How Qualified Immunity Fails

abstract. This Article reports the findings of the largest and most comprehensive study to date of the role qualified immunity plays in constitutional litigation. Qualified immunity shields government officials from constitutional claims for money damages so long as the officials did not violate clearly established law. The Supreme Court has described the doctrine as incredibly strong—protecting “all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law.” Legal scholars and commentators describe qualified immunity in equally stark terms, often criticizing the doctrine for closing the courthouse doors to plaintiffs whose rights have been violated. The Court has repeatedly explained that qualified immunity must be as powerful as it is to protect government officials from burdens associated with participating in discovery and trial. Yet the Supreme Court has relied on no empirical evidence to support its assertion that qualified immunity doctrine shields government officials from these assumed burdens.

This Article is the first to test this foundational assumption underlying the Supreme Court’s qualified immunity decisions. I reviewed the dockets of 1,183 Section 1983 cases filed against state and local law enforcement defendants in five federal court districts over a two-year period and measured the frequency with which qualified immunity motions were brought by defendants, granted by courts, and dispositive before discovery and trial. I found that qualified immunity rarely served its intended role as a shield from discovery and trial in these cases. Across the five districts in my study, just thirty-eight (3.9%) of the 979 cases in which qualified immunity could be raised were dismissed on qualified immunity grounds. And when one considers all the Section 1983 cases brought against law enforcement defendants—each of which could expose law enforcement officials to burdens associated with discovery and trial—just seven (0.6%) were dismissed at the motion to dismiss stage and thirty-one (2.6%) were dismissed at summary judgment on qualified immunity grounds. My findings enrich our understanding of qualified immunity’s role in constitutional litigation, belie expectations about the policy interests served by qualified immunity, and show that qualified immunity doctrine should be modified to reflect its actual role in constitutional litigation.

author. Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law. For helpful conversations and comments, thanks to Will Baude, Karen Blum, Alan Chen, Beth Colgan, Richard Fallon, William Hubbard, Aziz Huq, John Jeffries, Justin Murray, Doug NeJaime, James Pfander, John Rappaport, Alexander Reinert, Louis Michael Seidman, Stephen Yeazell, and participants in workshops at The University of Chicago Law School, Duke University School of Law, Harvard Law School, and UCLA School of Law. Special thanks to Benjamin Nyblade, who calculated the statistical significance of my findings. Thanks also to Michelle Cuozzo, David Koller, Rosemary McClure, David Schmutzer, and the expert research staff at UCLA’s Hugh & Hazel Darling Law Library for excellent research assistance, and thanks to R. Henry Weaver, Arjun Ramamurti, Kyle Edwards, Kyle Victor, Erin van Wesenbeeck, and the editors of the Yale Law Journal for excellent editorial assistance.

This Article's dataset is available at: https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.sbcc2fr3w.

Introduction

The United States Supreme Court appears to be on a mission to

curb civil rights lawsuits against law enforcement officers, and appears to believe

qualified immunity is the means of achieving its goal. The Supreme Court has

long described qualified immunity doctrine as robust—protecting “all but the

plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law.”1 And the Court’s most recent

qualified immunity decisions have broadened the scope of the doctrine even further.2 The Court has also granted a rash of

petitions for certiorari in cases in which lower courts denied qualified immunity

to law enforcement officers, reversing or vacating every one.3 In these decisions, the Supreme

Court has scolded lower courts for applying qualified immunity doctrine in a

manner that is too favorable to plaintiffs and thus ignores the “importance of

qualified immunity ‘to society as a whole.’”4 As Noah Feldman has

observed, the Supreme Court’s recent qualified immunity decisions have sent a

clear message to lower courts: “The Supreme Court wants fewer lawsuits against

police to go

forward.”5 And the Court believes that

qualified immunity doctrine is the way to keep the doors to the courthouse

closed.

Among legal scholars and other commentators, there is a widespread belief that the Supreme Court is succeeding in its efforts. Scholars report that qualified immunity motions are raised frequently by defendants, are granted frequently by courts, and often result in the dismissal of cases.6 As Ninth Circuit Judge Stephen Reinhardt has written, the Supreme Court’s recent qualified immunity decisions have “created such powerful shields for law enforcement that people whose rights are violated, even in egregious ways, often lack any means of enforcing those rights.”7 Three of the foremost experts on Section 1983 litigation—Karen Blum, Erwin Chemerinsky, and Martin Schwartz—have concluded that recent developments in qualified immunity doctrine leave “not much Hope left for plaintiffs.”8

The widespread assumption that qualified immunity provides powerful protection for government officials belies how little we know about the role qualified immunity plays in the litigation of constitutional claims.9 The scant evidence available on this topic points in opposite directions. Studies of qualified immunity decisions have found that qualified immunity motions are infrequently denied, suggesting that the doctrine plays a controlling role in the resolution of many Section 1983 cases.10 But when Alexander Reinert studied the dockets in Bivens actions—constitutional cases brought against federal actors—he found that grants of qualified immunity led to just 2% of case dismissals over a three-year period.11 If qualified immunity protects all but the “plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law,”12 and qualified immunity motions are infrequently denied, how can qualified immunity be the basis for dismissal of such a small percentage of cases?

More than descriptive accuracy is at stake in answering this question—it goes to a core justification for qualified immunity’s existence. Although the concept of qualified immunity was drawn from defenses existing in the common law at the time 42 U.S.C. § 1983 was enacted, the Court has made clear that the contours of qualified immunity’s protections are shaped not by the common law but instead by policy considerations.13 In particular, the Court seeks to balance “two important interests—the need to hold public officials accountable when they exercise power irresponsibly and the need to shield officials from harassment, distraction, and liability when they perform their duties reasonably.”14 Since the doctrine’s inception, the Court has repeatedly stated that financial liability is one of the burdens qualified immunity is intended to protect against.15 Yet, as I showed in a prior study, law enforcement defendants are almost always indemnified and thus rarely pay anything towards settlements and judgments entered against them.16 Near certain and universal indemnification drastically reduces the value of qualified immunity as a protection against the burden of financial liability.

In recent years, the Court has focused increasingly on a different justification for qualified immunity: the need to protect government officials from nonfinancial burdens associated with discovery and trial.17 This desire has arguably shaped qualified immunity more than any other policy justification for the doctrine.18 Yet we do not know to what extent discovery and trial burden government officials, or the extent to which qualified immunity doctrine protects against those assumed burdens. Although both questions demand critical investigation, this Article focuses on the latter. Assuming that discovery and trial do impose substantial burdens on government officials, and that shielding officials from discovery and trial is a legitimate aim of qualified immunity doctrine, to what extent does qualified immunity actually achieve its intended goal?

To answer these questions, I undertook the largest and most comprehensive study to date of the role qualified immunity plays in constitutional litigation. I reviewed the dockets of 1,183 lawsuits filed against state and local law enforcement defendants over a two-year period in five federal district courts—the Southern District of Texas, the Middle District of Florida, the Northern District of Ohio, the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, and the Northern District of California.19 I tracked several characteristics of these cases including the frequency with which qualified immunity was raised, the stage of the litigation at which qualified immunity was raised, the courts’ assessments of defendants’ qualified immunity motions, the frequency and outcome of interlocutory and final appeals of qualified immunity decisions, and the cases’ dispositions.

I found that, contrary to judicial and scholarly assumptions, qualified immunity is rarely the formal reason that civil rights damages actions against law enforcement end. Qualified immunity is raised infrequently before discovery begins: across the districts in my study, defendants raised qualified immunity in motions to dismiss in 13.9% of the cases in which they could raise the defense.20 These motions were less frequently granted than one might expect: courts granted motions to dismiss in whole or part on qualified immunity grounds 13.6% of the time.21 Qualified immunity was raised more often by defendants at summary judgment and was more often granted by courts at that stage. But even when courts granted motions to dismiss and summary judgment motions on qualified immunity grounds, those grants did not always result in the dismissal of the cases—additional claims or defendants regularly remained and continued to expose government officials to the possibility of discovery and trial. Across the five districts in my study, just 3.9% of the cases in which qualified immunity could be raised were dismissed on qualified immunity grounds.22 And when one considers all the Section 1983 cases brought against law enforcement defendants—each of which could expose law enforcement officials to whatever burdens are associated with discovery and trial—just 0.6% of cases were dismissed at the motion to dismiss stage and 2.6% were dismissed at summary judgment on qualified immunity grounds.23

Although courts rarely dismiss Section 1983 suits against law enforcement on qualified immunity grounds, there is every reason to believe that qualified immunity doctrine influences the litigation of Section 1983 claims in other ways. The threat of a qualified immunity motion may cause a person never to file suit, or to settle or withdraw her claims before discovery or trial.24 Qualified immunity motion practice and interlocutory appeals of qualified immunity denials may increase the costs and delays associated with Section 1983 litigation. The challenges of qualified immunity doctrine may cause plaintiffs’ attorneys to include claims in their cases that cannot be dismissed on qualified immunity grounds—claims against municipalities, claims seeking injunctive relief, and state law claims. Qualified immunity likely influences the litigation of cases against law enforcement in each of these ways. But, as my study makes clear, qualified immunity does not affect constitutional litigation against law enforcement in the way the Court expects and intends.

One should not conclude based on my findings that the Supreme Court simply needs to make qualified immunity stronger. As a preliminary matter, qualified immunity may not be well suited to weed out only insubstantial cases.25 Moreover, my data suggest that qualified immunity is often fundamentally ill suited to dismiss filed cases, regardless of their underlying merits.26 Although district courts recognize that they should dispose of cases as early as possible on qualified immunity grounds, plaintiffs can often plausibly plead clearly established constitutional violations and thus defeat motions to dismiss. Factual disputes regularly prevent dismissal at summary judgment. And even when courts grant qualified immunity motions, additional defendants or claims often remain that continue to expose government officials to the burdens of litigation. My data also suggest that qualified immunity is less essential than has been assumed to serve its intended protective function. The Supreme Court suggests in its opinions that qualified immunity is the only barrier standing between government officials and the burdens of discovery and trial. Instead, my study shows that litigants and courts have a wide range of tools at their disposal to resolve Section 1983 cases.

One also should not conclude based on my findings that qualified immunity is more benign than has been assumed. My findings do show that Section 1983 claims against the police are infrequently dismissed on qualified immunity grounds. But qualified immunity doctrine has been roundly criticized as incoherent, illogical, and overly protective of government officials who act unconstitutionally and in bad faith.27 The fact that few cases are dismissed on qualified immunity grounds does not fundamentally undermine these critiques.

Qualified immunity doctrine is intended by the Court to balance “the need to hold government officials accountable when they exercise power irresponsibly and the need to shield officials from harassment, distraction, and liability when they perform their duties responsibly.”28 Were qualified immunity reliably insulating government officials from the burdens of litigation in insubstantial cases, one could argue that the doctrine’s incoherence, illogic, and overprotection of government officials were unfortunate but necessary to further government interests. Yet available evidence suggests that qualified immunity is not achieving its policy objectives; the doctrine is unnecessary to protect government officials from financial liability and ill suited to shield government officials from discovery and trial in most filed cases. Qualified immunity may, in fact, increase the costs and delays associated with constitutional litigation. Qualified immunity might benefit the government in other ways, and further research is necessary to explore this possibility.29 But the evidence now available weakens the Court’s current justifications for the doctrine’s structure and highly restrictive standards. The Supreme Court has written that evidence undermining its assumptions about the realities of constitutional litigation might “justify reconsideration of the balance struck” in its qualified immunity decisions.30 Given my findings, it is high time for the Supreme Court to reconsider that balance.

The remainder of the Article proceeds as follows. Part I describes the Supreme Court’s assumptions about the burdens of discovery and trial for government officials, and the ways in which these assumptions have shaped qualified immunity doctrine. In Part II, I describe the methodology of my study. In Part III, I set forth my findings about the frequency with which law enforcement defendants raise qualified immunity, the frequency with which courts grant qualified immunity, the frequency and outcome of qualified immunity interlocutory and final appeals, and the frequency with which qualified immunity disposes of plaintiffs’ cases. In Part IV, I consider the implications of my findings for descriptive accounts of qualified immunity’s role in constitutional litigation and expectations about the policy interests served by qualified immunity doctrine. I also suggest adjustments to qualified immunity that would create more consistency between the doctrine and its actual role in constitutional litigation.

I. qualified immunity’s expected role in constitutional litigation

The Supreme Court has long viewed qualified immunity as a means of protecting government officials from burdens associated with participating in discovery and trial in insubstantial cases. Indeed, the Supreme Court has justified several major developments in qualified immunity doctrine over the past thirty-five years as means of protecting government officials from these assumed burdens. In this Part, I describe the Court’s stated assumptions about the purposes served by qualified immunity, the ways in which those assumptions have shaped qualified immunity doctrine, and the lack of evidence supporting the Court’s concerns and interventions.

