J. Crew, Nine West, and the Complexities of Financial Distress

abstract. The law-and-economics literature assumes that omnisciently rational “sophisticated parties” write optimal contracts, making bankruptcy law unnecessary. Two case studies, J. Crew and Nine West, illustrate the limitations of this idealized model. We argue for a theory of debt contracting based in bounded rationality that recognizes bankruptcy’s inherent complexity.

Introduction

The J. Crew 2014 Amended and Restated Credit Agreement is a complex contract. It is 101 pages and over 87,000 words long. Section 7.02 of the document—one that its lenders came to regret—lists twenty-one carve-outs describing classes of permitted investments. This section alone contains thirty-two cross references to other sections of the same document and forty-four defined terms.

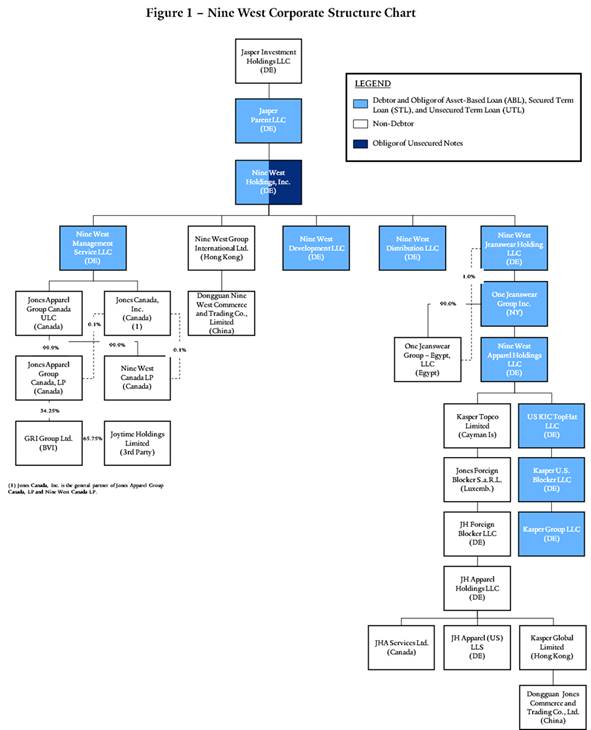

Contracts like these are embedded in capital structures that are also complex. The corporate group that owned Nine West listed twenty-nine different legal entities and seven funded loan facilities and notes.1 Its reorganization plan listed eighteen classes of claims and interests. Most of our corporate-finance theories, by contrast, involve one borrowing entity, no more than two classes of debt, and contracts that can be fully described in a sentence or two. Is the complexity of real-world financial structures and contracts important to a theory of restructuring and bankruptcy? Or are the simplifications we make—a necessary element of all modeling, to be sure—something we can safely set aside?

The law-and-economics approach to corporate bankruptcy is missing something important by ignoring the complexity of real-world contracts and capital structures. In particular, post-financial-crisis restructurings bring to light the main flaw in our existing theoretical framework: the assumption of omniscient2 rational actors known in the law-and-economics literature as “sophisticated parties.”3 Sophisticated parties have a complete and correct understanding of all future contingencies and all possible contractual responses to them.4 The contracts they write are thus always optimal contracts. Capital structures in these models—even when they consciously involve multiple creditors—become globally coordinated mechanisms between firms and their creditors, set up to minimize managerial agency costs.5

When models of this kind are taken to their logical conclusions, bankruptcy law has no valuable role to play.6Even the automatic stay—the mandatory element of bankruptcy law intended to stop a creditor run—is merely an impediment to efficient contracting. After all, if sophisticated parties really want to stay creditor collection, they could set up a contractual device to achieve it on their own.7 If they choose to contract out of it, a creditor run must be a consciously designed mechanism intended to reduce the firm’s cost of capital.8 Many corporate-finance models also implicitly adopt this perspective, assuming that bankruptcy is a procedure that imposes a deadweight cost on the firm but adds no affirmative value.9

Normative analysis of bankruptcy properly insists upon a principled approach to the law that includes ex-ante contracting incentives. But a growing body of empirical literature on commercial contracting casts doubt on the omniscient actor/optimal contracting framework as the proper foundation for this analysis. Contracts drafted by the most sophisticated parties are, nevertheless, imperfect. Parties leave gaps in contracts when terms readily exist.10 Substantive choices of contract terms are path dependent and affected by the law firm that provides the first draft,11 not just the economics of the transaction. And contractual “black holes” can persist for years without correction, as issuers insist on having market terms in their securities even when they know those terms are undesirable.12 Sometimes, these imperfections are of minor importance and can be swept under the rug. But as we will show with two case studies (J. Crew and Nine West), these dynamics are crucial to understanding modern restructuring trends and have important efficiency consequences.

The prospect of interaction between contracts when there is not enough money to go around creates a search for loopholes and other creative strategies. Sophisticated parties do play a crucial role in the story, but it is the opposite of what we typically assume. Sophistication does not result in optimally drafted contracts. Instead, it magnifies the impact of a contract’s inevitable flaws. Sophisticated parties use these flaws to reallocate value from one coalition to another. Restructuring transactions add complexity to capital structures due to new layers of debt and legal entities, as well as the prospect of costly litigation exploiting ambiguous provisions in law and contract. Capital structure changes that occur in such scenarios have little to do with controlling managerial agency costs: they are workarounds of the contractual and legal constraints on the ground when the restructuring happens. Even small changes to capital structures can affect the dynamics of a bankruptcy case in complex and unpredictable ways.

In this Essay, we discuss two case studies that illustrate these important dynamics, exploring their implications for a richer and more realistic theory of debt contracting and bankruptcy that recognizes its inherent complexity. The first case study, J. Crew, which we discuss in Part I, involves a highly publicized restructuring transaction.13 J. Crew exploited a loophole in a credit agreement to remove intellectual-property collateral from its lenders’ reach to help refinance other debt. With the help of its restructuring advisors, J. Crew found a “trap door” provision that facilitated the transfer of collateral. A closer look at this provision reveals that it was intended to permit J. Crew to invest in overseas subsidiaries and minimize taxes, not to permit the transfer of the lenders’ collateral.14 After the fact, it is obvious that J. Crew’s lenders could have stopped this specific maneuver with a simple change to the contract. Indeed, some subsequent loan agreements did exactly that. But this hardly implies that J. Crew’s lenders intended to permit it, as an omniscient-actor perspective would require.

Based on this case study, we argue for the need to acknowledge bounded rationality in our models of contracting, particularly those used to derive normative implications for bankruptcy law. This is not because we believe that commercial contracting parties are unsophisticated, prone to basic mistakes, or unmotivated by market forces. Instead, it is because the cognitive task of drafting a truly optimal contract is too complex for any real-world actor to achieve. Contracting parties, no matter how sophisticated, cannot possibly imagine and contract to prevent all possible loopholes that other sophisticated parties might exploit.15 More importantly to the study of bankruptcy, parties cannot anticipate all possible interactions between their contract and the multiplicity of contracts and rights it will encounter in financial distress. Bankruptcy law does valuable work in practice when these unplanned conflicts arise.

