Equality’s Frontiers: Courts Opening and Closing

In the 1930s, during the Depression, the federal government funded jobs through the Works Projects Administration (WPA), supporting new construction projects as well as artworks around the country. Hundreds of buildings went up, including a new federal courthouse and post office in Aiken, South Carolina. The art commission went to an artist from the Northeast, who provided a large mural, called Justice as Protector and Avenger, installed behind a judge’s bench in a courtroom.1 (See Figure 1.)

The central female figure is a reference to the Renaissance Virtue Justice—familiar to us all because she is regularly deployed in courthousesaround the world. But the WPA artist explained that his “figure of ‘Justice’” was “without any of the customary . . . symbolic representations (scale, sword, book . . .).” He said that the only “allegory” he had permitted himself was “to use the red, white and blue [of the United States flag] for her garments.”

What did others see? A local newspaper objected to this “barefooted mulatto woman wearing bright-hued clothing.” The federal judge in whose courtroom the mural appeared termed it a “monstrosity”—a “profanation of the otherwise perfection” of the courthouse.

Figure 1.2

The artist protested that observers, if truly impartial, could not conclude “that the figure’s face . . . appears to have negroid traits. I should not only be willing but anxious to obliterate this ‘blemish,’ because I had certainly intended nothing of the sort.” A federal government official from the Department of the Treasury responded, “I must confess that the palette of the head . . . and the vivid red lips . . . would [make it] easy to . . . conclu[de] that the figure is mulatto.”

A “compromise” was proposed to “lighten Justice’s skin color.” But others, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, objected. The denouement was to cover the mural with a tan velvet curtain, seen at the edges of Figure 1.

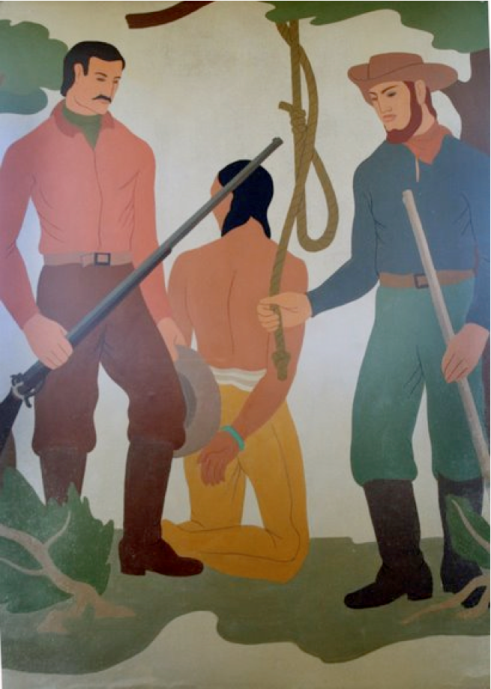

At the same time that the “mulatto” Justice was draped because she was seen to be unsightly, another series of WPA murals were placed on the walls of the Ada County Courthouse in Idaho. (See Figure 2.) A news report later described one scene as an “Indian in buckskin . . . on his knees with his hands bound behind his back . . . flanked by one man holding a rifle, and another armed man holding one end of a noose dangling from a tree.”3

No objections were recorded at the time to this display of a lynching in a courthouse. But toward the end of the twentieth century, a judge in Idaho concluded that the imagery was offensive. The judge ordered that the mural be draped with flags of the state and of the United States.

In 2006, the temporary use of the facility by the legislature (whose own building was under repair) prompted new questions about whether to continue to hide the mural or paint it over. The state legislature, in consultation with Indian tribes, decided instead that the mural should remain in view, framed by official, educational interpretive signs to explain that the picture reflected “the values” held at that time.4

Why start this discussion of equality’s frontiers with pictures from the 1930s? These pictures make a first point—that courts were one of equality’s frontiers. The conflicts about what could or could not be shown on courthouse walls mirrored conflicts about what rights people had in court. In the 1930s, just as a “mulatto” could not serve uncontested as a representation of Justice, people labeled “mulattos” were given little protection in courts as a matter of law.

Figure 2.5

Look then at the next image—a 2010 picture of the current Supreme Court with its nine Justices, including our honoree, the inaugural Gruber Lecturer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. (See Figure 3.) This picture underscores a second point, which is the importance of appreciating the remarkable change that has taken place in the last seventy-five years, during which time courts were reinvented as institutions welcoming all of us. Today, every person—regardless of gender, race, and ethnicity—is authorized to play all roles—from litigant and lawyer to witness and juror to Supreme Court Justice. This idea is both relatively new and deeply radical when held against that 1938 baseline—when a “mulatto” Justice had to be shrouded in drapes because neither state nor federal officials wanted a dark-skinned woman to adorn a courthouse wall.

