Pregnancy and Living Wills: A Behavioral Economic Analysis

abstract. “Living wills” are a commonly-used form of advance directive that allow people to state their preferences for medical treatment in the event that they become unable to make those wishes known in the future. But many people, including health-care professionals, are surprised to learn that women in the majority of states are not allowed to have binding living wills during parts of their pregnancies. These so-called “pregnancy exemptions” are likely unconstitutional. They also do a poor job of capturing pregnant women’s true end-of-life preferences. Behavioral economics, the study of how human psychology influences economic decision-making, can help legislators draft living will statutes that more accurately capture women’s preferences and, in the process, provide women with greater individual autonomy.

Introduction

“Living wills” are legal documents that allow people to express their preferences about what medical treatment they wish to receive in the event that they are no longer able to give informed consent. This medical treatment most often comes in the form of CPR, artificial nutrition and hydration, or mechanical ventilatory assistance, but living wills can be written to cover many other interventions as well.1 Although state laws vary on which medical conditions trigger the use of living wills, they are potentially applicable in any situation in which patients cannot communicate their medical preferences, ranging from severe mental deterioration to a persistent vegetative state.2

Since living wills were first proposed in the 1960s, forty-seven states have adopted laws explicitly permitting them, as well as their cousin, health-care powers of attorney.3 Even in the states without specific statutory authorization, living wills are commonly used. While living wills specify in advance particular types of medical treatment that someone does or does not wish to receive, health-care powers of attorney are broader and work by appointing a responsible person as a decision-making proxy. Individuals may choose to draft both documents, since a living will is unlikely to cover all potential circumstances. Advance health-care directives of all kinds are now a mainstay of modern medicine, and studies suggest that about a third of U.S. adults have one in some form.4

Yet many people, including health-care professionals, are unaware that the right to a living will has never been applied equally to all Americans.5 In the majority of states, pregnant women6 do not have the same right to create a living will that refuses medical treatment as people who are not pregnant, and in eleven states, pregnant women are barred by statute from using a living will at all.7 When confronted with a patient who cannot make her own health-care decisions and has no advance directive, courts often use substituted judgment, a standard that asks what treatment the patient would want if she were able to decide for herself.8 One possible justification for excluding pregnant women from using living wills, therefore, may be that the state believes women are unlikely to think about how their preferences might change during pregnancy.9 These statutes are protective of incapacitated pregnant women, so this argument goes, who might be devastated to find out that a doctor was required to “carry out her wishes” to end life-sustaining treatment as directed by a document drafted before she came pregnant, even though she would have preferred to continue treatment and give the fetus a chance to develop.

But the way that many of these state laws are written—invalidating any pregnant woman’s advance directive, regardless of whether the woman explicitly contemplated pregnancy—reveals that accurately capturing a woman’s preferences cannot be legislators’ only concern. From the beginning, limitations on advance directives for pregnant women have been part of the contentious fight around the ethics of abortion. To gain support for advance directive laws, state legislatures in the 1980s added pregnancy exemptions to sidestep the abortion debate10 and “ease the qualms of the Roman Catholic Church and others.”11This was a victory for pro-life advocates, who understood requiring a doctor to give medical treatment to an incapacitated pregnant woman to protect her fetus as a logical next step in protecting human life. It did nothing to address the concerns of pro-choice advocates, however, who viewed forcing medical care on unwilling pregnant women as a dramatic violation of women’s autonomy.

Today, pregnancy exemptions are a relatively obscure issue, but that’s beginning to change. A 2014 case, in which a pregnant Texas woman named Marlise Muñ0z was forced against her family’s wishes to remain on life support machines for more than two months after she was declared brain dead, drew national attention.12 In addition, the confirmation of Justice Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court has increased the urgency with which reproductive justice advocates are pushing for legislative reforms. In many states, pro-choice advocates are urging legislatures to pass abortion protections in the event that Roe v. Wade is overturned.13 In more liberal states that already have laws legalizing abortion, advocates are looking to reforms that were historically lower-priority,14 including pregnancy exemptions in advance-directive statutes.15 These laws are also good targets for reform because there are strong arguments that they are unconstitutional. Especially in their strictest form, pregnancy exemptions impermissibly restrict pregnant women’s right to refuse unwanted medical care and infringe on their right to abortion. Since pregnancy exemptions were enacted in the 1980s, pro-choice advocacy groups have successfully lobbied several states to repeal them, most recently in Connecticut, which amended its advance-directive statute in May 2018.16

