Title VII’s Statutory History and the Sex Discrimination Argument for LGBT Workplace Protections

abstract. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the Seventh Circuit have taken the position that Title VII’s bar to employment discrimination “because of . . . sex” applies to discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons. This interpretation follows from the ordinary meaning of the statute, read as a whole and in light of its purpose. If an employer fires a woman because she is married to another woman, rather than a man, the employer has, literally, acted “because of” her sex (if she had been a man, marriage to a woman would have been fine) and because of the sex of her partner. It is difficult to deny that “sex” is not at least one “motivating factor” in the employment decision, which is all that the current version of Title VII requires for liability. Moreover, this reading of Title VII accords with its purpose, which is to entrench a merit-based workplace where specified traits or status-based criteria (race, color, national origin, religion, and sex) are supposed to be irrelevant to a person’s job opportunities.

Treating antigay discrimination as a form of sex discrimination is not a new idea, but for several decades most federal judges have rejected it, and most members of Congress have ignored it. This, however, is an idea that has ripened over time. New circumstances have rendered the argument not only plausible but also compelling. The most significant new development has been evolving social facts and assumptions about sex minorities: in 1964, employees thought to be “homosexuals” were outside the scope of the merit-based workplace, because Americans believed them to be mentally ill, psychopathic, and predatory. Today, those views have been discredited. This shift in thought connects with a second new circumstance: a radically different constitutional baseline. As late as 2003, “homosexuals” could constitutionally be considered presumptive criminals, but the Supreme Court has for twenty years been developing a constitutional norm that gay people cannot be singled out for special legal exclusions without a rational public justification. Indeed, the Court has ruled that the constitutional right to marry applies to same-sex (i.e., “homosexual”) couples. It is constitutionally jarring to know that, in most states, a lesbian couple can get married on Saturday and be fired from their jobs on Monday, without legal redress.

A third new development has been the formal evolution of Title VII itself. Judges as well as commentators have largely ignored the “statutory history” of Title VII—its formal evolution through a process of amendment by Congress and authoritative interpretation by the Supreme Court. The Trump Administration and other skeptics of a broad reading of sex discrimination maintain that Title VII divides the world into males and females, and does nothing more than require employers to apply the same rules to both sexes. According to this view, antihomosexual workplace exclusions or harassment operates equally on both sexes (i.e., both lesbians and gay men are harmed). But the Supreme Court has authoritatively interpreted Title VII to bar gender stereotyping, which also operates to protect both male and female employees alike. Congress ratified and expanded upon that interpretation in its 1991 Amendments to Title VII, which also reaffirmed its statutory mission to ensure a merit-based workplace free from sex-based decision making, even when sex is but one “motivating factor” in the discrimination. Because LGBT persons are gender minorities and because anti-LGBT discrimination is rooted in rigid gender roles, Title VII today bars discrimination because of the sex of the employee’s partner/spouse, just as it bars discrimination because of the race or religion of his or her partner/spouse.

author. John A. Garver Professor of Jurisprudence, Yale Law School. I deeply appreciate excellent research assistance and editorial guidance from Eric Baudry, Yena Lee, Charlotte Schwartz, Daniel Strunk, and Todd Venook (all Yale Law School Class of 2019). I am also grateful for valuable comments from Martha Ertman, Steve Calabresi, Guido Calabresi, Sharra Greer, Heather Gerken, Abbe Gluck, Pat McGlone, John Davis Malloy, Judith Sandalow, Vicki Schultz, Amanda Shanor, Reva Siegel, Susan Silber, and John Witt, as well as participants at a Yale Law School faculty workshop.

Introduction

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 bars employment discrimination “because of . . . sex.”1 A successful part-time teacher at Ivy Tech Community College, Kimberly Hively, complained that the college refused to consider her for a permanent job because she is a lesbian. If true, does that refusal constitute discrimination because of sex? Because Title VII does not bar discrimination “because of . . . sexual orientation,” federal appeals courts have uniformly said “no” to this question—until the Seventh Circuit, sitting en banc, reconsidered the issue.2

Writing for the en banc, eight-judge majority in Hively v. Ivy Tech Community College of Indiana,3 Chief Judge Diane Wood offered two interconnected arguments to support the holding that an employer’s refusal to hire a lesbian constitutes discrimination because of sex. Reading the statute literally, judges in sex discrimination cases often ask whether the plaintiff has shown that the employer would have treated a similarly situated “comparator” (a person of the opposite sex) more favorably. If Hively had been a man, sexually cohabiting with or married to a woman, the college would have considered him for permanent employment on his merits. Ivy Tech allegedly rejected Hively out of hand because she was a woman partnered with another woman. Hence, she was allegedly denied the job “because of . . . [her] sex” as a woman rather than a man. This line of reasoning is often called the “comparator argument.”4

In the alternative, Chief Judge Wood reasoned that Hively was discriminated against because of the sex of her intimate associate (her partner).5 A precedential basis for this “associational discrimination argument” is Loving v. Virginia,6 where the Supreme Court ruled that state discrimination against interracial couples constitutes discrimination because of race. For the same reason that state discrimination against a black woman cohabiting with or married to a white man is race discrimination, Ivy Tech’s discrimination against a woman cohabiting with or married to another woman is sex discrimination. In the first case, the regulatory variable—the factor that changes the legal treatment—is the race of the associated person; in the second case, the regulatory variable is the sex of the associated person.

Writing for three dissenting judges, Judge Diane Sykes criticized these formal arguments as an excessively dynamic, “judge-empowering” interpretation of the statutory language.7 Focusing on the original meaning of the statutory text, Judge Sykes argued that “sex” in 1964 only meant one thing—the two biological sexes (male and female)—and could not have meant “sexual orientation,” a term not widely used in 1964.8 In contrast, Congress has in subsequent statutes, such as the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009,9 specifically prohibited discrimination because of “sexual orientation” as well as because of “sex,” indicating that the two terms have different meanings.10 In ordinary parlance today, Judge Sykes argued, no one would say that workplace gay-bashing constitutes “discrimination because of sex”; almost everyone would say that it is “discrimination because of sexual orientation.”11 Not only does “sexual-orientation discrimination spring[] from a wholly different kind of bias than sex discrimination,”12 but the only legitimate means to update the statute in this way is through the legislative process.13

Concurring in most of Chief Judge Wood’s opinion, Judge Joel Flaum (joined by Judge Kenneth Ripple) maintained that the text, read in light of the whole Act, supported Hively’s Title VII claim. Given the allegations in the complaint, Judge Flaum found it hard to deny that Ivy Tech excluded her at least in part either because of her sex (the comparator argument) or because of the sex of her romantic partner (the associational discrimination argument).14 In response to Judge Sykes’s point that this was just a case of sexual orientation discrimination, Judge Flaum observed that it had elements of both sex-based and sexual orientation-based discrimination.15 Because Title VII was amended in 1991 to bar sex discrimination even when sex is only one “motivating factor,” today’s statute supported Hively.16

In contrast to other judges in the majority, concurring Judge Richard Posner suggested that Chief Judge Wood’s opinion was not dynamic enough. He joined her majority opinion but also maintained, contrary to Judge Sykes, that judges should “update” statutes based upon current social norms and their understanding of the best workplace policy.17 Homosexuality has become sufficiently normalized in society that judges should dynamically interpret Title VII to reflect its most efficient deployment.

The same issue also recently divided the Eleventh Circuit. In Evans v. Georgia Regional Hospital,18 the panel, in an opinion by District Judge Jose Martinez, held that a lesbian might have a Title VII claim for sex discrimination if the employer denied her opportunities because of gender stereotyping but has no Title VII claim for simple sex discrimination, even if she was denied a job because she is romantically attracted only to women.19 Dissenting on the latter point, Judge Robin Rosenbaum argued that the gender stereotyping argument went further than the majority recognized and instead justified Title VII protection for female employees who depart from the deep stereotype that women should find romantic love with the right man, not the right woman.20 Concurring in Judge Martinez’s opinion, Judge William Pryor Jr. argued that Judge Rosenbaum’s interpretation would amount to an amendment, rather than an interpretation, of the statute.21 Counsel for Jameka Evans plans to petition the Supreme Court for review of the Eleventh Circuit’s decision.22

Chief Judge Robert Katzmann of the Second Circuit has also recently urged a reconsideration of his court’s precedent declining to apply Title VII to bar sexual orientation discrimination.23 Like Chief Judge Wood, Chief Judge Katzmann found persuasive both the comparator and the associational discrimination arguments;24 like Judge Rosenbaum, he opined that anti-LGBT discrimination involves gender stereotypes that the Supreme Court has ruled cannot be the basis for employment decisions in the merit-based workplace.25 Chief Judge Katzmann also addressed the argument, previously accepted by the Second Circuit, that Congress had “ratified” the previous court of appeals decisions because it did not override them in its 1991 Amendments and because it declined to enact any one of several dozen bills specifically seeking to bar sexual orientation discrimination. Following the Supreme Court, he cautioned against drawing legal meaning from “a proposal that does not become law. Congressional inaction lacks persuasive significance because several equally tenable inferences may be drawn from such inaction, including the inference that the existing legislation already incorporated the offered change.”26

