The Prison Discovery Crisis

abstract. For incarcerated people litigating pro se, the civil discovery process is vitally important. When imprisoned litigants lack meaningful access to discovery, their cases become swearing contests they are bound to lose, and wrongdoing in prison goes unaddressed. Yet for these same plaintiffs, civil discovery is defunct. The vast majority of incarcerated plaintiffs, including those with promising or meritorious claims, are unable to navigate either to or through litigation’s discovery phase. Part diagnosis and part treatment, this Article is the first to explore in depth how the discovery process fails those pursuing civil-rights claims against their jailers, revealing both a crisis in prison litigation and a failure of our procedural regime.

Relying on both case research and extensive interviews with federal judges, staff attorneys, prison-rights lawyers, formerly incarcerated people, and prison officials, the Article chronicles prison discovery’s written and unwritten rules and their failures. It begins with the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which map awkwardly or not at all onto prison litigation. It then discusses the much broader amalgam of practical impediments to evidence gathering in prison. These include information asymmetries, resource disparities, and hostility between prison defendants—who create and control most of the evidence relevant to incarcerated people’s claims—and plaintiffs.

The Article then scrutinizes the dockets and filings of two hundred recent federal cases arising out of two prisons in two quite different districts: Angola in the Middle District of Louisiana and Menard Correctional Center in the Southern District of Illinois. This research reveals differences between the districts’ case-management decisions and cultures, resulting in startling disparities in prison litigants’ discovery prospects. Incarcerated litigants’ current chances of evidencing and vindicating claims may be largely contingent on the district in which their prison sits—what some incarcerated people call “justice by jurisdiction.” Arguing that this situation is both untenable and preventable, the Article suggests multiple concrete avenues for reform.

author. Law Clerk, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. The views expressed in this piece are my own and do not reflect those of my employer. I am deeply grateful to the formerly incarcerated people, prison officials, judges, and others who agreed to talk with me for this project. For feedback on drafts, I am indebted to Maureen Carroll, Nathan Cummings, Nora Freeman Engstrom, Brianne Holland-Stergar, Amalia Kessler, Margo Schlanger, Joanna Schwartz, David Sklansky, Joshua Stein, and Sergio Valente. For helpful conversations, I want to thank Haller Jackson, Emma Kaufman, Alan Lepp, Martin Martinez, Debbie Mukamal, Norm Spaulding, Robert Weisberg, and Samuel Weiss. Thanks too to the Deborah L. Rhode Center Fellows and those at the Ninth Annual Civil Procedure Workshop at U.C. Law San Francisco for feedback; to Tom Bruton, Clerk of Court for the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, who helped me access case filings; and to Jessica Boutchie and others at the Yale Law Journal for their contributions to this piece. Any errors are my own.

“I can’t fight what I can’t see, and I can’t see what you won’t show me.”

—Kimberly Haven, former jailhouse lawyer1

Introduction

On May 17, 2017, Willie Berry, Jr. sued Nicholas Sanders, a prison guard at Louisiana State Penitentiary (commonly known as Angola). According to Berry’s neatly handwritten complaint, Sanders was called to Berry’s cell on July 12, 2016, to “manage a minutes-earlier unruly conflict” between Berry and a nurse named Tequila Parker.2 Berry had spilled a cup of water on Parker’s leg after a pill envelope she tried to hand him slipped to the floor.3

Sanders arrived and demanded that Berry strip.4 As Berry did so, Sanders sprayed his naked body with “burning chemicals” for three to four seconds.5 And while Berry gagged and writhed on the ground, Sanders yelled: “Bitch, I’m going to make you feel fire, for throwing a cup of water at my baby!”6 Berry yelled for Sanders to activate his body camera, which Angola required guards to use during “serious incidents.”7 Sanders did not.