As advocacy groups and the legislators they lobby begin working to revise states’ advance-directive laws, they should consider insights from the field of behavioral economics regarding how such a law might most effectively capture people’s health-care preferences, including the preferences of women who are pregnant or may become pregnant. Doing so would help them honor the values of autonomy and dignity that animated the creation of living wills to begin with and would help address potential criticism that women fail to accurately predict the impact pregnancy would have on their health-care choices. It is an increasingly common practice for scholars and practitioners to apply behavioral economics—the study of how human psychology influences economic decision-making—to complicated legal and regulatory problems like this one.17 While behavioral economics cannot definitively answer complicated ethical questions like “when does life begin?,” this approach can help policymakers understand how patients’ preferences, including significant ones like whether to reject medical intervention, are influenced by seemingly unimportant factors in the patients’ environment. Behavioral economists’ key insight is that people are not purely rational actors with fixed preferences. Instead, we have cognitive biases that affect the way we make decisions—sometimes dramatically. Legislators in all states should be concerned about state laws that inadvertently distort women’s decisions, just as they should be about laws that deny women the opportunity to make a decision at all.

To explore what behavioral economics can contribute to the debate about pregnancy exemptions in living-will statutes, this Essay provides a brief introduction to the history of living wills in health care, surveys how the laws apply to pregnant women, explains why pregnancy exemptions to living will statutes are likely unconstitutional, and then analyzes advance-directive laws according to behavioral economics principles. It ultimately offers suggestions for how states—both states with unconstitutional pregnancy exemptions and those without—should revise their laws. Although other scholars have analyzed how states’ advance-directive statutes exclude pregnant women, they have primarily done so through a constitutional lens.18 This Essay instead uses behavioral economics to suggest how states can most effectively reform pregnancy exemptions in advance-directive laws so as to best respect the wishes of pregnant women.

I. the history of advance directives in health care

Luis Kutner, a notable human rights attorney, is often credited with first proposing the concept of a living will in a 1969 article.19 His concept spread quickly. Seven years later, California became the first state in the country to pass a bill permitting living wills.20 In 1990, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health, the first so-called right-to-die case.21 The decision recognized that individuals have a right to create binding living wills and brought unprecedented public attention to advance directives.22 Two years later, all fifty states had statutes permitting the use of some form of advance directive.23

Living wills are a form of advance health-care directive. They specify what kind of medical treatment a person would want if she is someday no longer able to give informed consent. Under almost all states’ laws, individuals additionally have the option to name a health-care power of attorney, which gives a friend or family member the authority to make health-care decisions not covered by a living will.24 These documents are classified differently from state to state, but they all pursue the same goal: ensuring that incompetent individuals are given only the medical treatment that they would have consented to if they were still able to make decisions on their own.25

In general, if someone is no longer able to give consent to medical care, doctors default to providing life-sustaining treatment.26 The law will eventually turn to relatives, close friends, or even a representative appointed by the state to make health-care decisions for the patient,27 but in the interim, it is common practice for doctors to take dramatic life-saving steps like performing CPR, even if the doctor believes this is ultimately futile.28 In many cases, the patient does not prefer such aggressive treatment. People might decline certain medical interventions for cultural or religious reasons,29 or because they worry about the pain and psychological stress of intrusive and long-lasting medical treatment.30 Others are concerned with the financial burden that excess health care will put on their families after they die, or are worried about the psychological burden they could put on their loved ones if their relatives are forced to make these important choices for them.31 Advance directives are useful in ensuring that these wishes are carried out with the least possible conflict and legal risk. Both families and medical providers want to avoid going to court to litigate end-of-life care decisions, and doctors want to ensure that they will be protected from civil or criminal liability if they forgo certain medical procedures.32 Living wills provide a measure of certainty as to what the patient herself wanted, easing what can otherwise be an impossibly difficult decision to decline potentially life-extending interventions.

