments to restrict citizenship for service contributes to the hollowing out of our understanding and practice of citizenship. And it also compounds the practical problems of insufficient military recruits and unfilled high-level military positions. Even though national security is touted as the reason behind the new restrictions, the restrictions instead diminish national security. We, who are already members of the polity, bear ultimate responsibility for these changes and will shoulder their consequences.

Conclusion

Citizenship for service has been a central part of our nation’s history since its founding. Yet that institution is rapidly eroding today. Restrictions on citizenship for service through two 2017 DOD policy memoranda have already led to decreased naturalization numbers. Subsequent policies are likely to accelerate this trend.

Citizenship for service rewards those willing to sacrifice everything for their chosen country with the benefits of full citizenship. It supports our nation by incentivizing individuals to serve in the military, and by providing manpower when recruitment of citizens is insufficient. Furthermore, it strengthens the meaning of citizenship by offering membership to those who bear its heaviest burdens. By restricting the naturalization of those who are willing to carry the weightiest duties of citizenship, especially during its longest period of hostilities, the United States is redefining itself in a way that weakens what it means to be an American.

Zachary R. New is a graduate of the University of Colorado School of Law and an associate attorney at the Denver office of Joseph & Hall, P.C., where he focuses on corporate immigration and federal litigation of immigration claims. A special thank you to Yale Law Journal editors Lawrence J. Liu and Zach Lustbader for their thoughtful comments and contributions that elevated and refined this paper.

This Essay uses the terms “foreign national” and “noncitizen” interchangeably, and in place of the term “alien,” to mean an individual born outside of the United States who does not possess formal U.S. citizenship. To be eligible for U.S. military service, one must have some form of lawful status, so the legal intricacies that surround the term “noncitizen” are largely inapplicable. A U.S. national would, for example, be counted within the term “noncitizen,” as such an individual is eligible for U.S. citizenship through military naturalizations in the same way in which a foreign national with a lawful status would be. Further, the statutory term “alien” has developed offensive connotations. “Lawful permanent resident” or permanent resident refers to foreign nationals who have immigrated on a permanent basis to the United States and received what is referred to as their “green card.”

See Jennifer Steinhauer, Two Veterans Groups, Left and Right, Join Forces Against the Forever Wars, N.Y. Times (Mar. 16, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/16/us/politics/vote -vets-concerned-veterans-america.html [https://perma.cc/FB3A-XWJV].

In the late 2000s, some scholars argued that formal citizenship was becoming increasingly anachronistic and little more than a formality. See, e.g., Peter J. Spiro, Beyond Citizenship: American Identity After Globalization (2008). However, a new wave of nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiment in the last decade casts serious doubts on this view.

Table 20. Petitions for Naturalized Filed, Persons Naturalized, and Petitions for Naturalization Denied: Fiscal Years 1907 to 2017, U.S. Dep’t Homeland Security (Oct. 2, 2018), https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook/2017/table20 [https://perma.cc /B47W-955T].

Military Order: Organized Military Forces of the Government of the Commonwealth of the Philippines Called into Service of the Armed Forces of the United States, 6 Fed. Reg. 3825 (Aug. 1, 1941). Over 250,000 Filipinos fought as guerillas, scouts, or enlisted men in the Pacific theater under orders of the U.S. military, expecting the full benefits of joining the United States military, including U.S. citizenship, in exchange. In the end, this promise was left unfulfilled, and Filipino WWII veterans are, to this day, still fighting for the full benefits promised to them. See Dorian Merina, Their Last Fight: Filipino Veterans Make a Final Push for Recognition, Am. Homefront Project (July 30, 2018), https://americanhomefront .wunc.org/post/their-last-fight-filipino-veterans-make-final-push-recognition [https:// perma.cc/9HF5-M2LP].

See 12 U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Servs., Policy Manual ch. 3 (2019), https:// http://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-12-part-i-chapter-3 [https://perma.cc/MQ7H -GEAR].

See The U.S. Military Helps Naturalize Non-Citizens, Military (2019), https://www .military.com/join-armed-forces/eligibility-requirements/the-us-military-helps-naturlize -non-citizens.html [https://perma.cc/WW37-WR3T].