Five hours passed before Berry could wash the chemicals off his body and get into new clothes.8 Cleaned up, Berry had finally returned to his cell when Sanders came for a second visit.9 This time, it was “to confer.”10

“[T]hat was my baby you got into it with, and I had to show out . . . for her,” Sanders said.11 Then, he made an offer: he would sneak Berry additional food trays and tone down a disciplinary report he was writing about the incident.12 The catch? Berry would just have to agree not to file a prison grievance about what had happened.13

Berry declined.14 His burns remained painful enough the next day that he returned to the doctor, who prescribed pain medication.15 And two weeks later, he filed a grievance against Sanders.16 Months passed without a response.17

Then, around 11:00 AM on October 13, 2016, Sanders returned to Berry’s cell, having gotten word of Berry’s grievance.18 Sanders ordered Berry to be “restrained for a cell inspection,” and once Berry was handcuffed to his cell’s bars, Sanders entered and punched him repeatedly.19 Sanders made no official record of the incident.20

Two months later, Berry filed his complaint pro se.21 He alleged excessive force, retaliation, and denial of equal protection in violation of the First, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments.22 He added some state tort claims, and, in addition to damages, he sought an injunction to force the prison to have “all stationary cameras, that are already fixated on the walls of the Camp J lockdown units, able[] to record, just as other cameras do throughout most of LSP’s units.”23

Berry’s case was first dismissed because he had not paid a $4.47 filing fee.24 After prison bank records proved his indigence, the court let him proceed.25 Berry then survived Sanders’s motion to dismiss his complaint for failure to state a claim.26 Discovery began, and a few months in, Sanders filed a summary-judgment motion.27 The two sides relied on competing affidavits. Sanders claimed that Berry flung a “clear liquid substance on the nurse”; that Sanders arrived and ordered Berry to come to the bars to be restrained, which Berry refused to do; that after repeated warnings and profanity-laden refusals, Sanders sprayed Berry with “only enough chemical agent to gain [Berry’s] compliance and restrain” him, offered Berry a shower and a clean jumpsuit, and notified doctors that Berry needed to be seen.28 Sanders denied visiting Berry at all on October 13, 2016.29 Contrarily, Berry repeated his own account and provided a supporting affidavit from someone four cells over who had heard the altercations.30 Noting the dispute, the judge denied summary judgment.31 The case was bound for trial.

In discovery, Berry was an unusually capable prison litigant. He received answers to interrogatories and got the prison to produce his disciplinary report, medical records, some prison policies, and logbooks from the days in which Sanders allegedly visited his cell; Sanders’s lawyer also deposed him.32 Though Berry requested it, no video-surveillance evidence existed; if any cameras were recording, the prison’s policy was to delete footage after thirty days.33

The documents Berry received were mostly unremarkable. Unsurprisingly, medical records confirmed Berry’s injuries in July and October but revealed nothing about who caused them.34 And unsurprisingly, Sanders’s disciplinary report supported Sanders’s story, while Berry’s affidavit and deposition testimony supported his own.

But two records—actually, the same record produced two times during discovery—let slip a disturbing discrepancy. Twice, the prison produced notarized copies of logbook pages reporting who had visited Berry’s cell block on October 13, 2016: once in June 2018, in response to a court order that the prison produce its internal records related to Berry’s grievance,35 and again in March 2019, in response to Berry’s independent discovery request that the defendant produce the same logbooks.36 Each time, the prison’s production bore a notarized claim to be “TRUE AND CORRECT copies of the originals that are maintained at Louisiana State Penitentiary.”37 The two are produced below.

