On Estimating Disparity and Inferring Causation: Sur-Reply to the U.S. Sentencing Commission Staff

In our article, we examined the effects of United States v. Booker on racial disparity throughout the federal criminal justice process, using a newly constructed dataset that traces cases from arrest through sentencing.1 Using an econometric method for causal inference, a regression discontinuity-style design, we found no evidence that Booker or its progenyincreased black-white disparity in the sentences received by arrestees with the same arrest offense and underlying characteristics. Nor did we find any substantial increases in disparity in charging, plea-bargaining, or fact-finding. While our causal analysis focused on Booker’s short-term effects, analyses of the longer-term trend also showed that the sentence gap among otherwise-similar black and white arrestees did not grow in the years following Booker. We therefore concluded that there is no evidence that racial disparity has increased since Booker, much less because of it.

Our findings conflicted with the conclusions of two U.S. Sentencing Commission reports. The Commission found that the sentence gap between comparable black and white men had approximately quadrupled in the wake of Booker and its progeny, implied that Booker’s expansion of judicial discretion was the cause of that quadrupling (and of an increase in interdistrict disparity), and accordingly proposed various legislative fixes to reimpose constraints on judicial discretion. We critiqued the methods used by these reports as well as other sentencing-disparity research. In particular, we argued that estimates of sentence gaps should not use control variables that filter out the components of those gaps that arise from decision-making earlier in the justice process. We also argued that the Commission’s method of comparing the time periods before and after Booker and its successors could not support causal inferences about Booker’s effects, because it could not disentangle those effects from background trends and events.

The Commission’s empirical staff members—the authors of the prior reports—have now published a reply.2 We appreciate their taking the time to engage with these issues, and also appreciate the Commission’s longstanding efforts to understand sentencing disparities. We wholeheartedly agree that racial disparities exist in the federal system and are troubling. However, we believe that designing effective policies to address unwarranted disparities requires rigorous identification of their causes, and we believe the Commission’s approach falls short of this mark. Not everything that has happened in sentencing since 2005 is the result of Booker. We also believe that the potential sources of sentence disparity begin far earlier in the process than the judge’s final sentencing decision, which is the focus of the Commission’s analysis. Booker altered the legal landscape for prosecutors, defendants, and judges, and one cannot get a complete picture of its effects on disparity by only comparing pre- and post-Booker disparities in the last narrow slice of the criminal justice process.

The reply unfortunately contains a number of mischaracterizations of our findings and approach. For example, the reply repeatedly suggests, beginning with its title, that we have claimed that judges don’t “matter at sentencing.” But to the contrary, our method examines changes in judicial behavior far more comprehensively than the Commission’s does, and also examines changes in the behavior of other important actors who also matter. While the Commission repeatedly claims that we have ignored the “reality of the actual sentencing process,”3 and in particular that we have disregarded the legal and practical importance of the determination of the Guidelines sentencing range, in fact it is the Commission’s approach that effectively disregards the importance of that process by excluding any disparities that arise in it from its ultimate sentence disparity estimates. Our approach, by contrast, takes each stage in the justice process seriously (including Guidelines fact-finding) by assessing Booker’s effects ondisparities in all of them, individually and in the aggregate. In short, we do not ignore variables like the presumptive Guidelines sentence; we treat them as outcomes to be analyzed, rather than controls to be filtered out.

In addition, the reply frequently appears to confuse the main results presented in our article—our study of Booker’s effects—with our separate study of federal charging disparities, which we briefly summarize and discuss in Part II of our article. For example, the reply repeatedly alleges that we exclude drug cases.4 This was true of many (but not all) of the analyses in our charging study, but it is not true of the Booker study: the Booker study’s sample includes all major case categories other than immigration, as the article makes clear. The reply’s focus on the other study is curious, because it is the Booker study thatmost directly relates to the Commission’s own reports. In its comparatively limited discussion of Booker, the reply seems to retreat from the claim that the Commission’s findings can be interpreted causally, and states that identifying causation is unimportant.5 But without evidence that Booker caused an increase in racial disparity, racial disparity does not justify policy proposals designed to reverse Booker’s effects.

