The Moral Impact Theory of Law

Responses to this Article

abstract. I develop an alternative to the two main views of law that have dominated legal thought. My view offers a novel account of how the actions of legal institutions make the law what it is, and a correspondingly novel account of how to interpret legal texts. According to my view, legal obligations are a certain subset of moral obligations. Legal institutions—legislatures, courts, administrative agencies—take actions that change our moral obligations. They do so by changing the morally relevant facts and circumstances, for example by changing people’s expectations, providing new options, or bestowing the blessing of the people’s representatives on particular schemes. My theory holds, very roughly, that the resulting moral obligations are legal obligations. I call this view the Moral Impact Theory because it holds that the law is the moral impact of the relevant actions of legal institutions. In this Essay, I elaborate and refine the theory and then illustrate and clarify its implications for legal interpretation. I also respond to important objections.

author. Professor of Law and Associate Professor of Philosophy, UCLA; Faculty Co-Director, UCLA Law and Philosophy Program. For valuable discussions and comments on this paper or ancestors of it, I would like to thank Larry Alexander, Selim Berker, Mitch Berman, Jules Coleman, Ronald Dworkin, Les Green, Barbara Herman, Scott Hershovitz, Pamela Hieronymi, Ken Himma, Kinch Hoekstra, A.J. Julius, Frances Kamm, Sean Kelsey, Christine Korsgaard, Brian Leiter, Harry Litman, Andrei Marmor, Herb Morris, Steven Munzer, Derek Parfit, Stephen Perry, David Plunkett, Joseph Raz, Larry Sager, Scott Shapiro, Seana Shiffrin, Scott Soames, Larry Solum, Nicos Stavropoulos, and Jeremy Waldron. I am especially grateful to Andrea Ashworth, Seana Shiffrin, and Scott Shapiro for many invaluable conversations. Special thanks to Ben Eidelson and other editors of the Yale Law Journal for helpful suggestions.

Introduction

In this Essay, I develop an alternative to the two main views of law that have dominated legal thought. My view offers a novel account of how the actions of legal institutions make the law what it is, and a correspondingly novel account of how to interpret legal texts. According to my view, legal obligations are a certain subset of moral obligations.1 Legal institutions—legislatures, courts, administrative agencies—take actions that change our moral obligations. They do so by changing the morally relevant facts and circumstances, for example by changing people’s expectations, providing new options, or bestowing the blessing of the people’s representatives on particular schemes. My theory holds, very roughly, that the resulting moral obligations are legal obligations. I call this view the Moral Impact Theory because it holds that the law is the moral impact of the relevant actions of legal institutions.2

In order to provide an informal introduction to the theory, I begin by illustrating the theory’s account of statutory interpretation and contrasting that account with two more familiar accounts of statutory interpretation (those offered by the two main opposing views of law). I use an example drawn from the well-known case of Smith v. United States.3 Smith had offered to trade a gun for cocaine. The Supreme Court divided over the question whether he was properly sentenced under a statute that provides for increased penalties if the defendant “uses . . . a firearm” in a drug-trafficking or violent crime.

According to a standard account of what statutory interpretation involves, in interpreting a statute, we seek the meaning or, better, the linguistic content of the statutory text.4 This account is assumed without argument by both the majority and dissenting opinions in Smith.5 Smith highlights a serious problem for this account, however. As the contemporary study of language and communication has made clear, there are multiple components and types of linguistic content.6 In Smith, there are at least two types of linguistic content plausibly associated with the statutory text that would yield opposite outcomes in the case. First, there is the semantic content of the statutory text—roughly, what is conventionally encoded in the words. Second, there is the communicative content—roughly, what the legislature intended to communicate (or meant) by enacting the relevant text.7

Trading a firearm is within the semantic content of the phrase “uses a firearm,” so the semantic content yields the result that Smith was properly sentenced. Plausibly, however, Congress intended to communicate that using a gun as a weapon was to receive an increased penalty.8 For illustrative purposes, I will assume that this was Congress’s intention—what Congress meant. Thus, the communicative content yields the result that Smith should not have been sentenced to the increased penalty.

The familiar account according to which interpreting a statute is extracting its linguistic content has no way of adjudicating between multiple linguistic contents of the statutory text. The statutory text in Smith has both a semantic content and a communicative content, and they point in opposite directions. The account therefore offers no answer to the problem posed by Smith’s trading a gun for cocaine.

The opposing account of statutory interpretation associated with Ronald Dworkin’s influential theory of law instructs us to seek the principle that best fits and justifies the statute.9 In Smith, we have two salient candidate principles: that use of a gun for any purpose in connection with a violent or drug crime warrants additional punishment; and that use of a gun as a weapon in connection with a violent or drug crime warrants additional punishment. Both principles fit about equally well—after all, the Supreme Court was sharply divided over which of these two better captured the meaning of the statutory text, and we have noted that both are plausibly linguistic contents of the text. On Dworkin’s account, the question then becomes which principle is morally better—i.e., which principle would, ex ante, be a better one to have.10 Assuming that one principle is better than the other, Dworkin’s account thus does offer an answer to our problem. But the way in which it does so is problematic. At least in general, a straightforward appeal to which interpretation yields a morally better standard does not seem permissible in legal interpretation.

On the account of statutory interpretation implied by my theory of law, we interpret a statute by seeking to discover what impact the enactment of the statute, along with relevant circumstances, had on our moral obligations. Thus, we ask not which rule is morally better ex ante, but which moral obligations, powers, and so on (if any) the legislature actually succeeded in bringing about. What is the moral consequence of the fact that a majority of the members of the legislature, with whatever intentions they had, voted for this text, with its semantic content? Thus, for example, the semantic content and the communicative content of the statutory text are relevant if, and to the extent that, moral considerations, such as considerations of democracy and fairness, make them relevant. It might be argued on democratic grounds, for example, that the fact that popularly elected representatives intended to communicate a particular decision provides a reason in favor of citizens’ being bound by that decision. But the upshot of democratic considerations is a complex matter. A counterargument could be mounted that such a decision is binding on citizens only to the extent that it is encoded in the meaning of the words that the legislature used—mere intentions are not enough. Or it might be argued that, in the actual circumstances of a particular enactment, for reasons of both fairness and democracy, the public’s understanding of a statute’s effect matters more than the legislature’s actual intentions or the meaning of the words. To the extent that moral considerations point in different directions, interpreting the statute will require determining what the moral impact of the statute is, after all of the relevant values have been given their due. And the answer to this question may not correspond to any linguistic content of the statutory text.

It’s worth noticing how natural this account of statutory interpretation is. Return for a moment to the standard account, according to which statutory interpretation seeks the linguistic content of the statutory text. When faced with two or more linguistic contents that are competing candidates for a statute’s contribution to the law, it is very natural to appeal to considerations such as democracy and fairness to try to adjudicate between them. For example, one might try to argue that certain democratic considerations require that the statute be interpreted in accordance with what the legislature intended to communicate, rather than in accordance with the semantic content of the text. Once we have gone this far, it is difficult to resist the conclusion that we need to ask what the moral implications of the statute’s enactment are on balance, that is, taking all of the relevant values into account, as opposed to what certain aspects of democracy or fairness by themselves would support.