A large majority of Americans support laws that give patients the ability to decline medical treatment, even if doing so would lead to the patient’s death.33 But despite its current popularity, the idea for advance directives was initially controversial. Proponents saw living wills and other advance directives as important expressions of individual autonomy.34 For them, living wills were a natural and beneficial outgrowth of a broader shift within the medical community away from paternalism and towards allowing patients to actively participate in their own treatment.35 Patients’ ability to control their end-of-life health care was eventually reframed by activists as a “right to die.”36 Opponents of the movement viewed the “right to die” as nothing more than suicide by a nicer name.37 Some doctors believed that facilitating a patient’s request to refuse life-sustaining medical treatment would be a violation of their fundamental ethical duties.38

Ultimately, courts tasked with deciding this issue came down in favor of a patient’s right to refuse medical treatment in two important cases. In a highly influential 1976 decision, the New Jersey Supreme Court established the right for patients to create a health-care power of attorney in a case called In re Quinlan.39 In 1990, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health that individuals have the right to create a binding living will.40 Congress has also stepped in to defend an individual’s right to control her own end-of-life care. Under the Patient Self-Determination Act of 1991, many health-care providers who accept Medicare or Medicaid must inform all adult patients in writing of their right to prepare an advance directive.41 Today, living wills are an accepted part of end-of-life care, and the debate about living wills is primarily about whether they produce measurable increases in quality of death and how their implementation can be improved.42