This sur-reply is organized in four parts. First, we briefly summarize our study’s methods and findings. Second, we consider the reply’s critique of our decision to explore disparities arising from earlier procedural stages rather than only considering the sentencing stage in isolation. Third, we address the causal inference issue and the criticisms of our regression discontinuity approach. Fourth, we show that the reply’s criticisms pertaining to the definition of our sample are unsound, and that several of them are simply inapplicable to the sample used in this study.

I. Our Study of Booker’s Effects

The principal results reported in our article stem from a study of changes in black-white racial disparities in federal cases, excluding immigration, during the time period surrounding United States v. Booker. We constructed a unique dataset that combined records from four federal agencies, allowing us to trace cases from arrest through sentencing. By controlling for arrest offense characteristics and other prior traits (such as criminal history), we were able to compare black and white arrestees whose cases looked similar when they entered the federal justice system, and estimate the divergence of their fates at each subsequent stage of the justice process as well as Booker’s effects on disparities at all those stages. Because the pre-sentencing stages have crucial consequences for the sentence,6 we believe that understanding them is essential to assessing Booker’s impact on racial disparities in ultimate sentence outcomes. Unlike the Commission’s alternate approach, which we discuss further below, we therefore did not use control variables that filter out the share of the sentence gap that arises from those earlier stages.

Our first cut of our data, presented in Table 1 of our article, was a description of the long-term linear time trends in the black-white sentence gap over the period from May 2003 through September 2009 (a period that directly corresponded to the period during which the Sentencing Commission’s 2010 report had found that disparity among black and white males had more than quadrupled, from 5.5% to 23%). Our assessment of these long-term trends did not speak to Booker’s causal effects—as we explain below, it is dangerous to attribute long-term trends to a single intervening event. Instead, this estimation was simply designed to assess whether racial disparities for comparable individuals arrested for the same offense did, in fact, grow during the study period.

We found that they did not. Note that our claim is not that racial disparity is not a problem, but rather that the problem has remained fairly stable in scale. One only finds an upward trend in disparity if, like the Commission, one focuses on the final slice of the justice process in isolation—excluding the portions of the sentence gap that come from all of the earlier procedural stages. We also found that black-white disparity in the Guidelines offense level (and thus in the “presumptive sentence,” which is based on that offense level combined with criminal history) declined during the same period, conditional on the arrest offense and other prior traits. This change provides one plausible explanation for the difference between our findings and the Commission’s. The Commission is measuring sentence gaps relative to the presumptive sentence, but if racial disparity in the presumptive sentence itself declines (holding underlying conduct constant), a gap measured this way will appear to grow even if final sentences themselves are actually unchanged. This apparent growth is an artifact of the Commission’s estimation strategy—it does not mean that disparity actually got worse among defendants with similar underlying conduct.

Next, we turned to the question of Booker’s causal effects on disparities at each key stage of the process. The question whether Booker (and its progeny, United States v. Gall and United States v. Kimbrough)caused changes in racial disparity is quite different from the question whether racial disparity was larger after those cases were decided. Many things change over time. If disparity simply grew over time due to gradual background trends or events unrelated to Booker, disparities would appear larger in the post-Booker and especially the post-Gall/Kimbrough periods, just as the Commission found.

To assess Booker’s causal effects rigorously, we used a regression discontinuity-style estimator (RD), which filters out background trends and focuses on sharp breaks in disparity occurring immediately after Booker. We applied this method to assess changes in each of the major procedural stages (charging, plea-bargaining, and sentencing) by exploiting the fact that criminal cases have several key moments. We thus assessed changes in initial charging (and their consequences for downstream outcomes, including the ultimate sentence) by looking for sudden changes as the charging date passed Booker. Similarly, we assessed changes in plea-bargaining and in sentencing (including fact-finding) via analyses that turned on the dates of conviction and sentencing, respectively. The specific results are detailed in our article (including in Table 2) and will not be repeated here, but the upshot is that there is no evidence that Booker caused increases in racial disparity in any aspect of the judicial process.7 While our main analyses focused on Booker for reasons explained in our article, we also found no notable changes in racial disparity in the aftermath of Gall/Kimbrough.