Following Chief Judge Katzmann’s suggestion, the Second Circuit has granted en banc review of this issue in Zarda v. Altitude Express, Inc.27The EEOC filed an amicus brief in that case, defending its view that LGBT employees like Donald Zarda are protected by Title VII.28 The Trump Administration’s Department of Justice, however, subsequently filed an amicus brief supporting the opposite interpretation on precisely the grounds rejected by Chief Judge Katzmann, namely, that Congress ratified the older court of appeals cases when it amended Title VII in 1991 and when it rejected bills that would have amended Title VII or created a new statute to protect against sexual orientation discrimination specifically.29 In an appendix, the Justice Department’s brief listed sixty-two bills introduced in Congress between 1974 and 2017 that would have addressed, in a variety of ways, the treatment of sexual and gender minorities in the workplace. Like most proposed legislation, a large majority of the bills died in committee, without hearings or any kind of vote. Over the last forty years, congressional committees held hearings on ten of these bills, and three were voted upon by one chamber (failing 49-50 in the first case, passing one chamber in the other two cases).30

With such a dramatic split in the circuits and even within the executive branch, the issue should soon reach the Supreme Court.31 Ironically, the formalism of Chief Judge Wood’s and Judge Flaum’s approach would be attractive to the Supreme Court Justices (such as Justice Thomas) least inclined, ideologically, to read Title VII to protect LGBT employees and would be an incomplete analysis to some of the Justices (such as Justice Breyer) most likely to read Title VII more broadly. The whole act analysis suggested by Judge Flaum ought to be appealing to Chief Justice Roberts,32 but would the Chief be willing to interpret a civil rights law expansively? Will the Supreme Court divide along predictably ideological and political lines—or might the legal arguments provide a canvas to debate the issue in the relatively nonideological manner the Seventh Circuit did?33 A related issue is whether Title VII’s sex discrimination bar protects transgender employees. For reasons I find persuasive, Judge Pryor has joined Judge Rosemary Barkett’s panel opinion ruling that it does, a judgment followed by most other federal judges, including a recent Seventh Circuit panel.34 Note that Judge Pryor liberally interprets discrimination because of sex to include discrimination because of one’s self-reported sex and discrimination because of gender stereotyping, but is not willing to include discrimination because of the sex of one’s partner.

Hively, Evans, and Zarda not only tee up important substantive issues of job discrimination, but also methodological issues regarding the proper approach to statutory interpretation in general, and dynamic statutory interpretation in particular. Broadly speaking, the Seventh Circuit judges followed three different methodological approaches. Judge Sykes applied what she considered to be Title VII’s original meaning: the objective meaning (to a reasonable speaker) entailed by the statutory text, “discrimination because of . . . sex.”35 Judge Posner called for judicial dynamic interpretation of Title VII, whose original meaning, in his view, has been rendered obsolete by changed social and workplace norms.36 Chief Judge Wood followed a pragmatic approach that considers statutory text, purpose, and precedents, as well as relevant constitutional norms and directives.37 Chief Judge Katzmann is also an advocate of a pragmatic approach that considers various sources for understanding statutory meaning.38

A pragmatic approach is most consistent with the approach to statutory interpretation long followed by the U.S. Supreme Court. Part I of this Feature will suggest that the seemingly simpler approaches followed by Judges Posner and Sykes require consideration of the wider array of sources explored by Chief Judge Wood and by this Feature. Generally, Part I maintains that Title VII’s statutory plan—entrenchment of a merit-based workplace as regards the criteria listed in the law—must inform the analysis of any judge, whether she be an original meaning textualist, a dynamic interpreter, or a pragmatist. Original meaning analysis, properly set forth, produces a much more complicated inquiry than the arbitrary choices made by Judge Sykes. Dynamic interpretation requires better grounding in traditional legal materials than Judge Posner attempts. And a legal pragmatic analysis needs to explore more materials than Chief Judge Wood analyzes in her opinion for the court in Hively.

The main theme of this Feature is that any judicial interpretation of Title VII’s text, purpose, or precedents is incomplete, from any methodological point of view, without an exploration and understanding of the statutory history (congressional amendments and authoritative interpretations) as well as the legislative history of Title VII and its amendments. Part II will offer such an exegesis of Title VII’s statutory history, namely, its formal evolution through authoritative interpretation and congressional amendments. Part II will contrast statutory history, which has never been a controversial source of guidance in statutory interpretation, with legislative history, the internal congressional materials generated in the process of statutory deliberation and enactment, which has been controversial within the Court. Notwithstanding criticism, the Court still relies on legislative history tied to statutory text created by Congress. Indeed, Justice Scalia, the father of the strict new textualism, has said that judges should consult a law’s legislative history for the same reason he and other textualists consult the Federalist Papers in constitutional cases—namely, to help the judge understand the meaning of words, phrases, and structures Congress has enacted.39 Accordingly, Part II will examine the legislative history of Title VII and its amendments only insofar as they help us understand the meaning of the words, phrases, and structures actually enacted into law. Contrast this approach with the Department of Justice’s Zarda amicus brief, which has the vice of not tying its legislative inaction arguments to text adopted by Congress. Instead, the Department gestures toward a link to the 1991 Amendments without actually citing any relevant new statutory text.

Title VII’s statutory history establishes the following points of law that are relevant to Hively, Evans, and Zarda. First, Title VII is equally committed to purging the workplace of arbitrary sex-based, race-based, and religion-based criteria. Congress and, eventually, the Supreme Court have rejected the approach initially followed by the EEOC, whereby enforcement was focused on race discrimination, with discrimination because of sex and religion assuming a subordinate position. As the plain language suggests, the statute presumptively follows the same precepts for race-, sex-, and religion-based discrimination—except where the text explicitly creates a distinct regime, as it does for bona fide occupational qualifications, which are not available to justify discrimination because of race.40 Even employment decisions motivated only in part by a disapproved criterion are now questionable under the statute as amended in 1991.

Second, Title VII not only bars employment practices that treat all women differently from all men, but also bars practices that treat some men or some women differently because of their sex or because of the sex of their spouses or partners. Moreover, binding Supreme Court precedent, ratified and expanded by Congress in 1991, commits Title VII to the broader principle that employers cannot prescribe non-merit-based gender roles on both men and women equally. The same idea has been uncontroversial with regard to race among lower court judges.41

Third, at the same time Title VII was formally evolving, the Constitution’s treatment of LGBT persons has formally evolved. Between 1967 and 1996, authoritative Supreme Court decisions advised Congress and state legislatures that homosexual or bisexual persons could be treated as per se “afflicted with psychopathic personality” and that private nonprocreative sexual acts between consenting same-sex couples could be criminalized as felonies.42 Psychopaths and presumptive felons do not enjoy all the protections of a merit-based workplace, an important reason for Congress’s longstanding lack of interest in deliberating about any workplace rights for LGBT people. But, reflecting changes in social attitudes and in medical and psychiatric views, the Court changed the constitutional baseline in a series of landmark Fourteenth Amendment decisions handed down between 1996 and 2015.43 This dramatically evolving constitutional context upends the assumptions of the leading circuit court precedents excluding “homosexuals” and “transsexuals” from the protections of Title VII and further undermines the congressional acquiescence arguments made by the Trump Administration’s Justice Department in Zarda. That is, judicial precedents premised on the assumption that Congress and employers can discriminate against gay and lesbian employees because they are presumptive criminals or psychopaths not only can be but must be revisited once that presumption has not only been revoked but reversed.44

Part III pauses to summarize the lessons of our extensive investigation of Title VII’s statutory history. Looking forward, this Feature then addresses the possibility that an ideologically driven but textualist Supreme Court no longer effectively monitored by a gridlocked Congress will be tempted to impose an anti-LGBT reading on a statutory text, structure, and history that strongly support the plaintiffs’ claims in Hively, Evans, and Zarda. The web of statutory text, structure, precedent, practice, and constitutional background norms is so tightly interconnected and strongly hostile to reading LGBT employees out of the protections of Title VII’s merit-based workplace that an effort by the Supreme Court to turn back the clock through a stingy reading of the statutory text would probably be an embarrassment to original meaning jurisprudence. Indeed, a poorly researched textual analysis, divorced from statutory history, would amount to an assault on the rule of law itself. The predictability promised by the rule of law requires even the Supreme Court to respect the web of interconnected rules and neutral principles that administrators have created, judges have ratified or altered, and legislators have relied on when they revisit the statute through amendments and overrides. As the Seventh Circuit recognized in Hively, that web of rules and neutral principles supports a simple directive that Title VII’s merit-based workplace protects LGBT individuals.