Figure 3.6

My third point is that getting into court is not the same as being treated as an equal in court. In the 1960s and thereafter, as lawyers were bringing claims against sex stereotyping, they found that some of the presiding judges in their cases shared the very same prejudices and biases as those of the defendants being challenged. To respond, in the late 1970s, the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund created a National Judicial Education Program that the National Association of Women Judges (also founded in the late 1970s) joined. The effort focused on using local examples to help judges see a range of illustrations of the problems women faced. In the early 1980s, the Chief Justice of New Jersey decided to commission a “Task Force” on “gender bias in the courts.”7

Some sixty jurisdictions followed thereafter, producing official reports discussing the treatment of women and men of all colors in state and federal courts. One excerpt, from New Jersey in the mid-1980s, is the placeholder here for thousands of pages of documentation. That report concluded that “stereotyped myths, beliefs, and biases were found to sometimes affect judicial decision-making . . . in domestic violence, juvenile justice, matrimonial law, and sentencing,” and that there was “strong evidence” of differential treatment of women and men in courts and chambers.8 A decade later, in 1996, Justice Ginsburg wrote the foreword to another study, The Report of the Special Committee on Gender, prepared for the federal courts for the District of Columbia. As she put it, the “trend towards greater equality” was by then apparent but so was “the need for vigilance.”9

Turn from the problems of those inside courthouses to the problems of others, standing at the door. Today, we can celebrate that “race, gender, and other incidents of birth” no longer provide formal barriers to courts.10 But we have little to celebrate when considering the impact of class, which, of course, intersects with “race, gender, and other incidents of birth.” As Justice Ginsburg has discussed, unless people have “full purses or political muscle,” they cannot afford to bring cases.11

My fourth point, therefore, focuses on the relationship between the Constitution of the United States and the needs of poor people. The questions—sitting on equality’s frontiers—are about how much governments are obliged to fund courts and to subsidize users—either individually or by facilitating claims brought in the aggregate through class actions or other mechanisms. Yet other questions relate to what claims law recognizes as warranting a hearing on the merits in public before impartial judges.

To turn to a concrete example, consider what happened to Melissa Lumpkin Brooks, or “M.L.B.” as she is known in the annals of the Supreme Court. After a divorce, her husband asked the Mississippi courts to terminate her rights as a mother so his new wife could adopt Ms. Brooks’s two young children. Ms. Brooks lost at trial and wanted to appeal; her argument was that the exacting burden of proof—of clear and convincing evidence that she had neglected or abandoned her children—had not been met. But she could not afford to pay the $2,353.36 for a transcript of the trial and related records below,12 and Mississippi law had no provision for waiving any fees on appeal.13

What does the U.S. Constitution have to say about a poor civil litigant’s right to get an appeal? The Supreme Court held in the 1970s that poverty was not a “suspect classification” under the Equal Protection Clause.14 Further, the Court has held that, to establish a violation of the Equal Protection Clause, a plaintiff has to show intentional discrimination; disparate impact is generally not enough.15

What about the Due Process Clause? In 1971, a landmark opinion required Connecticut to waive a fifteen-dollar filing fee for Gladys Boddie, who was seeking a divorce.16 But, in the years thereafter, the Court said that the Due Process Clause did not require fees to be waived for someone filing in bankruptcy17 or for a person losing welfare benefits and unable to pay Oregon’s twenty-five-dollar fee to review the decision.18 The few cases that have required state subsidies for indigent appellants involve providing funds for criminal defendants to obtain transcripts on appeal.19

Given these Supreme Court decisions, the State of Mississippi argued that Ms. Brooks had no right to more—that a three-day hearing was all the process due, that no intent to discriminate existed, and that requiring a state to “subsidize” Ms. Brooks’s civil appeal would create a “new constitutional right.”20

In 1996, Justice Ginsburg, writing for six members of the Court, disagreed. She refused to resort to what she called “easy slogans or pigeonhole analysis”21 and instead concluded that an amalgam of equal protection and due process principles required the State to provide funds for the transcript on appeal. Equal protection, she wrote, related “to the legitimacy of fencing out would-be appellants based solely on their inability to pay core costs.”22 Due process spoke to the “essential fairness of the state-ordered proceedings.”23 The Court held that the fundamental nature of the right to parent, coupled with the absolutism of the termination order that was supposed to be predicated on clear and convincing evidence, meant that poor litigants could not be left without appellate review.24 On remand, Ms. Brooks’s visitation rights were restored.25

While path-breaking, the judgment in M.L.B. is also very limited. The ruling rests on the unique nature of parental-rights terminations, which are a very small fraction of the family matters before any court. For example, as Justice Ginsburg’s decision recounted, between the years of 1980 and 1996, only sixteen such appeals were filed in the Mississippi courts.26

Consider data from New York State in 2010, when 2.3 million civil litigants were in that state’s courts (in filed cases) but without lawyers. More than ninety-five percent of parents in cases involving child support were unrepresented.27 These high numbers of “pro ses” (proceeding “for themselves”) are replayed throughout the country in state and federal courts. As a consequence, a new effort, called “civil Gideon,” is underway. That movement is named after Gideon v. Wainwright,28 a case celebrating its fiftieth anniversary in 2013. Gideon is famous for its mandate that states must subsidize poor criminal defendants facing felony charges by providing them with lawyers.