A. The Court’s Concerns About the Burdens of Litigation

The Supreme Court has made clear that its qualified immunity jurisprudence reflects the Court’s view about how best to balance “the importance of a damages remedy to protect the rights of citizens” against “the need to protect officials who are required to exercise their discretion and the related public interest in encouraging the vigorous exercise of official authority.”31 Yet the Court’s descriptions of the ways in which qualified immunity protects government officials have shifted over time.

The Supreme Court’s original rationale for qualified immunity was to shield officials from financial liability. The Court first announced that law enforcement officials were entitled to a qualified immunity from suits in the 1967 case of Pierson v. Ray.32 That decision justified qualified immunity as a means of protecting government defendants from financial burdens when acting in good faith in legally murky areas.33 Qualified immunity was necessary, according to the Court, because “[a] policeman’s lot is not so unhappy that he must choose between being charged with dereliction of duty if he does not arrest when he had probable cause, and being mulcted in damages if he does.”34 The scope of the qualified immunity defense is in many ways consistent with an interest in protecting government officials from financial liability. For example, qualified immunity does not attach in claims against municipalities, claims against some private actors, and claims for injunctive or declaratory relief.35 Indeed, the Court has been clear that municipalities and private prison guards are not entitled to qualified immunity in part because neither type of defendant is threatened by personal financial liability.36

The Supreme Court’s decision in Harlow v. Fitzgerald, fifteen years after Pierson, expanded the policy goals animating qualified immunity. The Court explained in Harlow that qualified immunity was necessary not only to protect government officials from financial liability, but also to protect against “the diversion of official energy from pressing public issues,” “the deterrence of able citizens from acceptance of public office,” and “the danger that fear of being sued will ‘dampen the ardor of all but the most resolute, or the most irresponsible [public officials], in the unflinching discharge of their duties.’”37

In subsequent cases, the Court has focused increasingly on the need to protect government officials from burdens associated with discovery and trial, with the expectation that qualified immunity can protect government officials from those burdens. In Mitchell v. Forsyth, the Court reaffirmed the Harlow Court’s conclusion that qualified immunity was necessary to protect against the burdens associated with both trial and pretrial matters, like discovery, because “‘[i]nquiries of this kind can be peculiarly disruptive of effective government.’”38 In Ashcroft v. Iqbal, the Court again emphasized the value of qualified immunity in curtailing the time-intensive discovery process. As the Court explained:

The basic thrust of the qualified-immunity doctrine is to free officials from the concerns of litigation, including “avoidance of disruptive discovery.” There are serious and legitimate reasons for this. If a Government official is to devote time to his or her duties, and to the formulation of sound and responsible policies, it is counterproductive to require the substantial diversion that is attendant to participating in litigation and making informed decisions as to how it should proceed. Litigation, though necessary to ensure that officials comply with the law, exacts heavy costs in terms of efficiency and expenditure of valuable time and resources that might otherwise be directed to the proper execution of the work of the Government.39

In recent years, the interest in shielding government officials from the burdens of discovery and trial has taken center stage in the Court’s qualified immunity calculations. In 1997, the Supreme Court made clear that “the risk of ‘distraction’ alone cannot be sufficient grounds for an immunity.”40 Twelve years later, in 2009, the Court described protecting government officials from burdens associated with discovery and trial as the “‘driving force’ behind [the] creation of the qualified immunity doctrine.”41

The Court’s interest in protecting government officers from burdens associated with discovery and trial extends not only to defendants but to other government officials who may be required to testify, respond to discovery, or otherwise participate in litigation. In Filarsky v. Delia, the Court held that a private actor retained by the government to carry out its work was entitled to qualified immunity in part because the “distraction of lawsuits . . . will also often affect any public employees with whom they work by embroiling those employees in litigation.”42

B. Doctrinal Impact of the Court’s Desire To Protect Defendants from Discovery and Trial

Over the past thirty-five years, the Court’s interest in protecting government officials from discovery and trial has shaped qualified immunity in several important ways. Granted, some aspects of qualified immunity doctrine are inconsistent with the Court’s interest in protecting government officials from discovery and trial. After all, government officials must participate in discovery and trial in claims against municipalities—as witnesses, if not as defendants. In addition, government officials must participate in discovery and trial in claims for declaratory and injunctive relief. Yet, in the years since Pierson, the Court’s concerns about the burdens of discovery and trial have led the Court to remove the subjective prong of the qualified immunity defense, adjust the process by which lower courts assess qualified immunity motions, and allow interlocutory appeals of qualified immunity denials.

1. Defendants’ State of Mind

The Court’s interest in shielding government defendants from discovery and trial underlay its decision to eliminate the subjective prong of the qualified immunity defense. From 1967, when qualified immunity was first announced by the Supreme Court, until 1982, when Harlow was decided, a defendant seeking qualified immunity had to show both that his conduct was objectively reasonable and that he had a “good-faith” belief that his conduct was proper.43 In Harlow, the Supreme Court concluded that the subjective prong of the defense was “incompatible” with the goals of qualified immunity because an official’s subjective intent often could not be resolved before trial.44 Moreover, during discovery, gathering evidence of an official’s subjective motivation “may entail broad-ranging discovery and the deposing of numerous persons, including an official’s professional colleagues.”45 By eliminating the subjective prong of the qualified immunity analysis, the Court believed it could “avoid ‘subject[ing] government officials either to the costs of trial or to the burdens of broad-reaching discovery’ in cases where the legal norms the officials are alleged to have violated were not clearly established at the time.”46

2. The Order of Battle

The Court’s concerns about burdens associated with litigation also influenced its decisions regarding the manner in which courts should analyze qualified immunity. The Supreme Court believes that lower courts deciding qualified immunity motions are faced with two questions—whether a constitutional right was violated, and whether that right was clearly established. But the Court has wavered in its view regarding the order in which these questions must be answered—what is often referred to as “the order of battle.” In 2001, the Supreme Court held in Saucier v. Katz that a court engaging in a qualified immunity analysis must first decide whether the defendant violated the plaintiff’s constitutional rights and then decide whether the constitutional right was clearly established.47 The Court insisted on this sequence because it would allow “the law’s elaboration from case to case . . . . The law might be deprived of this explanation were a court simply to skip ahead to the question whether the law clearly established that the officer’s conduct was unlawful in the circumstances of the case.”48

Eight years later, in Pearson v. Callahan, the Court reversed itself and concluded that Saucier’s two-step process was not mandatory.49In reaching this conclusion, Justice Alito, writing for the Court, relied heavily on the fact that courts considered the process mandated by Saucier to be unduly burdensome.50 Justice Alito also explained that the process wasted the parties’ resources, writing that “Saucier’s two-step protocol ‘disserve[s] the purpose of qualified immunity’ when it ‘forces the parties to endure additional burdens of suit—such as the costs of litigating constitutional questions and delays attributable to resolving them—when the suit otherwise could be disposed of more readily.’”51 Concerns about the burdens of litigation therefore led the Court to allow lower courts not to decide the first question—whether the conduct was unconstitutional—if they could grant the motion on the ground that the right was not clearly established.

3. Interlocutory Appeals

The Court’s interest in protecting government officials from the burdens of discovery and trial also motivated its decision to allow interlocutory appeals of qualified immunity denials.52 Generally speaking, litigants in federal court can only appeal final judgments; interlocutory appeals are not allowed unless a right “cannot be effectively vindicated after the trial has occurred.”53 The question decided by the Court in Mitchell v. Forsyth was whether qualified immunity should be understood as an entitlement not to stand trial that cannot be remedied by an appeal at the end of the case. In concluding that a denial of qualified immunity could be appealed immediately, the Court relied on its assertion in Harlow that qualified immunity was “an entitlement not to stand trial or face the other burdens of litigation.”54 If qualified immunity protected only against the financial burdens of liability, there would be no need for interlocutory appeal; defendants denied qualified immunity could appeal after a final judgment and before the payment of any award to a plaintiff. Instead, the Court concluded, qualified immunity “is an immunity from suit rather than a mere defense to liability; and . . . it is effectively lost if a case is erroneously permitted to go to trial.”55 Only an interest in protecting officials from discovery and trial can justify this holding.

C. The Lack of Empirical Support for the Court’s Concerns and Interventions

The Supreme Court’s qualified immunity decisions over the past thirty-five years have relied on the assumptions that discovery and trial impose substantial burdens on government officials, and that qualified immunity can shield government officials from these burdens. Four years after it decided Harlow, the Court asserted that the decision had achieved the Court’s goal of facilitating dismissal at summary judgment.56 In subsequent years, the Court’s repeated invocation of the burdens of discovery and trial, and repeated reliance on qualified immunity doctrine to protect defendants from those assumed burdens, suggest the Court’s continued faith in these positions. Yet the Court has relied on no empirical evidence to support its views.

Scholars have decried the lack of empirical evidence about the realities of civil rights litigation relevant to questions about the proper scope of qualified immunity doctrine and the extent to which the doctrine achieves its intended purposes. Twenty years ago, Alan Chen complained that the Court and its critics make assertions about the role of qualified immunity in constitutional litigation without evidence to support their claims.57 Although scholars have empirically examined some questions about qualified immunity—paying particular attention to the impact of Pearson on the development of constitutional law—the same is largely true today.58 As Richard Fallon has observed, “[W]e could make far better judgments of how well qualified immunity serves the function of getting the right balance between deterrence of constitutional violations and chill of conscientious official action if we had better empirical information.”59This Article, and my research more generally, aims to fill that gap.

II. study methodology

To evaluate the role that qualified immunity plays in the litigation of Section 1983 suits, I reviewed the dockets of cases filed from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2012 in five districts: the Southern District of Texas, Middle District of Florida, Northern District of Ohio, Eastern District of Pennsylvania, and Northern District of California. Several considerations led me to study these five districts.

I chose to look at decisions from district courts in the Third, Fifth, Sixth, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuits because I expected that judges from these circuits might differ in their approach to qualified immunity and to Section 1983 litigation more generally. This expectation was based on my review of district court qualified immunity decisions from each of the circuits, as well as a view, shared by others, that judges in these circuits range from conservative to more liberal.60 Moreover, commentators believe that courts in these circuits vary in their approach to qualified immunity, with judges in the Third and Ninth Circuits favoring plaintiffs, and judges in the Eleventh Circuit so hostile to Section 1983 cases that they are described as applying “unqualified immunity.”61

I chose these five districts within these five circuits for two reasons. First, I expected that these five districts would have a large number of cases to review: from 2011 to 2012, these districts were among the busiest in the country, as measured by case filings.62 Second, these five districts have a range of small, medium, and large law enforcement agencies and agencies of comparable sizes.63

I chose to review dockets instead of relying on the most obvious alternative—decisions available on Westlaw.64 Although Westlaw can quickly sort out decisions in which qualified immunity is addressed by district courts, Westlaw could not capture information essential to my analysis about the frequency with which qualified immunity protects government officials from discovery and trial. First, a Westlaw search could capture no information about the number of cases in which qualified immunity was never raised. In addition, a Westlaw search could not capture information about the number of cases in which qualified immunity was raised by the defendant in his motion but was not addressed by the court in its decision. Even when a defendant raises a qualified immunity defense and the district court addresses qualified immunity in its decision, the decision may not appear on Westlaw—Westlaw does not capture motions resolved without a written opinion, and includes only those opinions that are selected to appear on the service.65 In other words, opinions on Westlaw can offer insights about the ways in which district courts assess qualified immunity when they choose to address the issue in a written opinion and the opinion is accessible on Westlaw, but can say little about the frequency with which qualified immunity is raised, the manner in which all motions raising qualified immunity are decided, and the impact of qualified immunity on case dispositions.

I reviewed the dockets of cases filed in 2011 and 2012 in the five districts in my study.66 I searched case filings in the five districts in my study through Bloomberg Law, an online service that has dockets otherwise available through PACER and additionally provides access to documents submitted to the court—complaints, motions, orders, and other papers.67 Within Bloomberg Law, I limited my search to those cases that plaintiffs had designated under the broad term “Other Civil Rights,” nature-of-suit code 440.68 This search generated 462 dockets in the Southern District of Texas, 465 dockets in the Northern District of Ohio, 674 dockets in the Middle District of Florida, 712 dockets in the Northern District of California, and 1,435 dockets in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. I reviewed the complaints associated with these 3,748 dockets and included in my dataset those cases, brought by civilians, alleging constitutional violations by state and local law enforcement agencies and their employees.69

I limited my study to cases brought by civilians against law enforcement defendants for several reasons. First, many of the Supreme Court’s qualified immunity decisions have involved cases brought against law enforcement. Of the twenty-nine qualified immunity cases that the Supreme Court has decided since 1982, almost half have involved constitutional claims against state and local law enforcement.70 Because the Court has developed qualified immunity doctrine (and articulated its underlying purposes) primarily in cases involving law enforcement, it makes sense to examine whether the doctrine is meeting its express goals in these types of cases.