I. the merit-based workplace and the meaning of title vii

A. The Merit-Based Workplace

Start with the normative ideal of a merit-based workplace, where all people would have and retain jobs based upon their ability to perform and would not be excluded from jobs or harassed at work because of personal characteristics irrelevant to their capabilities. This ideal is inspired by sociologist Max Weber’s contrast between a patriarchal culture, wherein economic and social structure was organized around status and personalized around the father or master, and modern culture, which seeks to organize production around objective, meritocratic rules, rather than subjective, caste-based practices.45 Under Weber’s framework, a merit-based workplace is axiomatic to the assumptions and practices of modern culture—and hence a highly desirable norm.

A wide range of modern normative philosophies would view the merit-based workplace as a worthy ideal. For example, most utilitarian thinkers, seeking the greatest good for the greatest number, would value such a workplace because it allocates resources much more efficiently and promises to reduce disruptive workplace practices (like hazing and harassment).46 Many philosophers of justice would endorse a merit-based workplace because it focuses evaluation on the individual and establishes baselines that are fair and just, the kind of rule that most of us would choose behind the veil of ignorance (i.e., we do not know what entitlements we would have in a world following the rule).47

Finally, many civil rights advocates and theorists, including feminists, would maintain that a genuine merit-based system would undermine the operation of prejudices and stereotypes that hold back women and minorities from equal opportunities in the workplace.48 Their vision of a pluralistic workplace is sometimes in tension with the utilitarian or economic vision, but as to many issues they press in the same direction. I should note here that the merit-based workplace is not a panacea, especially for inequities or discriminations faced by persons who are poor or come from disadvantaged backgrounds. My only point here is that such a norm enjoys support from a variety of perspectives and fits the aspirations of our society.

The merit-based workplace norm is dynamic. A 1964 statute barring job discrimination for reasons unrelated to people’s capabilities would not immediately have been applied to protect “homosexual” employees, as there was a social consensus that “homosexuals” were not capable of doing most jobs due to their inherent “psychopathic personality” and other mental disorders.49 In addition, every state but Illinois at that time considered “homosexuals” to be criminals by reason of their characteristic sexual activity (consensual sodomy).50 The same statutory language, read today, could protect gay people against discrimination, because both social facts and the law have changed: it can no longer seriously be maintained that homosexuality is evidence of psychopathy or mental illness, and consensual sodomy can no longer be a crime after Lawrence v. Texas.51 Indeed, a job discrimination law that authorized employers to discriminate against LGBT workers because of traditional stereotypes would be constitutionally suspect under Romer v. Evans,52 in which the Supreme Court ruled that laws excluding gay, lesbian, and bisexual persons from general legal protections without plausible justification (or because of antigay animus) violate the Equal Protection Clause.

Enacted as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, on its face, legislates the merit-based workplace as regards characteristics associated with race, color, national origin, religion, and sex—precisely the modern Weberian approach, as limited to the enumerated traits, whose consideration is presumptively not consistent with workplace meritocracy. While some utilitarian thinkers (including Judge Posner) argue that Title VII does not efficiently promote this meritocratic ideal, others have endorsed its mission.53 (And of course Judge Posner enthusiastically advanced Title VII’s mission by his concurring opinion in Hively.54) From most feminist perspectives, Title VII properly “seeks to . . . identify, and change, discriminatory employment practices that reinforce negative stereotypes and foster unnecessary difference and division, and . . . [to] endorse practices that encourage people to relate to each other as equals across boundaries of sex and race.”55 As Part II will demonstrate, the statutory and legislative history of Title VII not only makes clear that the merit-based workplace represented Congress’s plan for the statute, but also elaborates on the threats to that plan posed both by sexuality-based workplace discrimination and by gender stereotypes regarding the role of men and women in the family, the workplace, and society.

Like the generic statute described at the beginning of this part, Title VII in 1964 would not have been applied to ensure a liberal workplace for “homosexuals” or “transsexuals,” for those Americans were, literally, considered psychopaths, criminals, and enemies of the people—propositions that no longer enjoy respectable support. The question in Hively and the other recent cases is whether judges should interpret the current version of Title VII to include gay and lesbian employees within the merit-based workplace. To answer that statutory interpretation question, judges are supposed to consider (1) the text of the statute, including the whole act and the statute’s evolution through legislative amendments and repeals, (2) the legislative purpose, (3) Supreme Court precedents authoritatively interpreting the statute, (4) the legislative deliberations preceding and accompanying the enactment of the statute and its amendments, (5) the regulatory history of the statute and how agency interpretations interact with the legislative deliberations, and (6) larger constitutional, institutional, and social norms.56

These standard legal sources ought to be applied with an eye to the purposes of statutory interpretation as an operation of the government. Specifically, the purposes of statutory interpretation are (1) ensuring the rule of law (predictable and consistent application of concrete legal authorities using an objective, transparent method of analysis), (2) in a manner that respects the legitimate deliberation and actions of our democratically elected lawmakers, and (3) that reasonably adapts statutes to the evolving governance needs of society.57 In Hively, Judge Posner lionized the third element, dominating the other two,58 but I (like Chief Judge Wood and Judge Sykes) maintain that dynamic judges ought to pay close attention both to the operation of the democratic process and the most concrete sources of statutory meaning, namely, statutory text, structure, and precedent.

A central contention of this Feature is that the rule-of-law norms emphasized by Chief Judge Wood and Judges Flaum and Sykes complement rather than conflict with the updating needs emphasized by Judge Posner. To accomplish this synthesis, I shall examine standard legal sources that were not explored in Hively or Evans—namely, those reflecting authoritative interpretation and democratic deliberation. Subsequent congressional amendments, their legislative purpose and history, and administrative and judicial precedents provide democratic support for a synthesis of the approaches taken by Chief Judge Wood and Judge Rosenbaum (dissenting in Evans).

B. Original Meaning of Title VII

In Hively, Judge Sykes relied upon a simpler approach to statutory interpretation that has enjoyed enthusiastic support from many judges and some scholars. Following Justice Scalia, Judge Sykes invoked the original meaning of the statutory text, which bars employer discrimination “because of sex.”59 Is she right to say that the original meaning of this language requires faithful textualist judges to dismiss Hively’s claim? Several strict adherents of original meaning jurisprudence—notably Judges Frank Easterbrook and Kenneth Ripple—joined Chief Judge Wood’s Hively opinion, which suggests that the original meaning inquiry might not be so straightforward.

As enacted in 1964, Title VII did not define “sex.” Federal judges often start with standard dictionaries of the era to think about statutory meaning of undefined terms.60 Judge Sykes found that “sex” in 1964 had only one meaning—the division of humanity into biological males and females.61 Such a simple understanding is incomplete, at best. The unabridged 1961 printing of Webster’s (the most-cited dictionary in Supreme Court opinions) defined the word “sex” to mean three different things:

- “[o]ne of the two divisions of organisms formed on the distinction of male and female,” or sex as biology;

- “[t]he sphere of behavior dominated by the relations between male and female,” or sex as gender (man=masculine, woman=feminine);

- “the whole sphere of behavior related even indirectly to the sexual functions and embracing all affectionate and pleasure-seeking conduct,” or sex as sexuality.62

Webster’s was not alone in this broader array of ordinary meanings that were, in 1964, associated with the term “sex.”63 Can it really be maintained then that “sex” had but one meaning in 1964?

Consider a concrete example. In the 1960s, an increasing number of schools had “sex education” programs. What topics might have been covered in programs teaching about “sex”? According to Judge Sykes’s definition, “sex education” would cover only sex as biology, teaching kids the morphological differences between men and women. But might a sex education course also teach about gender roles, either descriptively or prescriptively? And surely a sex education course might teach about human sexuality—including variation in sexual practices as well as the mechanics and norms relevant to reproductive sex.

In fact, sex education courses of the 1960s offered much more discussion about gender roles and human sexuality than they did about the biological differences between the sexes.64 For example, the sex education curriculum followed by many secondary schools in California asked students to engage in role-playing exercises contrasting authority relations between husbands and wives; high school students tackled “changing male and female roles” by discussing differing interpretations of masculinity, femininity, and differentiated sex roles.65 As part of a ninth-grade unit on “sexual deviations,” California’s sex education students learned that homosexuality “has been known throughout human history and occurs in many societies.”66

The foregoing analysis suggests that the meaning of “sex” in 1964 was not as one-dimensional as Judge Sykes asserted. Judge Sykes also maintained that discrimination “because of sex” must mean something different than discrimination “because of sexual orientation.”67 That is a better argument, but has Judge Sykes posed this question in a neutral manner? Chief Judge Wood posed the textual question another way: What is the relationship of “discriminate because of sex” and “discriminate because of the sex of your spouse/partner”? Is original meaning textualism nothing more than a clever shell game, where each side can secure the “original meaning” it prefers by the way it poses the inquiry?