I have just sketched a way in which the Moral Impact Theory makes a difference at a relatively practical level—with respect to our understanding of statutory interpretation. Before concluding this Introduction, I would also like to indicate how the theory relates to a larger understanding of law’s nature and, in particular, of what law, by its nature, is supposed to do or is for.11 Often our moral situation is worse than it could be in a particular way—namely, that it would be better if our moral obligations (and powers, and so on) were different from what they in fact are. For example, consider a situation in which a community faces a problem, and there are many different ways to go about solving the problem. For a variety of reasons—for instance, because one person’s efforts toward any given solution would not make a difference without participation by many others—it is not the case that anyone has a specific obligation to participate in a particular solution. But it would be better if everyone did have such an obligation. The legal system can change the moral situation for the better by changing the circumstances so that everyone does have the obligation to participate in a particular solution. Although I will not argue for it here, my view is that it is part of the nature of law that a legal system is supposed to change our moral obligations in order to improve our moral situation—not, of course, that legal systems always improve our moral situation, but that they are defective as legal systems to the extent that they do not.

The Moral Impact Theory fits smoothly into this background understanding of law. Legal institutions take actions to change our moral obligations by changing the relevant facts and circumstances. (In Section II.B., I explore a variety of ways in which they are able to do so.) With important qualifications, the resulting moral obligations are legal obligations. If a legal system is, by its nature, supposed to change moral obligations, it is not surprising that the central feature of law—its content—is made up of the moral obligations that the legal system brings about. Moreover, the view that a legal system is supposed, not merely to change moral obligations, but to do so in a way that improves the moral situation will, as we will see, play an important role in determining which of the moral obligations that result from actions of legal institutions are legal obligations.

Here is the plan for the rest of the Essay. In Part I, I situate the Moral Impact Theory more fully by contrasting it with two dominant views of law. In Part II, I develop the theory, beginning with a rough formulation and gradually refining it. In Part III, I illustrate the theory’s implications for legal interpretation in greater detail than I did at the start. In Part IV, I address two important objections to the theory.

I. situating the theory

The Moral Impact Theory stands in opposition to two dominant views of law. In the Introduction, I sketched the difference between the Moral Impact Theory’s account of statutory interpretation and those of the dominant views. In this Part, I introduce the two opposing views properly and explain briefly how the Moral Impact Theory differs from them.

A few preliminaries. In a jurisdiction like that of the United States or Massachusetts or France there are many legal obligations, powers, privileges, and permissions. I will refer to all of the legal obligations, powers, and so on in a given jurisdiction at a given time as the content of the law.12 (For brevity, when context prevents confusion, I will sometimes simply use the law for the content of the law.13) It is uncontroversial that at least many facts about the content of the law in a given jurisdiction are not among the ultimate facts of the universe.14 Rather, we can explain why those facts obtain in terms of more basic facts, including, of course, facts about what various legal institutions such as legislatures, administrative agencies, and courts did and said and decided. I will use the term determinants of legal content—or determinants, for short—for the more basic facts that determine the content of the law.15

A theory (or view) of law, in the sense in which I use the term, is a constitutive explanation of the content of the law—i.e., an explanation of which aspects of which more basic facts are the determinants of legal content, and of how those determinants together make it the case that the various legal obligations, powers, and so on are what they are.16 An example of the sort of thesis that could be part of a theory of law is the thesis that the content of constitutional law in the United States is constituted by the original public meaning of the text of the U.S. Constitution.

The first of the two dominant views of law is the Standard Picture. According to this vague picture—I hesitate to call it a theory—the content of the law is primarily constituted by linguistic (or mental) contents associated with the authoritative legal texts.17 The Standard Picture is extremely widely taken for granted, and assumed to be common ground (though it is rarely explicitly espoused). In characterizing the Standard Picture, I use the phrase “linguistic content” rather than “meaning” because the latter has multiple senses, and I am trying to get at a particular one—what we might call meaning, strictly speaking.18 Some linguistic contents are constituted by the contents of mental states. For example, on a common view, the speaker’s meaning of an utterance is determined by the content of certain of his or her communicative intentions. Moreover, the Standard Picture is often relaxed to include the contents of other mental states associated with an authoritative text, such as the content of a legislature’s intention to achieve particular legal effects by enacting a statute.

The Standard Picture has deep roots in ordinary thought about the law. A simple version of this picture is encapsulated in the layperson’s idea that the law is what the code or law books say. And among legal philosophers, the Standard Picture is widely taken for granted.19 One reason is that it dovetails with—and indeed fills a gap in—legal positivism, the most widely held position in philosophy of law.20 A central positivist thesis is that the content of the law depends, at the most fundamental level, only on social facts, understood as non-normative, non-evaluative facts.21 But legal positivism does not specify how social facts determine the content of the law. To say that the content of the law is determined, at the most fundamental level, by social facts alone does not yet tell us, for example, how statutes contribute to the content of the law. One manifestation of this gap is that positivism by itself does not yield an account of statutory interpretation—of how to discover a statute’s contribution to the content of the law. How do we get from the fact that a given statute was enacted to the statute’s contribution to the content of the law?

In general, it is a difficult problem to say how practices, decisions, and the like determine unique norms.22 The Standard Picture offers what appears to be an easy solution: the linguistic contents of the authoritative pronouncements are the contents of the legal norms. Moreover, the solution 1) is intuitively appealing to many (as noted, the idea that the law is what the texts say has deep roots in ordinary thought), and 2) requires no appeal to moral or other normative facts. Unsurprisingly, then, the Standard Picture is the standard positivist view with respect to that issue.23 The Standard Picture yields the account of statutory interpretation, discussed in the Introduction, according to which the interpretation of a statute is primarily a matter of extracting its linguistic content—an account that would be accepted by most positivists.

The widespread assumption of the Standard Picture also plays a role in explaining legal positivism’s influence. Unlike positivism, the Standard Picture is typically an implicit assumption that is rarely explicitly acknowledged or defended—and, indeed, it is often assumed to be common ground.24 And the widespread assumption of the Standard Picture biases the debate in favor of legal positivism. Because the Standard Picture holds that the law is primarily constituted by the contents of authoritative pronouncements, it leaves only a limited role that morality could play. All of the anti-positivist options that, given the Standard Picture, are most naturally taken to be available suffer from obvious and serious problems.25

This completes my introduction of the Standard Picture, the first of the two dominant views to which my view is opposed. In sum, the Standard Picture is widely taken for granted, and assumed to be common ground, by contemporary philosophers of law (though it is rarely explicitly espoused).26

The second main view is that of Ronald Dworkin, which, though well-known and influential, is far less widely accepted than the Standard Picture.27 Dworkin conceives of the law as an underlying, idealized source from which all legal practices flow. More specifically, the content of the law is the set of principles that best morally justifies past legal and political practices.28 Dworkin famously explicated the relevant kind of moral justification with his notions of fit and justification.29