Limiting my study to Section 1983 cases against state and local law enforcement also creates some substantive consistency across the cases in my dataset. Most Section 1983 cases against state and local law enforcement allege Fourth Amendment violations—excessive force, false arrest, and wrongful searches—and, less frequently, First and Fourteenth Amendment violations. Restricting my study to suits by civilians against state and local law enforcement facilitates direct comparison of outcomes in similar cases across the five districts in my study. Finally, much of my own prior research has focused on lawsuits against state and local law enforcement, and maintaining this focus here allows for future synthesis of my findings.71

The resulting dataset includes a total of 1,183 cases from these five districts: 131 cases from the Southern District of Texas, 225 cases from the Middle District of Florida, 172 cases from the Northern District of Ohio, 248 cases from the Northern District of California, and 407 cases from the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. For each of these dockets, I tracked multiple pieces of information relevant to this study, including whether the plaintiff(s) sued individual officers and/or the municipality, the relief sought by the plaintiff(s), whether the law enforcement defendant(s) filed one or more motions to dismiss on the pleadings or for summary judgment, whether and when the defendant(s) raised qualified immunity, how the court decided the motions raised by the defendant(s), whether there was an interlocutory or final appeal of a qualified immunity decision, and how the case was ultimately resolved.72 Although some of this information was available from the docket sheet, I obtained much of the information by reading motions and opinions linked to the dockets on Bloomberg Law.

Although some of my coding decisions were straightforward, others involved less obvious choices. Because my coding decisions may make most sense when reviewed in context, I have described those decisions in detail in the footnotes accompanying the data.73 Throughout, my coding decisions were guided by my focus on the role that qualified immunity played in the resolution of cases and the frequency with which the doctrine meets its goal of shielding government officials from discovery and trial.

My dataset is comprehensive in the five chosen districts. It includes most—if not all—Section 1983 cases filed by civilians against state and local law enforcement in these federal districts over a two-year period, and it offers insights about how frequently qualified immunity is raised in these cases, how courts decide these motions, and how the cases are resolved. There are, however, several limitations of the data. First, although I selected these five districts in part to capture regional variation, they may not represent the full range of court and litigant behavior nationwide. The marked differences in my data across districts do, however, suggest a considerable degree of regional variation. Second, the data offer no information about the role of qualified immunity in state court litigation. This is in part because Bloomberg Law does not offer much information about the litigation of constitutional cases in state courts.74

Third, although this study sheds light on the litigation of constitutional claims against state and local law enforcement officers, it does not necessarily describe the role qualified immunity plays in the litigation of constitutional claims against other types of government employees. It may be that the types of constitutional claims often raised in cases against law enforcement—Fourth Amendment claims alleging excessive force, unlawful arrests, and improper searches—are particularly difficult to resolve on qualified immunity grounds in advance of trial. Fourth Amendment claims may be comparatively easy to plead in a plausible manner (and so could survive a motion to dismiss), and such claims may be particularly prone to factual disputes (making resolution at summary judgment difficult). If so, perhaps qualified immunity motions in cases raising other types of claims would be more successful. On the other hand, John Jeffries has argued that it may be particularly difficult to clearly establish that a use of force violates the Fourth Amendment because Fourth Amendment analysis requires a fact-specific inquiry about the nature of the force used and the threat posed by the person against whom force was used, viewed from the perspective of an officer on the scene.75Further research should explore whether qualified immunity plays a different role in cases brought against other government actors, or cases alleging different types of constitutional violations.

Fourth, qualified immunity may be influencing the litigation of constitutional claims in ways that cannot be measured through the examination of case dockets.76 For example, my study does not measure how frequently qualified immunity causes people not to file lawsuits. It also does not capture information about the frequency with which plaintiffs’ decisions to settle or withdraw their claims are influenced by the threat of a qualified immunity motion or decision. Exploration of these issues is critical to a complete understanding of the role qualified immunity plays in constitutional litigation. I discuss these issues in more depth in Part IV, and future research should explore these questions.77 Yet this Article illuminates several important aspects of qualified immunity’s role in Section 1983 cases. Moreover, by measuring the frequency with which qualified immunity motions are raised, granted, and dispositive, this Article reveals the extent to which the doctrine functions as the Supreme Court expects and critics fear.

III. findings

The Supreme Court has explained that a goal of qualified immunity is to “avoid ‘subject[ing] government officials either to the costs of trial or to the burdens of broad-reaching discovery’ in cases where the legal norms the officials are alleged to have violated were not clearly established at the time.”78 Logically, qualified immunity will only achieve this goal in a case if four conditions are met.

First, the case must be brought against an individual officer and must seek monetary damages. Qualified immunity is not available for claims against municipalities or claims for noneconomic relief. Second, the defendant must raise the qualified immunity defense early enough in the litigation that it can protect him from discovery or trial. If the defendant seeks to protect himself from discovery, he must raise qualified immunity in a motion to dismiss or a motion for judgment on the pleadings; if a defendant seeks to protect himself from trial, he can raise qualified immunity at the pleadings or at summary judgment.79 Third, for a qualified immunity motion to protect government officials against burdens associated with discovery or trial, the court must grant the motion on qualified immunity grounds.80 Finally, the grant of qualified immunity must completely resolve the case. If qualified immunity is granted for an officer on one claim but not another, that officer will continue to have to participate in the litigation of the case. Even when a grant of qualified immunity results in the dismissal of all claims against a defendant, that defendant may still have to participate in the litigation of claims against other defendants. To be sure, the government official who has been dismissed from the case may no longer feel the same psychological burdens associated with the litigation and may have lesser discovery burdens than he would have had as a defendant. But the grant of qualified immunity will not necessarily shield him from the burdens of participating in discovery and trial.

This Part describes my findings regarding the frequency with which each of these conditions is met. I empirically examine six topics: (1) the number of cases in which qualified immunity can be raised by defendants; (2) the number of cases in which defendants choose to raise qualified immunity; (3) the stage(s) of litigation at which defendants raise qualified immunity; (4) the ways in which district courts decide qualified immunity motions; (5) the frequency and outcome of qualified immunity appeals; and (6) the frequency with which qualified immunity is the reason that a case ends before discovery or trial.

My findings regarding these six topics show that, at least in filed cases, qualified immunity rarely functions as expected. Qualified immunity could not be raised in more than 17% of the cases in my dataset, either because the cases did not name individual defendants or seek monetary damages, or because the cases were dismissed sua sponte by the court before the defendants had an opportunity to answer or otherwise respond. Defendants raised qualified immunity in 37.6% of the cases in my dataset in which the defense could be raised. Defendants were particularly disinclined to raise qualified immunity in motions to dismiss: they did so in only 13.9% of the cases in which they could raise the defense at that stage. Courts granted (in whole or part) less than 18% of the motions that raised a qualified immunity defense. Qualified immunity was the reason for dismissal in just 3.9% of the cases in my dataset in which the defense could be raised, and just 3.2% of all cases in my dataset. The remainder of this Part describes each of these findings in more detail.

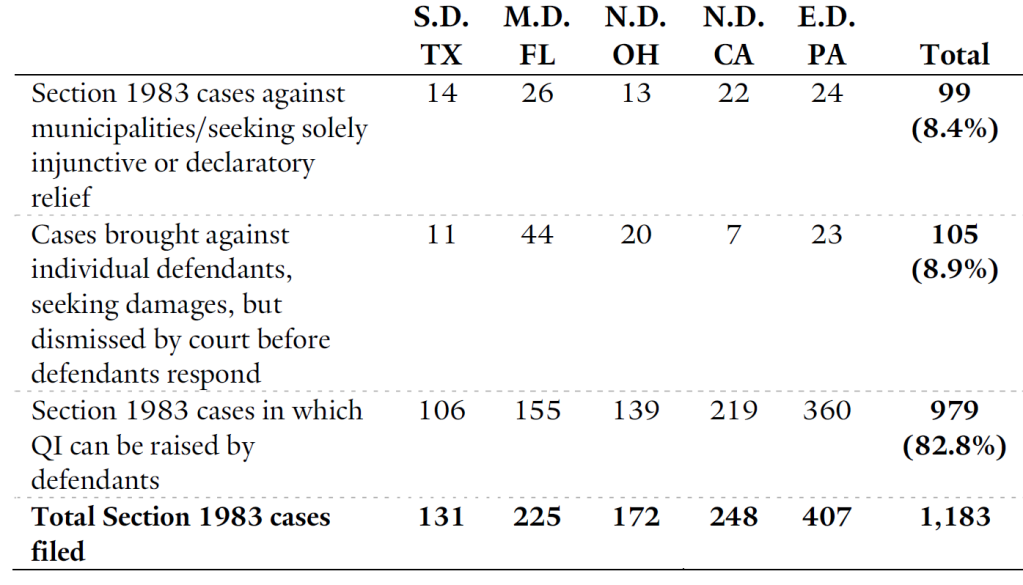

A. Cases in Which Qualified Immunity Cannot Play a Role

There are certain types of cases in which qualified immunity cannot play a role. The Supreme Court has held that qualified immunity does not apply to claims against municipalities and claims for injunctive or declaratory relief.81 Accordingly, qualified immunity cannot protect government officials from discovery or trial in cases asserting only these types of claims. In my docket dataset of 1,183 cases, ninety-nine cases (8.4%) were brought solely against municipalities and/or sought only injunctive or declaratory relief.82

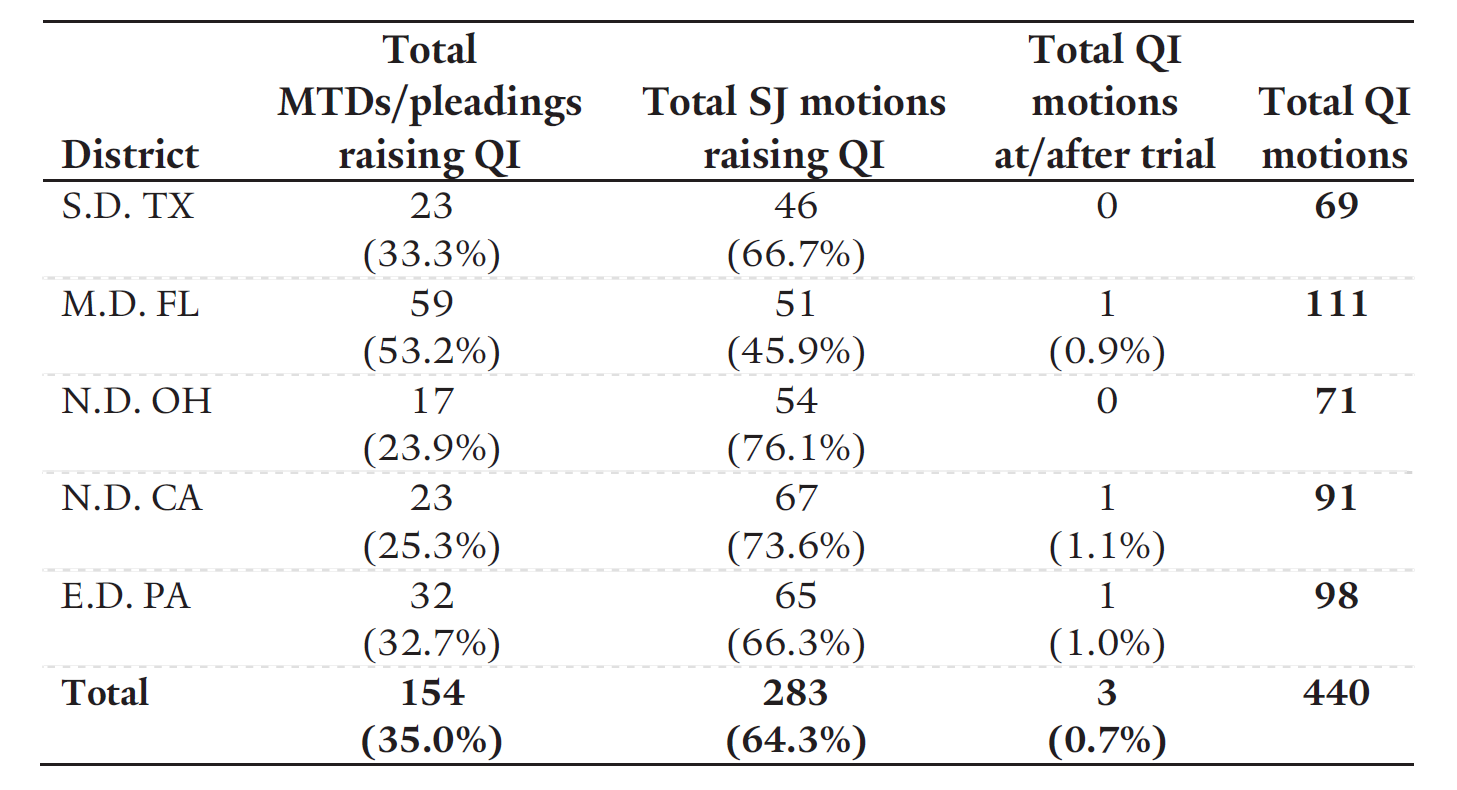

table 1.

frequency with which qualified immunity can be raised, in five districts

Even when cases are brought against individual officers and seek monetary relief, there are some cases in which defendants have no need to raise qualified immunity as a defense—cases dismissed sua sponte by the court before the defendants respond to the complaint. In these cases, qualified immunity is unnecessary to protect defendants from discovery and trial. In the five districts in my docket dataset, 105 (8.9%) complaints naming individual law enforcement officers and seeking damages were dismissed sua sponte by district courts before defendants answered or responded. Most often, district courts dismissed these cases pursuant to their statutory power to review pro se plaintiffs’ complaints and dismiss actions they conclude are frivolous or meritless.83 Other cases were dismissed by the court at this preliminary stage because the plaintiffs never served the defendants or failed to prosecute the case, or because the court remanded the case to state court for lack of subject matter jurisdiction before the defendants were served or responded.