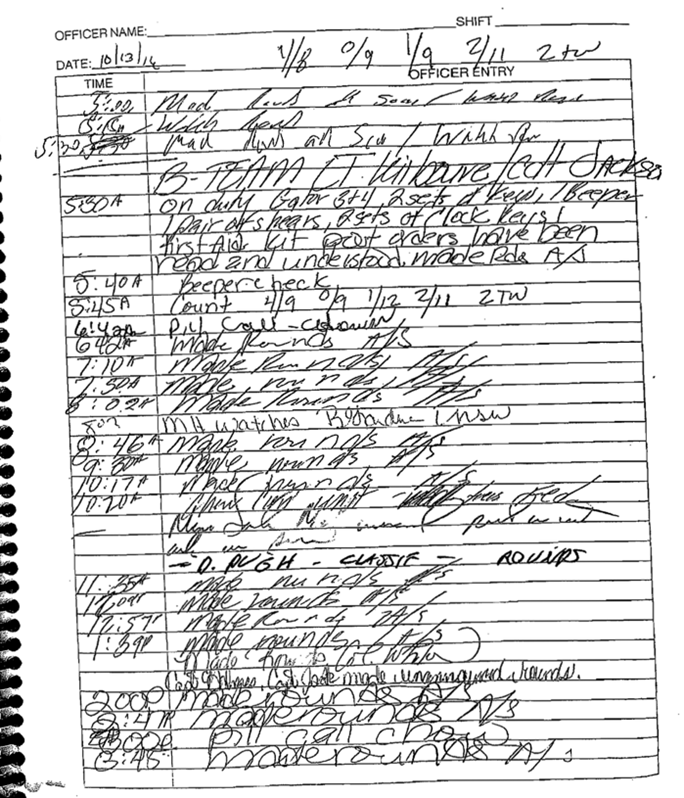

figure 1. earlier copy38

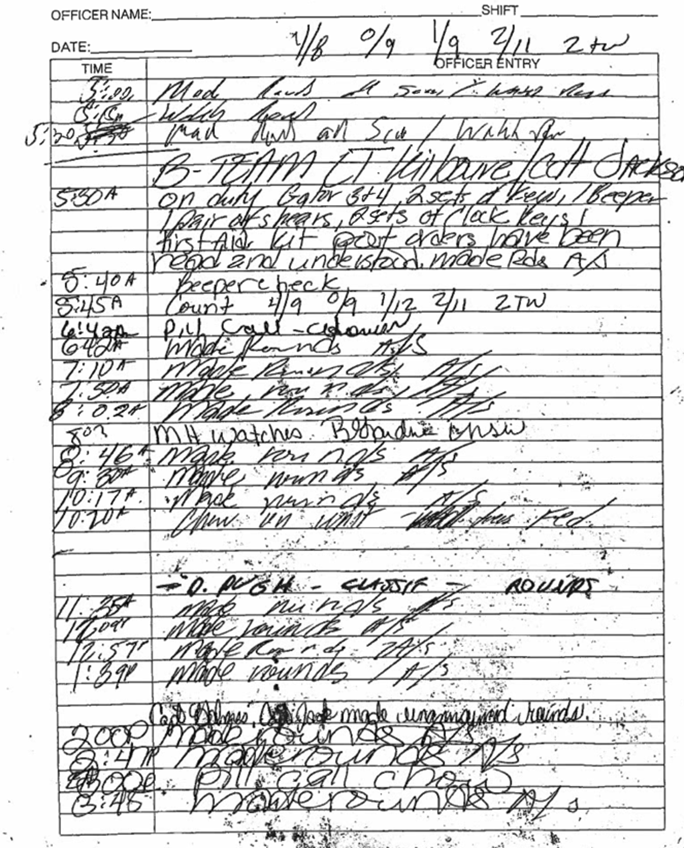

figure 2. later copy39

Do you catch the differences? Berry did. The first copy of the log bears the date; the second does not. More ominously, the first log bears an (admittedly illegible) entry between 10:20 AM and 11:35 AM; that entry has disappeared in the second log. In other words, an entry relaying something that occurred in Berry’s unit, at the exact hour he alleged Sanders beat him up, had been erased between when the prison produced the logbook in June 2018 and in March 2019—while the prison’s guard faced civil liability. Both logbooks bore official seals claiming to be true records.