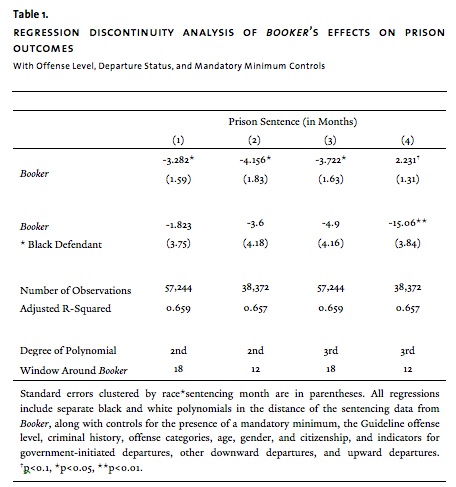

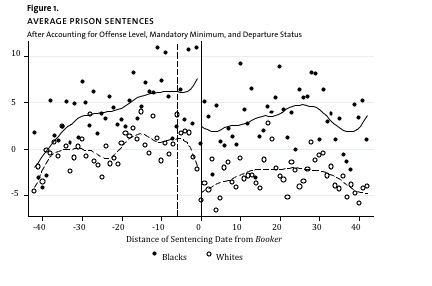

Our article did not include an RD analysis that parallels the Commission’s approach to estimating disparity—that is, one that assesses whether, immediately after Booker, there were sharp changes in sentence disparities when one controls for the presumptive sentence, the mandatory minimum, and departure status. We still do not favor this method, but for comparative purposes, we have now carried out an additional analysis that applies the RD method detailed in our article, but uses a set of control variables closely paralleling the Commission’s. Specifically, we repeated the regressions shown in Table 2, Panel 3C of our article (estimating the prison sentence outcome by sentencing date), but altered the control variables. We removed our arrest-offense controls and replaced them with the Guidelines offense level,8 the mandatory minimum indicator, broad offense-category controls similar to the Commission’s, and indicators for the existence of government-initiated downward departures, other downward departures, and upward departures. The results are shown in Table 1 and visually depicted in Figure 1 (which, like the figures in our article, shows monthly averages for black and white residual sentences after the portions explained by the controls are removed).

This additional analysis shows no increase in black-white sentencing disparity in cases sentenced after Booker. Indeed, in all four specifications the estimated change in disparity at Booker is negative, although this reduction is significant and sizeable in only one of the four specifications.9 Figure 1 likewise shows that while sentences (after controlling for these variables) fell overall after Booker, this change affected black and white defendants approximately equally. There is no discernible increase in disparity: the distance between the white and black lines does not grow. The beginning of the fall in sentences for white defendants actually appears to predate Booker. That is, even when one estimates disparity the Commission’s way (but uses a proper method for causal inference), Booker does not appear to have increased it.

II. Should Sentence Disparity Estimates Incorporate Multiple Procedural Sources?

The first fundamental difference between our approach and that of the Commission’s reports (as well as other existing literature) pertains to the way disparity is estimated. We control for the arrest offense and other prior characteristics, while the Commission controls for a set of variables including the “presumptive sentence” (the low end of the Guidelines range), the mandatory minimum sentence, and indicators of whether and in what direction the judge chose to depart from the Guidelines. Disparity estimates using the Commission’s controls filter out disparities in charging, plea-bargaining, sentencing fact-finding, and even the judge’s departure decision. Once one has already controlled for the existence of a departure, its direction, and the point from which the judge considers departing (the presumptive sentence), disparities that remain presumably must mainly be driven by disparities in departure magnitude and disparities in the choice of sentence within the guidelines range.

The Commission’s approach reflects a very narrow definition of what sources of disparity policymakers should care about when assessing Booker’s effects. The choices made at the earlier procedural stages have sentencing consequences, and the Commission’s estimates filter out those consequences. Moreover, the variables the Commission controls for could have been changed by Booker itself or by other trends and events in the years covered by the study. If, for instance, prosecutors used mandatory minimums differently in the later years, fact-finding changed, or judges departed more often, these control variables would not have the same relationship to underlying criminal conduct before and after Booker, and those changes might not affect black and white defendants equally. This makes it difficult to compare estimates of sentence disparity for the different time periods.

As our article discusses, what constitutes an appropriate method or control depends upon the goal of the analysis. We are especially concerned with the ultimate disparity in sentence outcomes for black and white offenders who had similar criminal conduct, criminal history, and other prior traits—so those characteristics are what we aim to control for, using arrest offense as the best possible proxy for criminal conduct. We thus measure disparities arising at each stage of the justice process, which could compound or offset one another. We think the objective of equal treatment generally demands a process-wide approach, because sentence inequalities for similar offenders are troubling whether they arise in charging, plea-bargaining, fact-finding, departure decisions, or the ultimate choice of sentence.