Stick with Judge Sykes’s manner of posing the question. The honest textualist still needs to explore the exact relationship of “discriminate because of sex” and “discriminate because of sexual orientation.” Do the two types of discrimination have no overlapping application, as Judge Sykes assumed? Might they overlap (Judge Flaum’s view)? Or might one kind of discrimination be a subset of the other (Chief Judge Wood’s perspective)? Overlapping or subsumed terms are common in antidiscrimination law. Title VII bars discrimination because of skin color, nationality, and race—terms that overlap considerably. Many state and municipal laws prohibit discrimination both because of sex and because of pregnancy, even though the latter is widely accepted as a subset of the former.68 Other state statutes, as well as Title VII today, explicitly define “discriminate because of pregnancy” as a subset of “discriminate because of sex.”69

As Judge Flaum argued, it is difficult to believe that an employer who objects to female employees because of the biological sex of their romantic partners is not discriminating at least in part “because of sex” even if the statutory term is understood only to entail sex as biology.70 As amended in 1991, Title VII provides that an employer can violate the law in mixed-motive cases, so long as one significant “motivating factor” is sex, even if “other factors also motivated the practice.”71 This is an example of how statutory interpretation can be highly dynamic. Because of this and other amendments, Title VII means something different today than it did when it was enacted in 1964—based upon new statutory texts adopted by our democratically elected representatives. Thus, even if Judge Sykes were right about the original 1964 meaning of “sex” and its relationship to “sexual orientation,” the 1991 amendment requires her to demonstrate that “sex” is not even a motivating factor when an employer discriminates against an employee because of the sex of her partner (or because of her sex, in light of the partner’s sex). For this reason, Judges Flaum and Ripple emerge as the most faithful agents of a strictly textual meaning for Title VII.

C. Dynamic Title VII

Because she ignored most of the relevant statutory text and imposed arbitrary, unhistorical choices on the text she did analyze, the application of Judge Sykes’s approach is just as “judge-empowering” as Judge Posner’s openly dynamic approach. The challenge for both judges would be to demonstrate that their creative readings of Title VII rested upon legitimate reasoning from legal authority and relevant facts about the world. Setting aside his earlier criticisms of Title VII, Judge Posner argued that judges ought to expand the merit-based workplace to include lesbian and gay employees, based upon current knowledge about these employees.72 Judge Sykes, in contrast, was reluctant to apply the statute to create new liabilities for employers without more explicit guidance from Congress, which has repeatedly failed to act upon bills to bar workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation (and, recently, gender identity).73 Both Judge Posner and Judge Sykes would have written more persuasive legal opinions if they had been attentive to what Congress actually did when it enacted the law in 1964 and when it subsequently amended the law or adopted related statutes. In my view, what Congress actually does—the point of statutory history—is more important than what Congress fails to do—the point of Judge Sykes’s and the Justice Department’s neglected proposals argument. (Indeed, strict textualists are committed to following the original meaning of the words Congress actually enacted—not words that it later failed to enact—and have rejected the idea that a subsequent Congress can tell us the original meaning of a previously enacted statute.74)

Authoritative judicial interpretations of the governing statute are another inevitably dynamic source in statutory interpretation; those interpretations will affect the path taken by the statute. In Hively, neither Judge Posner nor Judge Sykes applied Supreme Court Title VII precedents with notable enthusiasm, an attitude at odds with the hierarchical structure of the federal judiciary and, often, with the rule of law itself.75 Lower court judges are expected to treat Supreme Court precedents seriously—and should typically follow them faithfully and not begrudgingly. While ambiguous Supreme Court precedents will inevitably be applied dynamically by lower court judges,76 these lower court judges have an obligation to justify their views that Supreme Court precedents offer them no clear guidance. In my view, such a justification requires judicial attention to legislative deliberations about the statutory purpose(s).

In the end, I believe that the methodological debate between original meaning (Judge Sykes) and dynamic interpretation (Judge Posner) has little to do with the proper interpretation of Title VII. A statute—like Title VII—that has been authoritatively interpreted, amended by Congress on several occasions, and then reinterpreted is a statute where original meaning itself is a dynamic process and involves updating. The clashing interpretations in Hively cannot be legally evaluated without understanding the formal evolution of Title VII—from its enactment in 1964, through its amendment in 1972, continuing with the congressional override of the Supreme Court’s pregnancy discrimination decision in 1978, referencing the EEOC’s application of Title VII to sexual harassment and the Supreme Court’s and Congress’s ratification of that application, emphasizing the Supreme Court’s landmark decision holding that workplace exclusions based on gender stereotypes can violate the statute, exploring Congress’s ratification and expansion of this norm in the 1991 Amendments, and finally, including the Family and Medical Leave Act in 1993. To that evolution I now turn.

II. the three faces of discrimination “because of sex”: ensuring a merit-based workplace

In surveying the statutory history of Title VII, I shall apply each of the three meanings that “sex” had in 1964 and, in the process, more deeply explore how those meanings are interrelated. The statutory history establishes, as a matter of relatively settled law, that Title VII guarantees individual employees a merit-based workplace where their opportunities will not be impeded by their biological sex (or that of their intimate associates), descriptive or prescriptive gender stereotyping, or sexualized harassment.

The statutory history is highly relevant to all the judges considering the Hively/Evans/Zarda issue. Contrary to Judge Sykes and the Trump Administration, Title VII is not simply class-based legislation, aimed only at employer policies or workplace conditions that disfavor women and favor men, or disfavor blacks and favor whites, or disfavor Catholics and favor Protestants. Instead, as stated by its text and entrenched by its statutory history, Title VII operates as classification-based legislation, aimed at employer policies or workplace conditions that disadvantage any employee because of her or his race, sex, or religion—including the race, sex, or religion of her or his intimate associates. (These classifications have traditionally burdened blacks, women, and Catholics more than whites, men, and Protestants, but the statutory command also protects whites, men, and Protestants against improper discrimination.) The statutory history also makes clear that “because of sex” has a broad meaning that includes gender and sexuality as well as biological sex. Finally, the history supports my intuition that you cannot linguistically or conceptually separate biology, gender, and sexuality when talking about “sex.” Workplace rules that arbitrarily exclude or disable employees because of their race, sex, or religion are suspect under Title VII, even when they apply to whites as well as blacks, men as well as women, Catholics as well as Protestants, and gays as well as straights.

Title VII’s statutory history has created a web of interconnected rules and principles that have been responsive to emerging facts about what undermines the possibility of a merit-based workplace for all employees—the pervasiveness and toxicity of sexual harassment is one example, and the falsity of antigay stereotypes is another. As administrators, judges, and legislators have responded to our evolving understanding of the workplace, they have crafted a series of legal rules and precedents that render the exclusion of LGBT employees from Title VII increasingly anomalous and profoundly unworkable. In light of the Supreme Court’s recent Fourteenth Amendment precedents, the blanket exclusion is constitutionally problematic as well.

The materials that follow provide some interesting arguments that might enrich the approaches of Judges Sykes and Posner. As you read the statutory history, consider the important role Congress has played in updating the statute (an idea that gives Judge Sykes some ammunition), but also the ways in which Title VII jurisprudence has worked itself into a hopeless muddle if interpreted to exclude sexual orientation claims (a practicality that supports Judge Posner). On the whole, Title VII’s statutory history suggests that the opinions of Chief Judge Wood and Judge Rosenbaum, read together, provide a way forward consistent with the rule of law.

A. Sex as Biology: Relational Discrimination

Chief Judge Wood’s formal argumentation assumed that women and men are separate biological sexes and reasoned that discriminating against a woman (like Hively) because she is romantically involved with another woman is discrimination “because of . . . sex.” Recall that two different kinds of arguments flow from this proposition. The first is the comparator argument: if Hively had been a man (the sex-based comparator), she would not have been discriminated against, because Ivy Tech would not have excluded men romantically involved with women. “But for” Professor Hively’s sex, she would not have been excluded from consideration by the college.77

The second kind of argument, which Chief Judge Wood also offered, points to associational discrimination based on Loving v. Virginia78 and, implicitly, McLaughlin v. Florida.79 In the South as late as the 1960s, different-race couples were subject to special penalties for marriage (Loving) and sexual cohabitation (McLaughlin) not applicable to same-race couples. In both cases, the Supreme Court treated the state rules as discrimination because of race.80 Chief Judge Wood read Loving (and I read McLaughlin) for the idea that discrimination because of one’s association with a person of a different race is a cognizable form of discrimination. By analogy to Loving, Hively was discriminated against because of her romantic association with someone of the same sex. As Andrew Koppelman has long argued, “If a business fires Ricky, or if the state prosecutes him, because of his sexual activities with Fred, while these actions would not be taken against Lucy if she did exactly the same things with Fred, then Ricky is being discriminated against because of his sex.”81

Notice that both the comparator point and the analogy to Loving and McLaughlin are standard original meaning arguments: they are both linked to the original text of Title VII as enacted and amended by Congress. Handed down shortly after Congress adopted Title VII, McLaughlin was the leading Supreme Court case on this issue in 1964. Loving was the leading case when Congress expanded Title VII in the 1972 Amendments. (Unlike the Department of Justice and Judge Sykes, I am not relying on circuit court decisions; Supreme Court decisions are the authoritative final interpretations of the Constitution and federal statutes, of which Congress is presumed to be aware and in fact does follow fairly carefully.82) To say that members of the 1964 Congress themselves would not have drawn the conclusions Chief Judge Wood draws from this text is the sort of counterfactual speculation that discredited the “original intent” arguments made against Loving.83 As a matter of original legal meaning, firing a white employee dating a black woman because of prejudice against “racial mixing” would have been discrimination “because of race” in 1964 and in 1972. In parallel fashion, why then would it not be discrimination “because of sex” to fire a female employee because she is dating a woman?