Berry lost the trial. He showed the jury the logbooks’ discrepancies, but, as the court noted in rejecting his request for a new trial, “the jury’s verdict was essentially a credibility determination . . . and the jury found Defendant’s testimony and evidence more credible than Plaintiff’s.”40 This result did not keep the court from expressing “grave concerns regarding the LDPSC’s conduct,” noting that it “potentially impacts hundreds of prison litigation cases spread across all sections of this Court.”41 The court, in its earlier ruling addressing the logbook discrepancy, had noted that “such records are introduced as evidence on a near-daily basis in this District” and that “to protect the integrity of the judicial process . . . additional inquiry is required.”42 Accordingly, the court ordered the Louisiana Department of Corrections to preserve and turn over the official logbook, which the judge would review in camera.43 Berry’s case, however, was finished.44

***

Civil discovery is vitally important for incarcerated plaintiffs.45 Without it, their cases become “swearing

contest[s]” that they are bound to lose, up against “both judges and juries

[who] tend to find convicted criminals unappealing and unbelievable

witnesses.”46 Discovery

provides the means to scale this credibility wall. And discovery tools—from

interrogatories to requests for production to depositions to expert reports—are

vital disinfectants in prison, where casual brutality and cruelty frequently go

unchallenged. Ensuring that incarcerated litigants

have meaningful access to these information-forcing tools is necessary both for

helping plaintiffs prove their claims and for exposing, addressing, and

deterring systemic problems in a prison system rife with them.47

But does discovery work for imprisoned plaintiffs? Few sources address the question, and those that do paint a dire picture. Take William Bennett Turner’s 1979 article in the Harvard Law Review, which announced the damning results of his study about prison suits under 42 U.S.C. § 1983:

In discovery, answers to interrogatories were obtained in only three [of 664] pro se cases; requests for admissions were answered in only one such case. Pro se litigants failed to obtain production of any documents and did not take any depositions. A medical examination was obtained in one D. Vt. case with an appointed attorney and in no other case.48

Nor, apparently, has the situation improved much in the decades since. A 1997 study by the American Bar Association (ABA) revealed that of twenty district judges surveyed, “twelve said that 50% or more of the prisoners whose complaints survive motions to dismiss and/or for summary judgment cannot adequately process their lawsuits through the discovery stage,” and “significant qualifications” attended the responses of four of the eight judges who responded differently.49 Though these responses were not enough to support conclusions “with any level of precision,” the ABA study’s conclusion was unsurprisingly dour: “[T]he feedback received from the judges surveyed during this project suggests that there are a potentially large number of prisoners who cannot litigate, with any realistic chance of success, even meritorious claims through certain complex stages of the litigation process, unless they receive at least limited assistance.”50 It is thus no wonder that by 2011, in a survey of chief judges of U.S. district courts, 30.5% claimed that discovery occurred in few or none of their cases involving incarcerated plaintiffs, while 47.5% claimed that it occurred only in the “occasional case.”51 The survey was silent on the quality of discovery occurring for the lucky minority.

Berry’s case provides a glimpse of that lucky minority—an exception that proves the rule. An unusually adept pro se plaintiff, Berry got some discovery. He collected and presented concrete evidence that the prison had tampered with its logbooks—evidence implicating the legitimacy of “hundreds” of prison-litigation cases in Louisiana.52

But his success ended there. The prison had overwritten the surveillance footage of Berry’s incident.53 According to Berry, Sanders intentionally avoided recording body-cam footage of their interaction.54 And though Sanders deposed Berry,55 Berry had no chance to depose Sanders, Parker, other officers, or medical officials to plumb their stories for inconsistencies. Furthermore, even faced with contradictory logbooks, a mixture of security and resource restrictions and a lack of know-how likely kept Berry from pushing further and inquiring into prison policies concerning recordkeeping. Worst of all, the evidence Berry received had largely been curated by the prison: official records parroting Sanders’s account.

Berry’s limited success in uncovering the altered logbook, though astonishing, thus meant little in a system profoundly antithetical to evidence gathering. The rarity of even this limited success lays the problem bare: for every Berry, there are dozens of imprisoned plaintiffs who never make it close to meaningful discovery.56 In turn, abusive prison practices go uncovered and unaddressed, and plaintiffs’ actionable harms go unremedied.