II. living wills’ application to pregnant women

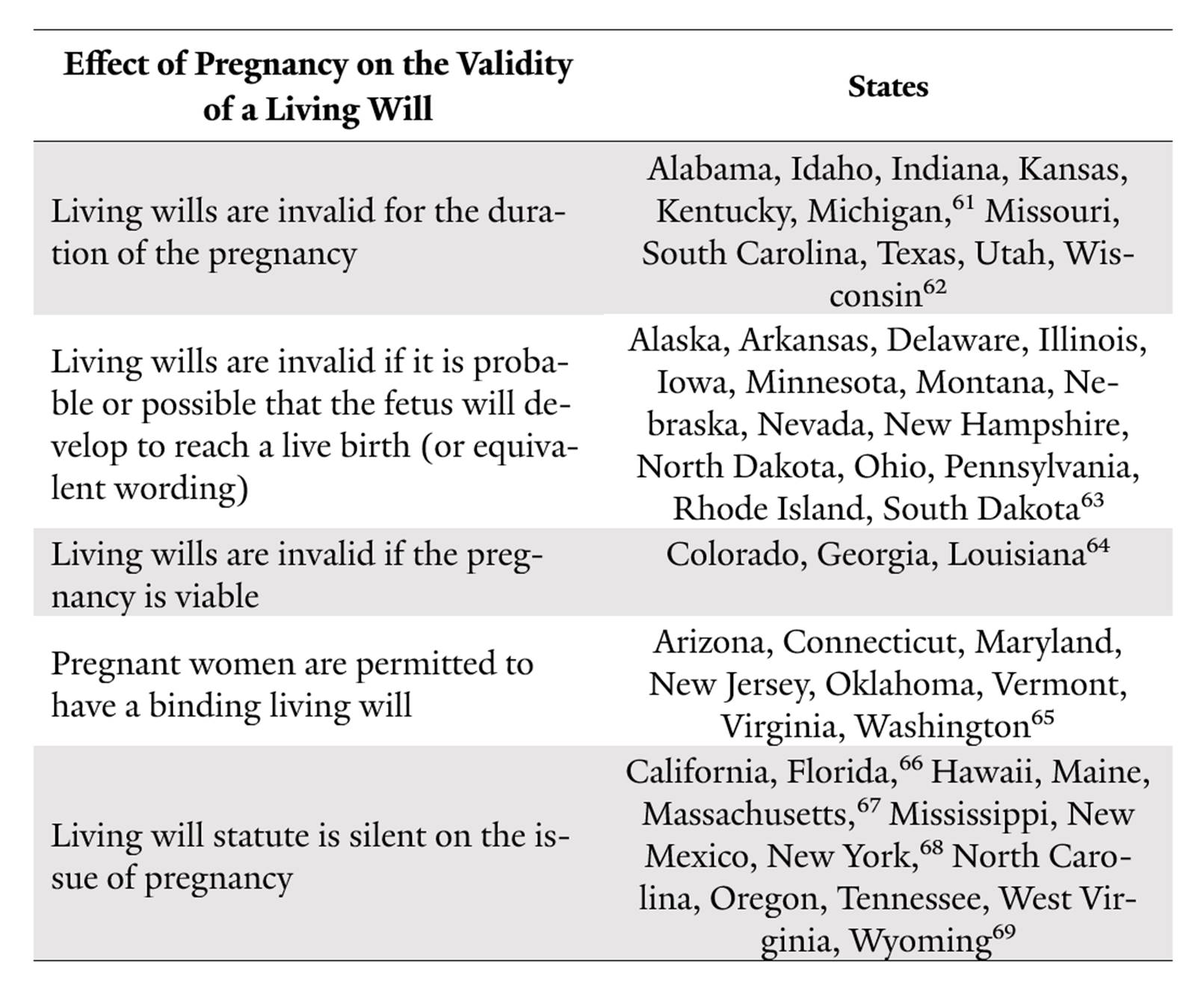

Even though the use of living wills is now relatively uncontroversial, certain populations remain barred from using them in all instances. Laws in eleven states automatically invalidate a woman’s living will for the period in which she is pregnant.43 The laws are indifferent to whether the living will was created prior to or during a pregnancy, or whether the will specifically contemplates the possibility that the writer may become pregnant. Given the American medical profession’s tendency to default to aggressive treatment, a pregnant woman in one of these states who becomes incapacitated and dependent on medical intervention is very likely to remain on life support until she dies,44 the fetus dies, or she gives birth.

The fact that they are pregnant, however, would not necessarily convince women who would be inclined to reject aggressive end-of-life medical care to accept it, and a pregnancy may make some women less likely to accept such care. Often, the accident or illness that caused the woman to be incapacitated also affects the health and survival rate of her fetus, so continuing the pregnancy may be futile.45 This potentially unnecessary treatment can be extremely expensive, and depending on the hospital’s policies and the patient’s insurance, some of the cost could fall to the surviving family members.46 In addition, just the act of keeping a woman on life support can be dangerous for the fetus: ventilators and catheters are “major sources of infection” that can harm a fetus’s development.47 Finally, the pregnant woman may not get optimal care if her doctors have to balance her interests against those of a more fragile fetus.48 Despite these concerns, laws in these eleven states do not make any allowances for the woman’s pain, the development of the fetus, or the fetus’s prognosis.49

In fifteen other states, advance directives are not automatically invalidated for the entire pregnancy, but they become invalid if it is “probable” or “possible” that the fetus will develop for a “live birth.”50 In addition, Colorado, Georgia, and Louisiana give no effect to a woman’s advance directive if her fetus is “viable.”51Both standards are vague and hard to apply. It is often difficult to determine if a pregnancy will develop to a live birth since these cases are rare and the prognosis of many of these fetuses is poor or unknown. Similarly, there is no hard line separating viable from nonviable pregnancies.52 In the years between Roe v. Wade in 1973 and Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992, improvements in medical science pushed back the point of viability in most pregnancies by several weeks, making it clear that “viability” is an ever-changing standard that is heavily dependent on technological advancement.53

The evidence is anecdotal, but hospitals appear to approach these partial-exemption laws conservatively and tend to err on the side of keeping pregnant women on potentially unwanted medical support. In a 2017 article, for example, doctors in Pennsylvania reported that they overrode a family’s request to withdraw life support from a pregnant woman in a persistent vegetative state, in part because they felt bound by state law.54 Although some of the women’s doctors “were initially uncomfortable with the decision,” the hospital believed that “care options were limited to supporting the pregnancy.”55

Only eight states—Arizona, Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, Oklahoma, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington—permit pregnant women to make binding living wills.56 The remaining thirteen states are silent about the issue,57 meaning that cases from these states are more likely to end up in court, prolonging potentially unwanted medical care for the pregnant woman.58

Without definitive interpretations by the courts, even these broad categories—complete pregnancy exemption, partial pregnancy exemption, no exemption, silent on the issue—are approximate. For example, some states provide a model form containing a pregnancy exemption and require that advance directives be “substantially the same” as the model form to be binding. Depending on that phrase’s interpretation, these laws could be understood as either requiring all living wills to contain a pregnancy exemption or explicitly permitting pregnant women to override the exemption. Again, ambiguity in the law will tend to lead towards more litigation and delay for pregnant women and their families if they seek to reject additional medical care.