Judge Flaum’s concurring opinion treats the comparator argument and the associational discrimination argument as more or less the same claim.84 I find Chief Judge Wood’s separate analysis useful, but—inspired by Judge Flaum—I should like to link both of her arguments with the concept of relational discrimination. Relational discrimination refers to adverse treatment of an individual because of her relationship to others; relational discrimination because of a regulated trait (race, ethnicity, religion, sex) refers to adverse treatment where that relational trait is the variable that determines who is discriminated against.85 An employer’s discrimination against a white woman married to a black man is relational discrimination because of race—either the race of the woman (white) or of her spouse (black) or, best conceived, the relationship or interaction between the two. Likewise, discrimination against Kimberly Hively because she was romantically attracted to women rather than men was relational discrimination because of sex—Hively’s sex or her partner’s sex or, best, the relationship or interaction between the two.

Notice that relational discrimination disrupts the narrative that Judge Sykes and the Trump Administration’s Department of Justice offer for their view that “because of sex” cannot be read literally (Hively would have been treated differently if she had been a man who loved women) or cannot be read to mean “because of the sex of her partner.” By their account, antigay employment policies or practices do not violate Title VII because they involve “differential treatment of gay and straight employees for men and women alike.”86 Their assumption is that discrimination because of sex must affect men or women in different ways. The text of Title VII, however, is inconsistent with that view; Section 703 does not announce protected “classes” of employees but, instead, sets forth status-based “classifications” (race, sex, etc.) that cannot be the basis for workplace discrimination. A classification-based approach can apply equally to all classes, in contrast to the class-based approach hypothesized by Judge Sykes and the Trump Administration—without citing a single provision of Title VII. For example, it would violate Title VII for a secular business to hire only Roman Catholics, but it would also be a violation for the secular business to refuse to hire employees who say they are religious but who do not attend religious services every week. The latter policy affects Catholics and Protestants the same way, but that does not protect it from the merit-based rules of Title VII. The same point, of course, can be made about Loving and McLaughlin: the state policies affected white people and people of color the same way, but they still represented unconstitutional discrimination because of race.

Consistent with this text and with the analogy to Loving, the original meaning of Title VII is that antimiscegenation employment policies violate Title VII, even though they do not involve “differential treatment” for black and white employees (who are treated alike by the employer who does not tolerate interracial intimacy). The Justice Department and Judge Sykes can escape the Loving analogy only by claiming that discrimination because of sex is less important than or has a different structure than discrimination because of race or discrimination because of religion for that matter. Like their other arguments, they cite no statutory text for this proposition. What is the point of original meaning textualism when its adherents ignore statutory text that cuts against their desired result or argumentation?

Moreover, the Trump Administration and Judge Sykes’s special treatment of sex discrimination is inconsistent with the statutory history of Title VII. After public debate and statutory amendments, Title VII targets sex discrimination with as much force and in the same way it targets race discrimination. That includes relational discrimination because of either sex or race (or religion).

1. The Early History of Title VII and the 1972 Amendments

Administrators and judges were slow to apply Title VII’s sex discrimination bar vigorously, in part because they believed the primary statutory mission to be eradication of race-based discrimination and did not think Congress expected them to dislodge traditional gender roles or, perhaps, to do much about workplace sex discrimination at all.87 Indeed, many considered the sex discrimination amendment to Title VII to have been either a joke or a subterfuge plotted by its sponsor, Representative Howard Smith, a well-known foe of racial integration but in fact also a close ally of the women’s rights movement.88 As scholars have documented, the joke or subterfuge reading of the sex discrimination amendment is greatly exaggerated, at the very least.89 Nonetheless, for some years it had traction as a reason or an excuse for decisionmakers to read the sex discrimination bar to be much narrower than the race discrimination bar. Under such circumstances, the Loving analogy would have been a much less persuasive argument.

After the EEOC initially took the absurd position that employers could openly advertise jobs in a sex-segregated manner, female activists and lawyers from various perspectives created an umbrella group, the National Organization for Women (NOW), specifically to resist the EEOC’s narrow view of sex discrimination.90 More faithful text-based decisions from agencies as well as courts followed that feminist educational and political effort. In its first Title VII sex-discrimination case, Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corporation, decided in 1971, the Supreme Court unanimously overturned an employer policy refusing to employ women (but not men) with pre-school-age children.91 The unanimous Court reasoned that Title VII enforced a merit-based workplace by reference to classifications, not classes. “Section 703 (a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires that persons of like qualifications be given employment opportunities irrespective of their sex.”92 Moreover, it is apparent that the employer was not discriminating exclusively based upon sex as biology, as 75-80% of those hired were women. Instead, the employer was primarily discriminating because of sex as gender role (women like Ida Phillips should be at home tending the kids) and even sex as sexuality (women with children were presumably sexually active). Thus, from the very first Supreme Court interpretation, discrimination because of sex had a broader meaning than Judge Sykes supposed.

After extensive hearings and floor debate, Congress in the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 extended Title VII to apply to federal, state, and local government employees and expanded the EEOC’s enforcement authority.93 Because Congress extended Title VII’s application to state employees under the authority of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court has ruled that Congress acted to rectify unconstitutional state sex discrimination, such as longstanding rules barring female employees from job opportunities, and surely including the gender-stereotyping rule struck down the year before in Martin Marietta.94 Such an assumption is amply supported by the congressional deliberations, which show that the drafters of the Act agreed with NOW and other groups that the workplace needed to be open to all workers, regardless of sex, and that state and local governments were pervasively violating that norm. The committee reports endorsed the approach to Title VII advanced by NOW and (by 1972) the EEOC: sex discrimination “is no less serious than other prohibited forms of discrimination,” including race discrimination.95 The reports further stated that the EEOC and the courts should make every effort to enforce the sex discrimination bar vigorously.96 Support for progressive views on the statutory sex discrimination ban and a stronger EEOC found voice in both contemporary feminist scholars97 and members of Congress in public deliberation.98 After the 1972 Amendments, which repeatedly equated the evils of sex discrimination with those of race discrimination, the Loving analogy becomes much more cogent. Indeed, 1972 is a key moment for that argument in another way.

The same year that Congress invoked its authority to enforce constitutional equality guarantees in the 1972 Amendments to Title VII, it passed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) by overwhelming majorities and sent it to the states for ratification. The ERA would have amended the Constitution to prohibit government discrimination “on account of sex,” similar to the Title VII language. A major concern with the ERA was the associational discrimination point, raised in 1970 congressional testimony by Paul Freund of Harvard Law School. Applying the logic of Loving, Professor Freund argued that for the same reason that denying different-race couples marriage licenses constitutes discrimination because of race (and is unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment), denying same-sex couples marriage licenses would be discrimination because of sex (and thus probably unconstitutional under the ERA).99

Citing Freund’s testimony, ERA opponent Senator Sam Ervin introduced an amendment to the ERA: “[The ERA] shall not apply to any law prohibiting sexual activity between persons of the same sex or the marriage of persons of the same sex.”100 Senator Birch Bayh, the ERA’s floor manager, opposed the Ervin Amendment because “the concern legitimate at first blush dissipates and indeed disappears in toto.”101 The Senate rejected the Ervin Amendment. We cannot know the precise reasons various senators had in mind when they voted against the Ervin Amendment, but the public record does demonstrate that Congress was on notice that the nation’s leading authority on the Constitution (Professor Freund) believed that the legal meaning of discrimination “on account of sex” carried with it the relational discrimination meaning established by Loving. And at the same time Congress was amending Title VII in 1972, it was aware of precise language that could be used to head off the application of Loving to protect same-sex couples and “homosexual” employees.

