The Private Search Doctrine After Jones

Introduction

In United States v. Jacobsen,1 the Supreme Court created a curious aspect of Fourth Amendment law now known as the private search doctrine.2 Under the private search doctrine, once a private party has conducted an initial search independent of the government, the government may repeat that search, even if doing so would otherwise violate the Fourth Amendment. The private party’s search renders the subsequent government “search” not a search in the constitutional sense.

Jacobsen is based on the privacy theory of the Fourth Amendment introduced by the Court in Katz v. United States.3 According to the Court in Jacobsen, a private search—even if unauthorized—destroys an individual’s reasonable expectation of privacy. Thus, by merely repeating the search, the government does not further infringe on a person’s privacy.4 The private search doctrine is invoked by courts to justify police actions with somewhat surprising frequency.5

In 2012—twenty-eight years after Jacobsen—the Supreme Court restructured Fourth Amendment doctrine in United States v. Jones.6 In Jones, the Court held that the reasonable expectation of privacy test is not the only definition of a Fourth Amendment search. A search also occurs if the police trespass on a constitutionally protected area in order to obtain information, even if the trespass does not violate the property owner’s reasonable expectation of privacy. The full implications of Jones are still being explored. In this Essay, I argue that Jacobsen is irrelevant to the trespass definition of a search under Jones. A prior private search may destroy a person’s expectation of privacy, but it does not change whether the police trespassed on a constitutionally protected area in order to obtain information. Therefore, a government trespass that qualifies as a search under Jones is still a search even if its scope is limited to the scope of a prior private search.7 Jacobsen comes into play only if it is necessary to appeal to Katz to characterize the government action as a search.

I. defining “search”

The nature of the pre-Katz Fourth Amendment doctrine is disputed. Justice Scalia’s opinion for the Court in Jones characterizes the pre-Katz doctrine as an “exclusively property-based approach”8 to the law of searches, and claims that “for most of our history the Fourth Amendment was understood to embody a particular concern for government trespass upon the areas (‘persons, houses, papers, and effects’) it enumerates.”9 Many scholars concur in this analysis.10 Professor Orin S. Kerr, on the other hand, argues that this “common wisdom is false,”11 and that while “physical penetration”12 was the paradigm for identifying searches, “the Court [had] distinguished physical penetration from the technical doctrine of trespass.”13

Whichever view is accurate, there is general consensus that Katz at least formally redefined “search.”14 Katz held that placing an electronic listening device on the outside of a public phone booth was a search under the Fourth Amendment, despite a lack of physical intrusion or trespass.15 The Court held that a search occurs when “[t]he Government’s activities... violate[] the privacy upon which [a person] justifiably relie[s].”16 Justice Harlan’s concurrence, which has become the canonical statement of the test, described it as whether the government has invaded “a constitutionally protected reasonable expectation of privacy.”17

In Jones, the Supreme Court once again changed direction and revived the “common-law trespassory test” as an alternative to Katz’s reasonable expectation of privacy definition of search.18 While the Court disclaimed the novelty of its approach by alleging that “Katz did not narrow the Fourth Amendment’s scope”19—that is, that the pre-Katz trespass theory of the Fourth Amendment had always survived and that Katz had only added to it—Jones “came as a surprise to every student and scholar of the Fourth Amendment.”20

The trespass test revived by Jones has three elements: (1)a trespass21 (2)on a constitutionally protected area22 (3)”conjoined with... an attempt to find something or to obtain information.”23 Kerr and others have grappled with defining “trespass” as it is used in the Jones test.24 This Essay does not attempt to sketch the precise contours of Jones, but rather addresses the interaction between Jones and Jacobsen.

ii. the private search doctrine

Building on a prior splintered decision,25 Jacobsen created the private search doctrine. In Jacobsen, FedEx employees, pursuant to a company insurance policy, opened a package that had been damaged in transit.26 Inside, they found a suspicious white powdery substance.27 The employees repackaged the shipment’s contents and then notified the DEA.28 When DEA agents arrived, they removed the powder from the package and conducted a field test, which indicated the substance was cocaine.29

The Supreme Court held that the question of whether the DEA’s actions were a “search” in the constitutional sense “must be tested by the degree to which they exceeded the scope of the private search,” because that would determine how much “additional invasion[] of [the] respondent’s privacy” had occurred.30 The Court saw no difference between the government using information it obtained from a third party and the government searching a container that a third party had already searched.31 The Court’s reasoning turned entirely on an analysis of the package owner’s reasonable expectation of privacy.32 According to the Court, a government search that merely repeats a prior private search does not invade an individual’s reasonable expectation of privacy because that expectation of privacy has already been destroyed.