Qualified immunity can only protect government officials from discovery and trial in cases in which government defendants can raise the defense. Defendants could not raise qualified immunity in 8.4% of cases in my docket dataset because those cases did not name individual defendants and/or seek damages. Qualified immunity was unnecessary to shield government officials from discovery or trial in another 8.9% of cases in my dataset because these cases were dismissed by the district courts before defendants could raise the defense. Accordingly, defendants could raise a qualified immunity defense in a total of 979 (82.8%) of the 1,183 complaints filed in the five districts during my two-year study period.

B. Defendants’ Choices: The Frequency and Timing of Qualified Immunity Motions

Qualified immunity can only protect a defendant from the burdens of discovery and trial if she raises the defense in a dispositive motion. Accordingly, this Section examines the frequency with which defendants raise qualified immunity and the stage of litigation at which they raise the defense.84

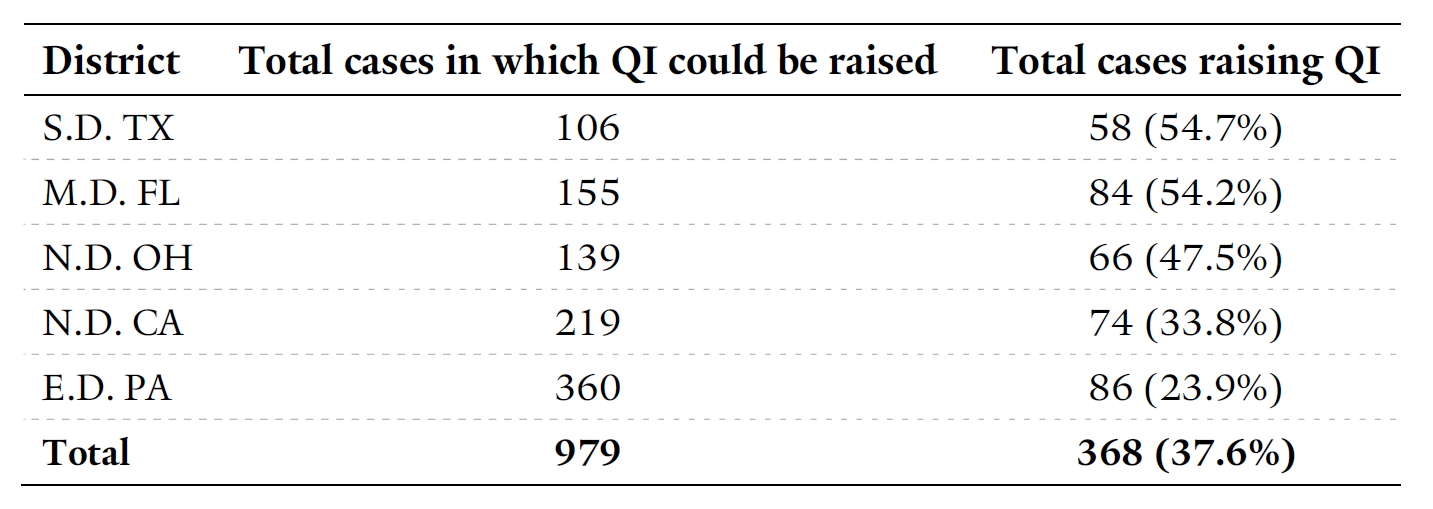

table 2.

frequency with which qualified immunity is raised

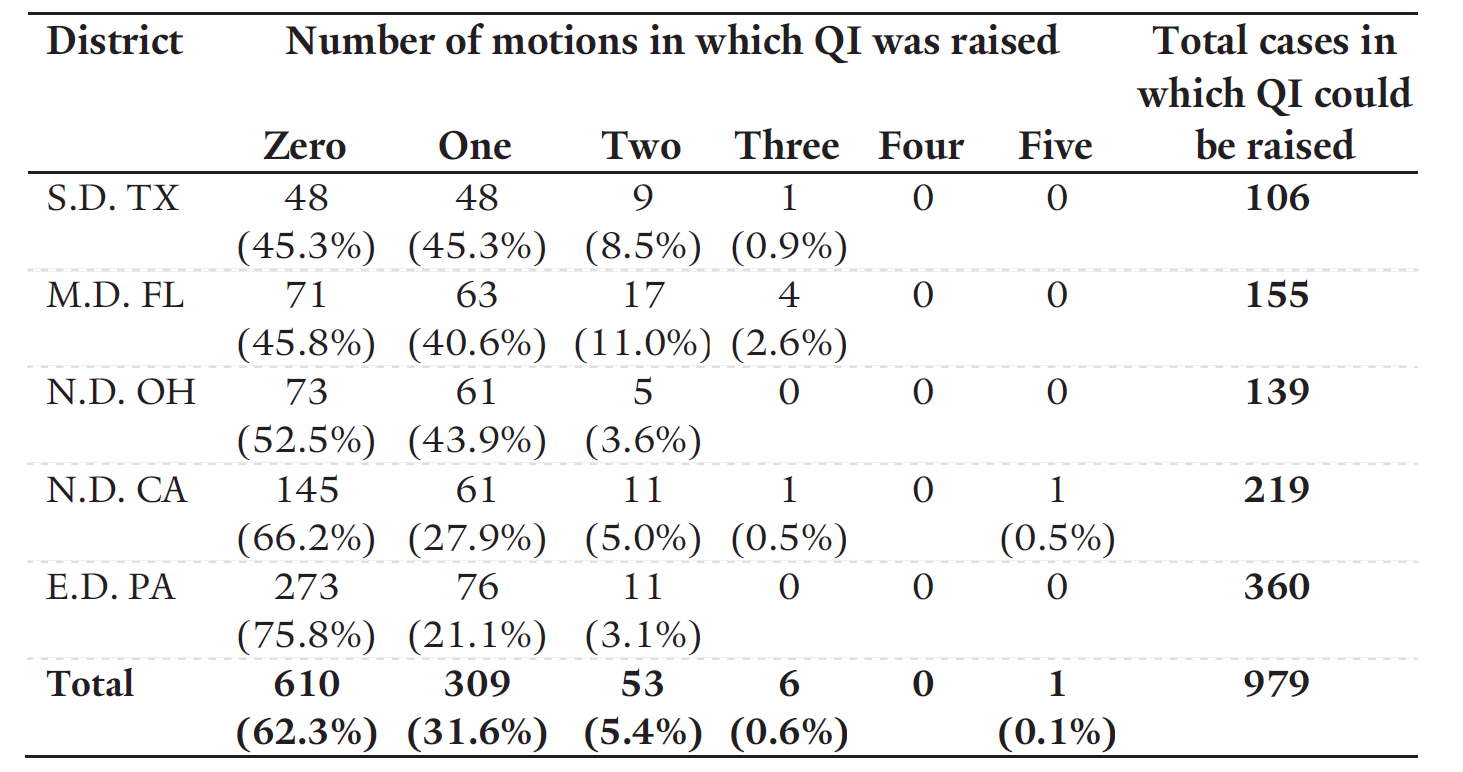

Defendants raised qualified immunity one or more times in 368 (37.6%) of the 979 cases in which defendants could raise the defense. The frequency with which defendants raised qualified immunity varied substantially by district. Defendants in the Southern District of Texas and the Middle District of Florida were most likely to raise the qualified immunity defense; in these districts, defendants brought one or more motions raising qualified immunity in approximately 54% of the cases in which the defense could be raised. Defendants in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania were least likely to raise the qualified immunity defense; defendants brought one or more motions raising qualified immunity in approximately 24% of cases in which the defense could be raised. Defendants in the Northern District of California brought qualified immunity motions in 33.8% of possible cases, and in the Northern District of Ohio defendants raised qualified immunity in 47.5% of possible cases.

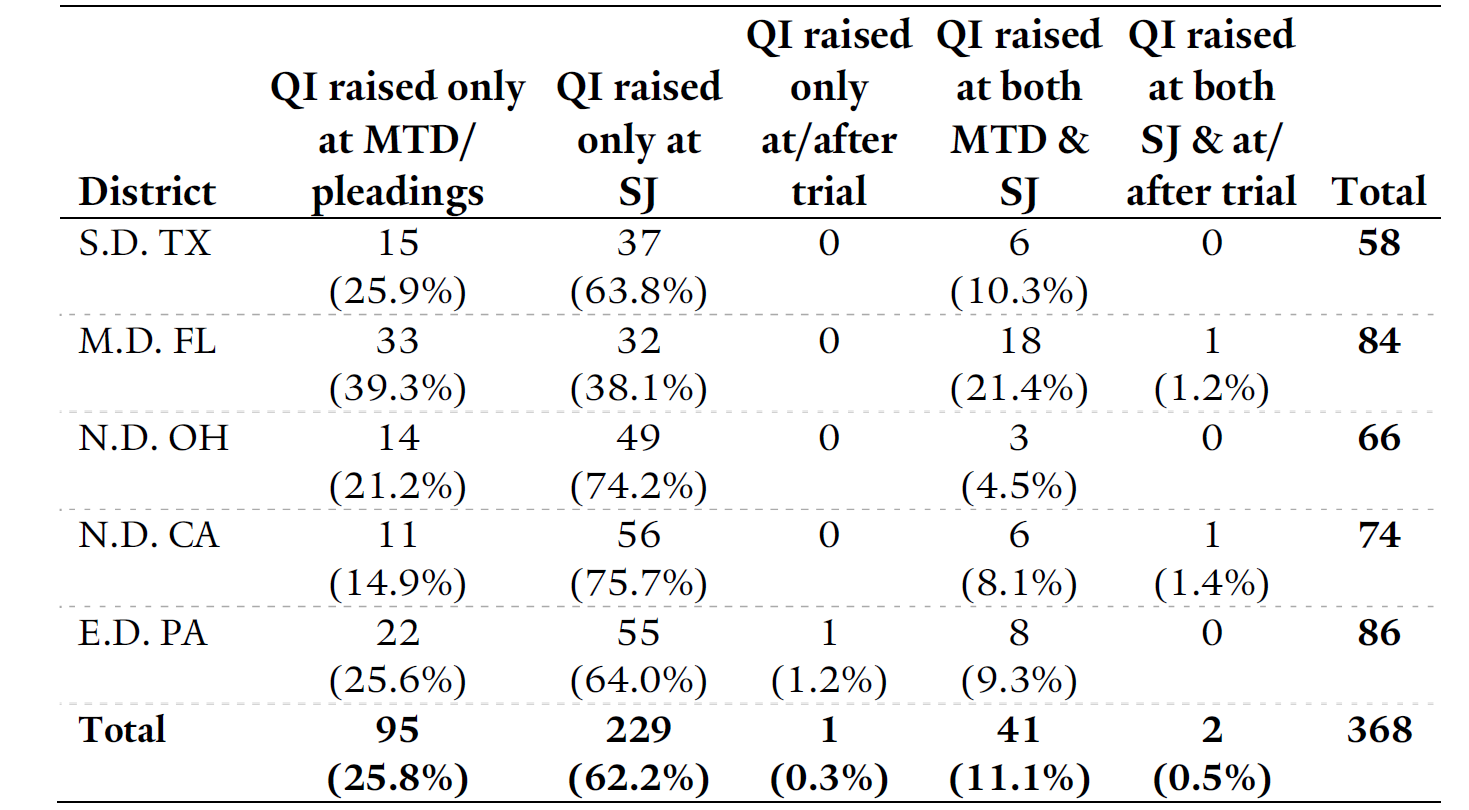

I also explored the stage(s) of litigation at which qualified immunity was raised. Of the 368 cases in which qualified immunity was raised at least once, defendants in ninety-five (25.8%) cases raised qualified immunity only in a motion to dismiss or motion for judgment on the pleadings, defendants in 229 (62.2%) cases raised qualified immunity only in a motion for summary judgment, and defendants in forty-one (11.1%) cases raised qualified immunity at both the motion to dismiss and summary judgment stages. Based on my review of motions and opinions available on Bloomberg Law, I can confirm only three cases in which defendants included qualified immunity in a motion at or after trial for judgment as a matter of law. My data almost certainly underrepresent the role qualified immunity plays at or after trial, however, as Bloomberg Law does not include oral motions or court decisions issued without a written opinion.85