Further, it is not just living wills that are out of reach for many pregnant women. In many states, women who are pregnant are forbidden from writing a binding health-care power of attorney—a document that allows someone else, like a spouse or a friend, to make health-care decisions for the woman if she is incapable of doing so.59 In states without power of attorney restrictions but with living will restrictions, pregnant women may still be effectively prohibited from appointing someone else to withdraw care, because states usually do not allow proxies to make medical choices that patients cannot make on their own.60

table 1. state treatment of pregnancy and living wills616263646566676869

|

In the United States, living wills have always been more controversial in the context of younger rather than older people. It is not a coincidence that the three most controversial “right to die” cases—In re Quinlan,74 Cruzan,75 and the Terri Schiavo case—all involved young women in their twenties who suffered from sudden medical trauma. The Terri Schiavo controversy centered around a woman who, at twenty-six years old, was put into a persistent vegetative state following a heart attack. Eight years later, her husband attempted to take Schiavo off life support, a move that her parents vigorously opposed. The case caused such public outcry that the Florida governor,76 the U.S. Congress,77 and the Pope78 all tried to intervene. Young women who wish to refuse life-sustaining treatment when they are pregnant—because of the implications their actions have for the debate over abortion—are bound to cause even more controversy.79

That dynamic is illustrated in the case of Marlise Muñoz, a thirty-three-year-old Texas woman who suddenly collapsed in the kitchen on her way to prepare a bottle for her son.80 She was fourteen weeks pregnant at the time, and the hospital eventually declared her brain dead. Technically, Texas’s Advance Directives Act only covers patients who are alive but cannot communicate to give informed consent.81 It does not cover brain-dead people, who are not legally or clinically alive.82 It also only covers people who have advance directives; Muñoz did not.83 Nevertheless, the hospital relied on the law as evidence of legislative intent to keep Muñoz’s body on a ventilator until her fetus was delivered or died.84 It disregarded statements from Muñoz’s husband and parents claiming that, as a paramedic herself, Muñoz knew with confidence that she would not want to be artificially kept alive by machines.85 A state district judge ultimately ruled against the hospital and ordered it to remove Muñoz from life-support machines, but not until more than two months had elapsed since she was declared brain dead.86

When situated within the national debate over abortion, it seems unsurprising that states have adopted such restrictive regulations of pregnant women and living wills. But taken in another light, this legal heterogeneity is puzzling. Women have the right to an abortion.87 Women also have the right to refuse medical care.88 So why, in ten states, are women prohibited from prospectively declining medical care if it might cause the death of a fetus?

III. the constitutionality of pregnancy exemptions

How states should balance their interest in human life with individuals’ right to bodily autonomy is the legal and ethical question central to the national abortion debate. But when legislators balance these interests differently than the Supreme Court did in cases like Roe v. Wade89and Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey,90 they risk violating women’s constitutional rights. Numerous commentators believe that pregnancy exemptions are unconstitutional, both because they represent an undue burden on a woman’s right to have an abortion before viability of the fetus and because the government’s interest in the potential life of the fetus cannot override a woman’s right to refuse medical care.91

Since the 1960s, the Supreme Court has recognized that the state may not interfere with an individual’s right to make private reproductive health decisions. In Griswold v. Connecticut, the Court established the right for married couples to use contraceptives without government interference.92 In Eisenstadt v. Baird, the Court extended that privacy right to unmarried individuals,93 and in Roe v. Wade, applied it to abortion.94 In Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the Court reaffirmed that women have the right to terminate a pregnancy previability, but also acknowledged the state’s interest in potential life and allowed the state to impose restrictions on a woman’s right to choose as long as the restrictions do not place an “undue burden” on the woman.95