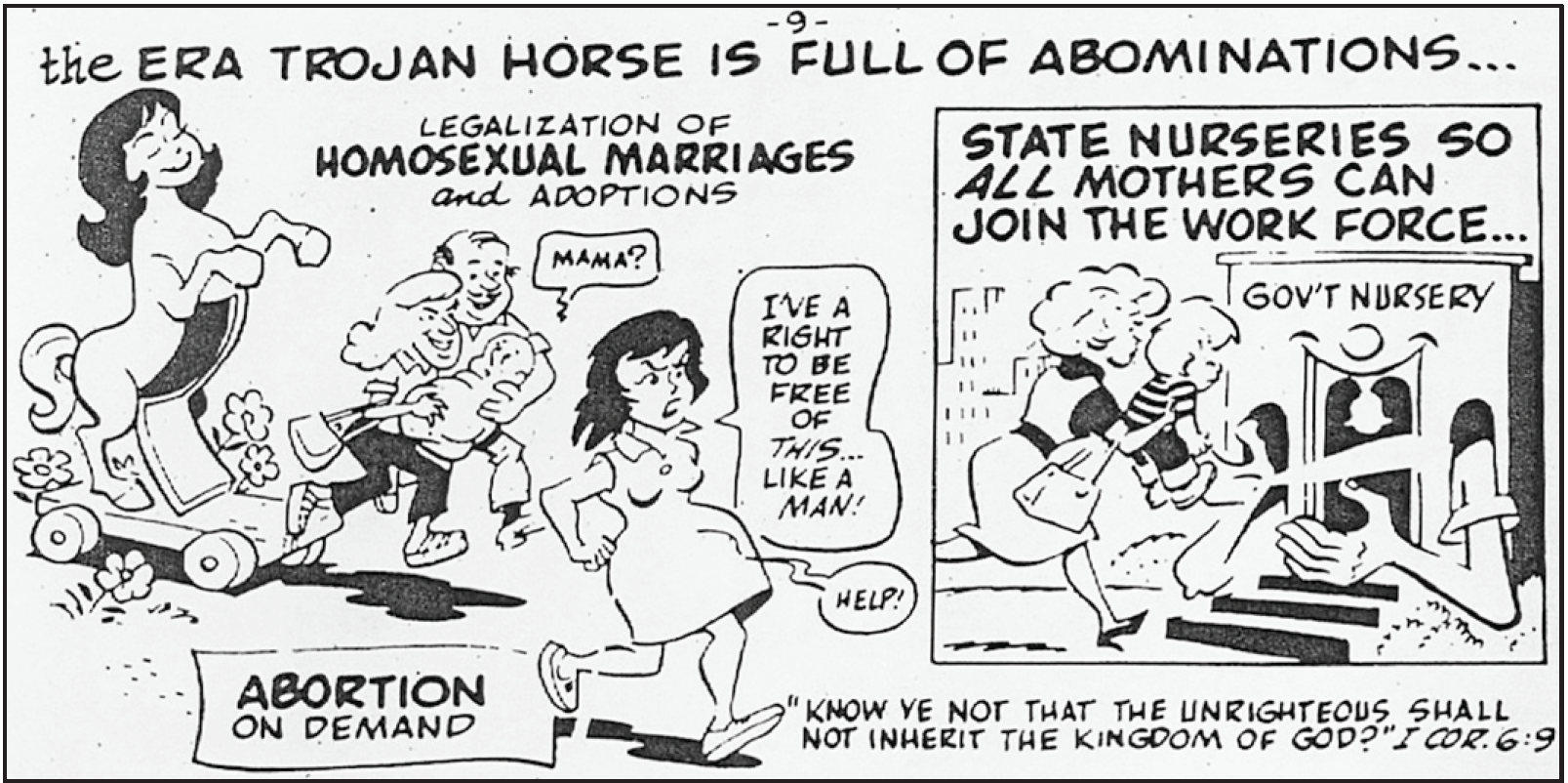

Like Senator Ervin, ERA ratification opponents, ambivalent state legislators, and many engaged voters agreed with Professor Freund’s argument. Phyllis Schlafly, the founder of STOP ERA, made this argument a key part of her successful campaign to slow down and ultimately prevent the ERA from securing the needed ratification from 38 state legislatures.102 Consider the STOP ERA cartoon below. As you study the cartoon, notice how Mrs. Schlafly understood “on account of sex” mainly in terms of sex as gender and sex as sexuality. Implicitly, the cartoon’s baseline is that sex as biology, sex as gender, and sex as sexuality are normatively interrelated. Fated by biology, women’s role is to bear and rear the marital children, whose well-being is thwarted by a strict rule against sex discrimination, for such a rule would generate “homosexual marriages and adoption” and a culture of “abortion on demand.” The cartoon is roughly contemporaneous with the 1972 Amendments to the 1964 Act. Is it completely clear, as Judge Sykes maintained, that no one would have understood a rule against discrimination “because of sex” to secure rights for gay people?

Due in part to Mrs. Schlafly’s efforts and popular receptiveness to her arguments, state ratifications slowed to a trickle after 1973—and a new ally ensured that STOP ERA would not prevail in the states that had not yet ratified. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) came out against the ERA in January 1975, on the eve of a vote in the Utah Legislature (which swiftly rejected the ERA). Like STOP ERA, the LDS Church found the Loving analogy a persuasive reason to reject the ERA.

figure 1.

stop era’s interpretation of discrimination “on account of sex”103

Thus, the LDS leadership expressed grave concern that “passage of the ERA could extend legal protection to same-sex lesbian and homosexual marriages, giving legal sanction to the rearing of children in such homes.”104 Because the ERA barred any state discrimination “on account of sex,” it might bar a state from denying marriage licenses to all-male or all-female couples. LDS opposition through massive grass-roots activism by Mormon congregants was critical to defeating the ERA in the period after January 1975.105

In short, the Loving analogy accepted by the Seventh Circuit in Hively has longstanding historical roots that might have been known to the Congress that adopted the 1964 Act (McLaughlin would be decided later that year) and would surely have been known to the Congress that passed the 1972 Amendments (the same Congress that passed the ERA). In any event, as a matter of statutory interpretation doctrine, the Supreme Court routinely “attributes” to Congress “knowledge” of widely recognized legal parallels and terms of art.106

To be sure, the Supreme Court in the 1970s would not have ruled that Title VII protected gay employees against discharge—not because the Loving analogy was illogical, but because so few LGBT employees were out of the closet at work and the employees who were “out” (or whose gender-bending appearance and behavior made them “stand out”) were widely considered sick, depraved, conspiratorial, disturbing, and even criminal. Thus, the Court could easily have agreed with discriminatory employers that being straight, or at least hiding in the closet (don’t ask, don’t tell), was a bona fide occupational qualification under Title VII.107 At the very least, the issue was not ripe for Supreme Court resolution. Indeed, right before the states started to debate the ERA, the Supreme Court summarily refused to consider the Loving analogy as a constitutional matter in its first same-sex marriage case.108

During the ERA debate of the 1970s, a few lower courts went further. In Smith v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Co., the Fifth Circuit ruled that an employer could discriminate against a man because he was “effeminate.”109 The court rested its reasoning on the premise that Congress only intended to guarantee equal job opportunities to men and women and so did not intend to protect employees whose gender traits did not perfectly match their employers’ expectations.110 In Blum v. Gulf Oil Corp., the Fifth Circuit, in dicta, cited Smith to opine that “discharge for homosexuality is not prohibited by Title VII.”111 A handful of lower court opinions in the 1970s also held that Title VII provided no relief for transgender employees discriminated against because of their asserted sex.112

2. The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978

Another reason the Loving analogy would not have succeeded in the 1970s is that the Supreme Court remained unwilling to apply Title VII’s sex discrimination bar as seriously as it applied the race discrimination bar. In General Electric Co. v. Gilbert,113 the Court interpreted Title VII to allow employers to exclude pregnancy benefits from their health care and disability insurance. Even though the pregnancy exclusion only affected female employees, the Court held that the policy was not disparate treatment because of sex. Central to the Court’s reasoning was its earlier interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause to allow states to exclude pregnancy benefits from state disability plans; in both Gilbert and the earlier constitutional precedent, the Court held that it is not discrimination because of sex unless the policy treats women differently from similarly situated men.114 The Court seemed to believe that there were no male comparators to pregnant women—and the Court explicitly stated that denying pregnancy benefits is not discrimination because of sex, as “traditionally” understood (and as the Court had previously ruled in the constitutional case).115 Because the statute put men and nonpregnant women in one category, and pregnant women in the other, the exclusion was not, strictly speaking, “because of sex.”116 Denying women Title VII protection because only a subgroup of women were disadvantaged, the Court thus took a narrow view of the statutory purpose. The Court also held that the policy was not unlawful disparate impact discrimination, even though any policy with such a strong and exclusive impact on employees of color would surely have been invalidated.117

The Gilbert approach might offer a counter to Chief Judge Wood’s formalist argumentation: Ivy Tech was not discriminating against women as a class, and many people in the 1970s believed that homosexuality was the result of chosen behavior rather than an immutable characteristic of one’s biological sex. There is an echo of this approach in Judge Sykes’s Hively dissent118 and in Judge Pryor’s concurring opinion in Evans119—but this approach is inconsistent with the statute as written in 1964 and as amended in 1972 and 1978.