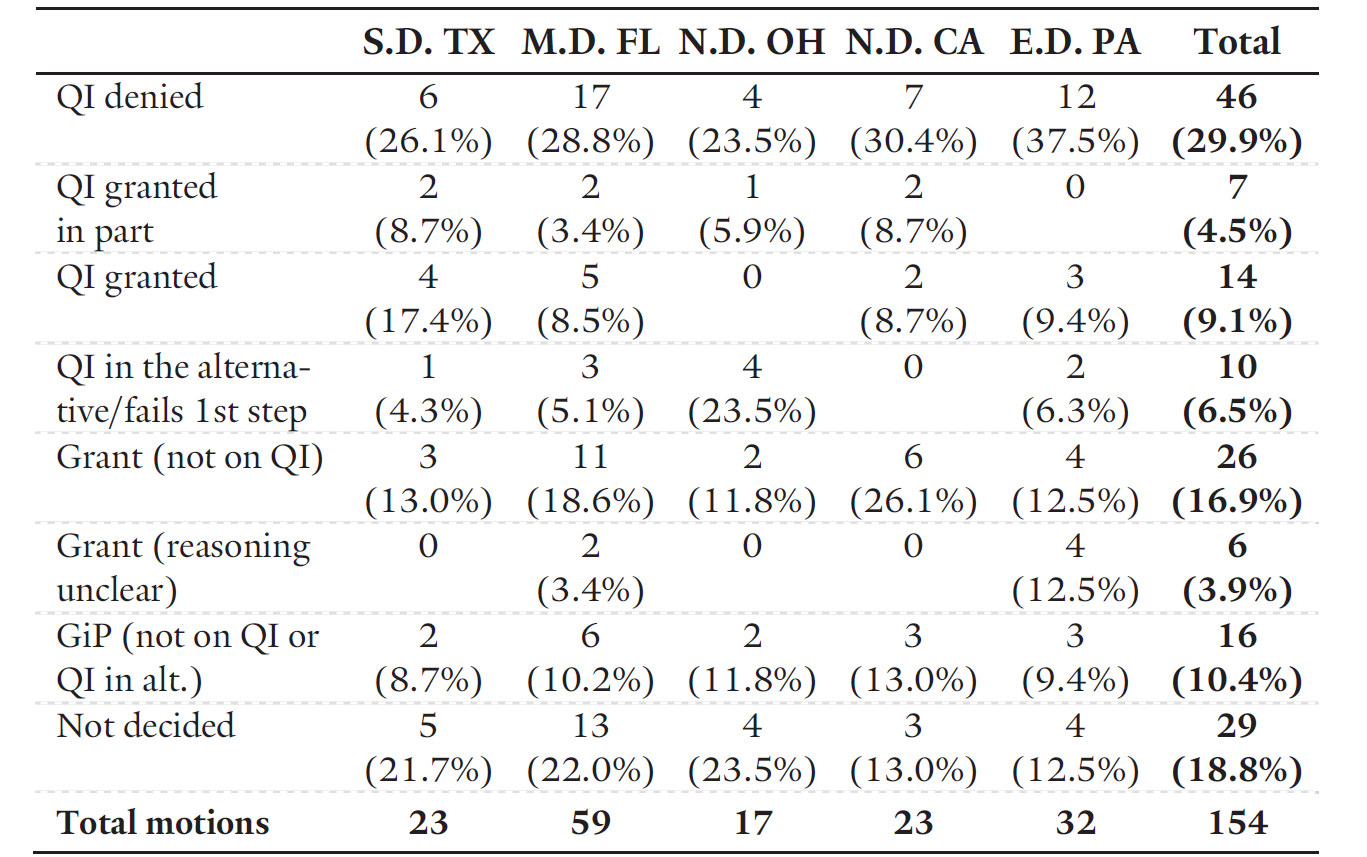

table 3.

timing of qualified immunity motions

Across the five districts in my study, defendants raised qualified immunity at summary judgment approximately twice as often as they did at the motion to dismiss stage. In cases where defendants brought one or more qualified immunity motions, defendants in 73.9% of the cases raised qualified immunity at summary judgment, whereas defendants in 37.0% of the cases raised qualified immunity in a motion to dismiss. There is, however, regional variation in this regard. Defendants in the Middle District of Florida were equally likely to raise qualified immunity at the pleadings stage and at summary judgment, whereas in the Northern District of Ohio and the Northern District of California defendants were more than three times more likely to raise qualified immunity at summary judgment than they were to raise the defense in a motion to dismiss.

Defendants in the Middle District of Florida were also more likely to raise qualified immunity at more than one stage of litigation—they raised qualified immunity at multiple stages of litigation in nineteen (22.6%) of the cases in which they raised the defense. Defendants in the other districts less frequently raised qualified immunity at multiple stages of litigation; they did so in six (10.3%) of the cases in which the defense was raised in the Southern District of Texas, in seven (9.5%) of the cases in which the defense was raised in the Northern District of California, in eight (9.3%) of the cases in which the defense was raised in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, and in three (4.5%) of the cases in which the defense was raised in the Northern District of Ohio.

I additionally sought to calculate how frequently defendants chose to raise qualified immunity motions in all the cases in which such motions could be brought. This calculation is relatively straightforward regarding motions to dismiss. Defendants could have brought motions to dismiss on qualified immunity grounds in any of the 979 cases in which the defense could be raised and did so in 136 (13.9%) of these cases.

Calculating the number of possible summary judgment motions on qualified immunity grounds is more complicated. Although defendants could bring a summary judgment motion in any case in which they could offer some evidence in support, defendants generally do not move for summary judgment without first engaging in at least some formal discovery.86 It is difficult to discern from case dockets to what extent parties have engaged in discovery, but the dockets do reflect whether a case management order has been issued, which generally sets the discovery schedule and is the first step of the discovery process. If entry of a case management order can serve as an indication that a case has entered discovery, and if one accepts that defendants in cases that have conducted some discovery could move for summary judgment, then there are 577 cases in my dataset in which defendants could have moved for summary judgment. Defendants brought summary judgment motions on qualified immunity grounds in 272 (47.1%) of these cases.