And indeed, this point was eloquently stated by the Sentencing Commission itself in a report it released in 2004, the year before Booker.10 In that report, the Commission carefully explained the serious limitations of an approach to sentence-disparity analysis that focused only on disparities in the final sentencing decision “in isolation.”11 It cited “a variety of evidence,” including surveys and qualitative studies, suggesting “that disparate treatment of similar offenders is common at presentencing stages.”12 The report concluded that such earlier-stage disparities would have important sentencing consequences, especially in light of the presumptive Guidelines system that then existed, under which “there is little a judge can do to compensate” for charging disparities.13 The Commission explained that it focused only on sentencing (using the presumptive sentence approach) only because of limitations in its data, which did not cover the earlier stages in the process.14 Its approach thus by necessity defined “uniformity” in a very specific, limited way: “similar treatment of offenders who appear to be similar[] based on the charges of conviction and the facts established at the sentencing hearing.”15 The Commission forthrightly acknowledged that “uniformity” in this narrow sense was not all that one might aspire to: “Achievement of the more ambitious goal of similar treatment of offenders who engage in similar real offense conduct will also depend on uniform treatment at presentencing stages.”16

Because we now have the data the Commission lacked, our research has been able to fill the need for a broader approach that the Commission so effectively pointed out in 2004. Perhaps the Commission’s perspective on what disparities matter has changed over time. In fairness, that perspective might properly be different from ours, because the Commission is an institution tasked with creating the Sentencing Guidelines and encouraging judges to use them; there are reasons for it to focus on disparities in judges’ divergence from the Guidelines. The question is whether this is the relevant disparity for Congress or other decision-makers to consider, given that they do not necessarily share the Commission’s institutional focus. We do not claim that studies focusing only on judicial sentencing-choice disparities tell us nothing useful—this stage is an important part of the process. But as other researchers using such approaches have often acknowledged,17 they provide only a piece of the picture of criminal justice disparities. Our work complements such studies by offering a more complete view, allowing policymakers to assess Booker’s effects across the justice process.

But even if, like the Commission, one is particularly interested in disparities in Guidelines compliance, it is problematic to control for the existence and direction of a Guidelines departure (or variance). The decision whether to sentence outside the Guidelines at all is likely to be just as important a source of disparity in Guidelines compliance as the decision of how far outside the Guidelines to go. The use of the departure controls is especially a problem for a study assessing Booker’s effects. Booker legally authorized Guidelines departures that would not otherwise have been permitted, and its one unambiguous, large effect on sentencing practice was that it caused a dramatic, immediate increase in departure rates.18 A study cannot assess Booker’s effects, even on sentencing relative to the Guidelines, if it filters out the aspect of the sentencing decision that Booker changed most dramatically.19

The reply states that our study “ignore[s] the process judges actually use,”20 that it is not “based on the reality of the sentencing process,”21 that we “disregard the presumptive sentence,”22 and that we “omit consideration of the sentencing guidelines.”23 With respect, the opposite is true. We fully agree that the determination of the Guidelines range, as required by law, is a crucial part of the sentencing process. This is precisely why we believe that estimates of sentence disparity should include racial disparities that arise in the processes that determine the Guidelines range (which include both plea-bargaining and judicial fact-finding). In contrast, including the presumptive sentence in the regression, as the Commission favors, means that disparities in the sentence that result from those processes are excluded from the racial disparity estimate. Likewise, controlling for the mandatory minimum and departure status excludes the portion of sentencing disparity that comes from the processes that determine the mandatory minimum and from the judge’s decision whether to depart.