A second case study, Nine West, which we discuss in Part II, illustrates how capital-structure complexity can make a bankruptcy more costly and contentious. It also illustrates a “butterfly effect,”16 whereby small changes to a capital structure can have large and unanticipated effects in a complex environment. Sycamore Capital Partners acquired Nine West and related fashion brands in a leveraged buyout in 2014. It reorganized its corporate structure in the process, leaving most of the debt with Nine West and spinning out other brands to itself, free of debt. An eleventh-hour decision to add more debt to the deal, and to make this debt senior through subsidiary guarantees, became important in the bankruptcy case. It gave rise to a dizzyingly complex array of entitlement disputes between parent and subsidiary creditors about how to allocate assets and debts across the Nine West entities. These disputes contributed to the exorbitant professional fees incurred in the case that reduced creditor recoveries. The Nine West example illustrates the need to better understand the endogeneity of bankruptcy costs and capital-structure complexity as one driver of these costs.

Parts III and IV discuss implications for the law and economics of bankruptcy. We argue that relaxing the omniscient actor/optimal contract assumption can make way for a more realistic theory of contractual evolution. This flexibility can allow for a richer understanding of how complex contracts relevant to bankruptcy evolve, such as debtor-in-possession (DIP) loan agreements, intercreditor agreements, and restructuring-support agreements. A complexity-based perspective also has the potential to refine our normative framework, while preserving the essential foundations of bankruptcy law as a tool for resolving creditor coordination failures.

I. the j. crew loophole

The basic facts of the J. Crew refinancing transaction are well-known. In 2011, the private equity firms TPG Capital and Leonard Green & Partners acquired J. Crew in a $3.1 billion leveraged buyout.17 As part of that buyout, J. Crew took on $1.6 billion in new debt.18 J. Crew also funded a dividend recap in 2013 by issuing $500 million in new payment-in-kind (PIK) notes.19 By 2016, the company saw distress and default in the near horizon if it could not refinance the PIK notes, given that the principal amount on the notes would continue to increase as each interest payment was paid with more debt.20

A. The “Trapdoor”

In consultation with its investment-banking and legal advisors, J. Crew settled on an aggressive strategy. It argued that its term-loan documents permitted it to move $250 million in trademark collateral to a new subsidiary for the benefit of refinancing the PIK notes.21 The key language would be found in Section 7.02(t) of the Term Loan Agreement, which became known as the “trap door.”22 It specifically permitted “Investments made by any Restricted Subsidiary that is not a Loan Party to the extent such Investments are financed with the proceeds received by such Restricted Subsidiary from an Investment in such Restricted Subsidiary made pursuant to Sections 7.02(c)(iv), (i)(B) or (n).”23

J. Crew likely negotiated for this carve-out to serve a limited purpose: to enable the company to invest in overseas businesses while shielding them from U.S. taxation. Prior to a 2017 tax-law change, a guarantee or a pledge of foreign subsidiaries or their assets would be deemed a taxable dividend.24 Hence, many U.S. businesses with foreign operations designate foreign subsidiaries as “restricted,” instead of making them loan parties.25 The restricted-subsidiary status protects lenders by allowing those subsidiaries to remain subject to the covenants in the loan documents, while the non-loan-party status prevents triggering the adverse tax consequences.26

J. Crew adopted a very different, general-purpose interpretation to Section 7.02(t).27 Under its interpretation, a non-loan-party restricted subsidiary could invest any asset type in any amount, provided that the agreement permitted inbound investment into a subsidiary of that kind. J. Crew found $250 million in permitted inbound-investment capacity from two other provisions in the agreement.28 It then hired a third-party firm to value its trademark collateral, which arrived at a value of $347 million.29 This allowed for an investment of 72% of the trademark collateral into a restricted, non-loan-party Cayman Islands subsidiary.30 From there, employing Section 7.02(t), J. Crew transferred (“invested”) the trademarks into a newly formed unrestricted subsidiary, freeing them from both the covenants and the debt obligations.31

B. The Agent and the Debt Exchange

Public discussion about J. Crew centered on the trapdoor provision. But there were additional vulnerabilities in the term lenders’ documents. First, J. Crew took advantage of the weakness in the relationship between the term lenders and their agent. It was able to convince the lenders’ original administrative and collateral agent, Bank of America, to release the liens on the trademark collateral to facilitate the transfer as it proposed.32 A group of term lenders subsequently coalesced and replaced the agent, but the first-mover advantage was significant. After all, it would have been harder for the lenders to unwind a transfer to which their agent had already consented. Next, J. Crew filed suit in a New York court seeking a declaratory judgment that the term loan documents permitted the maneuver.33

J. Crew then set about creating an offer to the term lenders.34 If it could get a majority of the lenders to agree, it could have the loan amended to drop the litigation and move the remaining 28% of the trademark value.35 To do so, the company created an exchange offer on a short timeline that subjected the individual term lenders to a prisoner’s dilemma.36 The terms included partial repayment of the loan at par. J. Crew also agreed to tighten its covenants going forward: it would delete the trapdoor loophole and include provisions that would prevent it from similarly transferring away its Madewell business in the future.37 The term lenders may have considered this offer unattractive. But if a majority consented, then those who refused to participate would be stuck with no repayment and no litigation right. This was a classic coercive exchange: to any holder who is unlikely to be a pivotal voter, participating is the better choice, no matter what the other holders do. When the dust settled, over 88% of the lenders supported the amendments.38 The refinancing bought J. Crew a longer runway, which finally ran out due to the impact of COVID-19 in May 2020, when the company filed for Chapter 11.39

C. Lessons from J. Crew

The J. Crew case illustrates the weaknesses of an omniscient actor or optimal contracting framework for understanding restructuring dynamics. Contractual loopholes do not exist in this framework because the parties are aware of all possible future interpretations at the time of contracting. Reconciling the J. Crew narrative within the omniscient-actor or optimal-contracting framework would force an awkward attempt to rationalize the term lenders’ contract as optimal. After all, an omniscient drafter would have contemplated J. Crew’s move, and a simple change to the language could have blocked the specific moves it made.40 The omniscient-actor or optimal-contracting framework would thus conclude that the lenders intended to permit J. Crew’s actions through the roundabout path it employed.