Do pregnancy exemptions from state living-will statutes represent an undue burden on women’s right to abortion? Although the courts have yet to rule on the issue, the answer appears to be yes.96 In Gonzalez v. Carhart, the Supreme Court allowed Congress to ban the intact dilation and extraction method of abortion, or so-called “partial-birth abortion.”97 But it did so, in part, because it determined that the method would never be medically necessary for women, because women have other methods of abortion available to them.98 The Supreme Court has never blocked an entire group of women from accessing abortion pre-viability, as eleven states do by prohibiting pregnant women from using living wills altogether, whether or not they are carrying a viable fetus. These states appear to be acting unconstitutionally. Although more likely permissible, the fifteen states that force women to accept unwanted medical care if it is “possible” or “probable” the fetus will develop to have a “live birth” may also be violating the Constitution. The “probability of a live birth” standard is so vague and medically uncertain that it could easily encompass any pregnancy and could also represent an undue burden on the rights of women to terminate a pregnancy pre-viability.99

In addition, in a separate line of cases, the courts have recognized individuals’ right to refuse unwanted medical procedures. In the influential case In re Quinlan, the New Jersey Supreme Court found that individuals’ right to privacy encompasses declining unwanted medical care, much as individuals’ right to privacy protects their right to an abortion.100 The court then weighed this privacy right against the state’s interest in preserving human life, and found the state could not force unwanted medical care on people who have expressed their wishes to others through a health-care power of attorney.101 Similarly, in Cruzan, the U.S. Supreme Court found that the Due Process Clause protects an interest in refusing life-sustaining treatment and that people may express their health-care preferences in advance through living wills.102

The Supreme Court has never ruled on precisely when the state’s interest in human life outweighs a person’s right to refuse unwanted medical care. Theoretically, the state’s interest may never be strong enough to justify violating a woman’s bodily autonomy, regardless of how far along she is in a pregnancy. After all, the state cannot, for example, force someone to donate her kidney, even if it would prevent another person from dying.103 In at least thirty instances, however, courts have forced women to undergo Cesarean-sections or other medical procedures to protect the health or life of a fetus over the objections of the pregnant woman.104 Cases reviewed on appeal are usually decided in favor of the woman, but for various reasons, including the unwillingness of new parents to pursue litigation and the low potential for damages, few cases are ever appealed.105

Under both theories, then—a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy pre-viability without undue interference and a woman’s right to decline unwanted medical treatment—pregnancy exemptions from living-will statutes are likely unconstitutional. Full bans are almost certainly unconstitutional under both theories, and bans pegged to “viability” or the “potential” for life may be unconstitutional as well under the line of cases that protect people’s right to decline medical treatment. So far, however, judges have not considered the constitutionality of these laws directly. Courts in both Washington and North Dakota declined to hear challenges to pregnancy exemptions on the grounds that the cases were non-justiciable because the women suing were not currently pregnant or incapacitated, so their harm was too abstract.106 A similar provision in Idaho is currently being challenged, but the court has yet to reach a decision in the case.107

Advocates are challenging pregnancy exemptions directly in the legislature as well, with some success. Washington State repealed its exemption in 1992108 and Connecticut followed suit in 2018.109 But as advocates push to repeal states’ pregnancy exemptions, they should be wary of competing efforts to expand them. In 2014, for example, in the wake of the Marlise Muñoz case, one Texas legislator proposed eliminating the pregnancy exemption, but another legislator proposed strengthening it to clarify, somewhat paradoxically, that the prohibition on pregnant women declining “life-sustaining treatment” could apply to pregnant women who are already brain dead.110

IV. behavioral economics and living wills

As legislators consider possible revisions to their advance-directive laws, either to bring them into constitutional compliance or to make them more respectful of individual autonomy, they should incorporate lessons from behavioral economics to ensure that they are drafting laws that will accurately capture people’s true preferences. Behavioral economics can offer fresh insights to policy makers facing complicated legal and regulatory problems like the application of living wills to pregnant women.111 Unlike traditional economics, which has long found a home in the world of law and policy, behavioral economics is a relatively new analytical tool, but it has quickly gained a following.112 Behavioral economics challenges one of economics’ core assumptions: that humans are purely rational actors who will always act in their own best interests.113 Instead, behavioral economists believe that humans have cognitive biases that lead them to make apparently “irrational” decisions, although often in predictable ways.114 This is especially true for decisions that involve “uncertainty, emotion, and complex trade-offs between current and future costs and benefits.”115 Such decisions are common in health care, prompting health professionals to turn to behavioral economists to help answer questions such as why people fail to exercise when the benefits are so well documented and why people skip medication even when it could improve their quality of life.116