Though some practice guides, court filings, and bar- or court-produced studies bear on the discovery crisis facing prison litigants,57 this is the first law-review article to focus on diagnosing, studying, and addressing it. The Article proceeds in four Parts.

Part I explores the written rules governing prison litigation, including the scant few bearing on discovery. It begins by surveying the impoverished legal options available to those who wish to resist the harsh conditions of their confinement in federal court. The barriers are twofold: many of prison’s indignities simply lie outside the scope of federal causes of action, and for those few who can locate a cognizable claim, the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA)—a 1996 law aimed at stemming frivolous prison litigation—makes its vindication nearly impossible, imposing procedural hurdles at litigation’s earliest phases.58 Most incarcerated plaintiffs’ claims thus fail before discovery even begins. For the few cases that emerge, effective discovery is of vital importance: having survived the PLRA’s hurdles, these are the cases that everyone agrees could well be nonfrivolous—ample reason they be properly evidenced and heard. For these cases, discovery promises fairness, exposure, and regulation sorely needed in the carceral context. But written, prison-specific discovery rules are few, far between, and unhelpful. Part I focuses on the most consequential one: incarcerated plaintiffs are exempted entirely from mandatory initial disclosures, leaving defendants unidentified (and thus dismissed), claims unpursued, and unmoored plaintiffs’ discovery requests overbroad and confused. Local rules impose further limitations that exacerbate these problems.

Part II turns to the unwritten rules that cement discovery’s failures for those plaintiffs who do access the process, relying on case research and dozens of interviews with formerly incarcerated people, federal magistrate and district judges, staff attorneys, civil-rights lawyers, and prison officials.59 This Part begins by outlining the predictable evidentiary needs undergirding most incarcerated plaintiffs’ claims. These needs are not inherently harder to fulfill in the prison context; the problem instead lies in the practical constraints hindering the process. Security concerns make a significant share of relevant evidence simply undiscoverable. And since prisons control the creation and storage of most evidence—surveillance footage, written incident reports, and the like—negligence or ill will can mean the disappearance of (or the failure ever to produce) vital information. Resource restrictions make valuable discovery tools like depositions and expert reports inaccessible to imprisoned litigants, shutting off any real hope of poking holes in a defendant’s story or proving a doctor’s indifference to a medical condition. And hostility between incarcerated people and their jailers breeds distrust, foot-dragging, and credible allegations of spoliation. Together, these difficulties are different in both degree and kind from those faced by other pro se litigants and civil-rights plaintiffs. The Article thus draws the unavoidable conclusion that the aspirationally transsubstantive Federal Rules of Civil Procedure wholly disserve prison litigation. Without unique intervention, no meaningful opportunity exists for incarcerated plaintiffs to evidence their claims. Through this lens, the Article contributes to ongoing efforts to distinguish law in theory from law in practice60 and joins a mounting chorus of scholars critiquing the modes of transsubstantivity propounded in the Federal Rules.61

Part III focuses on two prisons in different federal districts: Angola in the Middle District of Louisiana and Menard Correctional Center in the Southern District of Illinois. In a quasi-empirical, quasi-descriptive study, I scrutinize the dockets and filings in two hundred cases—the first fifty cases from each prison filed in 2016 and 2022—to see whether discovery occurred, and, if so, whether different courts’ approaches to the process made any meaningful difference in the litigation’s prospects or outcomes.

The results are startling. In 2016, plaintiffs’ cases went to discovery in about three-quarters of cases in the Southern District of Illinois but under one-fifth of cases in the Middle District of Louisiana. Plaintiffs settled or won almost half of the cases they brought in the Southern District of Illinois but none in the Middle District of Louisiana. The districts’ differences extend to case-management decisions, with discrepancies in decisions to open or close; when and whether to impose initial-disclosure obligations; how to interact with incarcerated litigants confused by the process; and when and whether to recruit counsel in complex cases. The same trends extended to 2022, with discovery, settlement, and counsel recruitment skewed significantly toward Menard plaintiffs. In illuminating the districts’ differences, Part III draws descriptive accounts from cases forming the basis of the study.