However, it is much more plausible that the parties who drafted the agreement never contemplated J. Crew’s interpretation of the trapdoor carve-out. Though market participants were broadly aware of the potential risks of unrestricted subsidiaries,41 J. Crew’s interpretation of the contract was particularly creative. Moreover, boldly antilender maneuvers like J. Crew’s were atypical at the time the loan was made.42 This may explain why other potential safeguards, such as the administrative agent’s role as a lender representative, proved so ineffective in preventing the collateral stripping.43

The aftermath of the J. Crew bankruptcy is also instructive. An optimal-contracting theory would predict that an inefficient loophole would certainly close after J. Crew, through renegotiation of existing loans or through modifications in new loans. In reality, agreements have evolved more slowly and heterogeneously to the unrestricted subsidiary threat.44 A variety of “J. Crew blocker” terms emerged in response, but covenant analysts argued that most of them are only partially effective at preventing unrestricted subsidiary transfers.45 Many other contracts continued to leave them out entirely.46 Other high-profile transfers in companies like Neiman Marcus, Cirque du Soleil, and PetSmart followed, each with its own unique workarounds of contractual constraints.47 Meanwhile, with aggressive tactics now the norm, borrowers moved on to exploit different contractual weaknesses.48 In Serta Simmons, Boardriders, and TriMark, borrowers employed “uptier exchanges,” whereby a majority of loan holders use required lender provisions to amend loan agreements and take a priority position over the minority.49

The J. Crew case study suggests a need for a model of debt contracting that accommodates imperfect and evolving contracts. These developments also have implications for bankruptcy law. J. Crew’s reorganization quickly proceeded to a plan that was fast and largely consensual. A skeptic might say that these changes are zero-sum value transfers that have no real efficiency implications. Our next case study illustrates otherwise.

II. nine west

Contracting optimally about bankruptcy requires complete foresight about the many ways that contracts interact. Nine West’s bankruptcy illustrates that in a complex capital structure, seemingly minor choices can have large unanticipated consequences. When Nine West filed for bankruptcy, its corporate structure was the product of the $2.2 billion leveraged buyout of The Jones Group by Sycamore Partners and KKR in 2014.50 As part of the transaction, the Stuart Weitzman, Kurt Geiger, and Jones Apparel Group brands were carved out from the company debt free and sold to Sycamore affiliates for $641 million in cash.51 The remaining brands formed a new entity named Nine West, which retained $700 million of existing debt, and issued $800 million of new debt.52 The organizational structure of Nine West consisted of many subsidiary corporations under the ownership of a parent corporation, NWHI.53

The most important

intercreditor conflict in the Nine West case took place between two classes of

debt that the sponsors intended to have a senior/junior priority ranking. The

relevant junior class consisted of Unsecured Notes that were obligations of

only NWHI. One of the securities in this class were the 2034 Notes, issued a

decade before the leveraged buyout (LBO).54 Because the 2034 Notes

contained standard investment-grade covenants,55 they had little protection

against dilution by the

LBO.56

This gave the sponsors the incentive to keep the 2034 Notes in place, to sell The

Jones Group companies free and clear of these claims, and to make any new LBO

debt senior to it.

The relevant senior class was an Unsecured Term Loan (UTL) issued between the signing and the closing of the LBO. After successfully drumming up interest for a secured-term facility, Morgan Stanley approached Sycamore about raising incremental debt and reducing their equity commitment.57The new facility was set up as an unsecured loan. Its seniority to the Unsecured Notes would come via guarantees by NWHI’s operating subsidiaries.58 Given the compressed timeline, it was likely quicker and easier to structure the UTL this way rather than securing the debt with collateral: this obviated the need to negotiate an intercreditor agreement between the UTL and the existing secured lenders. This seemingly inconsequential choice regarding Nine West’s post-LBO capital structure would set the stage for many of the entitlement issues that arose during the bankruptcy proceedings.

Saddled with debt and deprived of the revenue streams from the carved-out businesses, Nine West faltered as it faced unfavorable macroeconomic conditions that negatively impacted the company and the retail industry at large. With most of its obligations coming due in 2019, the company sought to develop a restructuring plan.59 After out-of-court negotiations failed to reach a consensus, Nine West ultimately filed for bankruptcy in April 2018.

A. The LBO Litigation and the “Belk Letter”

The bankruptcy proceedings were contentious from the very beginning. At the first hearing of the case, one of the lawyers noted, “[T]here is a lot to talk about. It’s not simple who decides . . . to go after whom.”60 The key conflict was not about what to do with Nine West’s assets.61 Instead, the costly conflict revolved around the uncertain entitlements to Nine West’s value across the creditor groups. The unsecured Noteholders, including the hedge fund Aurelius, were the major parties whose interests were advanced by these disputes. Without them, the purported waterfall would pay the secured lenders in full and leave the UTL with the remaining enterprise value. Hence, it was the Noteholders, with the backing of the Unsecured Creditors Committee, who advanced the entitlement issues.62

The LBO deal played a crucial role in generating this entitlement uncertainty, in two ways. First, the asset sales to Sycamore-owned entities and the new LBO debt gave rise to possible fraudulent-transfer and breach-of-fiduciary-duty claims. These claims alleged that in addition to burdening Nine West with excessive amounts of debt, Sycamore manipulated the projections of the various Jones Group units to acquire the carved-out assets at a discount to their true value. These claims, if pursued, could seek recovery from Sycamore and avoidance of both the lost asset value and the new debt incurred in the LBO.

In the settlement negotiations, the debtor’s representatives sought a resolution that would settle the LBO litigation and provide a release to Sycamore. But the UTL group, unconcerned with Sycamore’s release, decided to join forces with the Noteholders instead. They reached an intercreditor settlement on a plan proposal that would give 92.5% of the reorganized Nine West’s equity to the UTL holders.63 The Noteholders would receive some of the remaining equity and a litigation trust to pursue the claims against Sycamore and other parties.

Immediately after it became clear that Sycamore would not receive a release, it played a valuable trump card. Belk, one of Nine West’s main customers and a Sycamore portfolio company,64 sent a letter to Nine West providing notice that it would be terminating their business relationship.65 Since Belk generated over $100 million per year of Nine West’s sales,66 this posed a major threat to Nine West’s future business and the UTL’s potential equity value.

Sycamore’s gambit worked. Following the Belk letter, the UTL holders wanted Sycamore’s participation in the plan process because their future equity value depended on the return of Belk’s business. The UTL holders broke from the intercreditor settlement and objected to the Unsecured Creditor Committee’s standing to pursue claims. This upended settlement negotiations and sent the parties back to the drawing board.67 The bankruptcy judge ordered the parties to mediation, with the hope of reaching a new settlement.68

B. Parent/Subsidiary Entitlement Dispute

A second major cause of entitlement disputes was the decision to make the UTL senior through subsidiary-entity guarantees, rather than through security. In simplified terms, it gave rise to the questions: which entities in the corporate group actually own the assets, and which are actually responsible for the debts? Though the Noteholders raised more issues than these, three issues are particularly illustrative of the complex interactions that can flow from a relatively minor decision.69

First, during Nine West’s regular course of business, the operating subsidiaries of NWHI would generate cash and contribute it up to NWHI, with a corresponding intercompany claim recorded in a company ledger. At the time of bankruptcy, the operating subsidiaries asserted $700 million of intercompany claims against NWHI.70 The Noteholders argued that these obligations lacked the characteristics of true claims. They argued that the contributions from the subsidiaries to NWHI should be recharacterized as dividends, not loans. The cash thus properly belonged to NWHI.71