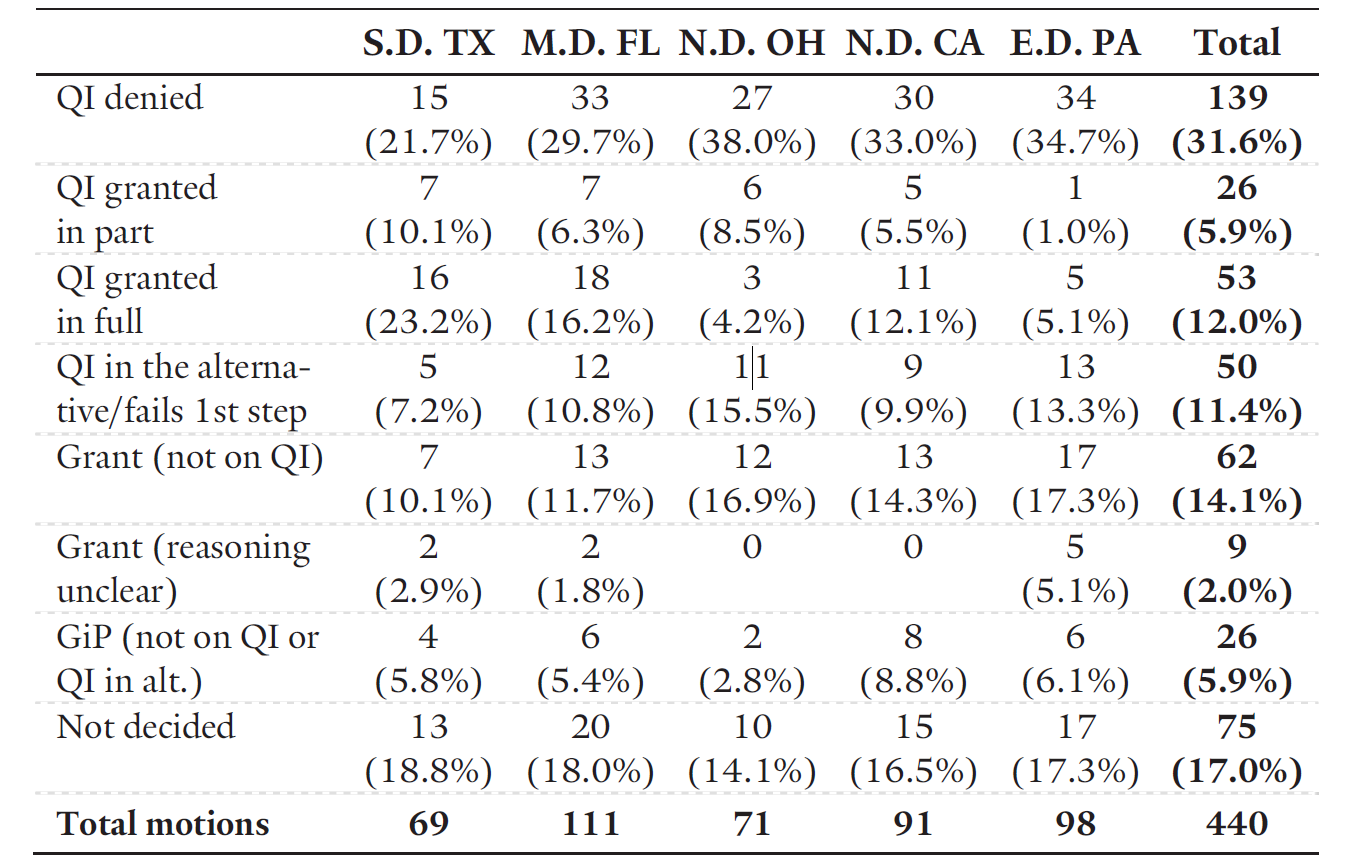

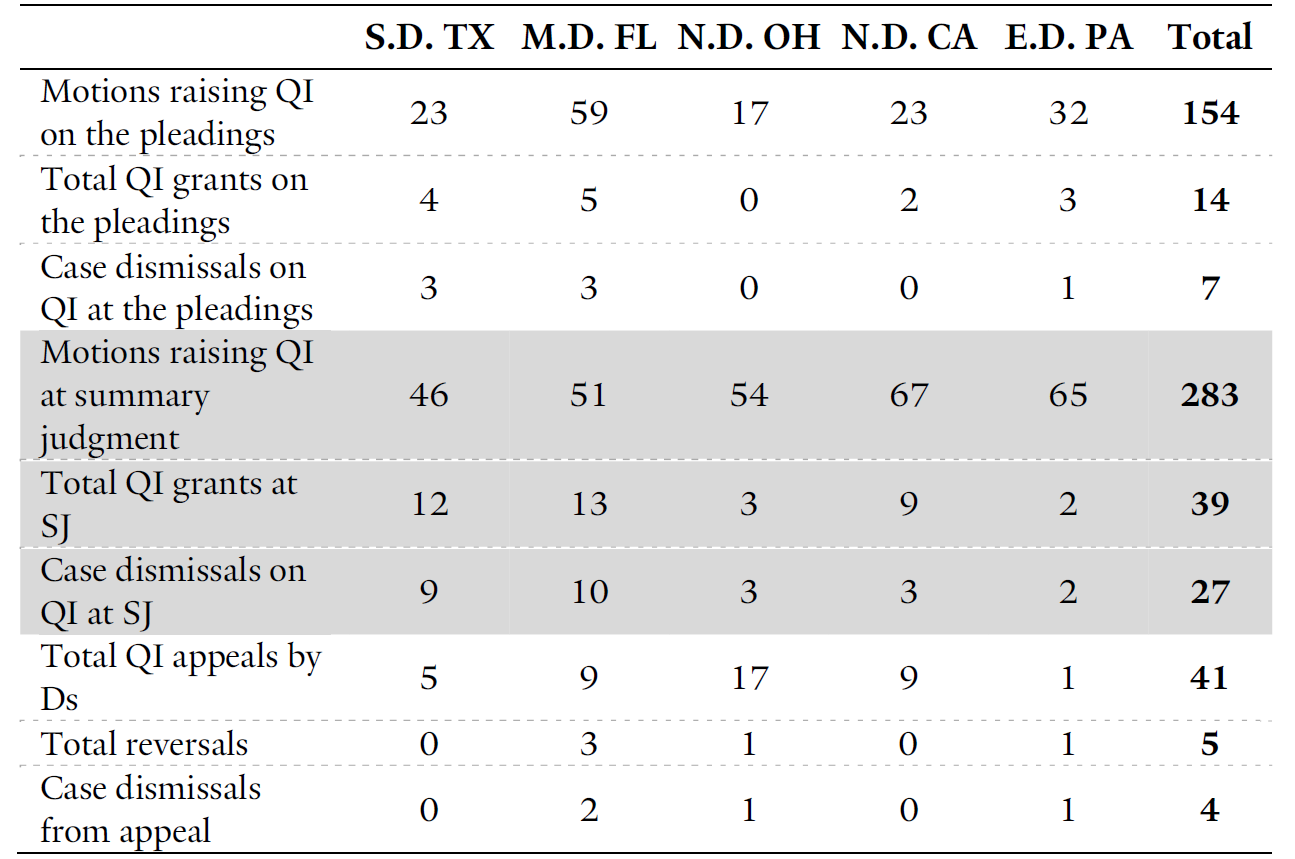

I also calculated the total number of qualified immunity motions brought by defendants. Defendants sometimes raised qualified immunity in multiple motions to dismiss or summary judgment motions that were resolved by the court in separate opinions: if, for example, defendants moved to dismiss on qualified immunity grounds, the court granted the motion with leave to amend, and the plaintiff filed an amended complaint, the defendants might again move to dismiss on qualified immunity grounds.87 Defendants filed a total of 440 qualified immunity motions in the 368 cases in which they raised the defense. Table 4 reflects the stage of litigation at which these 440 motions were brought and, again, reflects that defendants file significantly more qualified immunity motions at summary judgment than at the motion to dismiss stage. Of the 440 qualified immunity motions filed, 154 (35.0%) were filed in a motion to dismiss or motion for judgment on the pleadings, and 283 (64.3%) were filed at summary judgment.

table 4.

total qualified immunity motions filed, by stage of litigation

table 5.

number of qualified immunity motions per case

Table 5 reflects the distribution of these 440 motions among the 368 cases in which the defense was raised. Table 5 shows that when defendants raise qualified immunity they usually do so in only one motion, but that defendants in the Southern District of Texas and Middle District of Florida are more likely than defendants in the other three districts to file multiple motions raising qualified immunity.

Finally, I explored how frequently defendants raise other types of defenses in motions to dismiss or for judgment on the pleadings and in summary judgment motions. Qualified immunity is usually one of several arguments defendants make in their motions to dismiss and for summary judgment. Indeed, defendants sometimes move to dismiss or for summary judgment without raising qualified immunity at all.

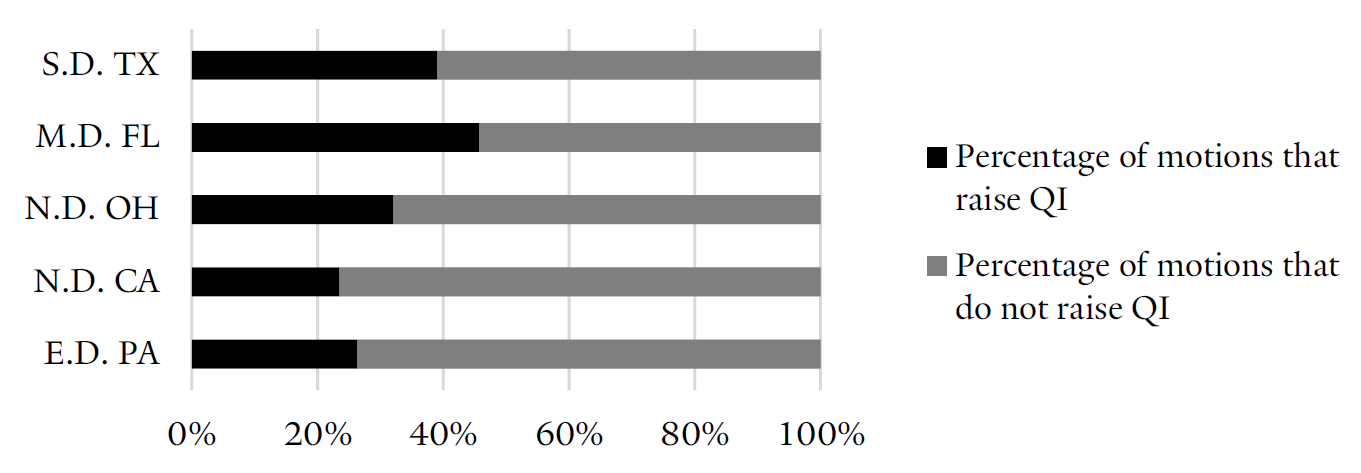

Of the 979 cases in my docket dataset in which defendants could raise qualified immunity, defendants filed a total of 462 motions to dismiss, and 154 (33.3%) included a qualified immunity argument.88 Defendants in the Middle District of Florida were the most likely to raise qualified immunity in motions to dismiss or for judgment on the pleadings—defendants included a qualified immunity argument in 45.4% of their motions, compared with 39.0% of the motions filed by defendants in the Southern District of Texas, 32.1% of the motions filed by defendants in the Northern District of Ohio, 26.2% of the motions filed by defendants in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, and 23.5% of the motions filed by defendants in the Northern District of California. Motions to dismiss or for judgment on the pleadings that did not raise qualified immunity argued instead that the complaint did not satisfy plausibility pleading requirements, concerned a claim that was barred by a criminal conviction, or otherwise did not state a legally cognizable claim.89

figure 1.

motions to dismiss/for judgment on the pleadings

figure 2.

summary judgment motions

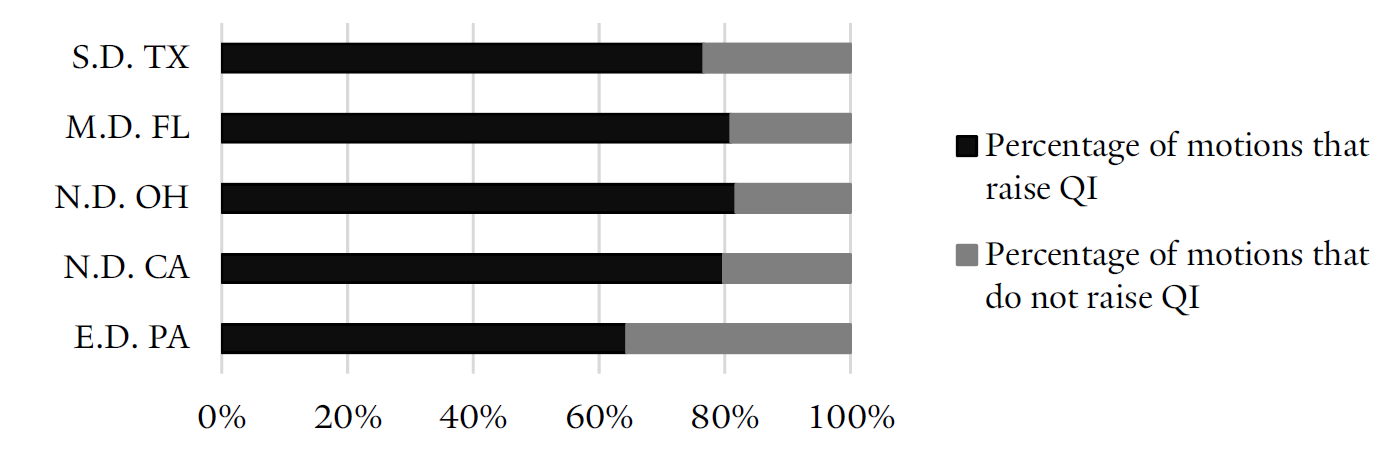

Defendants in all five districts were far more likely to include a qualified immunity argument in their summary judgment motions. Defendants filed 374 motions for summary judgment, and 283 (75.7%) of those motions included an argument based on qualified immunity. There was some variation among the districts in this area as well, although the regional variation was less pronounced here than in other aspects of qualified immunity litigation practice.90

C. District Courts’ Decisions: The Success Rate of Qualified Immunity Motions

This Section examines how frequently district courts grant motions to dismiss and for summary judgment on qualified immunity grounds. As I have shown, qualified immunity is almost always raised in conjunction with other arguments in motions to dismiss or for summary judgment. My focus here is on the way the district court evaluates the qualified immunity argument.

table 6.

success of motions raising qualified immunity

In the five districts in my docket dataset, defendants raised qualified immunity in a total of 440 motions. Table 6 reflects the way in which district courts resolved those motions.91Across the five districts in my study, qualified immunity motions were denied 31.6% of the time.92 Qualified immunity motions in these five districts were granted in part—on some claims or defendants but not others—5.9% of the time and granted in full on qualified immunity grounds 12.0% of the time. In another 11.4% of the decisions, courts concluded that the plaintiff had not met her burden of establishing a constitutional violation and either declined to reach the second step of the qualified immunity analysis (whether a reasonable officer would have believed that the law was clearly established) or granted qualified immunity in the alternative.93 Courts in 14.1% of the decisions granted defendants’ motions on other grounds without addressing qualified immunity, and in another 2.0% of the decisions the courts offered little or no rationale. Courts in 5.9% of the decisions granted the motion in part without mentioning qualified immunity, or on qualified immunity in the alternative. And district courts in my study did not decide 17.0% of the motions raising qualified immunity, usually because the cases settled or were voluntarily dismissed while the motions were pending.

There was substantial variation in courts’ decisions across the districts in my study. The Southern District of Texas had the lowest rate of qualified immunity denials (21.7%). In the remaining four districts, judges denied 30-38% of defendants’ qualified immunity motions. The Southern District of Texas also had the highest rate of qualified immunity grants: courts in the Southern District of Texas granted 33.3% of defendants’ qualified immunity motions in part or full on qualified immunity grounds. In contrast, courts in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania granted only 6.1% of the qualified immunity motions in whole or part on qualified immunity grounds.94

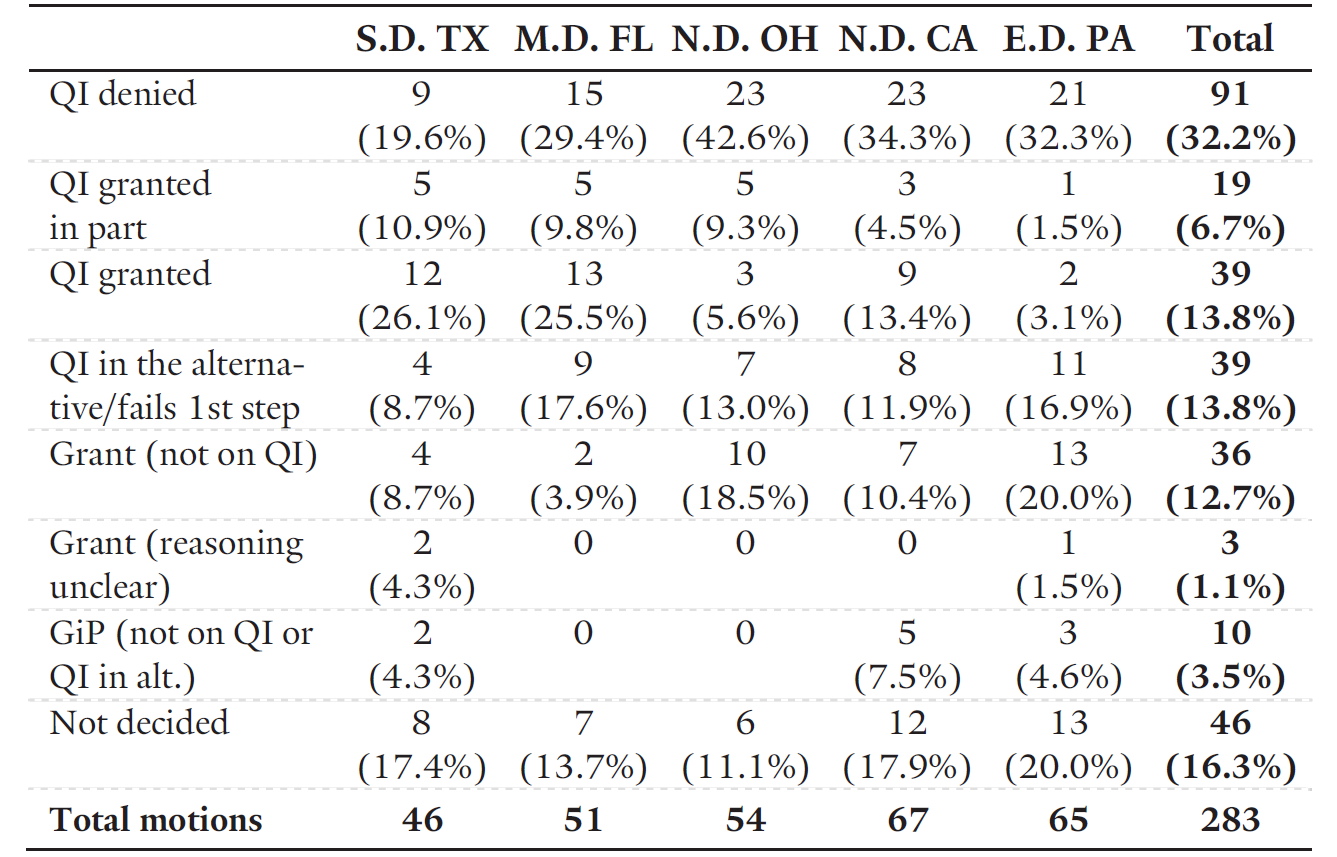

table 7.