Part IV argues that the discovery problems discussed in Part II, paired with the wildly inconsistent outcomes in the districts surveyed in Part III, together are cause for both pessimism and optimism. First, the lack of standardization and amalgam of restrictions on evidence gathering show a deep and obvious need for reform. It should not be that evidence related to wrongdoing in prison goes discovered or hidden, and a meritorious claim rises or falls, based on the district in which a person does time. Indeed, the results add fodder to scholars’ longstanding observations of randomness and arbitrariness in judicial decision-making—a situation antithetical to our “national desire for equal treatment in adjudication.”62 Nonetheless, the cases from the Southern District of Illinois provide unique insight into a district whose approach and outcomes constitute a profound—and surprisingly positive—outlier in prison litigation. They imply that, even considering the PLRA’s restrictions on prison litigation, there are healthy and effective ways to expand incarcerated plaintiffs’ access to the discovery process.

Part IV ends by suggesting avenues for reform. First, courts should, where resources permit, be far more open to recruiting counsel for imprisoned plaintiffs embarking upon discovery. Second, courts should standardize the discovery process in prison litigation, creating certain tailored discovery rules for imprisoned litigants’ claims. Third, judges should intervene through telephonic status conferences to advise plaintiffs on the process and ensure that they are not floundering or getting the runaround. Fourth, courts should take creative approaches to widening the availability of discovery tools, including making use of new technology to broaden incarcerated litigants’ access to oral depositions. And finally, there should be efforts both in and out of court to police the creation, storage, and disclosure of evidence. This includes spoliation sanctions or curative measures when prisons overwrite surveillance footage after someone has filed a grievance implicating that footage. It also means devising standardized protocols for flagging evidence that poses security risks, along with safe procedures to handle that evidence’s production and use. These admittedly incomplete proposals mark the start of a long-needed confrontation with our prison discovery crisis.

See Answers to Plaintiff’s First Set of Interrogatories to Defendants at 1-4, Berry, No. 17-cv-00318 (M.D. La. June 10, 2019), ECF No. 40 (answering Berry’s interrogatories); Answers to Plaintiff’s Requests for Production of Documents/Records to Defendants, Exhibit 5 at 2-3, Berry, No. 17-cv-00318 (M.D. La. June 10, 2019), ECF No. 39-5 (providing the disciplinary report); Answers to Plaintiff’s Requests for Production of Documents/Records to Defendants, Exhibit 4 at 2-201, Berry, No. 17-cv-00318 (M.D. La. June 10, 2019), ECF No. 39-4 [hereinafter Berry Answer to Production Request, Exhibit 4] (providing medical records); Answers to Plaintiff’s Requests for Production of Documents/Records to Defendants, Exhibit 4 at 2-5, Berry, No. 17-cv-00318 (M.D. La. Mar. 22, 2019), ECF No. 31-4 (providing prison policies regarding security body cameras); Answers to Plaintiff’s Requests for Production of Documents/Records to Defendants, Exhibit 1 at 2-17, Berry, No. 17-cv-00318 (M.D. La. June 10, 2019), ECF No. 39-1 (providing prison policies on the use of force); Notice of Compliance, Attachment at 2-26, Berry, No. 17-cv-00318 (M.D. La. May 13, 2019), ECF No. 37-1 [hereinafter Berry Notice of Compliance, Attachment] (providing logbooks); Order at 1, Berry, No. 17-cv-00318 (M.D. La. Sept. 27, 2019), ECF No. 44 [hereinafter Berry Order] (allowing Sanders’s lawyer to depose Berry).

Answers to Plaintiff’s Requests for Production of Documents/Records to Defendants, Exhibit 1 at 1, Berry, No. 17-cv-00318 (M.D. La. May 17, 2017), ECF No. 31-1 [hereinafter Berry Answers to Plaintiff’s Requests for Production of Documents/Records to Defendants, Exhibit 1]. Though this production was filed earlier in the lawsuit, it was notarized later in time; the other copy had been produced during the prelawsuit grievance process, and, despite its later filing, was notarized at an earlier period of the lawsuit for production as a mandatory initial disclosure. Berry Notice of Compliance, supra note 35, at 1 (listing a certification-of-service date of May 13, 2019); Berry Notice of Compliance, Attachment, supra note 32, at 1 (listing a notarization date of June 15, 2018).