Second,the Noteholders questioned the ownership of intellectual property that Nine West sold in the early stages of the case. Though the title to the IP was formally held by the NWD subsidiary, the Noteholders argued that much of the value of that IP derived from the sales, marketing, and growth efforts conducted by NWHI. Following precedent from a similarly contentious interdebtor IP ownership dispute in the Nortel bankruptcy case, they argued that the proceeds of the asset sale belonged partially to NWHI.72

Third, as part of the proposed settlement involving Sycamore, Belk would agree to continue its business relationship with Nine West. The Noteholders argued that the value of the returned Belk business belonged in greater amount to NWHI than the 7% equity share it stood to receive in the reorganization plan.73 In effect, the return of the Belk business would settle claims that management breached their fiduciary duty to NWHI by terminating the Belk relationship. Hence, the proceeds of the settlement belonged to NWHI.74

These disputes were not only factually and legally complex on their own, but also interacted with each other and the LBO litigation claims.75 Financial advisors created valuation models that included toggle switches for each of the claims to forecast how the value would flow based on all possible resolutions of the disputed entitlements.76

C. The Final Settlement

The mediation

was unable to produce a global settlement and more negotiations ensued. Finally,

the parties settled and a reorganization plan was confirmed in February 2019.77Key to reaching an agreement was the debtor’s

decision to divide and conquer the Unsecured Creditors’ Committee.78 They created a “Cash-Out Option” for

the trade creditors of Nine West that enhanced their recovery relative to the

Noteholders.79 Since the trade creditors

held three votes on the seven-member Committee, their support, along with that

of the UTL lenders, drove the Committee’s approval of the plan.80 Still, not all parties were

satisfied with the settlement or how it was attained. The 2034 Noteholders

viewed the settlement with Sycamore as “paltry” and called the Cash-Out Option

a “buy off” or “bribe” of the trade creditors.81 Despite the Noteholders’ dissatisfaction, the plan moved

forward with Sycamore agreeing to contribute $120 million to the bankruptcy

estate to settle litigation claims82 and Belk committing to a three-year sales contract with

Nine West.83

The competing claims to Nine West’s assets took a considerable amount of time and effort to resolve. Ultimately, the Nine West case generated over $140 million in professional fees and other expenses.84 While other Chapter 11 cases have been costlier in raw dollars, the $142.8 million in professional fees estimated in the plan was 23% of the $600 million enterprise-value estimate.85 At the final hearing, the lawyers recognized the “extreme expense” of the case, cautioning, “[M]aybe it’s an object lesson both to the professionals, but really to the various creditor constituents, that maybe there’s a better way than fighting over every issue, litigating every issue.”86

D. Lessons from Nine West

The transactions that comprised Nine West’s 2014 LBO were not optimal, at least not from the perspective of minimizing bankruptcy costs.87 Indeed, they set the stage for a costly and contentious bankruptcy case that cost the creditors substantially, as exorbitant professional fees ate into their recoveries.88 Yet, major costs of the case can be tied to some relatively minor capital-structure decisions. The lack of protective covenants in the 2034 Notes subsidized the LBO, creating an incentive for Sycamore to dilute these Notes by spinning off assets and incurring new senior debt. The decision to swap in the UTL for equity late in the process, due to unexpectedly favorable debt-market conditions, also proved costly. In particular, the choice to give priority to the UTL through subsidiary guarantees gave rise to the interdebtor ownership questions that complicated the negotiations. If the UTL had been secured by specific assets, many of these legal-entity ownership disputes would not have arisen. Nine West could have given the UTL creditors a second lien on the collateral that backed the secured-term lender claims, for example. This would have achieved a comparable priority position for this debt between the secured-term creditors and the Noteholders.

One can hardly blame Sycamore and its professionals if they did not foresee every dispute their capital structure choices would create four years later in bankruptcy court. In this way, the Nine West case illustrates the extreme nature of the omniscient-actor model in assuming parties can contract optimally about bankruptcy.

A second lesson from Nine West is that entitlement disputes and the litigation expenses they create can be a more important efficiency driver than the typical reorganization-versus-liquidation conflict emphasized in the literature.89 In this regard, it suggests the need for a better understanding of the connection between capital structures, entitlement conflicts, and bankruptcy costs. It also suggests the need for better theory and evidence on the bankruptcy bargaining process. In theory, parties with symmetric information about an entitlement dispute should strike a Coasean bargain, settling their disputes and saving themselves unnecessary litigation costs.90 In entitlement dispute cases like Nine West and Nortel, those predictions failed badly.

Future research is needed to uncover the reasons why some cases reach quick and relatively inexpensive bargains, while other cases go the way of Nine West. Law-and-economics models typically assume that only the parties’ positions in the capital structure in the case at hand are relevant.91 In reality, the identity of the claimholders, their attorneys, and their past and future interactions can be important drivers of bargaining outcomes. The role of judges and mediators in steering parties toward settlement is also worthy of future study.

III. the law and economics of bankruptcy revisited

Models are useful tools when properly applied. We often need models to simplify the world in order to gain intuition and clarity about a particular aspect of it. The optimal-contracting framework has made important contributions to the bankruptcy and corporate-finance literatures. In particular, it highlights that ex-ante considerations behind capital structure and contracting choices are an important part of the efficiency calculus. The framework is also useful for identifying important economic forces that can generate testable predictions. The priority of secured credit, for example, can be justified based on efficiency concerns related to asset substitution92 or debt overhang.93 Empirical evidence confirms the presence of these problems.94 A law that focuses only on ex-post concerns at the expense of respecting these priorities would be suboptimal. Debt overhang and option-value frameworks are useful conceptual tools for explaining incentive problems inside bankruptcy and proposals to address them.95

But an omniscient-actor model also has important flaws. It misses significant aspects of the narratives in complex restructurings like those of J. Crew and Nine West, such as loopholes and unanticipated interactions between contracts. It also falls short as a convincing justification for a freedom-of-contract approach to bankruptcy-law design.

The existing normative corporate-bankruptcy literature follows several approaches. The contractarian branch of this literature questions bankruptcy law from first principles.96 It takes the omniscient-actor or sophisticated-party framework seriously as a means of analyzing contracts and capital structures, and the optimal bankruptcy law that responds to these choices. The main consensus of this literature is that mandatory provisions of the Bankruptcy Code are inefficient, and expanding contractual freedom would enhance efficiency.97 This conclusion follows very closely from the unbounded cognitive abilities of the contracting parties: any potentially useful feature of the Bankruptcy Code would be anticipated and could be replicated by contract if the parties actually wanted it. On the other hand, a mandatory restriction might block a better alternative that could have ex-ante or ex-post efficiency benefits.

The contractarian literature properly insists upon a principled foundation for the law and challenges the status quo. But the optimal laws it imagines are radically different from the bankruptcy laws we observe in the real world. Moreover, the omniscient-actor assumptions on which the arguments rest are (justifiably) unpersuasive outside the world of law-and-economics academics. As such, it places the analysis too distant from any real-world controversy to have practical impact.