Responding strongly to Gilbert’s result and reasoning, women’s groups took their case to Congress—which thoroughly repudiated Gilbert in the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 (PDA).120 The congressional bipartisan super-coalition that supported the PDA repeatedly expressed the view that Gilbert was not only wrongly decided, but also completely misguided in its reasoning and approach to sex discrimination. “By concluding that pregnancy discrimination is not sex discrimination within the meaning of title VII, the Supreme Court disregarded the intent of Congress in enacting title VII. That intent was to protect all individuals from unjust employment discrimination, including pregnant women.”121 The PDA added pregnancy and related medical conditions to Title VII’s definition of “sex” and further provided: “women affected by pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions shall be treated the same for all employment-related purposes, including receipt of benefits under fringe benefit programs, as other persons not so affected but similar in their ability or inability to work.”122

The italicized text embodies the regulatory philosophy animating the 1964 Act and the 1972 Amendments, as well as the angry 1978 override. The governing principle is the merit-based workplace, where “ability or inability to work” is the appropriate criterion, and where sex-based exclusions are disallowed or must be justified by the legitimate needs of the business. Reflecting the ability-to-work approach to sex discrimination evident in Congress’s deliberations in 1977-78, Supreme Court decisions since the PDA have generally interpreted Title VII (as amended) to cover any kind of sex-based classification, including those affecting only a small percentage of women or men in the workplace.123

Enactment of the PDA provided the occasion for the Supreme Court to apply Title VII to a matter of relational discrimination. In guidance to employers soon after the PDA took effect, the EEOC opined that health and medical insurance policies could no longer deny pregnancy benefits to spouses of employees, as well as to employees themselves.124 This guidance targeting relational discrimination could have been justified by the same kinds of associational discrimination or comparator arguments that Chief Judge Wood invoked in Hively. Female employees married to men received pregnancy benefits as part of their family health insurance, but male employees married to women did not. As a formal matter, the sex of the employee (the comparator argument) or of the spouse (the associational discrimination argument) is what triggered different treatment. Employers objected that relational discrimination such as this was beyond the coverage of Title VII, even after the PDA.

In Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co. v. EEOC,125 the Supreme Court agreed with the EEOC. The Court announced that the PDA had not only overridden the Gilbert result, but had also renounced its reasoning. Ruling that the company’s relational discrimination was “because of sex,” Newport News relied upon the same kind of comparator argument later deployed in Hively. The majority opinion held that the original Title VII (before the PDA), properly interpreted, barred employment practices “treat[ing] a male employee with dependents ‘in a manner which but for that person’s sex would be different.’”126 In other words, Title VII from the beginning had been a legislative endorsement of the merit-based workplace, for the benefit of male as well as female employees. To the extent Gilbert was decided under different premises, it had been repudiated by the PDA. Newport News also conclusively abrogated the Gilbert reasoning that discrimination affecting only a sex-based subgroup is not sex discrimination. As a matter of Title VII doctrine, Newport News reflects the Court’s application of Title VII to relational discrimination and confirms the comparator argument as a valid form of reasoning about whether there is discrimination because of sex.127

Newport News did not explicitly rely on the associational discrimination argument, but lower court decisions since 1975 have all but uniformly interpreted Title VII to regulate discrimination because of the race or ethnicity of one’s intimate associates.128 The Supreme Court, in another statutory context, has also accepted the associational discrimination argument and the Loving principle that race-based discrimination is presumptively illegal even when it equally affects all races (that is, when people with Caucasian as well as African or Asian or Latino backgrounds are all similarly formally affected). Interpreting the Internal Revenue Code, the Supreme Court in Bob Jones University v. United States unanimously treated the university’s bar to different-race marriage and dating to be simple race discrimination.129

Loving’s reasoning ought not be limited to race. If an employer is willing to hire Catholics but not Catholics who marry outside their faith, surely the employer has engaged in discrimination “because of religion,” also generally prohibited by Title VII. The EEOC Compliance Manual notes that “Title VII prohibits discrimination against an individual because s/he is associated with another person of a particular religion. For example, it would be unlawful to discriminate against a Christian because s/he is married to a Muslim.”130 A New York appellate court found an associational discrimination claim based on religion cognizable under the New York State Human Rights Law, under which claims are “analytically identical to claims brought under Title VII.”131 Admittedly, this area of law is undeveloped, perhaps because few employers openly discriminate in this way.132

As consistently applied by the EEOC and lower courts, Title VII applies to race-based and religion-based employer rules or practices that affect all races and all religions equally. Unless Title VII’s bar to sex-based discrimination is analytically different than its bars to race-based and religion-based discrimination, Title VII applies to sex-based rules or practices that affect men and women equally—contrary to the Hively dissent, the Evans majority, and the Justice Department’s position in Zarda. Interestingly, there is a great deal more to be said about this stance, which receives support in some of the state marriage equality cases. Those cases suggest a deeper understanding of judges’ resistance to the sex discrimination argument for gay rights.

3. Constitutional Challenges to Same-Sex Sodomy Laws and Same-Sex Marriage Bars

There is a broader point to be made about the associational discrimination argument. As previous scholars have argued, the Loving analogy has special bite for lesbian, gay, and bisexual employees, because sexual orientation itself is intrinsically relational.133 For gay men, lesbians, straight people, and bisexuals, sexual orientation is relational to another person’s sex—whether oriented toward the same biological sex (gay), the “opposite” biological sex (straight), or both (bisexual). Typically, a lesbian is subject to discrimination not because of her sexual activities (such as oral sex, an activity most Americans enjoy), but because of the biological sex of her partner. Constitutional challenges to laws discriminating against lesbian and gay persons illustrate this point, as well as its complexities.

This phenomenon is apparent in Lawrence v. Texas,134 in which the Supreme Court constitutionally protected two men engaged in private consensual sex from being penalized by the Texas “homosexual conduct law.” The law’s command was simple: “A person commits an offense if he engages in deviate sexual intercourse with another individual of the same sex.”135 Deviate sexual intercourse was defined to include anal sex, oral sex, and sex toys.136 Two persons of different sexes could engage in oral sex without a legal problem; indeed, a gay man and a lesbian (i.e., “homosexuals”) could lawfully engage in consensual oral sex with one another, consistent with the Texas statute.137 Even though the statutory crime was only defined by reference to “sex” and was completely relational (two or more people defined by “sex” have to be acting in concert), the Supreme Court majority opinion assumed that the objects of the statute were “homosexual persons”138 or “homosexuals, lesbians, [and] bisexual[s],” as the majority opinion put it in one passage.139 Justice O’Connor’s concurring opinion said this: “The Texas statute makes homosexuals unequal in the eyes of the law by making particular conduct [i.e., deviate sexual intercourse between persons of the ‘same sex’]—and only that conduct—subject to criminal sanction.”140 That the Justices in the majority reflexively moved back and forth between the sex-based classification and the affected class of “homosexuals” without any explanation suggests how pervasively our society, our language, and our constitutional culture assume that homosexuality is relational and is relational because of sex.

Exactly ten years after Lawrence, the Court struck down Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in United States v. Windsor.141 The challenged provision provided that “the word ‘marriage’ means only a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife, and the word ‘spouse’ refers only to a person of the opposite sex who is a husband or a wife.”142 Nowhere does the DOMA text mention discrimination or exclusion because of sexual orientation; the DOMA discriminations and exclusions are solely because of sex (or, more precisely, the sex of the two putative spouses). Yet the Court’s analysis began, and pretty much ended, with the finding that Congress passed the law to express “both moral disapproval of homosexuality, and a moral conviction that heterosexuality better comports with traditional (especially Judeo–Christian) morality.”143 As before, the Court did not require any explanation as to why a sex-based bar should be treated as a law discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation. Even the no-holds-barred dissenting opinion did not challenge this obvious point.

State marriage equality litigation addressed the sex discrimination argument for gay rights more directly. Almost half of states have constitutional ERAs.144 The Supreme Court of Hawaii in Baehr v. Lewin145 famously ruled that the state constitutional bar to discrimination because of sex required the state to demonstrate a compelling justification for its same-sex marriage bar. Hawaii’s Constitutional Convention, convened in 1978, understood that a bar to sex discrimination not only protects women but also protects lesbians and gay men.146 Hawaii’s constitutional framers as well as its justices understood antigay discrimination itself as relational: when an institution discriminates against a lesbian, it is doing so because of the sex of her preferred romantic partner, the object of her desire.

Baehr has been criticized as well as praised, and most judges—including those who have ruled in favor of marriage equality—have been reluctant to address the Loving analogy for gay marriage, even as others have embraced it.147 Some judges have explicitly rejected the argument. In a leading case, California Chief Justice Ron George interpreted the state constitution to invalidate the same-sex marriage exclusion. His opinion for the court applied heightened scrutiny for two reasons: the exclusion of same-sex couples was both a denial of the fundamental right to marry and an exclusion from marital benefits and duties because of a suspect classification, namely, sexual orientation. Although three of the seven justices found the Loving analogy persuasive as applied to sex discrimination as well, the chief justice (and the controlling vote) rejected it explicitly.148 Why should gay rights and marriage equality piggyback on the advances made by women for sex equality?