rulings on motions to dismiss/on the pleadings that raised qualified immunity

table 8.

rulings on summary judgment motions that raised qualified immunity

I additionally evaluated differences in courts’ decisions at the motion to dismiss and summary judgment stages.95 Of the 154 motions to dismiss and motions for judgment on the pleadings raising qualified immunity, courts granted seventy-nine (51.3%) of the motions in whole or part. Twenty-one (26.6%) of those seventy-nine full or partial grants were decided on qualified immunity grounds. Of the 283 summary judgment motions raising qualified immunity, courts granted 146 (51.6%) in whole or part. Fifty-eight (39.7%) of those 146 full or partial grants were decided on qualified immunity grounds. In other words, although courts were equally likely to grant summary judgment motions and motions to dismiss, courts were more likely to grant summary judgment motions on qualified immunity grounds than they were to grant motions to dismiss on qualified immunity grounds. But courts more often than not granted both types of motions on grounds other than qualified immunity.

D. Circuit Courts’ Decisions: The Frequency and Success of Qualified Immunity Appeals

A complete examination of the role qualified immunity plays in constitutional litigation must examine the frequency and outcome of qualified immunity appeals. Defendants can appeal denials of qualified immunity immediately, and any qualified immunity decision can be appealed after a final judgment in the case.96

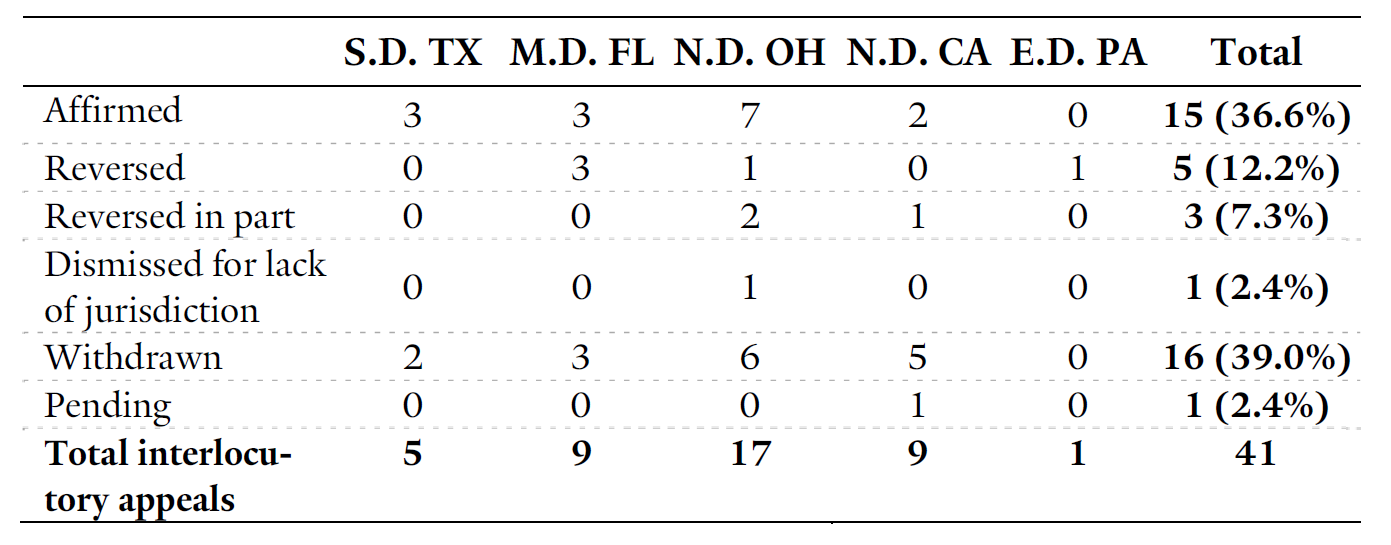

table 9.

interlocutory appeals of qualified immunity denials

Defendants immediately appealed 41 of the 189 qualified immunity decisions in my docket dataset that were denied or granted in part and thus could have been appealed at this stage of the litigation—an interlocutory appeal rate of 21.7%. Across the five districts in my dataset, more than one-third of the lower courts’ decisions were affirmed on interlocutory appeal, 12.2% were reversed in whole, 7.3% were reversed in part, and 39.0% were withdrawn by the parties without a decision by the court of appeals.

table 10.

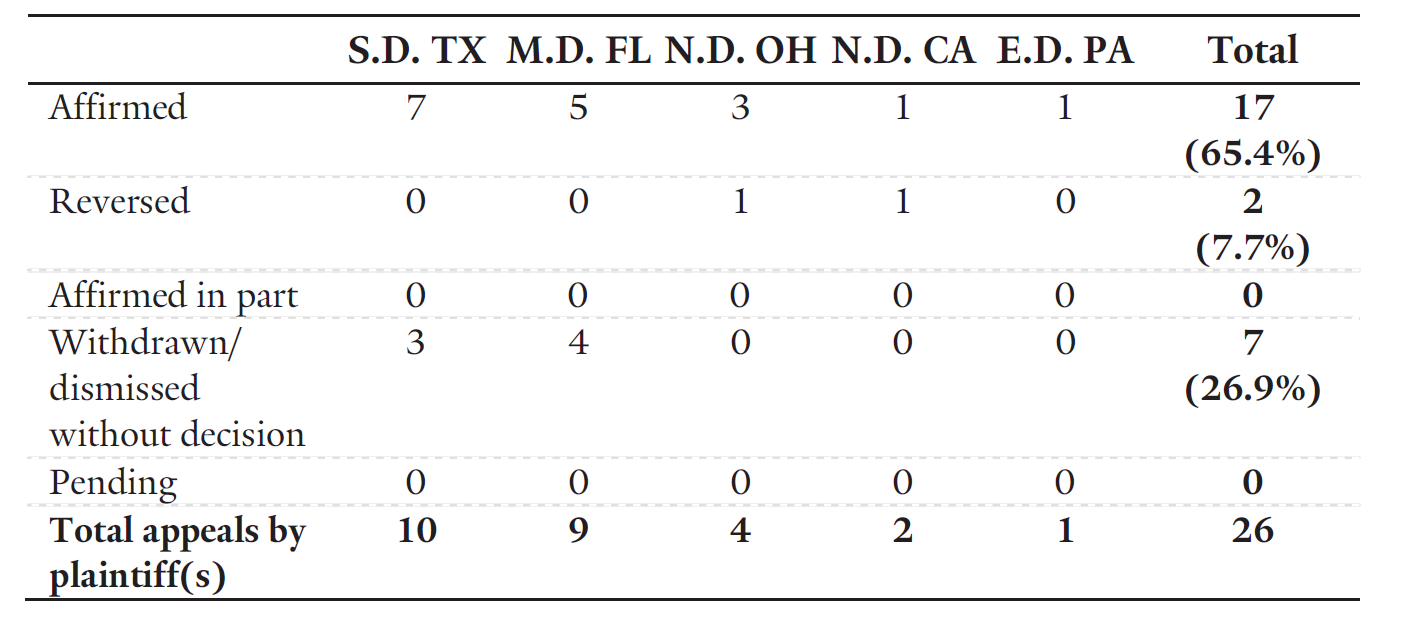

final appeals of qualified immunity grants

I also tracked the frequency with which plaintiffs appealed qualified immunity grants after a final judgment in the case.97 Plaintiffs appealed twenty-six (32.9%) of the seventy-nine decisions granting defendants’ motions on qualified immunity grounds in whole or part.98 Lower court decisions granting qualified immunity were affirmed 65.4% of the time and reversed 7.7% of the time. Almost 27% of the appeals were withdrawn without a decision.

E. The Impact of Qualified Immunity on Case Dispositions

A final question concerns the frequency with which a grant of qualified immunity results in the dismissal of Section 1983 cases. There are multiple ways to frame this inquiry. First, there is the question of which cases should be counted in the numerator—cases dismissed on qualified immunity grounds. I have included qualified immunity grants in this category unless the court ended its qualified immunity analysis after concluding that the plaintiff could not establish a constitutional violation, or granted the motion on qualified immunity in the alternative. Although the question of whether a constitutional violation occurred is the first step of the qualified immunity analysis, the court would also need to resolve this question in the absence of qualified immunity. And although a court’s decision to grant qualified immunity in the alternative may influence its dispositive holding in some manner, the qualified immunity decision was not necessary to resolve the case.99

In addition, I have counted a case as dismissed on qualified immunity grounds only if the entire case has been dismissed as a result of the motion. One might assume that a grant of qualified immunity will always end a case. Yet there are multiple scenarios in which a case can continue after a grant of qualified immunity. At the pleadings stage, a court may grant a motion to dismiss on qualified immunity but also grant the plaintiff an opportunity to amend her complaint.100 Not all defendants in a case will necessarily move to dismiss on qualified immunity grounds,101 or a defendant may seek qualified immunity regarding some but not all claims against him.102 State law claims may also remain for which qualified immunity is not available, and these claims may proceed in federal court or be remanded to and pursued in state court.103 In addition, municipalities cannot assert qualified immunity; accordingly, if there is a municipality named in the case at the time qualified immunity is granted, the case will continue.104 Under each of these circumstances, government officials still face the possibility that they will be required to participate in discovery and trial as defendants, representatives of the defendants’ agency, and/or witnesses to the events in question.105

table 11.

impact of qualified immunity, by stage of litigation

As Table 11 shows, there are fifty-three motions in my dataset that district courts granted in full on qualified immunity grounds—fourteen at the pleadings stage and thirty-nine at summary judgment. Of those fifty-three motions, thirty-four (64.2%) were dispositive, meaning that the cases were dismissed as a result of the qualified immunity decision. Half of qualified immunity grants at the pleadings stage led to case dismissals, and 69.2% of qualified immunity grants at summary judgment led to case dismissals. Defendants brought forty-one interlocutory appeals of qualified immunity denials, and courts of appeals reversed five (12.2%) of those decisions. All five reversals were of summary judgment decisions, and four of the five resulted in case dismissals. In total, qualified immunity led to dismissal of thirty-eight cases in my dataset.

The next question, when thinking about the impact of qualified immunity on case disposition, is how to frame the denominator—the universe of cases against which to measure the cases dismissed on qualified immunity grounds. It is my view that the broadest definition of the denominator—all 1,183 Section 1983 cases filed against law enforcement—offers the most accurate picture of the role qualified immunity plays in Section 1983 litigation. Yet, as I will show, there are at least three ways to frame the denominator, and each answers a different question about the extent to which qualified immunity achieves its intended goals.

One way to think about the impact of qualified immunity is to consider the frequency with which a defendant’s motion to dismiss or for judgment on the pleadings, for summary judgment, or for judgment as a matter of law on qualified immunity grounds actually leads to the dismissal of a case—whether because the motion is granted or because the motion is denied by the district court but reversed on appeal. Presumably, a defendant will only bring a qualified immunity motion when two conditions are met: he has a non-frivolous basis for the motion, and he believes that the costs of bringing the motion are justified by the likelihood of success or some other benefit associated with the motion. Accordingly, this framework assesses the frequency with which qualified immunity results in the dismissal of cases in which both these things are true.