Advocates of civil Gideon argue that both state and federal constitutions ought to be read to require lawyers when other fundamental legal issues involving family, housing, or health are at stake. A few states have embraced this idea for certain kinds of cases.

But, in 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court set this effort back.29 The case involved another parent, Michael Turner, who asked that South Carolina provide him with a free lawyer when charged with civil contempt for his failure to pay his child’s mother some $6,000 in support. Turner lost in South Carolina and served a twelve-month sentence. In 2011, Justice Breyer wrote for a majority of the Court that included Justices Ginsburg, Kennedy, Sotomayor, and Kagan. In some respects, the case is a victory in that the group of five joined together to insist on rights to fair process. The Court concluded, over objections from the dissent, that Mr. Turner had a right to “fundamentally fair” procedures and that South Carolina had not accorded him a sufficiently fair procedure. But the Court rejected a reading of the federal Constitution to require that lawyers be appointed for indigent civil-contempt defendants whose adversaries were “private” parties (and in this instance, unrepresented), even if those defendants could end up, like Michael Turner, in jail for a year.30 In the absence of state-funded lawyers, the Court held, states had to provide alternative mechanisms to ensure that civil-contempt proceedings were fundamentally fair. Included on the Court’s list were notice that the question of the defendant’s ability to pay was central, information about how to document income, and “an express finding by the court that the defendant has the ability to pay.”31

Thus far, I have provided examples of involuntary defendants: parents at risk of losing their children or their liberty and individuals in need of various kinds of subsidies. These are not the only needy litigants. Consider also individuals who want to come to court as civil plaintiffs, for example, to stop their evictions or mortgage foreclosures, to argue that they have been subjected to sex discrimination at work, or to claim that the phone company has violated consumer protection laws and overcharged them.

Private lawyers have little interest in representing such people because, if a case is filed individually, the costs are too high and the economic damages too low. The Legal Services Corporation does not have enough lawyers to represent all who meet even its very restrictive eligibility requirements. It is either class actions, other forms of aggregation, civil Gideon—or the cases are not filed at all. Yet in the 2011 Term, the Supreme Court both set back civil Gideon and made it more difficult to file class actions.32

To conclude, let me sketch how the pieces of the narrative I have provided fit together. The project of the twentieth century was to get all of us—everyone—into court and thereby to make true historic promises found in dozens of state constitutions: that individuals have rights to come to open courts to obtain redress for injuries to their persons and property. It is a remarkable achievement that, once the courthouse doors were opened, so many individuals and such a range of individuals have come to court to seek redress. More than fifty million cases (traffic, family, and juvenile cases not included) are filed annually in state courts. One should read that number as a tribute to our democratic court system, in that millions understand courts as a government-provided service to which they can and do turn.

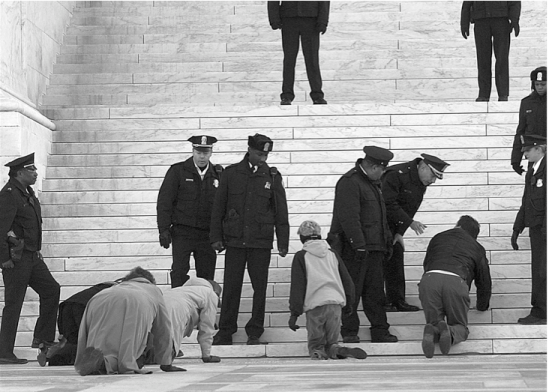

The question for the twenty-first century is what to do with all those now eligible to come to court to try to enforce rights. The answers I have discussed so far are insufficient, for they help a tiny subset of civil litigants. What is needed instead is a broader conception of constitutional obligations founded on deepening the meaning of equality and recognizing the positive relationship between government and its citizenry. Insights into how to fashion its contours come from one last example of Justice Ginsburg’s opinions, again involving courthouse barriers—in this instance, physical barriers. This image captures the problem. (See Figure 4.) The picture shows protesters at the Supreme Court who were demonstrating the challenges that courthouse steps pose for those who have difficulty walking.