The alternative normative approach takes some empirically observed aspects of contracts and capital structure as given and analyzes the law from this starting point. This is the approach taken by Thomas Jackson in the original Creditors Bargain framework, by assuming the presence of uncoordinated unsecured creditors to justify the automatic stay.98 Some important work draws lessons inductively from case examples and trends, as we do here.99 Other work puts important weight on contractual incompleteness,100 such as the inability of creditors to police the contracts of other creditors.101 These approaches are more willing to acknowledge that bankruptcy law can play a constructive role in financial distress.

Nevertheless, without acknowledging boundedly rational contracting parties, they can never be fully responsive to contractarian critiques of mandatory features. Even if omniscient actors cannot describe all contingencies to a court, they are fully aware of the problem and the optimal response to it. Armed with this assumption, the theorist can always devise a choice-enabling regime that is superior to existing law. Our case studies lead us to believe, however, that a large policy change to a freedom-of-contract regime would set off a complex and unpredictable adjustment process—not an immediate move to a superior equilibrium.

IV. bankruptcy in a complex world

Insights from the study of complex systems can inform a theory of bankruptcy that emphasizes multiple creditor problems at its core. Nobel laureate Herbert A. Simon defined complex systems as systems “made up of a large number of parts which interact in a nonsimple way.”102 A key insight in complex systems analysis is emergence:the whole behaves differently from the sum of its parts because the parts interact in nontrivial ways.103 Complex-systems analysis thus cautions against making inferences based on a reductionist approach that considers only the properties of the parts.104

Bankruptcy is a complex system that law-and-economics scholarship analyzes in a reductionist way. In particular, the literature assumes that the cognitive problem of designing a capital structure involving the interaction of a multiplicity of contracts and parties is no harder than the problem of designing one contract involving only two parties. Many interactions between contracts are straightforward, and reliable and predictable tools have evolved to address them. The use of security interests to prioritize one creditor over another is an obvious example. However, other interactions between rights become apparent only at the time of the conflict. These are unlikely to be resolved optimally through prebankruptcy ordering alone. We suspect this is true particularly when they involve contract terms that benefit the parties to the contract at the expense of nonparties, and contract types that are in earlier stages of their evolution.105

Our case studies also suggest the importance of a law’s robustness.106An effective bankruptcy law must be able to handle not only the interaction of the optimal contracts and Coasean bargaining parties in our models,107 but also the interaction of the suboptimal contracts and intransigent bargaining parties the law sometimes encounters in practice.108 In the RadioShack bankruptcy, for example, an interlocking web of intercreditor agreements led to mutually inconsistent control rights over one party’s right to credit bid.109 The bankruptcy judge seemed to take a practical and efficiency-oriented approach to this conflict, channeling the parties toward a sale outcome that maximized value for the parties as a whole, rather than attempting to reconcile an uncontemplated conflict between contracts.110 Institutional features like the automatic stay and judicial discretion clearly play an important robustness role in preventing big mistakes.

An alternative theoretical approach would take a more realistic view about the way contracts evolve. Scholarly literature on the role of lawyers in the contract-production process emphasizes the path dependence of contracts.111 Lawyers start with drafts from prior deals and adjust terms incrementally. They rely heavily on what has worked in the past.112 Innovation of new terms is relatively rare, and wholesale restructuring of form contracts is rarer still.113 A theoretical approach that simulates evolution and the interaction of evolving contracts and takes account of these frictions can be a fruitful approach for future research.114 From a normative perspective, a more realistic theory of contract evolution can generate principles about when freedom-of-contract logic should prevail, and when mandatory provisions are justifiable. We cannot settle these issues here, but they cannot be resolved using only deductive reasoning from an omniscient-actor framework.

A complexity perspective can also make way for an empirical agenda that seeks to understand debt‑contract evolution and, importantly for bankruptcy purposes, coevolution. The optimal-contracting framework implies that contracts respond immediately to changes in economic conditions.115 Existing empirical literature suggests, however, that debt contracts evolve gradually. Syndicated loan agreements have undergone a twenty-year secular trend toward “covenant-lite” features.116 Some important terms in DIP loans do not seem to respond quickly to changes in economic conditions over the business cycle,117 but these loans have changed substantially over a long horizon, from a standard corporate loan to a highly tailored instrument of governance over the bankruptcy case.118 We still know little, however, about what forces drive this evolution and its speed. We know even less about coevolution of different contract classes. Do terms in bond indentures respond to changes in secured term loans, DIP loans, or intercreditor agreements that affect bond investors? What causes the migration of terms from bond indentures to loan agreements, and what are the consequences of this migration? Future research can provide answers to these important questions.

Conclusion

The law-and-economics literature on bankruptcy often assumes that the product of financial contracts involving sophisticated commercial actors creates a globally optimal capital structure. This model leaves no role for bankruptcy law, other than a costly interference with contractual freedom. The J. Crew and Nine West case studies cast doubt on this presumption. The primary deficiency in the law-and-economics account is the omniscient-rational-actor assumption, whereby parties are aware of all future contingencies and the effect of all possible contractual terms. The assumption’s lack of realism is magnified in the financial-distress setting because the interaction of numerous contracts and rights creates a significantly more complex governance problem than a single contract between two parties. In addition, distress conditions amplify the incentive of sophisticated parties to search for loopholes and exploit flaws. A theory involving bounded rationality can thus be harmonious with the benefits of a bankruptcy law that is limited to solving multiple-creditor problems. We also propose avenues for future research in the law and economics of bankruptcy that scholars can unlock by recognizing that even the most sophisticated parties are imperfect.

Kenneth Ayotte, Robert L. Bridges Professor of Law, University of California, Berkeley School of Law. Christina Scully, J.D. 2021, University of California, Berkeley School of Law. This paper benefited from many helpful discussions with professionals in debt finance and restructuring. We thank Daniel Golden, Samantha Good, David Kurtz, Christopher Marcus, David Nemecek, Robert Stark, Philip Tendler, and Michael Weitz for background information connected to these cases. Thanks also to Barry Adler, Adam Badawi, Vince Buccola, Tony Casey, Jared Ellias, Claire Hill, Michael Ohlrogge, Bob Rasmussen, Kate Waldock, and Spencer Williams for helpful comments and conversations.

See Declaration of Ralph Schipani, Interim Chief Executive Officer of Nine West Holdings, Inc., in Support of Debtors’ Chapter 11 Petitions and First Day Motions at 19, 46, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. Apr. 6, 2018), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X1Q6NVKIH782/download [https://perma.cc/R2Q2-X98U].

We follow Herbert Simon in using the term “omniscient” to critique the assumptions used in the literature on financial contracting. We do this to emphasize, as Simon did, the difficulties of thinking ahead to all possible contingencies and evaluating all possible contracting responses to arrive at an optimal contract. See Herbert A. Simon, Nobel Memorial Lecture on Rational Decision-Making in Business Organizations (Dec. 8, 1978), https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/simon-lecture.pdf [https://perma.cc/7E3U-85NF].