The reply contests this point, stating: “Rather than ‘filtering out’ a key part of the sentencing decision, as Starr and Rehavi assert, our model controls for the different steps in the process.”24 This comment risks confusing readers as to what a control variable does. Control variables filter things out: specifically, they remove from the estimate of racial disparity in the sentence the component of that disparity that is explainable by the controls.25 It is not always better to control for more factors—especially not factors that are actually part of the phenomenon you are interested in measuring.26

In contrast to the Commission’s narrow approach, our estimates of total black-white sentence disparity incorporate the sentencing consequences of all of the post-arrest steps in the process. However, not all of our analyses aggregate these steps. Table 2 of our article also shows separate analyses of Booker’s effects on the individual steps in the process, showing, for instance, its effects on disparities in the final Guidelines offense level, in departure rates, and in mandatory minimum charging and conviction rates. Our results also excluded government-initiated departures (but, as we pointed out, would have been the same had we included them), addressing another of the Commission’s concerns.27

Contrary to the reply’s assertions, we do not suggest that judges do not “matter at sentencing.”28 We do not embrace any “notion that judging in the federal system is limited largely to picking a sentence from a table after adding up a numerical score.”29 Nor do we doubt that “judges are very concerned with determining the fair sentence and assess all of the evidence presented to them with a discerning eye”—although the parties do shape what evidence is presented to the judge.30 Moreover, although the importance of prosecutorial decision-making was one motivation for our research, we do not assume that “prosecutors alone principally determine the sentences imposed.”31 Indeed, unlike the Commission, we assume nothing about which of the post-arrest justice stages are the most important—that is why we study Booker’s effects on all of them. And far from ignoring judges, our approach more effectively captures judges’ sentencing-stage contributions to disparity because our estimates incorporate differences in departure rates and sentencing fact-finding. The Commission’s approach, in contrast, filters out those differences, narrowly focusing on a small slice even of what judges do.

Finally, the reply sets forth some limitations of our key control variable, the arrest offense.32 We do not claim that the arrest offense is a perfect proxy for conduct, nor that the presumptive sentence never captures nuances in conduct that the arrest offense misses.33 We pointed out these same limitations in our article, and explained why we nonetheless believe the arrest data provide, on balance, better information for our purposes about underlying conduct than the presumptive sentence does.34 The article also explains that the hundreds of arrest offense codes provide far richer data on crime type than the Commission’s seven broad categories do.35 We will not repeat these analyses here.

But one point worth emphasizing is that none of the arrest data’s limitations particularly matter for the purpose of our analysis of Booker’s effects. A major advantage of RD is that, unlike basic regression, it does not depend on the assumption that one has successfully observed and controlled for all of the differences that could confound the underlying disparity estimates. This is because the objective of the analysis is to estimate the change in disparity at Booker—not the underlying level of disparity—and that change can be validly estimated even if there are omitted variables. The assumption underlying our RD analysis is simply that cases immediately on either side of the discontinuity were comparable with respect to any omitted differences.36 Put another way, even if the model omits differences between black and white cases, the discontinuity estimate will not be biased so long as the relative underlying, unobserved severity of black and white cases did not suddenly change at Booker. Take, for instance, the possibility that loss amounts in fraud cases vary by race, a difference our arrest codes cannot capture.37 So long as the relative loss amounts involved in black versus white defendants’ cases do not suddenly change, breaking from ongoing trends, in the vicinity of Booker, the estimates for Booker’s effects on racial disparity in sentencing and other outcomes would be unaffected.

Control variables serve a different function in regression discontinuity design than they do in basic regression analyses like the Commission’s—in RD they mainly absorb noise. If the control variables do not suddenly change in the vicinity of the discontinuity, the RD estimates should be approximately the same whether or not they are included.38 And indeed, we ran all our RD analyses with and without controls and got similar estimates. This is because there is no reason to believe that the underlying pools of cases resulting in federal arrests, or the Marshals Service’s coding of those cases, changed suddenly right around Booker, much less in racially disparate ways.In contrast, it would be problematic to include in the RD analysis control variables that could be affected in the short term by Booker itself, and thus it is important that we do not control for the presumptive sentence, departure status, or mandatory minimum. Instead, we conduct separate RD analyses of each of these as outcome variables, to investigate whether they were affected by Booker.