Military Accessions Vital to National Interest (MAVNI) Program Eligibility, U.S. Dep’t Def. (Nov. 1, 2014), https://www.aila.org/infonet/dod-fact-sheet-on-mavni-program-eligibility https://dod.defense.gov/news/mavni-fact-sheet.pdf [https://perma.cc/ G96E-5TKW]. This program was established in 2008 under President Bush to create a specialized pathway for noncitizens with special skills (including language and medical skills, which were in short supply in the military) to join the Armed Forces and thus have a pathway to naturalization. Due to alleged security risks, including reported use of false identities to attempt to join the MAVNI program, the program was suspended. See infra note 13.

In 2016, the Obama Administration created additional background-screening requirements for MAVNI recruits, which effectively ended the program. Indeed, one of the foremost experts on military naturalizations, Margaret Stock, has stated that no new MAVNI recruits have joined the Armed Services since the changes. See Tara Copp, Here’s the Bottom Line on the Future of MAVNI: Many Foreign-Born Recruits May Soon Be Out, Mil. Times (July 6, 2018), https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2018/07/06/heres-the-bottom-line -on-the-future-of-mavni-many-foreign-born-recruits-may-soon-be-out [https://perma.cc /H9R6-FXT6].

Figure 1 displays data from 1952 to 2018 to correspond with the time that the INA has been in effect and because the numbers of military naturalizations in World War I and World War II are “off the charts.” The data used in the table are from Military Naturalization Statistics, U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs. (Dec. 6, 2018), https://www.uscis.gov/military/military -naturalization-statistics [https://perma.cc/4KZK-PB28].

Richard Sisk, The Naturalization Process Just Got Harder for Noncitizen Troops Stationed Overseas, Military (Sept. 30, 2019), https://www.military.com/daily-news/2019/09/30 /naturalization-process-just-got-harder-noncitizen-troops-stationed-overseas.html [https://perma.cc/NQK4-DS8L].

See The Impact of Current Immigration Policies on Service Members and Veterans, and Their Families: Hearing Before H. Subcomm. on Immigration & Citizenship, 116th Cong. at 1:20:52 (2019) [hereinafter Immigration and Service Hearings] (statement of Margaret Stock, Attorney, Cascadia Cross Border Law Group LLC) (describing the termination of basic training nationalization). Interestingly, these policy changes come at a time when military recruitment is becoming increasingly difficult: the U.S. Armed Forces failed to meet recruitment goals in 2018 for the first time since 2005Matthew Cox, Army Scaling Back Recruiting Goals After Missing Target, Under Secretary Says, Military (Mar. 21, 2019), https://www.military.com/daily-news/2019/03/21/army-scaling-back-recruiting-goals-after-missing-target-under-secretary-says.html [https://perma.cc/KT5B-UXC3]; Cory Dickstein, Army Misses 2018 Recruiting Goal, Which Hasn’t Happened Since 2005, Stars & Stripes (Sept. 21, 2018), https://www.stripes.com/news/army/army-misses-2018-recruiting-goal-which-hasn-t -happened-since-2005-1.548580 [https://perma.cc/3DBS-ZGYT].

See Memorandum from A. M. Kurta, Acting Under Sec’y of Def. for Pers. & Readiness, U.S. Dep’t of Def., to Sec’ys of the Military Dep’ts & Commandant of the Coast Guard (Oct. 13, 2017) [hereinafter N-426 Memo], https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs /Naturalization-Honorable-Service-Certification.pdf [https://perma.cc/NKD8-SUYT].

See N-426, Request for Certification of Military or Naval Service, U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs. (July 10, 2019), https://www.uscis.gov/n-426. This form is required to be submitted with any military naturalization application in order to certify to USCIS that the applicant served honorably in the Armed Forces.

See U.S. Military Rank Insignia, U.S. Dep’t Def., https://www.defense.gov/Our-Story /Insignias/#enlisted-insignias [https://perma.cc/36LE-A6JR].

Immigration and Service Hearings, supra note 24, at 6 (written testimony of Jennie Pasquarella, Director of Immigrants’ Rights and Senior Staff Attorney, American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California) (“Many deported veterans we interviewed never applied for naturalization during their service because they were led to believe that their service automatically made them citizens. In fact, many had been told just that by their recruiters or their military chain of command . . . .”).