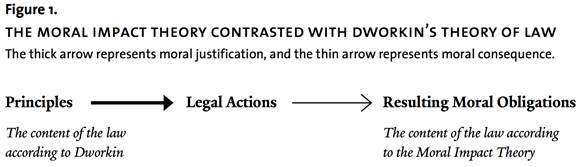

The Moral Impact Theory, like Dworkin’s theory and unlike the Standard Picture, holds that the relation between legal practices and the law is a moral one. But, unlike Dworkin’s theory, the Moral Impact Theory holds that the law is the moral impact or effect of certain actions of legal institutions—i.e., the moral obligations that obtain in light of those actions—rather than the set of principles that best justify them. To use a spatial metaphor, on the Moral Impact Theory (as on the Standard Picture), the law is downstream of the legal practices; on Dworkin’s theory, by contrast, the law is upstream of the legal practices. Figure 1 illustrates this contrast.30

There are several other closely related differences between the Moral Impact Theory and Dworkin’s view. First, the Moral Impact Theory makes no appeal to Dworkinian interpretation—that distinctive form of interpretation according to which the basic question is which interpretation would make the legal system the best it can be, or, more specifically, which principles best morally justify the practices of the system. In fact, according to the Moral Impact Theory, working out the content of the law is not a genuinely hermeneutic enterprise—rather, it involves straightforward moral reasoning about the moral consequences of various facts and circumstances. Second, according to the Moral Impact Theory, the content of the law is a subset of what morality, taking into account all the relevant considerations, requires. By contrast, there is no obvious reason why the set of principles that best morally justifies the actual practices of a legal system would be a subset of what morality requires. Certainly, Dworkin never argues for or even suggests any such claim.31 On the face of it, one might expect that the principles that best fit and justify the actual, often severely morally flawed, practices would be principles that one should not follow, even given the existence of the legal practices. And, in fact, Dworkin accepts that legal requirements may not be moral requirements, indeed that law may be “too immoral to enforce.”32 Finally, the Moral Impact Theory does not license an argument that because a standard would be a morally good one ex ante, it is part of the content of the law. On Dworkin’s view, however, the fact that a principle is more morally justified counts in favor of its being part of the content of the law; moreover, as we saw with respect to the Smith example, whenever the competing candidate principles fit roughly equally well, the fact that a principle is more morally justified is decisive. In sum, though both the Moral Impact Theory and Dworkin’s theory afford morality an important role, they offer very different accounts of the content of the law.

The three views considered here yield very different understandings of legal interpretation as well. The Standard Picture holds that legal interpretation involves answering the question: what is the linguistic content of the legal texts? On this picture, there is little or no role for moral reasoning in legal interpretation, except perhaps when the legal texts explicitly involve moral terms.33

On Dworkin’s view, legal interpretation involves answering the question: which principles best morally justify the legal practices? In terms of the heuristic that Dworkin often used to explain his account of legal interpretation, it involves finding the most morally justified interpretation that sufficiently well fits the legal practices.34 The Moral Impact Theory rejects both understandings of legal interpretation. It takes the question of legal interpretation to be: what is morally required as a consequence of the lawmaking actions? And it does not understand the universe of lawmaking actions to consist exclusively of issuing texts. When the relevant actions do involve issuing texts, the linguistic content of those texts is only one relevant consideration in the calculation of the moral impact of the actions.

The prominence of the Standard Picture and the Dworkinian view may make it seem that there is a stark choice: either legal interpretation does not involve moral reasoning or it involves the kind of moral reasoning that Dworkin spells out—moral reasoning directed at answering the question of which candidate interpretation makes the legal system “the best it can be,”35 to use Dworkin’s phrase. The Moral Impact Theory opens a third way: legal interpretation involves moral reasoning about what is required as a consequence of the relevant lawmaking actions.36

I mentioned in the Introduction one reason that the Moral Impact Theory is a natural position. We can now recognize several other, closely related reasons. First, at least for many theorists, it is plausible that moral reasoning has a place in legal interpretation. But, as mentioned above, it seems wrong to think that the relevant kind of moral reasoning is moral reasoning concerning which interpretation of a legal text would be ex ante morally preferable. The Moral Impact Theory’s account of statutory interpretation allows a role for moral reasoning that is more procedural. We ask about the moral implication of the fact that, say, the legislature enacted a statute or a court decided a controversy in a particular way, not about which interpretation of the statute or judicial opinion would be morally best. As we will see, the fact that a legal institution acted in a particular way can, along with background circumstances, change our moral obligations—for example, making participation in a particular scheme morally obligatory, despite the fact that the scheme is seriously morally flawed.

Second, legal systems treat legal obligations as genuinely binding obligations that are generated by the legal institutions. The Moral Impact Theory vindicates this treatment. It maintains that the legal obligations are the genuinely binding obligations that are generated by the legal institutions. By contrast, on the Standard Picture, the legal obligations are simply constituted by the linguistic contents of the pronouncements of legal institutions. In general, there is no reason to think that such “obligations” are genuinely binding. For similar reasons, legal positivists have struggled to explain the use of the term legal obligation. For example, influential positivists have argued that to say that there is a legal obligation is to say that, from the perspective of the legal system, there is a moral obligation.37 The account thus denies the commonsense view that a legal obligation is a kind of obligation at all. For, on this view, it can be true that one has a legal obligation despite the fact that one has no obligation (as long as the legal system takes one to have a moral obligation).

Third, the Moral Impact Theory makes it easy to explain our dominating concern with law. We generally treat the law not merely as one relevant consideration among many, but as a central concern, indeed as excluding the relevance of other considerations. It is easy to understand why we would have such interest in the moral consequences of the legal practices. If the legal institutions change what we are obligated to do, it is vital to work out that change. By contrast, it is much less easy to understand why we would be interested in identifying the principles that best justify the legal practices (or that make them the best they can be). More precisely, although we might be interested in such principles, for example because of the value of principled consistency, they would be merely one relevant consideration in reaching practical judgments.

A similar point applies to the Standard Picture. The ordinary meaning of the legal texts is obviously a relevant consideration in practical deliberation, but it is hard to see why it would deserve the central and exclusive focus of attention that the Standard Picture gives it. This point is even stronger than it might at first appear because, as noted above, there are typically multiple different types of linguistic and mental content associated with each authoritative legal text. In the case of a statute, for example, there is the semantic content of the text, what the legislature intended to communicate, what the legislature asserted, what the legislature presupposed and implicated, what the legislature would reasonably be taken to have intended to communicate, what legal effect the legislature intended to achieve, and so on.38 Proponents of the Standard Picture typically assume that, without appeal to moral considerations, one type of content can be identified as the onethat constitutes the content of the law.39 But it is unclear why we should be exclusively concerned with one such content. On the Moral Impact Theory, all of the linguistic and mental contents associated with the legal texts are among the factors that are potentially relevant to our obligations. They—and other morally relevant factors—are given whatever relevance they in fact deserve.

II. the theory

In this Part, I develop the Moral Impact Theory in three stages. Section A makes a few preliminary clarifications and refinements. Section B explains, via several examples, how legal institutions can change our moral obligations, thereby creating legal obligations. Finally, Section C clarifies how the theory distinguishes legal obligations from other moral obligations.

We can begin with a rough and incomplete formulation of the theory:

The Moral Impact Theory (version 1): The legal obligations are those moral obligations created by the actions of legal institutions.