III. The Reply’s Comments on Our Booker Analysis

The objective of our article was to evaluate the causal effects of Booker on racial disparity. The reply suggests that the Commission had a different objective, seemingly backing away from a causal interpretation of the Commission’s findings. Indeed, it suggests that causal identification is not important:

| We do not think it important to say (or to disprove) that Booker, or Kimbrough and Gall, alone caused the differences we find. Rather, we think it is more important to note that demographic differences in sentences existed to a much larger extent after those decisions than immediately before them and that policymakers, judges, and the Commission should consider this fact.39 |

We respectfully disagree. Causal identification is important in order for policymakers, judges, and the Commission to know what to make of disparities, and to inform their decisions about what solutions, if any, to pursue. Even if disparities did exist to a much larger extent after Booker and its progeny, if the court decisions did not cause the growth in disparity, then disparity would not be a reason to adopt policy measures paring back Booker’s effects on judicial discretion. The Commission itself titled its 2012 Report “Report on the Continuing Impact of United States v. Booker on Federal Sentencing,” implying a causal connection, and that report contains policy recommendations that are premised on the notion that there is a Booker problem that needs to be fixed. Our RD analyses showed that, at least where racial disparity is concerned, there is no evidence that Booker created a problem.

As Section III.A of our article detailed, the Commission’s approach does not yield valid causal inferences about Booker’s effects. Its method is to compare the estimates from separate regressions conducted on sets of cases from several separate time periods—most notably, the periods from the PROTECT Act to Booker, from Booker to Gall/Kimbrough, and the post-Gall/Kimbrough period. Because the “black” coefficient is smallest in the first (5.5%) of these three periods and largest in the last (19.5%), the Commission implies that disparity increased in response to Booker and its progeny.40

However, one cannot safely attribute differences in the average disparities measured in these broad time periods to a single intervening legal event. Many things can change over time, any of which could explain these results. Differences between the periods before and after an event do not necessarily result from the event. It is colder in North America during the two months after December 25 than during the preceding two months, but one cannot therefore infer that the exchange of Christmas gifts by many families caused winter. Similarly, racial disparity as the Commission measures it could have been higher in the later time periods for reasons unrelated to Booker. For example, even if judicial behavior did not noticeably change, the composition of the pools of cases in the three periods might have been different, with the later pools involving more cases with characteristics that tend to produce greater racial disparity.41

Moreover, another serious threat to causal inference is the possibility that the presumptive sentence and the problematic control variables might have changed in response to Booker,or otherwise changed over time, in ways that are not explained by changes in underlying criminal conduct. For instance, if fact-finding disparities were declining over the period (as Table 1 of our article suggests), the presumptive sentence control might effectively mean something different in the later time periods than it did in the earlier time periods, relative to underlying conduct. This would mean that racial disparity estimates that condition on the presumptive sentence could not fairly be compared across time periods—the presumptive sentence has become a different “yardstick” for measuring the severity of conduct.42

In response to these criticisms, the reply offers a description of a new analysis that its authors conducted, which replicates the Commission’s separate regressions but reduces the time periods being compared to three six-month periods: just before Blakely v. Washington, between Blakely and Booker, and after Booker. The reply states that disparity increased from each period to the next, although the size of the increase is not stated. This reduction of the time periods’ length is a welcome modification, but this new analysis does not resolve the causal inference concerns. The shorter periods do not solve the problem that the presumptive sentence or other control variables could have been affected by Booker (or Blakely), creating a “changing yardstick” problem. Moreover, the eighteen-month period on which this new analysis focuses, while less problematic than the original, longer periods, is still long enough that background trends or other events could confound the results. Our regression discontinuity approach, in contrast, controls for those background trends so that it can separately identify sharp breaks in the trends.43

In addition, the findings of the reply’s new analysis do not actually seem to support the conclusion that Booker increased disparity. The reply finds that the increase in disparity (as the Commission measures it) began before Booker,in the period surrounding Blakely.44 The reply contends that these new findings show that “the impact of Booker . . . may have begun even before the date of that decision,” namely, with “the decision in Blakely, a case with a holding very similar to Booker but which applied only to state court cases.”45 The implication of this argument is that the post-Booker sentencing-procedure regime, on which the Commission blames the increase in disparity, actually began not with Booker but with Blakely. But this interpretation is implausible. While Blakely’s Sixth Amendment holding was indeed similar to Booker’s, its remedy was not; it did not loosen constraints on judicial discretion. No circuit adopted a Booker-like remedy during the period between Blakely and Booker, and the Guidelines remained mandatory in every federal court. Nor did district courts begin acting as though their discretion had expanded. As shown in Figure 1 of our article, there was no rise in departure rates after Blakely—until Booker, when they immediately spiked.