See Jim Garamone, DoD Announces Policies Affecting Foreign Nationals Entering Military, U.S. Dep’t Def. (Oct. 13, 2017), https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/News/Article/Article /1342430/dod-announces-policies-affecting-foreign-nationals-entering-military [https:// perma.cc/2KWF-XR72].

See 8 U.S.C. § 1440(c) (2018); How to Get a Security Clearance, Military (2019), https://www.military.com/veteran-jobs/security-clearance-jobs/official-security-clearance -guidelines.html [https://perma.cc/A9Q8-VPJV].

See Practice Advisory: Changes to the Expedited Naturalization Process for Military Service Members, Immigrant Legal Resource Ctr. (Mar. 2018), https://www.ilrc.org/sites/default /files/resources/changes_expedited_natz_process_military-20180329.pdf [https://perma .cc/MT7G-3KGF].

Memorandum from A. M. Kurta, Acting Under Sec’y of Def. for Pers. & Readiness, U.S. Dep’t of Def., to Sec’ys of the Military Dep’ts et al. (Oct. 13, 2017), https://dod.defense.gov/Portals /1/Documents/pubs/Service-Suitability-Determinations-For-Foreign-Nationals.pdf [https://perma.cc/VR7N-JKFF].

Meghann Myers, Green Card Holders Can Join the Army Reserve Again—After a Wait, ArmyTimes (Dec. 27, 2017), https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2017/12/27 /green-card-holders-can-join-the-army-reserve-again-after-a-wait [https://perma.cc/T8EK -2P6N]; Emily C. Singer, Green Card Holders Cannot Enlist in the Army Reserve “for the Time Being,” Army Confirms, Mic (Oct. 18, 2017), https://www.mic.com/articles/185357/green -card-holders-cannot-enlist-in-the-army-reserve-for-the-time-being-army-confirms [https://perma.cc/JX7D-2YBE].

As part of the application process for permanent residence, an individual’s information is queried through the Interagency Border Inspection System (IBIS), which collects data from multiple agencies, including the sub-agencies within the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, to identify any national security risks and prevent ineligible applicants from obtaining green cards. See U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Servs., Adjudicator’s Field Manual ch. 10.3, https://www.uscis.gov/ilink/docView/AFM/HTML /AFM/0-0-0-1/0-0-0-1067/0-0-0-1166.html [https://perma.cc/F82U-T8N4].

See Immigration and Citizenship Data, U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., https:// http://www.uscis.gov/tools/reports-studies/immigration-forms-data [https://perma.cc/8BAY-NXL7].

See Katherine Witsman, Annual Flow Report, U.S. Naturalizations: 2016, U.S. Dep’t Homeland Security (Nov. 2017), https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications /Naturalizations_2016.pdf [https://perma.cc/7AWG-76BZ].

R. Chuck Mason, Cong. Research Serv., R40011, U.S.-Iraq Withdrawal/Status of Forces Agreement: Issues for Congressional Oversight (2009), https://fas.org /sgp/crs/natsec/R40011.pdf [https://perma.cc/DX7Z-FZBC].

A large, and growing controversy surrounds the so-called “deported veterans.” The term refers to noncitizens who have served in the Armed Forces but did not naturalize, and then committed a removable offense after returning to civilian life that resulted in deportation. Many of these individuals report that they thought they already were citizens, leading to the widespread criticism that there is insufficient education for noncitizen service members on how to naturalize. See, e.g., Maria Ines Zamudio, Deported U.S. Veterans Feel Abandoned By the Country They Defended, NPR (June 21, 2019) https://www.npr.org/local/309/2019/06/21 /733371297/deported-u-s-veterans-feel-abandoned-by-the-country-they-defended [https:// perma.cc/ZMS7-RRBP] (“Velsaco said he was told by military personnel that he was a U.S. citizen. That was a lie.”).

Number of Form N-400 Applications for Naturalization, by Category of Naturalization, Case Status, and USCIS Field Office Location July 1-September 30, 2017, U.S Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Resources/Reports%20and%20Studies /Immigration%20Forms%20Data/Naturalization%20Data/N400_performancedata_fy2017 _qtr4.pdf [https://perma.cc/77M2-DU7W].