iii. jacobsen after jones

Jones restored the logic and language of trespass that had been missing from Fourth Amendment doctrine since Katz.33 The implications of that paradigm shift for Jacobsen’s private search doctrine, which have not yet been explored in detail,34 are significant. Jacobsen addresses whether government actions violate a reasonable expectation of privacy. Jones, however, makes that determination only half of the threshold Fourth Amendment inquiry—courts must still evaluate whether the action in question constitutes a trespass. Therefore, even if a particular action passes Jacobsen’s test (and is thus not a search under Katz), it may still be a search under Jones. Lower courts need not wait for the Supreme Court to acknowledge this explicitly. Instead, they should simply recognize that Jacobsen’s holding is limited to the Katz half of the definition of “search.”

A. Jacobsen Does Not Apply to Jones Searches

The reasoning of Jacobsen turns entirely on the reasonable expectation of privacy test, which, when the case was decided, was the sole test to determine whether a government action was a search. The Court concluded that once a private search was conducted, the government did not further invade a person’s privacy as long as it kept its own search within the bounds of the private search. This strict focus on the searched party’s expectation of privacy is evident in a footnote in which the Court insists on a distinction between “container[s] which can support a reasonable expectation of privacy” and those that cannot—that is, those that have already been searched by a private party.35 From a privacy perspective, the Court’s reasoning is defensible, whether one ultimately agrees with it or not.36 On a secrecy-focused conception of privacy, once information has been revealed to another person, the expectation of privacy is fully frustrated.37

Trespass works differently. It protects an individual’s interest in excluding others from entering or interfering with his or her property. The fact that someone has previously entered or interfered does almost nothing to erode the interest in exclusion. While the doctrine of adverse possession recognizes that property interests can be eroded by infringement, such erosion requires continuous violations over a long period of time, rather than the single violation that destroys privacy. The interests protected by Jones are therefore more robust—at least, in their susceptibility to erosion by violation—than the interests protected by Katz. This difference is fatal to an extension of Jacobsen to Jones searches. Jacobson focused on the ease with which an individual’s privacy interest may be eroded; the property interest central to Jones, however, is not so easily destroyed. Thus, a prior private search does not have the same relevance to a trespass inquiry as it does to a privacy inquiry.

Trespass on a constitutionally protected area is not the entirety of the Jones test. The trespass must also be aimed at gathering information. The government might argue that the logic of Jacobsen, while inapplicable to the trespass inquiry, is relevant to the information-gathering requirement. If the government already knows what is inside a package, then, the argument goes, it is not seeking further information when it repeats the private search. But the government is, in fact, seeking information when it repeats the search: it wants confirmation that the private party’s information is true and accurate, and it wants the additional details that it may gain from personal observation (rather than from a second-hand report). If repeating the search really provided no additional information, there would be no reason to conduct the additional search.38 In this vein, the Court in Jones rejected “the argument that what would otherwise be an unconstitutional search is not such where it produces only public information.”39

B. Florida v. Jardines Confirms That Jacobsen Should Be Limited to Katz Searches

In two cases decided under Katz, United States v. Place40 and Illinois v. Caballes,41 the Court held that exposing a container or a car to a trained narcotics dog (that is, to a “dog sniff”) was not a search. After Jones, the Court held in Florida v. Jardines42 that Place and Caballes do not apply when the dog is walked up to the front door of a home, because doing so is a trespass on the curtilage of the home—“a constitutionally protected area.”43 Jardines thus did for the dog sniff rule what I argue should be done for the private search doctrine: limited its applicability to Katz searches, not Jones searches.

The Court justified its holdings in Place and Caballes by pointing out that “the information obtained [wa]s limited,” because “the sniff disclose[d] only the presence or absence of narcotics, a contraband item.”44 Because possession of contraband is not legitimate, “governmental conduct that only reveals the possession of contraband ‘compromises no legitimate privacy interest.’”45

The government argued that Place and Caballes should control Jardines, but the Court disagreed. The Court noted that it “need not decide whether the officers’ investigation of Jardines’ home violated his expectation of privacy under Katz.”46 Instead, “[t]hat the officers learned what they learned only by physically intruding on Jardines’ property to gather evidence is enough to establish that a search occurred.”47 Therefore, even though letting a narcotics dog sniff a front door could reveal only the presence or absence of narcotics in a home—and thus would not seem to invade Katz’s articulation of individuals’ reasonable expectation of privacy as discussed in Place and Caballes—bringing the dog up to the door is nonetheless a search, because it is a trespass.