On my view, legal institutions take various kinds of actions, such as voting on bills and deciding cases, that change our moral obligations. The resulting moral obligations are our legal obligations.

A. Preliminary Clarifications and Refinements

1. What Do I Mean by Moral Obligations?

My usage of the term moral is relatively standard, but, because the term is used in various ways, I offer brief clarification. The relevant obligations—the ones that, according to my theory, are legal obligations—are simply genuine, all-things-considered, practical obligations.

Let me take the italicized terms in reverse order. First, the relevant obligations are practical ones—i.e., obligations that concern what one should do, as opposed to what one should think or feel.40 Thus, for example, we are not concerned with epistemic obligations, which concern the formation and revision of beliefs. (The law of evidence does not concern what the finder of fact should believe, but rather concerns such questions as what evidence may be presented to the finder of fact and what evidence the finder of fact may consider.)

Second, the relevant obligations are all-things-considered obligations, as opposed to merely pro tanto ones. If one makes a promise to pick up a friend at the airport, and one’s mother becomes severely ill, then taking all of the relevant considerations into account, one should not pick up the friend at the airport. The obligation may still exist, and consequently one might be morally required to apologize or to make up for its breach. In a terminology that has become standard, we can say that the obligation to pick up the friend is, in light of the mother’s illness, merely a pro tanto obligation. By contrast, an all-things-considered obligation is one that, taking all relevant considerations into account, one should fulfill.41

Third, the point of saying that the relevant obligations are genuine is not that there are two types of obligations, genuine ones and non-genuine ones. Rather, the point is to distinguish my usage from what we might call the sociological sense of the term “obligation” (and of other normative terms such as “reason,” “right,” and so on). To say that a group has an obligation to perform some action in the sociological sense is to say, roughly, that members of the group believe that they have such an obligation (and perhaps have other relevant attitudes and tendencies, such as disapproval of people who do not perform the action in question). An anthropologist might say, for example, that for a particular group it is obligatory (in the sociological sense) to follow particular dietary laws.42 The fact that members of a group believe that something is obligatory obviously does not imply that they have any genuine obligation. For instance, the fact that a cult believes that it is obligatory to sacrifice one’s firstborn child does not imply that this action is obligatory. On my theory, what matters is not whether people believe that they have certain obligations, but whether they actually do.43

In my view, genuine, all-things-considered, practical obligations are all-things-considered moral obligations.44 I therefore will often refer to such obligations as moral obligations. (For brevity, I generally omit the qualification all-things-considered.)

2. The Moral Profile

As a shorthand, I have been writing of obligations. But the content of the law includes more than just obligations. For example, it includes powers, privileges, and perhaps permissions. When I write about the way in which legal institutions change our moral obligations, I mean to include the way in which they change our moral obligations, powers, privileges, and so on. I have coined the term moral profile to cover all of these, but, for convenience, I sometimes write “moral obligations” or just “obligations.”45 With this clarification, the theory can be reformulated more precisely:

The Moral Impact Theory (version 2): The content of law is that part of the moral profile created by the actions of legal institutions.

3. Legal Texts Versus Legal Standards

It will be important to distinguish different uses of the term law. As a mass noun, law can refer to the content of law or to the legal system. As a count noun, a law can refer either to an authoritative legal text (such as a statute or ordinance or a provision thereof) or to a legal standard, requirement, rule, or principle. It is this latter distinction that I want to emphasize here.46 An authoritative legal text is a linguistic entity. By contrast, a legal standard is a norm. Texts and norms are fundamentally different kinds of things. A text may express a norm, just as a numeral may express a number or a sentence may express a thought. But a text is no more a norm than the Roman numeral “IV” is the number four or than the sentence “c’est la vie” is the thought that that’s life. (If the distinction is not immediately evident, consider the moral case. No one would confuse the moral norm against causing unnecessary suffering with a sentence or text.) Moreover, it is a substantive claim that the issuance of an authoritative text makes it the case that a legal norm corresponding to the linguistic content of the text obtains.47 Indeed, it is the central thesis of the Standard Picture.

Despite the obviousness of the distinction, legal practitioners and scholars habitually use terms such as statute and provision interchangeably with terms such as rule and standard. The prevalence of the Standard Picture explains these habits. On the Standard Picture, although texts are not norms, there will be a relatively straightforward correspondence between texts and norms.48

The Moral Impact Theory is an account of how actions of legal institutions, including importantly the issuance of authoritative texts, make it the case that legal norms obtain. And, according to the Moral Impact Theory, the relation between texts and norms will be more complex than the Standard Picture would have it.49 Although using terms for legal texts and legal norms interchangeably is harmless in many contexts, in the present context it will be important to distinguish carefully between statutes and norms. To avoid confusion, I will be careful to use statute, provision, and the like exclusively for texts, and to use standard, norm, and the like exclusively for norms. And I will not use law as a count noun without explicit clarification.

B. How Legal Institutions Change the Moral Profile

How can legal institutions like legislatures and courts change our moral obligations? On the Standard Picture, legal institutions issue authoritative legal pronouncements—statutes, judicial decisions, and the like—the linguistic content of which becomes the content of the law simply in virtue of the fact that it was authoritatively pronounced. We can express this idea by saying that, on the Standard Picture, authoritative legal pronouncements change our legal obligations directly.50 This change in legal obligations may, depending on the circumstances, affect moral obligations. Thus, on the Standard Picture, the standard way for legal institutions to change our moral obligations is by directly changing our legal obligations (by issuing authoritative legal pronouncements).

On the Moral Impact Theory, by contrast, the idea is not that legal institutions change the moral profile by changing the content of the law. Any such suggestion would be viciously circular given that, according to my theory, the changes in the content of the law brought about by the legal institutions are to be explained by the changes in the moral profile brought about by the legal institutions. Instead, the idea is that legal institutions change our moral obligations by changing the relevant circumstances (and not by doing so via changes in the content of the law). There are many different tools that legal institutions can use to bring about such changes in the moral profile.

I can best explain with examples. I use them to illustrate ways in which legal institutions can change our moral obligations by changing the relevant circumstances, thus creating legal obligations. The crucial point is that the examples do not involve changing the moral profile by changing the content of the law, but, rather, changing the content of the law by changing the moral profile. I will come back to this point about the direction of explanation below.51

First, the establishment of a legal system and the actions of legal institutions in maintaining security and punishing wrongdoers can make it morally impermissible to use violence. Without a legal system, it may be morally permissible for people to use violence against others who attack or threaten to attack them or their families or allies. Indeed, it may be morally permissible for people to use violence against others who are endangering their well-being in other ways, for example by taking food or water on which they rely. By maintaining a monopoly on the use of force, effectively protecting people against violence, and reliably punishing wrongdoers, a legal system can make violence morally impermissible, except in a very narrow range of circumstances. Notice that, in this example, actions of legal institutions other than the issuance of texts play an important role in improving the moral situation.

Second, given the great moral importance of advance notice of punishment and the indeterminacy—or at least uncertainty—with respect to what punishment is morally appropriate, the punishment of wrongdoers is in general morally problematic without action by legal institutions.52 A legal system plausibly can make punishment morally permissible by giving notice of which morally wrong acts are punishable and what the corresponding punishments will be.