Blakely might well have changed the incentives and actions of the parties, and in some courts it likely changed fact-finding, because certain circuits began to require aggravating facts to be proven to juries. These possibilities are the reason we confined our Booker analysis to the “business as usual” circuits and carried out other assessments of Blakely’s effects. But the Commission’s measure of disparity does not focus on the parties, nor on fact-finding; it focuses only on judicial sentencing relative to the Guidelines. The increased disparity it finds before Booker cannot be attributedto judges’ expanded discretion, because that discretion did not expand until Booker was decided.46 Instead, the Commission’s new analysis is consistent with the theory that the increased disparity it found after Booker was the result of an unrelated background trend.

In contrast to the Commission’s methods, our regression discontinuity-style approach is a rigorous method for estimating causal effects, and provides no evidence that Booker increased disparity. The reply critiques our focus on Booker’s short-term effects, attributing to us the straw-man position “that the full impact of Booker would be seen in the weeks or months immediately after Booker.”47 Our article makes clear that we do not believe this is true, but also explains that it does not need to be true for regression discontinuity analysis to nonetheless tell us something important about Booker’s causal effects.48 It is not that we should expect Booker’s full effects to have been seen right away—it is that, if one is to infer that Booker dramatically increased racial disparity, one should expect to see some of that effect immediately after Booker. After all, Booker did have a dramatic, immediate, discontinuous effect on judges’ willingness to depart from the Guidelines.49 If judges used their newfound departure authority in ways that disproportionately benefited white defendants or harmed black defendants, one would expect at least some of that disparate effect to appear fairly quickly, given that they started using that authority right away. But it did not. Nor, for that matter, were there any sudden increases in disparity after Kimbrough and Gall.50 Moreover, our estimation of the long-term trend also failed to find an increase in disparity.

Of course, as we observe in our article, it would be wonderful if Booker’s long-term causal effects could also be analyzed in a rigorous way. Unfortunately, this is not possible. The methods the Sentencing Commission uses cannot do it, and we are pleased that the reply essentially acknowledges this point.51 Too many things change over time. The best that can be done is to assess the short-term causal effects using RD—and the RD analyses do not find an increase in disparity. Moreover, again, our analysis of the long-term trends (which we do not claim are causally linked to Booker) also fails to find an increase in disparity, and, if anything, suggests a decline.

IV. Our Sample

The reply repeatedly criticizes our study’s sample, contending that it represents only a narrow subset of federal cases during the relevant period. First, it is false that our sample excludes drug cases,52 or that it otherwise consists of a narrow subset of crimes.53 As our article clearly states, the sample for the RD analysis “includes all non-immigration cases except identity theft, which was subject to other major sentencing-law changes very near Booker.”54 Notwithstanding the article’s repeated clarifications of this point,55 the authors appear to be confusing our article’s study of Booker with the separate study of charging disparities that we summarized in Part II; that study had excluded drug cases from some, but not all, of the analyses, and the alternative analyses that did include them found similar disparity patterns.56 Likewise, the Booker study is obviously not limited to “data only from fiscal years 2007 to 2009.”57 Nor does the Booker study exclude non-U.S. citizens, contrary to the reply’s claim.58

It is true that we include Hispanic offenders in the black and white groups in some of our analyses.59 Hispanic persons can identify with various racial groups, and there is no reason that disparities between black and white Hispanics should not count as black-white racial disparity. In any event, however, the results of our RD analysis, as we explained in the article, were unchanged if we instead exclude Hispanic defendants, focusing on the gap between non-Hispanic white and black defendants.60 Our analysis of the long-term trends from 2003 through 2009 (Table 1 of our article) was designed to track the Sentencing Commission’s sample as closely as possible, except for the exclusion of immigration cases. It therefore excluded Hispanic defendants and focused only on black and white non-Hispanic men.61 When Hispanic defendants are included instead, estimates of the decline in disparity over that period are somewhat larger and statistically significant, as our article explains.62