Place and Caballes are typically grouped with the second part of Jacobsen, which held that a chemical field test of narcotics is not a search because it “can reveal [only] whether a substance is [narcotics].”48 However, these cases are also closely related to the private search doctrine developed in the first part of Jacobsen. The private search doctrine depends upon the fact that the prior private search provides the police with “a virtual certainty” that a subsequent search will not reveal “anything more than [they] already ha[ve] been told.”49

The dog sniff rule and the private search doctrine thus both turn on an evaluation of the nature and amount of information exposed by the government action—a crucial aspect of evaluating whether a reasonable expectation of privacy has been invaded. However, Jardines confirms the logic of Jones: these considerations are irrelevant when the governmental action in question is a trespass on a constitutionally protected area in pursuit of information. Doctrines that limit the definition of a search under the reasonable expectation of privacy theory do not necessarily apply in the context of trespass.

C. Jones Limits the Implications of—Rather than Overruling—Jacobsen

In one case in which a district court apparently recognized that Jacobsen does not apply to searches under Jones,50 the government argued on appeal that lower courts must wait for the Supreme Court to explicitly hold Jacobsen inapplicable to Jones searches.51 However, the rule requiring lower courts to wait for the Supreme Court to explicitly overturn its own precedents52 was developed for situations in which the Court’s prior reasoning is undermined by cases that are related but analytically distinct. It is a rule against lower courts anticipating the overruling of one Supreme Court case based on rationales indicated in another case. It does not apply where the intervening case directly applies to the facts of the previous case.

Under Katz, determining whether a government action was a “search” involved answering one question: did the action invade an individual’s reasonable expectation of privacy? Jacobsen answered the Katz question in a particular circumstance: repeating a prior private search does not further infringe on the privacy interest, and is therefore not a search under the Fourth Amendment. In deciding Jones, the Court added a second, independent test to the original Katz inquiry: was the government action a trespass on a constitutionally protected area for the purpose of gathering information? Therefore, after Jones, a person’s “Fourth Amendment rights do not rise or fall with the Katz formulation.”53

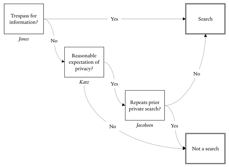

While Jones limits the applicability of the private search doctrine, it does not overrule Jacobsen. Jacobsen held that certain government actions do not qualify as invasions of an individual’s reasonable expectation of privacy. After Jones, however, certain government trespasses are searches, even if they do not invade reasonable expectations of privacy. Thus, while Jacobsen is still good law, it answers only the Katz half of the search inquiry. Cases that would have not been searches under Katz and Jacobsen may be searches under Jones. The relationship between the three cases is represented in the following diagram:

figure 1.

The Relationship Between Jones, Katz, and Jacobsen

|

Lower courts give full effect to Jacobsen when they apply it to Katz searches. Linking Jacobsen to Jones searches would be an extension, not an application of the private search doctrine. That Jones dictates a different result in some cases decided under Jacobsen—including, it seems, Jacobsen itself—does not mean that Jones overrules Jacobsen. While Jones’s creation of a second, independent test for what constitutes a search can change the result in cases decided when Katz was the only applicable test, Jones does so without thereby undermining the legal rules those cases created to apply the Katz test.

In Jones, the Supreme Court recognized a new way of violating the Fourth Amendment that it did not recognize when earlier cases, including Jacobsen, were decided. To the extent Jones overrules those earlier cases—by dictating a different result under the trespass test—Jones itself satisfies the requirement that the Supreme Court be the one to declare new rules that differ from its previous precedents, because Jones directly applies to Fourth Amendment search claims. The question of whether to extend doctrines developed under Katz (such as Jacobsen’s private search doctrine) to the Jones test is a question that lower courts can rightfully address in the first instance.

D. Applying Jacobsen After Jones

Jacobsen’s continuing role after Jones can be illustrated by considering two fact patterns based on Jacobsen itself. In the first, what would otherwise invade a reasonable expectation of privacy does not do so (and thus is not a search), because it merely repeats a prior private search. In the second, however, a physical trespass in pursuit of information remains a search despite the fact that it also repeats a prior private search.