Number of Form N-400 Applications for Naturalization by Category of Naturalization, Case Status, and USCIS Field Office Location October 1-December 31, 2017, U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Resources/Reports%20and %20Studies/Immigration%20Forms%20Data/Naturalization%20Data/N400 _performancedata_fy2018_qtr1.pdf [https://perma.cc/SM59-QEGZ].

In the second quarter of Fiscal Year 2018, USCIS received only 661 applications for military naturalization, approved 420 applications, and denied 76, or 15.3%. Number of Form N-400, Application for Naturalization, by Category of Naturalization, Case Status, and USCIS Field Office Location January 1-March 31, 2018, U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., https://www .uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Resources/Reports%20and%20Studies/Immigration %20Forms%20Data/Naturalization%20Data/N400_performancedata_fy2018_qtr2.pdf [https://perma.cc/R8NW-5838]. It is also noteworthy that the Basic Training Naturalization Initiative was terminated at the beginning of the second quarter of Fiscal Year 2018. While this may partially explain later application numbers and denial rates, it cannot explain the sharp drop in the immediately preceding quarter.

This drop in quarterly numbers has persisted. In the fourth quarter of Fiscal Year 2019, USCIS received only 705 applications for military naturalization, approved 1,053 applications, and denied 175, or 14.25%. Number of Form N-400 Applications for Naturalization, by Category of Naturalization, Case Status, and USCIS Field Office Location July 1 1-September 30, 2019, U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Resources /Reports%20and%20Studies/Immigration%20Forms%20Data/Naturalization%20Data /N400_performancedata_fy2019_qtr4.pdf [https://perma.cc/9763-V4YL].

Further policies restricting citizenship in the military context are still being issued. For example, in late August 2019, USCIS published new rules restricting citizenship for children of troops abroad, the reach and implications of which have yet to be seen. See U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., PA-2019-05, Defining ‘Residence’ in Statutory Provisions Related to Citizenship (Aug. 28, 2019), https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/policymanual /updates/20190828-ResidenceForCitizenship.pdf [https://perma.cc/V9CF-HWXR].

Voter Turnout, FairVote (2019), https://www.fairvote.org/voter_turnout#voter_turnout _101 [https://perma.cc/C75K-QTVV].

John Gramlich, Jury Duty Is Rare, but Most Americans See It as Part of Good Citizenship, Pew Res. Ctr. (Aug. 24, 2017), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/08/24/jury-duty -is-rare-but-most-americans-see-it-as-part-of-good-citizenship [https://perma.cc/A3J3 -UMFP].

See Trends in State Courts: Special Focus on Family Law and Court Communications, Nat’l Ctr. for St. Cts. 98-99 (2016), https://www.ncsc.org/~/media/Microsites/Files/Trends %202016/Revitalizing-the-Jury.ashx [https://perma.cc/5VZ8-PFAE].

Citizenship Rights and Responsibilities, U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., https://www .uscis.gov/citizenship/learners/citizenship-rights-and-responsibilities [https://perma.cc /E983-M7TW].

Matthew Friedman, Just Facts: As Many Americans Have Criminal Records As College Diplomas, Brennan Ctr. for Just. (Nov. 17, 2015), https://www.brennancenter.org/blog/just-facts -many-americans-have-criminal-records-college-diplomas [https://perma.cc/J64W-4KEP].

Gretchen Livingston, Profile of U.S. Veterans Is Changing Dramatically as Their Ranks Decline, Pew Res. Ctr. (Nov. 11, 2016), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/11/profile -of-u-s-veterans-is-changing-dramatically-as-their-ranks-decline [https://perma.cc/S58B-JW58].

See Bill Ong Hing, Deporter-in-Chief: Obama v. Trump (Univ. of S.F. Law Research Paper No. 2019-03, 2018), https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3254680 [https://perma.cc/CFY7-4XLD]. Though popularly championed as an ally of immigrants after the advent of DACA, immigration advocates widely criticized President Obama as the “Deporter-in-Chief” due to his historically high numbers of formal removals. The bureaucratic machinery that allowed for this historic level of immigration enforcement has been used by President Trump to implement and enforce even broader and more draconian immigration measures—draconian measures he promised to enact from the campaign trail.