In recent years, scholars have often used the term “prisoner” to refer to people who are presently incarcerated. See, e.g., Justin Driver & Emma Kaufman, The Incoherence of Prison Law, 135 Harv. L. Rev. 515, 525 (2021); Sharon Dolovich, The Coherence of Prison Law, 135 Harv. L. Rev. F. 301, 302 n.2 (2022). I am sympathetic to this choice. As Paul Wright has written, a too-sanitized use of language around prisons can “hide[] the daily brutality and dehumanization of the police state . . . . We should make no mistake about it: people are forced into cages at gun point and kept there upon pain of death should they try to leave. What are they if not prisoners?” Paul Wright, Language Matters: Why We Use the Words We Do, Prison Legal News, Nov. 2021, at 18, 18. Nonetheless, some hear terms like “prisoner” as ignoring the humanity of those navigating carceral contexts. See, e.g., Blair Hickman, Inmate. Prisoner. Other. Discussed., Marshall Project (Apr. 3, 2015, 7:15 AM EDT), https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/04/03/inmate-prisoner-other-discussed [https://perma.cc/8WK6-UDFD]. Additionally, numerous formerly incarcerated people I interviewed for this Article described feeling demeaned or flattened by the word “prisoner,” and encouraged me to use person-first language. Out of respect for them, I try to do so in this piece.

A rich literature demonstrates that the tort system’s information-forcing role is among its primary benefits. See, e.g., Nora Freeman Engstrom, David Freeman Engstrom, Jonah B. Gelbach, Austin Peters & Aaron Schaffer-Neitz, Secrecy by Stipulation, 74 Duke L.J. 99, 161 (2024); Nora Freeman Engstrom & Michael D. Green, Tort Theory and Restatements: Of Immanence and Lizard Lips, 14 J. Tort L. 333, 335 n.5 (2021); Assaf Jacob & Roy Shapira, An Information-Production Theory of Liability Rules, 89 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1113, 1147-48 (2022); Wendy Wagner, When All Else Fails: Regulating Risky Products Through Tort Litigation, 95 Geo. L.J. 693, 696-706 (2007); cf. Shon Hopwood, How Atrocious Prisons Conditions Make Us All Less Safe, Brennan Ctr. for Just. (Aug. 9, 2021), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/how-atrocious-prisons-conditions-make-us-all-less-safe [https://perma.cc/4JWL-D7TZ] (“[T]he worst of prison abuses occur behind closed doors, away from public view.”).

Lynn S. Branham, Am. Bar Ass’n Crim. Just. Section, NCJ 169029, Limiting the Burdens of Pro Se Inmate Litigation: A Technical-Assistance Manual for Courts, Correctional Officials, and Attorneys General 124 (May 1997) (emphasis added), https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/169029NCJRS.pdf [https://perma.cc/X4X6-BQ73]. Of the eight judges who felt that fifty percent or more incarcerated plaintiffs in their district had adequate access to discovery, two said so because they received counsel at the discovery stage in their districts, and two said so because the district effected mandatory disclosures. Id. at 124-25.

Donna Stienstra, Jared Bataillon & Jason A. Cantone, Assistance to Pro Se Litigants in U.S. District Courts: A Report on Surveys of Clerks of Court and Chief Judges, Fed. Jud. Ctr. 22 tbl.18 (2011), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-JU7-PURL-gpo73052/pdf/GOVPUB-JU7-PURL-gpo73052.pdf [https://perma.cc/LU42-2ES5].