Third, in the punishment example, the actions of legal institutions are able to make determinate and knowable aspects of morality that are otherwise either relatively indeterminate or uncertain. There are many other cases of this and related phenomena. For example, it is clear that agents who break at least some promises have resulting obligations to the promisee, but there is a great deal of uncertainty about what sorts of remedial actions are appropriate with respect to different promises, and it is plausible that there are frequently a variety of different ways in which the remedial obligations can be met.53 Once the legal system provides certain contract remedies, however, people who make promises act against that background, and this can render determinate and certain or otherwise change what is morally required in the event of breach. The case of accidental breach is a nice example. Ex ante, it is unclear and perhaps indeterminate what remedy is morally required if one breaches a promise accidentally. The actions of legal institutions make the remedy for accidental breach of a legally binding promise clear and determinate.54

Fourth, consider the familiar example of a coordination problem.55 It is sometimes important that all or nearly all people act in the same way, though there are several equally good ways in which everyone could act. It is important, for example, that everyone use electrical outlets that meet the same specifications, though there are many different specifications that would work equally well. Suppose a legislature directs everyone to adopt a particular solution. In the simplest kind of case, this action by the legislature may well have the effect of making the specified solution more salient than the others. As a result, given the moral reasons for following the solution that most other people are likely to follow, everyone may now have a moral obligation to adopt the specified solution.

Matters may be more complicated, however. Because of a wide variety of factors—established practices in the relevant industry, early misunderstandings of the legislation by a particularly influential company or by government inspectors, basic features of human psychology, new technological developments not predictable when the legislature acted, and so on–the result of the legislature’s action may be that a solution that is somewhat different from the one specified by the legislature becomes the most salient one. That solution may therefore come to be morally obligatory, despite the fact that it does not correspond to the linguistic content of the statute.

In both kinds of cases, the legislature has changed the moral profile, creating a new moral obligation. On my account, this new moral obligation counts as a legal obligation because of the way in which it came about.

Fifth, to the extent that people have the ability to participate equally in governance, legal institutions can harness democratic considerations to alter the moral landscape. Promises and agreements are a useful analogy. By making promises and entering into agreements, people change their moral obligations. The fact of agreement has moral force. Even if what was agreed on is an arrangement that is seriously morally flawed—a different arrangement would have been much fairer, for example—the fact that the arrangement was agreed on may be sufficient to create a moral obligation.

Similarly, the fact that a decision is reached by a procedure that is part of a system of governance in which everyone has an equal opportunity to participate has moral force. I don’t mean to suggest that people are morally bound by any decision of a legal institution in a democratically constituted government. But to the extent that self-government results in an arrangement, there are moral reasons for people to abide by the arrangement. I will generally refer to such moral reasons as “democratic considerations,” “reasons of democracy,” or the like.

It is a complex matter what democratic considerations support. It certainly cannot be assumed that democratic considerations always translate into some simple formula, such as whatever a popularly elected legislature intended.56 For example, there are familiar ways in which legislatures fail to be accountable to the public.57

According to the Moral Impact Theory, the relevance of democratic considerations does not derive from the history and traditions of our legal system. It is not, for example, that we are seeking principles that fit and justify our practices, and, because those practices happen to be democratic, the relevant principles turn out to be democratic. Rather, it is a general moral truth that, to the extent that people have equal opportunity to participate in procedures of governance, they acquire moral reasons to comply with the decisions that are reached through those procedures. Democratic considerations therefore are relevant in all legal systems, not just those with democratic traditions. Of course, to the extent that a legal system is part of a system of government that does not allow people to participate, it will not be effective at harnessing democratic considerations.

It is worth noting that, as with agreements, democratic considerations can provide moral support for seriously morally flawed arrangements. The fact that the democratic process has settled on a particular scheme provides reasons for compliance with that scheme, even if the scheme is far from the best scheme that could have been chosen.

I want to emphasize that, in appealing to democratic considerations, I do not mean to suggest that there is a general moral obligation to comply with directives of popularly elected representatives in the circumstances of contemporary nations. There is a widespread consensus that there is no such general moral obligation, and I think that the consensus is correct.58 Indeed, I have elsewhere argued that one of the attractions of my account of law is that it explains how legal systems can generate morally binding obligations despite the fact that there is no general moral obligation to obey directives from legal authorities.59 Although there is no such general moral obligation, democratic considerations can reinforce other factors of the sort that my examples illustrate, yielding moral obligations in particular cases. For example, in the case of a coordination problem, the fact that the solution was democratically chosen may add democratic considerations to the other considerations, such as salience, supporting the solution. In general, in real cases, the different kinds of considerations illustrated by the examples often reinforce each other.

Sixth, legal institutions can create moral obligations to participate in specific schemes for the public good, such as paying taxes. Without a legal system, people will have general moral obligations to help others. But there will often be no moral obligation to give any particular amount of money to any particular scheme. For one thing, especially when it comes to problems of any complexity, many different possible schemes are likely to be beneficial, and the efforts of many people are needed for a scheme to make a difference. Nothing determines which possible scheme is the one that people should participate in. In addition, there is no mechanism for people to participate in one common scheme. By specifying a particular scheme and making it salient, creating the mechanism for everyone to participate in that scheme, and ensuring that others will not free-ride, legal institutions can channel the pre-existing, relatively open-ended, moral obligations into a moral obligation to pay a specified amount of money into that scheme.60

Again, the moral obligation that legal institutional action brings about may be to participate in a scheme that is seriously morally flawed. Suppose that it is very important to have some mechanism in place for solving a particular problem, for example, preventing violence or ensuring clean drinking water. Then, if a particular solution has the best chance of being implemented, it may be morally required to do one’s part in that scheme even if it is significantly worse than—for example, more unjust than—the ex ante best solution to the problem. The fact that legal institutions are implementing a particular scheme can make it the case that that scheme has the best chance of being adopted and therefore that it is morally obligatory. Similarly, once a particular morally flawed rule has been widely adopted and relied on, it may be unfair not to follow it. What legal institutions actually do, not merely the linguistic content of their pronouncements, can therefore play an important role. And, as in the case of a coordination problem, the scheme that becomes morally obligatory as a result of legal institutional action may not be one that corresponds to the linguistic content of any pronouncement.

In certain kinds of situations, however, the linguistic content of directives will be morally binding. Court orders directed at specific individuals are a good example. Because of the overwhelming moral importance of having a way of ending disputes peacefully, there are powerful moral reasons to give binding force to such specific orders.61

I should emphasize that I am not suggesting that making a particular scheme salient, creating a mechanism for participation, and preventing free-riding are necessarily sufficient to create the relevant moral obligation. It will depend on all the circumstances. A corresponding caveat applies more generally across the examples.

Seventh, the point about the legal system’s ability to ensure participation is of great general importance. In many situations, one person’s taking action toward some community benefit will be worthless, or nearly so, without the actions of many others. In such cases, if there is no reasonable expectation that others will cooperate, there is likely no moral requirement that a particular person should participate. By using the threat of coercion, legal institutions can ensure the participation of others, thus removing this obstacle to a moral obligation to participate.