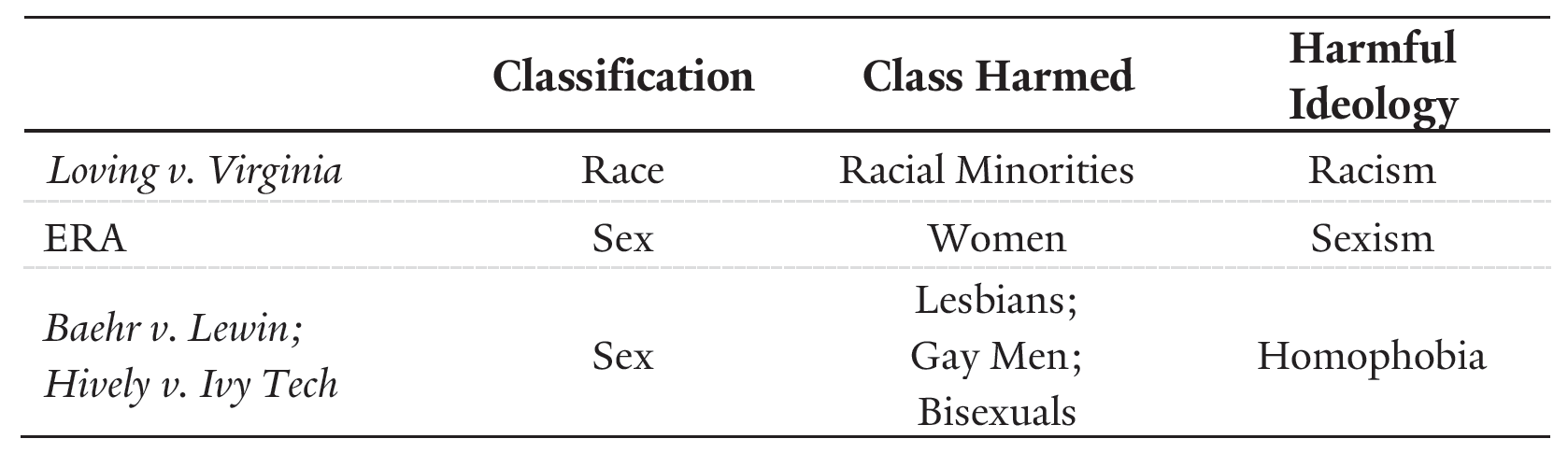

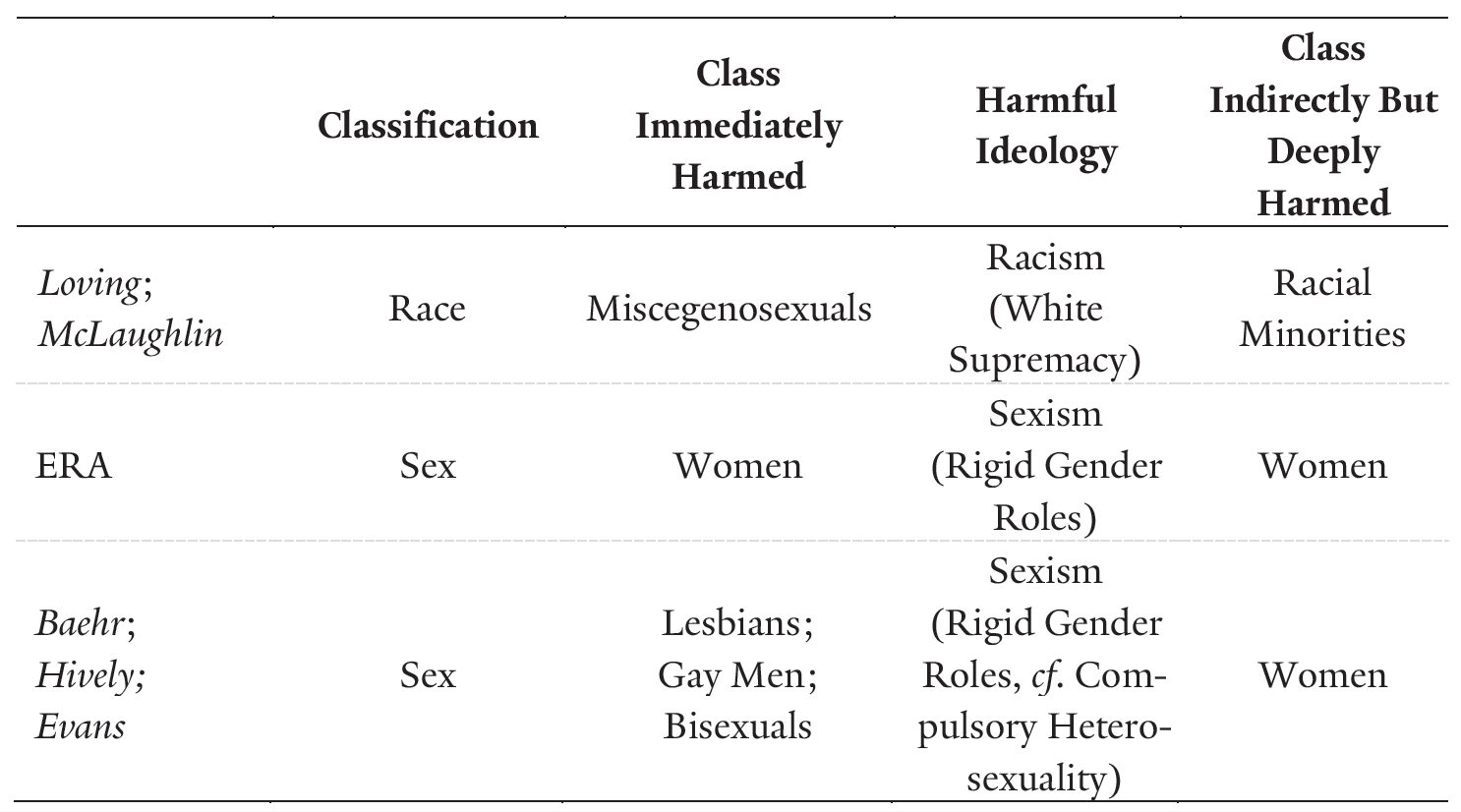

Chief Justice George’s opinion dovetails with Judge Sykes’s objection to the Loving analogy. The table below explains why lawyers and judges have traditionally not accepted the sex discrimination argument for gay rights: there is a lack of symmetry among the classification, the class that is harmed, and the harmful ideology that the antidiscrimination rule would reject.

table 1.

why some judges do not accept the loving analogy for lgbt rights

Lawyers love symmetry. The foregoing table disturbs them. Nonlawyers like simple, intuitive rules. Occam’s razor cuts against the Loving analogy for many intelligent Americans.

The precepts of symmetry and simplicity underwrite Judge Sykes’s Hively dissent, the Justice Department’s Zarda brief, and, most likely, the Eleventh Circuit’s majority opinion in Evans. The lack of symmetry among the classification, class, and ideology targeted for regulation might explain why a number of bills and statutes have prohibited both sex and sexual orientation (as well as gender identity) discrimination: they are different categories, protect different classes of Americans, and regulate different ideologies (sexism versus homophobia). And, as Judges Sykes and Pryor argue, this also explains why in ordinary parlance sex discrimination is not immediately mentioned when a gay person is being excluded.

Is this a decisive objection to the relational discrimination arguments—and hence to the opinions of Chief Judge Wood and Judge Flaum? Again, the legislative record is instructive. As congressional committees noted in their PDA reports, some states had bars to both sex and pregnancy discrimination.149 Perhaps Gilbert could have been justified, as a matter of text-based interpretation, by this contrast. It is clear from the reports, however, that the PDA Congress did not think this was a valid justification.150

Judges Frank Easterbrook and Kenneth Ripple, no easy votes for a job discrimination plaintiff, joined the Hively majority opinion. So, judges strongly committed to text-based, rule-of-law values can agree with Chief Judge Wood. In such cases, the statutory interpreter needs to dig more deeply. Like Judge Rosenbaum in the Eleventh Circuit and Judge Rovner, who authored the original panel opinion in Hively,151 I also want to think about the issue from another angle, namely, the purpose of Title VII to free workers of gender stereotypes.

B. Sex as Gender: Homophobia as Prescriptive Sex Stereotyping

Although I am inclined to see the issue as the Seventh Circuit majority did, there is room for debate about the application of the statutory language to the facts of Hively and Evans. In such instances, interpreters routinely consult statutory purpose to derive principles that might resolve—or suggest—a statutory ambiguity.152 As with the text, Title VII’s overall purpose—the merit-based workplace with respect to race, color, national origin, religion, and sex—has filled out over time and enjoyed a complicated interplay with constitutional discourse. Title VII has been authoritatively, and repeatedly, interpreted to regulate employer gender stereotyping. Congress has endorsed, in both statutory text and vast legislative deliberations, the notion that discrimination because of sex includes employer policies that impose gender-based norms onto male and female employees alike. The merit-based workplace entrenched by Title VII reflects a statutory purpose to protect workers against being penalized because of gender-based stereotypes. Sex-stereotyping claims are ones that affect male and female employees equally, and this understanding of the statutory purpose provides a way to understand how classification, class, and harmful ideology reconnect in Title VII cases involving LGBT claimants.

1. The 1964 Act and the 1972 Amendments