Defendants brought 440 qualified immunity motions in a total of 368 cases in the five districts in my study: defendants raised qualified immunity in 154 motions to dismiss and raised qualified immunity in 283 summary judgment motions. Courts granted 9.1% of the motions to dismiss on qualified immunity grounds, and 4.5% of the motions resulted in case dismissals. Courts granted 13.8% of the summary judgment motions on qualified immunity grounds, and 9.5% of the motions resulted in case dismissals. Defendants brought forty-one interlocutory appeals of qualified immunity denials, courts of appeals reversed five (12.2%) of those decisions, and four of the five were dismissed as a result. In total, thirty-eight (8.6%) of the 440 qualified immunity motions raised by defendants in my dataset resulted in case dismissals, and 10.3% of the 368 cases in which qualified immunity was raised were dismissed on qualified immunity grounds.

Another way to assess the impact of qualified immunity on case outcomes is to examine what percentage of the 979 cases in my dataset in which qualified immunity could be raised were in fact dismissed on qualified immunity grounds. One objection to this framing might be that it includes cases that defendants declined to challenge on qualified immunity grounds. But qualified immunity motions would not necessarily have failed in these cases; rather, defendants in these cases concluded that the costs of raising the defense were not justified by the likelihood of success or other benefits of bringing the motions. Moreover, this broader framework illustrates the frequency with which qualified immunity doctrine serves its intended and expected role of shielding government officials from burdens associated with discovery and trial. Evaluated in this manner, qualified immunity is less frequently successful. Qualified immunity was the basis for dismissal in 3.9% of the 979 cases in which the defense could be raised: just seven (0.7%) of cases were dismissed on qualified immunity grounds at the motion to dismiss stage, and thirty-one (3.2%) of cases were dismissed on qualified immunity grounds at summary judgment—either by the district court or on appeal.

Indeed, to evaluate fully the role that qualified immunity plays in the resolution of constitutional claims against law enforcement, the most appropriate denominator is the complete universe of 1,183 cases in my dataset. This approach includes cases that could not be resolved on qualified immunity grounds—because the cases were either brought only against municipalities or sought only equitable relief. But to the extent that the Court views qualified immunity doctrine as a shield for all government officials—not only defendants—from burdens associated with discovery and trial, a thorough assessment of qualified immunity’s role should take account of all the cases in which government officials must participate. Qualified immunity was the basis for dismissal in 3.2% of the 1,183 cases in my dataset: 0.6% of cases were dismissed on qualified immunity grounds at the motion to dismiss stage, and 2.6% of cases were dismissed on qualified immunity grounds at summary judgment—either by the district court or on appeal.106

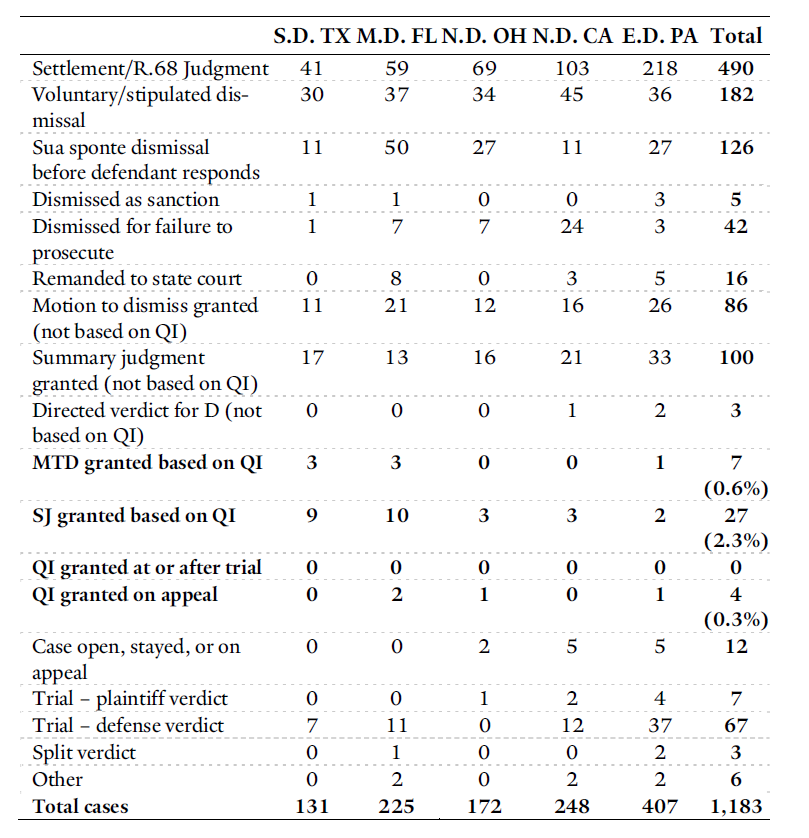

My data show that qualified immunity is rarely the formal reason that Section 1983 cases are dismissed. How, then, are Section 1983 suits against law enforcement resolved? Table 12 reports case outcomes for the 1,183 cases in the five districts in my study.

table 12.

case dispositions

If one adopts the standard definition of plaintiff “success” to include jury verdicts, settlements, and voluntary or stipulated dismissals, the plaintiffs in my dataset succeeded in 682 (57.7%) cases.107 This success rate is similar to the results of Theodore Eisenberg and Stewart Schwab’s studies of non-prisoner Section 1983 cases.108 The remaining 42.3% of cases resolved in various ways: 256 (21.6%) were dismissed on motions to dismiss or for judgment on the pleadings, at summary judgment, or at or after trial on grounds other than qualified immunity; 173 (14.6%) were dismissed sua sponte before defendants answered, dismissed as a sanction, or dismissed for failure to prosecute; and thirty-seven (3.1%) were dismissed for other reasons or remain open. Thirty-eight (3.2%) were dismissed on qualified immunity grounds.

My data do not capture how frequently qualified immunity influences plaintiffs’ decisions to settle, or how frequently cases are decided on qualified immunity grounds even though other defenses are available. Instead, my data reflect the frequency with which a grant of qualified immunity formally ends a case. There is, once again, marked regional variation in the frequency with which qualified immunity leads to the dismissal of Section 1983 actions.109 But despite this regional variation, grants of qualified immunity motions infrequently end Section 1983 suits before discovery, and are infrequently the reason suits are dismissed before trial.

IV. implications

My findings undermine prevailing assumptions about the role qualified immunity plays in the litigation of Section 1983 claims. Accordingly, in this Part I consider the implications of my findings for ongoing discussions about the proper scope of qualified immunity in relation to its underlying purposes. First, I revisit empirical claims implicit in the Supreme Court’s qualified immunity decisions in light of my findings. Next, I consider why qualified immunity disposes of so few cases before trial. Armed with this more realistic appraisal of qualified immunity’s role, I argue that the Court has struck the wrong balance between fairness and accountability for law enforcement officers. Finally, I suggest that qualified immunity doctrine should be adjusted to comport with available evidence about the role the doctrine plays in constitutional litigation.

A. Toward a More Accurate Description of Qualified Immunity’s Role in Constitutional Litigation

The Court’s qualified immunity decisions paint a clear picture of the ways in which the Court believes the doctrine should operate: it should be raised and decided at the earliest possible stage of the litigation (at the motion to dismiss stage if possible), it should be strong (protecting all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law), and it should, therefore, protect defendants from the time and distractions associated with discovery and trial in insubstantial cases. Commentators similarly believe that qualified immunity is often raised by defendants, usually granted by courts, and causes many cases to be dismissed.110

My study shows that, at least in filed cases, qualified immunity rarely functions as expected. Defendants could not or did not need to raise qualified immunity in 17.3% of the 1,183 cases in my docket dataset, either because the cases did not name individual defendants or seek monetary damages, or because the cases were dismissed sua sponte by the court before the defendants had an opportunity to answer. Defendants raised qualified immunity in motions to dismiss and motions for judgment on the pleadings in only 13.9% of the cases in which the defense could be raised.111 Courts granted those motions on qualified immunity grounds 9.1% of the time, but those grants were not always dispositive because additional claims or defendants remained, or because plaintiffs were given the opportunity to amend. As a result, just seven of the 1,183 cases in my docket dataset were dismissed at the motion to dismiss stage on qualified immunity grounds.

Qualified immunity more often prevented cases from proceeding past summary judgment. Defendants were more likely to include qualified immunity in motions for summary judgment than in motions to dismiss, and courts were more likely to grant summary judgment motions than motions to dismiss on qualified immunity grounds.112 Moreover, courts of appeals reversed five denials of summary judgment motions on interlocutory appeal and granted qualified immunity in these cases. Yet qualified immunity motions at the summary judgment stage rarely shield government officials from discovery because most summary judgment motions require at least some depositions or document exchange.113 And grants of qualified immunity at summary judgment relatively rarely achieved their goal of protecting government officials from trial—such decisions by the district courts or courts of appeals disposed of plaintiffs’ cases just thirty-one times across the five districts in my study, amounting to just 2.6% of the 1,183 cases in my dataset.

Qualified immunity is likely raised more often at or after trial than my data suggest. But even if many more qualified immunity motions are made during or after trial, and even if qualified immunity regularly convinces judges and juries to enter defense verdicts, qualified immunity would still fail to serve its expected role. Qualified immunity doctrine is intended to shield government officials from burdens associated with litigation and trial. A grant of qualified immunity entered during or after trial has come too late to shield government officials from these assumed burdens.

My data demonstrate considerable regional differences in the litigation and adjudication of qualified immunity across the country. Scholars have observed that the federal circuits interpret qualified immunity standards differently.114 My findings suggest that regional differences in qualified immunity doctrine affect the decisions of courts and litigants. Defendants in the Southern District of Texas and the Middle District of Florida were more likely to raise qualified immunity than defendants in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania and the Northern District of California; courts in the Southern District of Texas and the Middle District of Florida were more likely to grant defendants’ qualified immunity motions than were judges in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania and the Northern District of California; and grants of qualified immunity ended more cases in the Southern District of Texas and the Middle District of Florida than in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania and the Northern District of California. But even in the Southern District of Texas—the district in my dataset most likely to dismiss cases on qualified immunity grounds—just 2.3% of all suits were dismissed on qualified immunity grounds at the motion to dismiss stage, and 6.9% of all suits were dismissed at summary judgment on qualified immunity grounds.115 Unless the vast majority of law enforcement officer defendants in the Southern District of Texas are “plainly incompetent” or have “knowingly violate[d] the law,”116 qualified immunity is not playing its expected role even in the district in my dataset most sympathetic to the defense.

Although qualified immunity is rarely the reason that Section 1983 cases end, there are other ways in which qualified immunity doctrine might influence the litigation of constitutional claims against law enforcement. For example, qualified immunity may discourage people from ever filing suit. Available evidence suggests that just 1% of people who believe they have been harmed by the police file lawsuits against law enforcement.117 We do not know how frequently qualified immunity doctrine plays a role in the decision not to sue. But available evidence suggests that qualified immunity often factors into plaintiffs’ attorneys’ decisions about whether to accept potential clients. When Alexander Reinert interviewed plaintiffs’ attorneys about qualified immunity in Bivens cases, attorneys reported that “the qualified immunity defense play[s] a substantial role at the screening stage.”118 Attorneys described being discouraged from accepting civil rights cases both because qualified immunity motions can be difficult to defeat and because the costs and delays associated with litigating qualified immunity can make the cases too burdensome to pursue.119 But attorneys also described qualified immunity as one of many factors they considered when deciding whether to accept a case, and we do not know how attorneys weigh these different considerations.120

Even when cases are filed, qualified immunity may influence litigation decisions in ways that are not easily observable through docket review. For example, it may be that a pending qualified immunity motion will cause a plaintiff to settle her claims. Consistent with this theory, seventy-five (17.0%) of the qualified immunity motions in my dataset were never decided, presumably because the parties settled while the motions were pending.121 Of the sixty-seven qualified immunity interlocutory and final appeals in my dataset, twenty-three (34.3%) were withdrawn or dismissed without decision, which suggests that many of those cases settled while on appeal.122 When the Supreme Court has described the ways in which it expects qualified immunity to shield government officials from discovery and trial, it has never suggested that the doctrine might serve this function by discouraging people from filing lawsuits or pursuing their claims. But these are certainly ways in which qualified immunity could achieve this goal.

A complete understanding of the frequency with which qualified immunity protects government officials from discovery and trial would measure these other potential litigation effects. For the time being, available evidence suggests that qualified immunity may make it more difficult for plaintiffs to secure representation and may encourage plaintiffs to settle, but it is infrequently the formal reason that cases end.

B. Why Qualified Immunity Disposes of So Few Cases