Eighth, and finally, the adjudication of cases is another way in which legal actors can change the moral profile. The considerations relevant to the impact of a judicial decision on the moral profile are complex. I will briefly explicate these considerations by sketching how the actual practice of interpreting appellate case law can be explained as the result of the interaction between them.62

To begin with, note that on the Standard Picture, working out an appellate decision’s contribution to the law should be a matter of identifying an authoritative text—which might be only some portion of the judicial opinion—and then extracting its linguistic content. Indeed, at least once the relevant text is identified, interpreting appellate decisions should be no different from interpreting statutes.

Our actual practice is very different. The standards that appellate courts announce and the reasoning that they offer are given substantial attention, but they are far from the end of the story. In deciding how to resolve a new case in light of a past decision (or decisions), a past decision can be distinguished by pointing out that the present case has relevantly different facts, even if the present case falls within the standard apparently announced by the court in the past case. Moreover, the standards announced in the past case can be treated as nonbinding dicta on the ground that they go beyond what was necessary for resolution of the case.

According to the Moral Impact Theory, considerations of fairness support treating like cases alike, so the fact that a case is resolved in a particular way provides a reason for treating relevantly similar cases in the same way in the future. To the extent that we must treat like cases alike, the resolution of cases will generate standards that affect the proper resolution of future cases. On the other hand, at least for many kinds of issues, democratic considerations favor the creation of standards by representative bodies such as legislatures. Thus, there is an apparent tension between these two kinds of considerations.

But treating like cases alike does not warrant privileging the way in which the court explains its decision or the standards that it announces. What matters with respect to treating like cases alike is whether future cases are in fact relevantly similar to the past case, and that is a moral question, not a question of what the court in the past case said. Therefore, treating past decisions as governing only relevantly similar cases—through the practices of distinguishing past decisions and treating the announcement of rules as dicta—can be seen as a way of reconciling the value of treating like cases alike with democratic considerations that militate against courts’ creating general standards.

The situation is more complicated, however. Depending on the legal system’s practices with respect to precedent, the court’s reasoning and any standard that it announces may create expectations and, for that reason, engage fairness considerations. Moreover, even though a court does not represent the interests of constituents in the way that a legislature does, democratic values having to do with public deliberation give weight to a court’s public offering of reasons in support of a standard. Thus, these other aspects of fairness and democracy explain the careful attention given to past courts’ explanations of their decisions.

This concludes my discussion of ways in which legal institutions can change the moral profile. I emphasize two points about the examples. First, even when, as is typical, the relevant action includes the issuance of some kind of text, the content of the law is not determined simply by the meaning of the text. Rather, the content of the law depends on the moral significance of the fact that the legal institution took the action in question (including the issuance of the text). Judicial decisions illustrate this point well.

Second, in the examples, various kinds of action by government officials, not just pronouncements, alter the moral profile. The examples involve, among other things, the actions of legal officials in setting up actual mechanisms for collecting taxes, protecting people from violence, and taking or threatening enforcement action against shirkers to enforce people’s participation in collective schemes.

As noted, my examples involve actions by legal officials. But how does the legal system instigate appropriate action by officials? If the legal system gets legal officials to act by instructing them to do so, and if such instructions generate legal obligations to act as instructed, then does my account tacitly assume at least some part of the Standard Picture’s understanding of how legal obligations are generated?

This objection is off target. A preliminary point is that officials often do not need to be specifically instructed how to act. Legislators propose legislation, vote on bills, and so on without legal instructions specifying what legislators are to do. Similarly, courts and executive officials take a wide range of actions without specific instructions.

More importantly, although authoritative pronouncements, such as statutes, regulations, and executive orders, are an important part of the way in which a legal system gets officials to act, this use of authoritative pronouncements is not in tension with my theory. As noted above, for familiar reasons, ordinary citizens in contemporary nations, even democratic ones, do not have a general moral obligation to do what the legislature or other legal institutions command.63 Government officials are an important exception, however. The moral obligation of officials is generally overdetermined. They have explicitly consented to the government, have voluntarily assumed an obligation to carry out the instructions of their superiors, and have accepted benefits that they could easily have declined. Therefore, unlike the situation with respect to ordinary citizens, the legal system can typically generate moral obligations of government officials simply by specifying what they are required to do. And those moral obligations, on my account, are legal obligations.

Even in such circumstances, however, the Moral Impact Theory affords authoritative pronouncements a role that is crucially different from the one envisioned by the Standard Picture. According to the Standard Picture, legal obligations come about simply because the relevant content is authoritatively pronounced. By contrast, on the Moral Impact Theory, when circumstances obtain in which authoritative pronouncements are capable of generating corresponding moral obligations, the pronouncements change the content of the law via a change in the moral profile. For example, an executive order directing legal officials to act generates a moral obligation for those officials to act accordingly. This moral obligation comes about not simply because the order was authoritatively issued, but also because of the morally relevant background circumstances—for example, that the officials have voluntarily assumed an obligation to obey, have accepted benefits, and so on. The consequent moral obligation is a legal obligation, so the explanation of the legal obligation goes through the relevant moral considerations.

More generally, there are special circumstances in which commands do generate moral obligations to do what is commanded. That the person commanded is an official of the legal system is simply one such special circumstance. When the relevant circumstances obtain, authoritative pronouncements provide a shortcut for a legal system. The legal system can use such pronouncements to generate moral obligations—and these moral obligations, according to the Moral Impact Theory, are themselves legal obligations. In sum, legal systems can use diverse tools to generate moral obligations. Those tools include, under appropriate circumstances, authoritative pronouncements.64

I hope that the examples have clarified the point that I highlighted earlier about the direction of explanation. It is not that a legislature or court pronounces a norm, which thereby becomes a valid legal norm, and, because of moral reasons for obeying the law, ultimately gives rise to a genuine (moral) obligation. The order of explanation between the legal obligations and the moral obligations is reversed in my account: the legislature votes or the court decides a case, thus possibly creating genuine obligations through the kinds of mechanisms I have been illustrating. Those genuine obligations then are legal obligations.

The examples also are suggestive of what law and legal systems, by their nature, are supposed to do or are for.65 In many of the examples, it would be better if people’s obligations were different from what they in fact are, and the actions of legal institutions have the potential to improve matters by changing the relevant circumstances, thus changing moral obligations. As mentioned in the Introduction, my view (which I do not argue for in this Essay) is that it is part of the nature of law that a legal system is supposed to improve our moral situation in the kind of way that I have described—not, of course, that legal systems always improve our moral situation, but that they are defective as legal systems to the extent that they do not.

C. Clarifying Which Moral Obligations Are Legal Obligations

Thus far, I have written informally of that part of the moral profile created by legal institutions. We need to do more to pin down which moral obligations are legal obligations.

1. Pre-Existing Moral Obligations

In some instances, legal norms have content that is the same as, or at least similar to, that of pre-existing moral norms. For example, the criminal law includes many legal obligations, such as obligations not to harm or kill other people, that have content closely related to moral norms that exist independently of the law. Thus, it might be thought that the relevant moral obligations are not created by the actions of legal institutions and therefore are not legal obligations. In that case, the Moral Impact Theory would have the consequence that some of what we take to be paradigmatic legal obligations, such as the obligation not to kill, are not legal obligations at all.