First, suppose that FedEx employees, in a routine security check, x-ray a package and see something inside resembling illegal narcotics. They set the package aside and notify local law enforcement. An hour later, the police arrive. Before they get a warrant, the police want to see the x-ray image themselves. So, they have the FedEx employees run the package through the x-ray again. Based on their observations, the police obtain a warrant, open the package, and recover the narcotics. Normally x-raying a package would invade its owner’s reasonable expectation of privacy in the contents of the package, and would thus be a search under Katz.54 However, because the FedEx employees had already x-rayed the package and the police did precisely the same thing, Jacobsen suggests that the police x-ray is not a Katz search. Because an x-ray is likely not a physical trespass,55 Jones does not apply, making Katz and Jacobsen the entirety of the Fourth Amendment analysis on these facts.

Now, suppose that instead of x-raying a package, FedEx employees open it, check its contents, and find narcotics inside. They then put the narcotics back in the package and call the police. The police arrive, open up the package, and find the narcotics. Opening the package is likely a trespass (on an “effect[]”56), and was conducted in pursuit of information (confirmation of the contents). It is therefore a search under Jones. While the police were merely repeating the prior private search, the analysis never reaches Jacobsen because opening the package is a search regardless of whether it invades a reasonable expectation of privacy.

Conclusion

Jones created a new test for what counts as a search under the Fourth Amendment. This new test stands side-by-side with the reasonable expectation of privacy test under Katz. Jones’s analytical framework should be taken seriously in assessing other areas of Fourth Amendment doctrine. Some rationales that resonate in the context of privacy may not carry equal import in the context of trespass. The justification for the private search doctrine is one such example. While Jacobsen can still be appropriately applied to Katz searches, lower courts should not extend it to Jones searches.

Andrew MacKie-Mason is a J.D. Candidate, The University of Chicago Law School, 2017. The author wishes to thank Lisa Bixby for her insightful comments, and the editors of the Yale Law Journal Forum for their hard work on this piece.

Preferred Citation: Andrew MacKie-Mason, The Private Search Doctrine After Jones, 126 Yale L.J. F. 326 (2017), http://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum /the-private-search-doctrine-after-jones.

See United States v. Lichtenberger, 786 F.3d 478, 481 (6th Cir. 2015) (“The private search doctrine originated from the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Jacobsen.”). The private search doctrine is distinct from the state action requirement, which holds that purely private actions do not implicate the Fourth Amendment, though the state action requirement was also discussed in Jacobsen. See Jacobsen, 466 U.S. at 115.

See, e.g., United States v. Sparks, 806 F.3d 1323, 1334-36 (11th Cir. 2015); United States v. Odoni, 782 F.3d 1226, 1238-40 (11th Cir. 2015) (extending the private search doctrine to a situation in which the initial search was conducted by foreign governmental officials); United States v. Rivera-Morales, 166 F. Supp. 3d 154, 163-68 (D.P.R. 2015); O’Leary v. Secretary, No. 2:12-cv-599-FtM-29CM, 2015 WL 1909732, at *20 (M.D. Fla. Apr. 27, 2015); United States v. Kaszynski, No. 2:14-cr-13-FtM-29DNF, 2014 WL 5454324, at *12-15 (M.D. Fla. Oct. 27, 2014); DeGeorgis v. State, No. A16A0927, 2016 WL 6134087, at *2 (Ga. Ct. App. Oct. 20, 2016); State v. King, 2014 WL 6977826, at *5-6 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. Dec. 11, 2014).

Recognition of the inapplicability of Jacobsen to Jones searches has the potential to impact currently pending cases. See, e.g., State’s Brief on the Merits After Granting of Discretionary Review, State v. Rodriguez, No. PDR-1391-15, 2016 WL 1532547, at *42-44 (Tex. Crim. App. Apr. 12, 2016) (arguing for application of the private search doctrine to the search of a dorm room).

See, e.g., Ricardo J. Bascuas, The Fourth Amendment in the Information Age, 1 Va. J. Crim. L. 481, 487 (2013); J. Bryan Boyd, Arrested Development in Search Law: A Look at Disputed Consent Through the Lens of Trespass Law in a Post-Jones Fourth Amendment—Have We Arrived at Disputed Analysis?, 46 Seton Hall L. Rev. 1, 6-8 (2015); J. Amy Dillard, Big Brother Is Watching: The Reality Show You Didn’t Audition For, 63 Okla. L. Rev. 461, 471 (2011); Kevin Emas & Tamara Pallas, United States v. Jones: Does Katz Still Have Nine Lives?, 24 St. Thomas L. Rev. 116, 118 (2012).