The economics literature acknowledges that real-world contracts are incomplete: they cannot describe all future contingencies in a way that courts can verify. The influential property-rights theories of the firm assume, however, that parties are omnisciently rational. That is, they are aware of all contingencies and respond optimally given these constraints. See, e.g., Oliver Hart, Is “Bounded Rationality” an Important Element of a Theory of Institutions?, 146 J. Inst. & Theoretical Econ. 696, 696 (1990). The economics literature formalizing bounded rationality is still in its early stages. See Jean Tirole, Cognition and Incomplete Contracts, 99 Am. Econ. Rev. 265, 265 (2009); Patrick Bolton & Antoine Faure-Grimaud, Satisficing Contracts, 77 Rev. Econ. Stud. 937, 938 (2010).

One of us has taken this approach in prior work. See Kenneth Ayotte & Stav Gaon, Asset-Backed Securities: Costs and Benefits of “Bankruptcy Remoteness,” 24 Rev. Fin. Stud. 1299, 1301 (2011)In the corporate-finance literature, this approach is common. See, e.g., Nicola Gennaioli & Stefano Rossi, Contractual Resolutions of Financial Distress, 26 Rev. Fin. Stud. 602 (2013).

There is a large literature questioning the contractarian approach to bankruptcy. See, e.g., Charles J. Tabb, Of Contractarians and Bankruptcy Reform: A Skeptical View, 12 Am. Bankr. Inst. L. Rev. 259, 260 (2004) (“I am skeptical about the utility of freedom of contract in the bankruptcy arena.”); Melissa B. Jacoby, Corporate Bankruptcy Hybridity, 166 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1715, 1716 n.3 (2018) (citing “analysis and critiques” of contractualism); Anthony J. Casey, Chapter 11’s Renegotiation Framework and the Purpose of Corporate Bankruptcy, 120 Colum. L. Rev. 1709, 1712 (2020) (“But the real problem for any bankruptcy contract—or legislation—is not in convening the bargainers. It is in dealing ex post with the incomplete terms those parties actually drafted.”).

Contractarian scholars note that a contractual solution under the current legal framework may be imperfect due to legal restrictions on the contracting space. They also recognize a role for law in addressing involuntary creditors. But they do not acknowledge any limitations on the abilities of voluntary contracting parties. See Barry E. Adler & Marcel Kahan, The Technology of Creditor Protection, 161 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1773, 1791-94 (2013).

Barry E. Adler expresses this point of view most directly. Barry E. Adler, The Creditors’ Bargain Revisited, 166 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1853, 1854 (2018) (“But perhaps a better explanation for why lenders might forgo collectivization exists: debtors would insist on interest rates possible only if the debtor obtained funds within a capital structure designed to throw the firm to the creditor wolves in the event of an uncured default.”).

Continuous-time finance models often make this assumption. See, e.g., Hayne E. Leland & Klaus Bjerre Toft, Optimal Capital Structure, Endogenous Bankruptcy, and the Term Structure of Credit Spreads, 51 J. Fin. 987, 1014 (1996); see also Gary Gorton & Nicholas S. Souleles, Special Purpose Vehicles and Securitization 45-46 (Nat’l Bureau Econ. Rsch., Working Paper, Paper No. 11190, 2005), https://ssrn.com/abstract=684716 [https://perma.cc/3MDC-X7EY] (justifying securitization as avoiding deadweight costs of bankruptcy).

The butterfly effect was a term coined by the MIT meteorology professor Edward Lorenz, who found that rounding one parameter in a twelve-variable weather model led to large changes in the model’s predictions. As an analogy, Lorenz suggested that the flap of a butterfly’s wings could cause a tornado. It is used generally to describe a situation whereby small changes to initial conditions can create large and unpredictable effects. See Peter Dizikes, When the Butterfly Effect Took Flight, MIT Tech. Rev. (Feb. 22, 2011), https://www.technologyreview.com/2011/02/22/196987/when-the-butterfly-effect-took-flight [https://perma.cc/KLQ4-SWCC].

See Complaint at 18, Eaton Vance Mgmt. v. Wilmington Sav. Fund Soc’y, No. 654397/2017 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2017), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X1Q6NSHTE2O2/download?documentName=E1.pdf&fmt=pdf [https://perma.cc/E7PS-7DNY].

See id. at 21. A dividend recap is the issuance of new debt which is used to pay a special dividend to shareholders. As a result, a dividend recap reduces the company’s equity financing in relation to its debt financing. Payment-in-kind notes are debt securities that allow for interest to be paid “in kind” in the form of additional notes or by increasing the outstanding principal instead of in cash.

See id. at 35-36; Christine Dreyer McCay, George Ticknor & Jonathan Young, J. Crew Group, Inc.: Use of Credit Facility Baskets Eviscerates Value of Term Loan Collateral, JDSupra (Oct. 5, 2017), https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/j-crew-group-inc-use-of-credit-facility-48821 [https://perma.cc/MVJ9-XER2].

See J. Crew Grp., Inc., Amendment No. 1 to Amended and Restated Credit Agreement (July 13, 2017), https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/0001051251/000156459017013589/jcg-ex101_11.htm [https://perma.cc/A48M-W93S].

See Scott Lilienthal & Deborah Staudinger, Tax Relief for U.S. Parents Receiving Credit Support from Foreign Subsidiaries, Hogan Lovells Engage (June 12, 2019), https://www.engage.hoganlovells.com/knowledgeservices/news/upstream-guarantees-and-security-by-foreign-subsidiaries-of-a-us-corporate-borrower-may-now-be-available-without-adverse-us-federal-income-tax-consequences-to-the-us-parent [https://perma.cc/6P4Z-Q8N6].

See generally David W. Morse, Where Did My Collateral Go?, Secured Lender (July 15, 2017), https://www.martindale.com/matter/asr-2500841.Otterbourg_TSL.pdf [https://perma.cc/95EZ-X5EY] (describing J. Crew’s strategy to take advantage of the trapdoor provision).

The agent may have allowed the release due to a concern about losing future syndication business if they pushed back on a sponsor-owned borrower. See Joel H. Levitin & Richard A. Stieglitz, Jr., Free Agency in Restructuring? Best Practices for Administrative Agents of Distressed Loans, Am. Bankr. Inst. J. 2 (Apr. 1, 2020), https://www.cahill.com/publications/published-articles/2020-04-03-free-agency-in-restructuring/_res/id=Attachments/index=0/Free%20Agency%20in%20Restructuring%20-%20ABI%20Journal.pdf [https://perma.cc/MM3N-MJB9]. Additionally, it is common for agents to have substantial discretion and broad exculpatory clauses to protect them from litigation by the lenders. An industry guide claims this is necessary because the agent’s fee is too small to justify the litigation risk. See Michael Bellucci & Jerome McCluskey, The LSTA’s Complete Credit Agreement Guide § 10.1.4 (2d ed. 2016).