The needed refinement is that we must understand “that part of the moral profile created by the actions of legal institutions” to include obligations that are altered or reinforced by the actions of legal institutions. (Rather than rewording the official statement of the theory, I will simply stipulate this clarification.)

I begin with obligations that are altered. When a legislature enacts a criminal prohibition on conduct that is already morally prohibited, the legislature’s action typically alters the content of the obligation.66 There are at least two kinds of alterations in content—changes in the first-order content of the obligation, and changes in the remedies available in case of a violation. Consider the case of statutory rape. Before action by legal institutions, the content of the moral prohibition will be relatively vague, perhaps something along the lines of: sex with children is prohibited. Once the legal institutions have acted, the content of the prohibition will typically be much more precise. For example, the actions of the legislature may result in a precise age of consent. The content may become more precise in various other ways, for example, with respect to whether the prohibition applies to everyone or only to adults, whether the sex of the victim and perpetrator matter, whether there are exceptions for marriage, and so on.

Next, legislative action will also typically alter the remedies or punishments for a violation of an obligation. Morality tends to be rather vague about remedies. In the case of punishment, perhaps morality says that a punishment must be proportional to the wrong, but offers little precise detail about what punishments would be proportional to specific wrongs. Indeed, as I suggested above, in part because of this indeterminacy, punishment is in general morally problematic without action by legal institutions. An important way in which legislation alters pre-existing moral obligations is therefore by making determinate the appropriate punishments for violations of those obligations. (I address below the related issue of eliminating uncertainty about moral obligations that are in fact determinate.) Legislation can thus make it morally permissible to punish violators.67

In addition to altering pre-existing moral obligations, a legislative enactment of a criminal prohibition (on conduct that is already morally prohibited) typically results in new reasons for not engaging in the relevant conduct. The examples discussed above are relevant here. For example, the legislative action will often add reasons of fairness and democracy to the pre-existing moral reasons. When reasons are added for engaging in conduct that is already obligatory, let us say that the pre-existing obligations are reinforced.68 The Moral Impact Theory holds that moral obligations that are reinforced by the actions of legal institutions are among the moral obligations that are legal obligations.

2. The Legally Proper Way

The next refinement of the theory is that legal obligations are not just any moral obligations that are created by the actions of legal institutions. We need to limit the relevant moral obligations to ones that come about in the appropriate way—what I call the legally proper way.69 We have an intuitive understanding of the legally proper way for a legal system to generate obligations, and we can articulate it theoretically by appealing to what legal systems are for or are supposed to do. Let me explain. Suppose a government persecutes a particular minority group. This persecution may include directives to harm members of that group or to deny them benefits. Such government actions are likely to have the effect on the moral profile of producing an obligation to protect or rescue the minority group, to disobey the directives, to try to change the policy, and so on. It is intuitively clear that an obligation that comes about in this way is not a legal obligation, despite the fact that it is the result of actions of legal institutions.

The example suggests a necessary condition on the legally proper way for legal institutions to change the moral profile. If legal institutional action, by making the moral situation worse, generates obligations to remedy, oppose, or otherwise mitigate the consequences of the action, such obligations to mitigate have not come about in the legally proper way. Call this general way of changing the moral profile paradoxical (because the resulting obligations run in the opposite direction from the standard case). Moral obligations that are produced in the paradoxical way are not legal obligations.

It is important to note that legal institutional action that generates moral obligations in the paradoxical way may also generate other moral obligations that are legal obligations. For example, Proposition 13, the 1978 California ballot initiative that restricted property taxes, made the moral situation worse and may therefore have generated moral obligations to try to repeal it, but it nevertheless generated legal obligations concerning the assessment of property taxes.70

The necessary condition I have sketched matches our intuitive understanding of the way in which legal systems are supposed to generate obligations, and it is not ad hoc. As I mentioned above, on my view, a legal system, by its nature, is supposed to change the moral situation for the better. This understanding of what legal systems are supposed to do, or what they are for, explains why moral obligations that are generated in the paradoxical way are not legal obligations. The key idea is that, for an institution that, by its nature, is supposed to improve the moral situation, a method that relies on creating reasons to undo what the institution has wrought is a defective way of generating obligations.71 I have illustrated my suggestion that we can use our understanding of what law and legal systems are supposed to do to explain which ways of generating obligations are legally proper—and therefore which obligations are legal. But I do not have a complete account of the legally proper way; further work is needed.72

The Moral Impact Theory (version 3): The content of law is that part of the moral profile created by the actions of legal institutions in the legally proper way.

3. What Makes Something a Legal Institution

Because my formulation of the theory uses the term legal institution, I want to conclude this Part by addressing briefly the question of what makes something a legal institution.73 Although it is not the goal of the Moral Impact Theory to provide a theory of the nature of legal systems and institutions, I will offer a necessary condition. An important part of what it is to be a legal institution is to be part of a legal system, so an account of the nature of legal institutions depends on an account of the nature of legal systems. On my view of law, again, it is essential to legal systems that they are supposed to improve the moral situation. Therefore, a necessary condition on a legal institution is that it be an organization that, by its nature, is supposed to improve the moral situation.74 (Again, the claim is not that legal institutions always improve our moral situation, but that they are defective to the extent that they do not.) This point explains, for example, the fact that an organization of powerful thugs that controls a community is not a legal system or a legal institution. It is no part of the organization’s nature that it is supposed to improve the moral situation. Scott Shapiro makes a similar argument in Legality.75

The foregoing is one necessary condition on legal systems and institutions; there are certainly other necessary conditions. It is not my purpose here to develop a complete account—the Moral Impact Theory is consistent with a range of accounts, and others have done important work on this topic. For example, Joseph Raz argues that legal systems are distinguished from other institutionalized systems by their claiming authority to regulate any type of behavior and by their claiming to be supreme.76 Shapiro argues that Raz’s analysis fails to capture the relevant distinction; he offers, instead, the thesis that a legal system must be self-certifying, i.e., “free to enforce its own valid rules without first having to establish their validity before some superior official or tribunal (if one should exist).”77

Finally, at least in mature and stable legal systems, uncertainty about what a legal institution is will not in practice lead to much uncertainty about what the law is. For, in practice, there is a great deal of consensus about which institutions are legal institutions. (In immature or unstable legal systems, where there is uncertainty about what the legal institutions are, the Moral Impact Theory predicts that there will be uncertainty about what the law is.) It’s also worth noting that, as Raz and Shapiro note, it is plausible that the features that distinguish a legal system (or institution) from other systems are a matter of degree.78 Unsurprisingly, there will be borderline cases.

III. the moral impact theory and legal interpretation

The outline of the theory is now complete. In this Part, I examine the implications of the Moral Impact Theory for legal interpretation.79 In Section A, I return to the example drawn from Smith to illustrate in greater detail the implications of the idea that legal interpretation involves working out the moral consequence of the relevant facts. In Section B, I look at the way in which the Moral Impact Theory explains the relevance to legal interpretation of factors other than actions of legal institutions, such as canons of construction. Finally, in Section C, I clarify and qualify the idea that legal interpretation may require developing an ambitious moral theory.