See infra Section III.B.2; see also Schlanger, supra note 46, at 1574-76 (discussing the prevalence of federally actionable claims incarcerated people have due to the prison setting); Margo Schlanger & Giovanna Shay, Preserving the Rule of Law in America’s Jails and Prisons: The Case for Amending the Prison Litigation Reform Act, 11 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 139, 140 (2008) (“The PLRA’s obstacles to meritorious lawsuits are undermining the rule of law in our prisons and jails, granting the government near-impunity to violate the rights of prisoners without fear of consequences.”).

See, e.g., John Boston & Daniel E. Manville, Prisoners’ Self-Help Litigation Manual 677-99 (4th ed. 2010); Stienstra et al., supra note 51, at 21-25; Branham, supra note 49, at 124-25; Brief of Former Jailhouse Lawyers as Amici Curiae at 14-22, Herrera v. Cleveland, 8 F.4th 493 (7th Cir. 2021) (No. 20-2076).

Prison Litigation Reform Act of 1995, Pub. L. No. 104-134, sec. 803(d), § 7, 110 Stat. 1321-66, 1321-71 to 1321-73 (1996) (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 1997e). For more on how the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) affects prison litigation, see infra Part I. Though frivolous claims are not uncommon in prison litigation, Margo Schlanger has pointed out that the PLRA’s proponents’ claims of rampant frivolous litigation were simply “not true.” Schlanger, supra note 46, at 1692.

I agreed to keep each interview participant anonymous, unless the interviewee specifically requested to be named. When quoting from an interview, I indicate as much without naming the source. To avoid exposing incarcerated interviewees to retaliation, I spoke only to formerly incarcerated individuals.

For a comprehensive overview of the law-and-society movement, see generally Lawrence M. Friedman, The Law and Society Movement, 38 Stan. L. Rev. 763 (1986), which surveys the movement’s theoretical underpinnings, as well as its benefits and drawbacks; Bryant Garth & Joyce Sterling, From Legal Realism to Law and Society: Reshaping Law for the Last Stages of the Social Activist State, 32 Law & Soc’y Rev. 409 (1998), which surveys the history of the movement; and Austin Sarat, From Movement to Mentality, from Paradigm to Perspective, from Action to Performance: Law and Society at Mid-Life, 39 Law & Soc. Inquiry 217 (2014) (reviewing Kitty Calavita, Invitation to Law & Society: An Introduction to the Study of Real Law (2010)), which documents the institutionalization of the law-and-society movement.

E.g., Joshua M. Koppel, Comment, Tailoring Discovery: Using Nontranssubstantive Rules to Reduce Waste and Abuse, 161 U. Pa. L. Rev. 243, 256-63 (2012) (discussing transsubstantivity’s merits and demerits and arguing for tailored discovery rules); Suzette Malveaux, A Diamond in the Rough: Trans-Substantivity of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and Its Detrimental Impact on Civil Rights, 92 Wash. U. L. Rev. 455, 456-57 (2014) (“The blow that employment discrimination and civil rights claims have taken at the hands of procedural law lays bare any pretense that procedural rules operate in a neutral fashion.”). See generally Stephen N. Subrin, The Limitations of Transsubstantive Procedure: An Essay on Adjusting the “One Size Fits All” Assumption, 87 Denv. U. L. Rev. 377 (2010) (tracing the history of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and weighing their advantages and disadvantages).

Andrew I. Schoenholtz, Jaya Ramji-Nogales & Philio G. Shrag, Refugee Roulette: Disparities in Asylum Adjudication, 60 Stan. L. Rev. 295, 302 (2007); see also Avital Mentovich, J.J. Prescott & Orna Rabinovich-Einy, Are Litigation Outcome Disparities Inevitable? Courts, Technology, and the Future of Impartiality, 71 Ala. L. Rev. 893, 895 (2020) (discussing growing research “cast[ing] significant doubt on the ability of human decision makers to achieve . . . impartiality by uncovering persistent disparities in judicial decisions”); Carlos Berdejó, Criminalizing Race: Racial Disparities in Plea-Bargaining, 59 B.C. L. Rev. 1187, 1189 & n.3 (2018) (discussing judges’ harsher punishments for Black over white defendants).