See Tiffany Kary, J. Crew Lenders File New Lawsuit over Trademark Transfer, Bloomberg Quint (June 22, 2017, 8:25 PM), https://www.bloombergquint.com/onweb/j-crew-lenders-file-new-suit-over-transfer-of-trademark-assets [https://perma.cc/L743-R82U].

See Vanessa Friedman, Sapna Maheshwari & Michael J. de la Merced, J. Crew Files for Bankruptcy in Virus’s First Big Retail Casualty, N.Y. Times (May 3, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/03/business/j-crew-bankruptcy-coronavirus.html [https://perma.cc/H5K8-MTLL].

J. Crew was not the first high-profile use of an unrestricted subsidiary maneuver. In iHeartMedia, a similar tactic was employed in 2016. See Brad Cheek, Tearin’ up iHeart: The Recent Trend with Troubled Companies and the Unrestricted Subsidiary Transfer Tactic, 23 N.C. Banking Inst. 271 (2019); Franklin Advisers, Inc. v. iHeart Commc’ns Inc., No. 04-16-00532-CV, 2017 WL 4518297 (Tex. App. Oct. 11, 2017).

It is telling in this regard that J. Crew has been used as a slang verb for harming lenders. See Joe Rennison, Asset Transfers Leave Creditors Feeling ‘J Screwed,’ Fin. Times (June 5, 2020), https://www.ft.com/content/efda1248-4091-4363-9936-1601c4639b72 [https://perma.cc/YS9C-6CGD].

In the PetSmart unrestricted-subsidiary maneuver, the administrative and collateral agent refused to consent to the collateral release, giving rise to litigation. See Fred Cristman, Nathan Cooper, James Adams & Hali Katz, “The Chewy Phantom Guarantee”: A Cautionary Tale of Today’s Leverage Finance Market, Hogan Lovells Engage (Sept. 30, 2019), https://www.engage.hoganlovells.com/knowledgeservices/news/chewing-through-baskets-the-chewy-phantom-guarantee-and-a-cautionary-tale-of-the-release-of-a-valuable-guarantee-and-collateral-package_1 [https://perma.cc/9WGK-T5SA]. Uptier exchanges, mentioned in notes 48-49 and accompanying text, infra, circumvent this problem, because they gain consent from a majority of the lenders.

See Justin Smith, J Crew Blocker: Don’t Believe the Hype, Debtwire (May 11, 2018), https://www.debtwire.com/info/j-crew-blocker-don%E2%80%99t-believe-hype [https://perma.cc/QLU6-AEBR].

See Shana A. Elberg, Evan A. Hill & Catrina A. Shea, Uptier Exchange Transactions Remain in Vogue, Notwithstanding Litigation Risk, Skadden (Feb. 2, 2021), https://www.skadden.com/insights/publications/2021/02/uptier-exchange-transactions [https://perma.cc/9VCD-R7KA].

Id.; N. Star Debt Holdings, L.P. v. Serta Simmons Bedding, LLC, No. 652243/2020 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. June 11, 2020); LCM XXII LTD. v. Serta Simmons Bedding, LLC, No. 20-cv-5090 (S.D.N.Y. July 2, 2020); ICG Global Fund 1 DAC v. Boardriders, Inc., No. 655175/2020 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Oct. 9, 2020); Audax Credit Opportunities Offshore Ltd. v. TMK Hawk Parent, Corp., 72 Misc. 3d 1218(A) (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Aug. 16, 2021) (No. 565123/2020).

See Declaration of Ralph Schipani, supra note 1, at 8; Notice of Filing of the Debtors’ Disclosure Statement for the Debtors’ First Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code at 25, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. Oct. 17, 2018), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X3SD5VSFRHP9NBRRBVKNLKJJN66/download [https://perma.cc/3ZYY-GUZC].

See Notice of Motion of the 2034 Notes Trustee for Entry of an Order Granting Leave, Standing, and Authority to Commence and Prosecute a Certain Claim on Behalf of the NWHI Estate at 4-12, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Jan. 31, 2019), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X696I51H4B78H191VHGRIB05OS7/download [https://perma.cc/H69A-SQGX].

When issued, the 2034 Notes were rated Baa2 by Moody’s, two notches above speculative grade. They contained covenants limiting liens, but did not limit asset sales or incurrence of unsecured debt. This is common in investment-grade bonds. See David Azarkh & Sean Dougherty, High Yield vs. Investment Grade Covenants Chart, LexisNexis (2019), https://www.stblaw.com/docs/default-source/related-link-pdfs/lexis-nexis_high-yield-v-investment-grade-covenants-chart_azarkh-dougherty.pdf [https://perma.cc/R5DG-CAMV].

Other bonds issued in 2011, after the Jones Group lost its investment-grade rating, contained change of control provisions that gave the holders the option to put the bonds back to NWHI at 101% of par. As a result, a majority of these bondholders exchanged their notes for new notes with a higher interest rate reflecting the post-leveraged-buyout risk. See Declaration of Ralph Schipani, supra note 1, at 22-23.

See Sycamore’s Memorandum of Law in Support of Equity Holders Settlement at 13, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. Dec. 10, 2018), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X2NSOU4QVVQ967Q5UIBQL3P5RE7/download [https://perma.cc/5C6U-M246].

See Hearing Transcript at 52, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (May 8, 2018), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X1Q6NVKIH782/download?documentName=114.pdf&fmt=pdf [https://perma.cc/Y6JF-WMB5].

Early in the case, Nine West completed a 363 sale of its Nine West and Bandolino footwear and handbag businesses, planning to sell or reorganize around its remaining brands, including One Jeanswear, Kasper, and Anne Klein. Fashion Company Nine West Emerges from Bankruptcy as “Premier Brands,” Reuters (Mar. 20, 2019), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ninewest-bankruptcy/fashion-company-nine-west-emerges-from-bankruptcy-as-premier-brands-idUSKCN1R127X [https://perma.cc/9UYJ-B6XM].

See Declaration of Daniel H. Golden in Support of the Motion of the Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors for Entry of an Order Granting Leave, Standing, and Authority to Commence and Prosecute Certain Claims on Behalf of the NWHI Estate and Exclusive Settlement Authority in Respect of Such Claims at 121-22, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Oct. 22, 2018) [hereinafter Declaration of Daniel H. Golden], https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X4DN11AL7HJ9D7PLNFS9P68GJQQ/download [https://perma.cc/N9T6-9NVK].

See Unsecured Term Loan Lenders’ Objection to Creditors’ Committee’s Standing Motion and Statement in Support of Confirmation of the Plan at 36, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Dec. 10, 2018), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X2PL65JK51R9MG8JAPEP9S7BSL9/download [https://perma.cc/AN7M-Z3VH].