A. A Statutory Interpretation Example

Recall that, in Smith, the defendant offered to trade a gun for cocaine.80 He was convicted of drug trafficking crimes and sentenced under 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1), which provides for the imposition of augmented penalties if the defendant “during and in relation to any crime of violence or drug trafficking crime . . . uses . . . a firearm.” The Supreme Court, over a vigorous dissent, held that trading a gun satisfied the statutory requirement and therefore affirmed Smith’s conviction.

The Court’s majority and dissenting opinions both regard the question as whether the statutory language—“uses . . . a firearm”—has the effect of making the specified penalty applicable to one who trades a firearm for drugs. The opinions appeal to diverse considerations in support of their opposing positions: the “ordinary meaning” of the word “use”;81 dictionary definitions of the word;82 what people ordinarily mean by words or phrases in particular contexts or how words ordinarily are used;83 how Congress intended the language to be construed;84 how the statutory phrase is most reasonably read;85 whether Congress would have wished its language to cover the situation;86 whether Congress intended the type of transaction to receive augmented punishment;87 the purpose of the statute;88 how the word “used” is employed in the United States Sentencing Guidelines;89 case law;90 other provisions in the same statutory scheme;91 the history of the statute’s modification over time;92 and the rule of lenity.93

For all these claims about relevant considerations, the majority and dissenting opinions strikingly lack both an account of why the relied-upon considerations are relevant94 and an account of how much weight each deserves—or, more generally, of how to adjudicate between the considerations when they point in different directions. These two points are closely related: without an understanding of why considerations are relevant in the first place, it is difficult to know how to reconcile conflicts between them.95

Recently, two philosophers of language, Stephen Neale and Scott Soames, have (separately) pointed out that the Court’s opinions in Smith are marred by mistakes about language and communication.96 Most significantly, the Justices seem unaware of the important distinction between the semantic content of a sentence (roughly, what is conventionally encoded in the words) and what a person means or intends to communicate on a particular occasion by uttering the sentence (and might be easily understood by ordinary hearers to so intend).97 I will use the term communicative content for this latter notion. Soames and Neale share a central point: although the meaning of the word “use” certainly includes trading, Congress, by employing the sentence in question, may well have intended to communicate that the specified penalties cover only the use of a gun as a weapon.98 Both assume without argument that the law is determined by the communicative content of the statute, not its semantic content.99

Thus, despite all their sophistication about language, both philosophers are ultimately in the same position as the Court. They point to a plausibly relevant determinant of the content of the law—communicative content—that they favor, but they offer no framework for explaining why it is relevant or why it should trump other putative determinants.

As I now explain, the account of legal interpretation that derives from the Moral Impact Theory supplies what is missing.100 First, it offers an account of the possible relevance of the diverse candidate factors mentioned by the Court’s opinions, as well as the one favored by the philosophers of language. Second, this account of why factors are relevant yields an account of how potential conflicts between sources are to be resolved.

On the Moral Impact Theory, a statute’s contribution to the content of the law is, roughly, the impact of the fact of the statute’s enactment on the moral profile. In interpreting a statute, therefore, a fact is relevant because it has a bearing on the statute’s impact on the moral profile. A fact might, for example, be relevant because it is a morally relevant aspect of the enactment of the statute (or evidence of such a morally relevant aspect) or because it is a background fact that affects the enactment’s impact on the moral profile. In other words, moral considerations explain why various factors are relevant.

Considerations of democracy and fairness provide explanations of why the various factors mentioned by the Court in Smith are (or would plausibly be thought to be) relevant. For example, the relevance of how Congress intended the language to be construed, whether Congress would have wished its language to cover the situation, how the statutory phrase is most reasonably read, what Congress intended to communicate, and the purpose of the statute are all plausibly explained by democratic considerations. What about dictionary definitions and ordinary usage? Dictionary definitions and ordinary usage are plausibly evidence of how the statutory phrase is most reasonably read or what the legislature would have reasonably been understood to be intending to communicate. And considerations of both democracy and fairness arguably make those factors relevant. Similarly, fairness helps to explain the basis of the rule of lenity and the relevance of decisions of past cases (because of the importance of treating like cases alike).101

It is worth noting how natural it is to appeal to democracy, fairness, rule of law, and other moral values to provide such explanations.102 For example, textualists often appeal to democratic values to support the view that the intentions of legislators or framers, to the extent that they are not expressed in the text, are not relevant to statutory or constitutional interpretation.103 And, similarly, intentionalists argue that democracy supports their view that what matters is the legislators’ intentions.104

The Moral Impact Theory offers not just an account of why various factors are relevant, but, more importantly, an account of how conflicts between relevant factors are to be resolved. On the Moral Impact Theory, the contribution of a statute to the content of the law will depend on the on-balance best resolution of conflicts between moral considerations. Morality provides answers to questions of how conflicts between competing considerations are to be resolved, for example, by determining how much weight competing considerations deserve. In this respect, it differs from a miscellaneous collection of considerations. If one asks what action is supported by, say, considerations of health, efficiency, and aesthetics, then, assuming that there is any conflict between the specified considerations, the question is incomplete because one has not specified how the considerations are to be weighed against each other. The Moral Impact Theory holds not merely that we are to take into account moral considerations, but also that we are to give to each consideration the relevance that morality in fact gives it. (I do not mean to suggest that morality always provides a unique answer to every practical question. There may be much indeterminacy.) Competing democratic considerations may, for example, have different implications for which aspects of the statute are relevant. Or considerations of democracy and considerations of fairness might point in different directions in a particular case. According to the Moral Impact Theory, the correct resolution of such conflicts depends on what the relevant moral values, on balance, support.

Again, we can illustrate with Smith. Here is a useful, if somewhat simplified, way of understanding the fundamental disagreement between the majority and the dissent. The majority believes, roughly speaking, that the interpretation of the statutory provision is determined by its semantic content. The dissent, though it does not understand the distinction between semantic content and communicative content, is groping for the position that the interpretation of the statute is determined by what Congress intended to communicate or perhaps by what one who had uttered the words of the statute would typically have intended.105 As noted above, these positions, by themselves, offer no way forward. One side insists that the words of the statute, as written, straightforwardly cover using a gun to trade, and the other side argues that Congress probably used the words intending to communicate that using a gun as a weapon subjects a defendant to the specified sentence.

According to the Moral Impact Theory, in order to adjudicate between these positions, we need to develop the understandings of democracy (or other moral considerations) that would support these different positions and then determine which is the better understanding of democracy. One democratic consideration might support the idea that what matters is not the actual intentions of particular legislators, but only what is specifically encoded in the language that is voted on by the legislature. A different aspect of democracy might support giving decisive weight to the legislature’s actual communicative intentions. Because, according to the Moral Impact Theory, the correct resolution of the conflict depends on the best understanding of all the relevant considerations, resolving the conflict requires developing an account of democracy.106

B. The Relevance to Statutory Interpretation of Factors Other than Actions of Legal Institutions