Figure 4.33

This demonstration was on the day of oral argument in a lawsuit brought by George Lane, a paraplegic who had literally crawled up stairs in a Tennessee courthouse in order to respond to criminal charges.34 He then filed a lawsuit arguing that the state owed him damages for violations of a federal statute, the Americans with Disabilities Act. Tennessee responded that it had constitutional immunity, as a sovereign, from the damage action.

Five Justices held that the state could be held liable; Justice Ginsburg wrote separately to concur.35 She explained that the Americans with Disabilities Act embodied “not blindfolded equality, but responsiveness to difference; not indifference, but accommodation.”36 The holding is, of course, limited to the Americans with Disabilities Act, just as the M.L.B. decision about rights to state-paid transcripts is limited to parents facing the loss of their rights. But the ideas in both are about the essential function courts play in recognizing and producing the equal citizenship of all persons. Both decisions make plain that formal equality is not enough and that substantive equality can only come through making accommodations that take specific barriers into account. The larger claim is that governments ought to be proud to provide courts as a social service and to subsidize both users and court infrastructure, just as governments fund police services and prisons as well as education, roads, and postal services in efforts to support and to generate functioning and flourishing democratic polities.

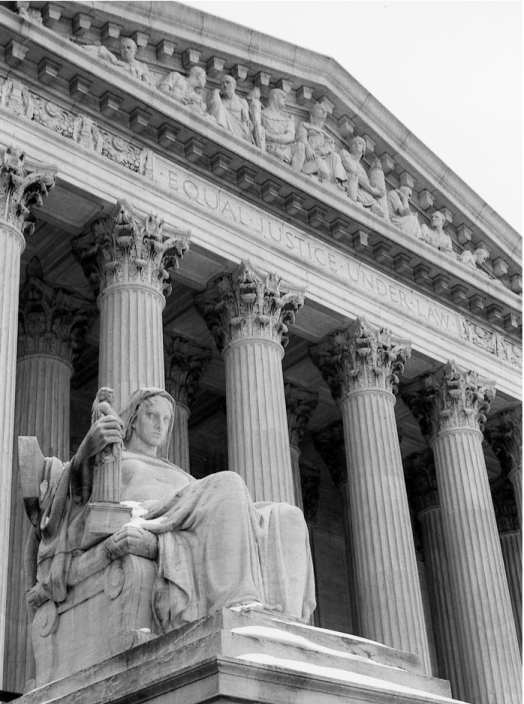

I close then with one final image, which is of the entry to the U.S. Supreme Court. (See Figure 5.) This picture shows the top of the stairs that the Lane protesters were trying to crawl up. Etched at the top of the Court’s entrance are the words “Equal Justice Under Law.” In 1935, when the building opened, those words were aspirational, inscribed decades before all persons were recognized as juridical equals in courts.37

Please read these words as a sign, marking a current frontier whose challenges and contours we are just beginning to appreciate.

Figure 5.38

* * *

Justice Ginsburg offered the following response:

| That was splendid. You’re right that M.L.B. is a very limited decision. It didn’t even say that the mother fighting to be recognized as a parent of her children had a right to a lawyer. The sole question was whether she could be denied the right to appeal a decision terminating her parental status simply because she lacked the money to pay for a transcript of the trial. She didn’t urge the right to have a lawyer because, in fact, she had one—a volunteer lawyer represented her. |

| One of Judge Guido Calabresi’s colleagues, Judge Robert Katzmann of the Second Circuit, has recognized a need for representation by counsel that cries out for attention. It is the problem of immigrants caught in the toils of the deportation (now called removal) process. Often they appear without counsel; sometimes they engage lawyers who deceive them; sometimes their counsel is unable to speak their language. Their plight doesn’t come within the Gideon doctrine because removal proceedings are typed “civil.” M.L.B. makes a small breach in the line between civil cases, in which you don’t get state-paid assistance, and criminal cases, in which you do. Judge Katzmann is making valiant efforts to alert the bar to the plight of the immigrant. His message: if you are truly a member of a learned profession, you will step forward and provide the assistance these people need. |

* * *

Judith Resnik is the Arthur Liman Professor of Law at the Yale Law School and thanks Dennis Curtis, Reva Siegel, and Vicki Jackson for all the many discussions of equality; Laura Beavers, Caitlin Bellis, Edwina Clarke, Jennifer Luo, and Jane Rosen for help in researching these comments; and Justice Ginsburg, for reshaping the opportunities that all of us have.

Preferred citation: Judith Resnik, Equality’s Frontiers: Courts Opening and Closing, 122 Yale L.J. Online 243 (2013), http://yalelawjournal.org/forum/equalitys-frontiers-courts-opening-and-closing.