See Debtors’ Clarifications to the Ad Hoc Group of Unsecured Noteholders’ Notice of Filing of Additional Cleansing Materials at 80, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Sept. 11, 2018), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X1Q6NVKIH782/download?documentName=677.pdf&fmt=pdf [https://perma.cc/L9TL-YJ3Y].

See Mediation Order, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Nov. 9, 2018), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X51GFKG5BRI8V8BTR91JKPDHU0D/download [https://perma.cc/VN23-DA79].

Another issue raised by the Noteholders was that the value of the Kasper Group, paid for by NWHI and held by an insolvent subsidiary, was a fraudulent transfer. See The 2019 Notes Trustee’s Objection to the Debtors’ Second Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization at 50-51, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Jan. 24, 2019), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X1R329A38UG9TPQ0SVURVTMD97C/download [https://perma.cc/9SNS-7WUZ].

See Debtors’ Omnibus Reply to Plan Confirmation Objections at 31, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Feb. 1, 2019), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X4UTDHFF6HS9BKRDQ4DKO0I77KU/download [https://perma.cc/A6VN-HNDE]; The 2019 Notes Trustee’s Objection to the Debtors’ Second Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization, supra note 69, at 42-43.

See Notice of Filing of the Debtors’ Disclosure Statement for the Debtors’ First Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code, supra note 50, at 45-46; Notes Trustee’s Objection to the Debtors’ Second Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization, supra note 69, at 40-42.

The UTL lenders countered with arguments of their own involving subrogation rights. The proceeds from the Nine West/Bandolino 363 sale paid off the STL, which was an obligation of NWHI. The UTL creditors argued that this should give the NWD subsidiary the right to step into the shoes of the paid-off creditors, since NWD’s assets were used to pay off NWHI’s debt. See Debtors’ Omnibus Reply to Plan Confirmation Objections, supra note 71, at 25-29.

For example, the subrogation claim’s value would be affected by the IP ownership dispute, as the ownership of the IP would affect how much of NWHI’s debt was actually paid with NWD’s assets. Similarly, if the fraudulent-transfer litigation resulted in avoidance of the STL and UTL debts, the subrogation right would become irrelevant.

See Order Confirming Debtors’ Third Amended Plan of Reorganization Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. Feb. 27, 2019), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X1Q6NVKIH782/download?documentName=1398.pdf&fmt=pdf [https://perma.cc/5KTG-SD88].

See 2034 Notes Trustee’s Objection to Confirmation of the Debtors’ Second Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization at 7, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Jan. 24, 2019), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X6K69O0DLUJ8UQPFNR30GRH69TB/download [https://perma.cc/QAH6-G538].

See Notice of Filing of Further Revised Debtors’ Third Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code at 16, In re Nine West Holdings, No. 18-10947 (Feb. 27, 2019), https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/blaw/document/X1Q6NVKIH782/download?documentName=1396.pdf&fmt=pdf [https://perma.cc/7QCZ-73ZB]. Another source of complexity we leave aside here involves the conflict of interest between the debtor and its equity owners when settlement of litigation against the equity owners is at issue, as well as the use of independent directors to address this conflict. This undoubtedly contributed to the acrimony and expense in the Nine West case. See Jared A. Ellias, Ehud Kamar & Kobi Kastiel, The Rise of Bankruptcy Directors (Eur. Corp. Governance Inst., Working Paper No. 593, 2021), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3866669 [https://perma.cc/3G86-PFEC].

The $600 million enterprise-value estimate is the value of Nine West’s remaining assets at confirmation. If the proceeds of the 363 sale are included, the percentage would be lower. See Unsecured Term Loan Lenders’ Objection to Creditors’ Committee’s Standing Motion and Statement in Support of Confirmation of the Plan, supra note 63, at 36.

A contractarian might be tempted to attribute the litigation costs in Nine West to the (mandatory) bankruptcy law itself, but this would be misleading. The interdebtor entitlement disputes would have been viable even in a nonbankruptcy liquidation of Nine West. However, the costs of the litigation connected to fraudulent transfer is vulnerable to a contractarian critique.

See Abraham L. Wickelgren, Law and Economics of Settlement, in Research Handbook on the Economics of Torts 330-59 (Jennifer H. Arlen ed., 2013). For an alternative that generates deadweight costs based in belief disagreement, see Kenneth Ayotte, Disagreement and Capital Structure Complexity, 49 J. Legal Stud. 1 (2020).

See, e.g., Barry E. Adler, Financial and Political Theories of American Corporate Bankruptcy, 45 Stan. L. Rev. 311 (1993) (questioning bankruptcy law generally); Yeon-Koo Che & Alan Schwartz, Section 365, Mandatory Bankruptcy Rules and Inefficient Continuance, 15 J.L. Econ. & Org. 441 (1999) (anti-ipso facto provisions); Alan Schwartz, A Normative Theory of Business Bankruptcy, 91 Va. L. Rev. 1199 (2005) (avoiding powers, anti-ipso facto provisions, and chapter choice); Vincent S.J. Buccola, Bankruptcy’s Cathedral: Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Distress, 114 Nw. U. L. Rev. 705 (2019) (the automatic stay). More recently, Professor Schwartz has recognized the benefits of mandatory bankruptcy based on externalities across firms. See Antonio E. Bernardo, Alan Schwartz & Ivo Welch, Contracting Externalities and Mandatory Menus in the US Corporate Bankruptcy Code, 32 J.L. Econ. & Org. 395 (2016).

Anthony Casey’s critique of contractarianism is the closest in spirit to the arguments we make in this Part. Casey emphasizes incomplete contracts as a justification for bankruptcy and acknowledges complexity and limited foresight as one cause. We take the additional step here of arguing that bounded rationality is a necessary condition for mandatory features. See Casey, supra note 6.

Our hypothesis is that it is particularly difficult for a creditor to anticipate and defend itself against all adverse terms in the debtor’s other credit contracts that would divert value away from them. Anticipating this, creditors are more likely to include such adverse terms. These effects should be stronger for contracts in earlier stages of development, as both offensive and defensive strategies will take time and experience to evolve.

Researchers in complex systems have argued that systems designed only for anticipated conditions are inherently fragile. See Steven D. Gribble, Robustness in Complex Systems, Inst. for Elec. & Elecs. Eng’rs (2001), https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.64.4915&rep=rep1&type=pdf [https://perma.cc/G6TH-RCVH].

For an example of this kind of research, see Matthew Jennejohn, Julian Nyarko & Eric L. Talley, Contractual Evolution, 89 U. Chi. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2021), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3810214 [https://perma.cc/9FRN-G2KW].

Thomas Griffin, Gregory Nini & David C. Smith, Losing Control? The 20-Year Decline in Loan Covenant Restrictions (2019) (unpublished manuscript), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3277570 [https://perma.cc/K565-JGDW].

See Kenneth Ayotte & Jared A. Ellias, Bankruptcy Process for Sale, 39 Yale J. on Regul. (forthcoming 2022), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3611350 [https://perma.cc/YQ7R-FL58] (tracing the evolution of lender governance).