The one truly substantial difference between our sample and the Commission’s concerns immigration cases. Immigration cases are a big part of the federal docket (although they are, in fact, quite a small part of the black-white incarceration disparity picture).63 But there are good reasons that we, like many other researchers, excluded them. First, changes in immigration cases could very well be an example of a strong background trend during the study period that confounds the Commission’s results. While the volume of non-immigration cases was fairly stable, the number of immigration arrests recorded in the Marshals Service database more than tripled from 2003 to 2009, from approximately 25,000 to approximately 85,000. The number of sentenced immigration defendants in the Sentencing Commission’s dataset also increased substantially, but not quite as dramatically, from approximately 14,000 to approximately 24,000. Thus, at least two changes seem to have been underway during that period. First, there was an explosion in the immigration caseload. Second, there were also very likely changes in the way many of the cases were being processed, such that many more cases did not proceed to sentencing on a non-petty offense at all, or at least were greatly delayed such that they did not do so within the studied time period. If one is attempting to assess Booker’s effects by looking at changes across a time period, it is risky to include a huge category of cases that was so transformed during that period. Indeed, if disparities are higher when immigration cases are included than when they are not (as an alternative analysis by Jeffrey Ulmer, Michael Light, and John Kramer concluded),64 the growth in immigration’s share of the federal caseload during the Commission’s study period could explain why the Commission observed higher disparities in the later periods. But that explanation is not related to Booker. It is an example of the type of unrelated trend that the Commission’s method cannot rule out.

Second, immigration cases differ from other cases both procedurally (they are often subject to fast-track processing) and substantively: for almost all offenders, their stakes turn in substantial part on deportation. The reply is correct that most immigration offenders also serve a short prison sentence.65 But deportation is inarguably a critical partof the outcome for most offenders, and to compare the severity of outcomes in immigration cases on the basis of incarceration alone is potentially misleading.

The Commission also observes that our sample lost some cases due to inability to link them across agencies.66 This is true, but link rates at every stage were quite high,67 and we conducted analyses that found no racial disparities in link rates, suggesting little reason to believe that the algorithm’s imperfections biased the results. We also conducted analyses of Booker’s effects on racial disparities in the rate at which non-petty charges are brought and the rate at which such cases result in conviction, finding none. These analyses were important in order to assess the possibility of sample selection bias, because conviction on a non-petty charge is necessary for a case to make it into the Sentencing Commission’s data. The Commission’s analysis is equally susceptible to these sources of sample selection bias, and yet the Commission did not (and could not, in the absence of other agencies’ data) carry out any analyses of whether the subset of cases that made it into their dataset varied across the different time periods. Indeed, the immigration figures cited above strongly suggest that it did.68

Conclusion

We stand by our conclusion that there is no evidence that Booker and its progeny increased disparity in the sentences of comparable black and white offenders. The Commission’s empirical staff indicate in their reply that causal inference was not the goal of their study; it was, however, the goal of ours. And our regression discontinuity analysis shows no evidence that Booker caused substantial changes in the sentences received by black and white arrestees with comparable arrest offenses and characteristics, nor does it show any clear evidence that Booker caused an increase in disparity in any specific stage of the judicial process. Moreover, longer-term analysis shows that in the years surrounding Booker, there was no increase (there was possibly a slight decline) in sentence disparity for comparable black and white arrestees. The Commission’s contrary findings appear to be driven not by changes in sentencing, but by a trend of decliningdisparity in its key control variable, the presumptive sentence, along with other potential confounders. This point illustrates the wisdom of the warning the Commission itself issued back in 2004: analyzing sentencing disparity in isolation from other parts of the justice process risks missing an important part of the picture.

We do not wish to minimize the concern of racial disparity in the justice process. Indeed, our work has emphasized the importance of this concern, exploring prosecutorial charging discretion as an important mechanism behind racial disparity. But the problem, while persistent, does not appear to be growing, nor does it appear to be the result of expanding judicial discretion. And if expansions of judicial discretion did not cause an increase in disparity, re-imposing constraints on that discretion may not be a solution.

Sonja Starr is a Professor of Law at the University of Michigan. Marit Rehavi is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of British Columbia and a Fellow of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.

Preferred citation: Sonja B. Starr & M. Marit Rehavi, On Estimating Disparity and Inferring Causation: Sur-Reply to the U.S. Sentencing Commission Staff, 123 Yale L.J. Online 273 (2013), http://yalelawjournal.org/forum/on-estimating-disparity-and-inferring-causation.