See id. at 89 (“[P]erhaps . . . [the] characterization [of the prior law as a law of trespass] provided a straw man useful to justify departing from precedent [in Katz].”); Bascuas, supra note 10, at 487; Dillard, supra note 10, at 471-72 (“Katz is offered in textbooks as a starting point for the ‘expectation of privacy’ doctrine that has permeated constitutional criminal procedure in the last forty years.”).

Kerr, supra note 11, at 68 n.5; see also Emas & Pallas, supra note 10, at 147 (“In justifying the conclusion that the installation and use of the GPS device was a search, Justice Scalia climbs into a jurisprudential time machine, resuscitating cases that had been viewed by many as the jetsam of modern Fourth Amendment jurisprudence.”).

See generally, e.g., Stephen LaBrecque, Comment, “Virtual Certainty” in a Digital World: The Sixth Circuit’s Application of the Private Search Doctrine to Digital Storage Devices in United States v. Lichtenberger, 57 B.C. L. Rev. E. Supp. 177 (2016) (analyzing a recent decision under Jacobsen from a privacy perspective without exploring the implications of Jones for the private search doctrine); Katie Matejka, Note, United States v. Lichtenberger: The Sixth Circuit Improperly Narrowed the Private Search Doctrine of the Fourth Amendment in a Case of Child Pornography on a Digital Device, 49 Creighton L. Rev. 177 (2015) (same).

See, e.g., Matejka, supra note 34, at 192-93 (arguing that the private search doctrine, as applied to digital storage devices, “strikes the proper balance between information the government may gain from their search and individuals’ reasonable expectation of privacy in their digital media storage” because “[i]f the police must have virtual certainty of what is contained on the device, they are thus not blindly fishing for information on a device for which they do not have a warrant”). My goal here is not to defend Jacobsen’s application to Katz searches, but merely to suggest that whatever can be said in favor of Jacobson as it currently exists does not apply to Jones searches. For a rejection of the private search doctrine under a state constitution’s conception of privacy, see State v. Eisfeldt, 185 P.3d 580, 585-86 (Wash. 2008).

See, e.g., LaBrecque, supra note 34, at 182 (“Once the container has been opened by a private party, the owner’s expectation of privacy in the container’s contents has been frustrated.”); see also Bascuas, supra note 10, at 511-15 (using Jacobsen as an example of how the switch from trespass to privacy theories of the Fourth Amendment reduced the protections the Fourth Amendment affords). The secrecy-focused conception is distinguished from conceptions of privacy in which privacy interests are specific to the person who learns the information, so that privacy frustrated as to one person is not frustrated as to other people. See Eisfeldt, 185 P.3d at 585-86.

The Jacobsen court acknowledged this point, and held merely that the additional information gained was not information in which the defendant had a reasonable expectation of privacy—a purely Katz-based inquiry. Jacobsen, 466 U.S. at 119 (“The advantage the Government gained . . . was merely avoiding the risk of a flaw in the employees’ recollection, rather than in further infringing respondents’ privacy. Protecting the risk of misdescription hardly enhances any legitimate privacy interest, and is not protected by the Fourth Amendment.”).

See United States v. Lichtenberger, 19 F. Supp. 3d 753, 759 & n.5 (N.D. Ohio 2014) (treating the analysis under Jones separately from the Katz analysis of reasonable expectations of privacy, and applying Jacobsen’s private search doctrine only to the latter), aff’d on other grounds, 786 F.3d 478, 484-85 (6th Cir. 2015).

See Tenet v. Doe, 544 U.S. 1, 10-11 (2005) (“[I]f the ‘precedent of this Court has direct application in a case, yet appears to rest on reasons rejected in some other line of decisions, the Court of Appeals should follow the case which directly controls, leaving to this Court the prerogative of overruling its own decisions.’” (quoting Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shearson/American Express, Inc., 490 U.S. 477, 484 (1989))).

See United States v. Maldonado-Espinosa, 767 F. Supp. 1176, 1186 (D.P.R. 1991) (“The ubiquitous warrantless airport X-ray is a search for purposes of the Fourth Amendment. It is justified as an administrative procedure, an exception to the warrant rule tolerated as necessary to insure safety in air travel.”).

Professor Ricardo J. Bascuas argues that Jones “preserves the result[] in . . . Jacobsen” because it did not change the “meaningful interference” element of Fourth Amendment seizure analysis, and thus “the federal agents’ handling of [the] package” would not be a seizure. Bascuas, supra note 10, at 524 & n.214. Professor Bascuas’s argument, however, overlooks the implications of Jones’s redefinition of the search inquiry for the result in Jacobsen.