Behavioral economics cannot solve the difficult ethical and constitutional problems in end-of-life care, like balancing individual autonomy against the potential for life. But it can help describe the forces that are already affecting people’s end-of-life decisions, and it can suggest how policymakers may manipulate these forces to either facilitate people achieving their “true preferences”—to the extent they have them—or nudge people towards a specific policy objective. It can also help advocates and legislators stay alert to the possibility that the language in a living will statute might influence women, causing them to opt for aggressive life-sustaining treatment in situations where they might actually prefer to withdraw treatment, even if that means terminating their pregnancies. This sort of pro-intervention language in living-will statutes reflects a set of values that prioritizes any sacrifice that will allow the fetus to continue to gestate, an approach that harmonizes with many pro-life goals. They can also be alert for the reverse—language that encourages more women to withdraw care than otherwise would, which reflects a stronger emphasis on women’s autonomy and the right to choose and echoes the goals of the pro-choice movement.

Much of the early work behavioral economists have done on the subject of living wills focused on how to increase their use in the general population. Although the leading organizations working on end-of-life care suggest that all adults should have an advance directive,117 only about a third do, including only about sixty percent of patients in hospice or palliative care.118 Behavioral economists have identified several cognitive biases that contribute to the low uptake of advance directives.

One such bias is that people tend to be overly optimistic about the chance that they will never need an advance directive.119 They either believe that they will never become incapacitated or they believe that their relatives know their preferences more accurately than they actually do.120 Behavioral economists identify this behavior as an expression of “optimism bias,” the irrational belief people have that they are less likely to experience a negative event than others.121 Doctors can similarly suffer from optimism bias. They tend to believe that their patients are more likely to recover than they statistically are and so fail to bring up advance directives even in cases where the patient could have benefited from one.122

Another bias affecting patients’ use of living wills is “present bias.” Behavioral economists define present bias as people’s tendency to overvalue positive things in the short term as compared to potential long-term gains.123 Even though the potential benefits of completing an advance directive are great, many people will still avoid them because they overvalue the happiness they will get in the present from avoiding an unpleasant task that involves thinking about their own mortality.124

Behavioral economists who study these biases suggest that doctors can increase their patients’ use of advance directives if they focus on providing information that is likely to be persuasive enough to overcome present bias. In particular, they recommend that doctors discuss with patients how their relatives may be burdened if they have to make medical decisions for the patient without written guidance.125

Behavioral economists also have challenged the basic assumption that most people’s end-of-life preferences are held strongly enough to withstand the influence of seemingly minor factors like the way a question is presented. In one study, researchers divided patients into three groups, where each group was given a different advance-directive form to help them express their end-of-life instructions. One group’s form had a default option preselected that instructed future medical professionals to prioritize the patient’s comfort. Patients were free to select a more aggressive treatment plan; they just had to cross out the first option. Members of the second group were given a similar form where the default option was to extend life, even if it caused pain and suffering, and the third group had no default option at all. The default that each group was given had a significant effect. When the participant was required to make an affirmative choice, sixty-one percent chose comfort as the overall goal of their care. When patients were given forms with life-extending options preselected, only forty-three percent overrode the default to select comfort-oriented care. Of the group with comfort options preselected, seventy-seven percent retained that goal.126

“Rational” actors would not base their decision about something as important as end-of-life care on something as trivial as a pre-selected default on a form. Behavioral economists, however, have done extensive work on the power of default options to sway decision-making in many different contexts. When people must “opt out” instead of “opt in,” studies suggest that they are more likely to donate their organs,127 get prenatal screening for HIV,128 and contribute to their 401(k) retirement savings accounts.129 There are several reasons why individuals become so attached to the default option. People tend to interpret defaults as the social norms, which could subject people who break them to social confusion or ridicule. Even more subtly, many people suffer from “loss aversion,” meaning they feel more strongly about losing a benefit than they do about gaining a benefit of the same magnitude.130 Loss aversion can apply to even something as fleeting as the default option they were first presented with, meaning that patients in the first group of the advance directive study described above may have become attached to the idea of receiving “comfort-based” treatment and felt a distinct sense of loss when they had to actively select the aggressive treatment instead. Other studies suggest that even the order that options are presented in a list can affect which choices people make, even without any option designated as the default.131

Framing effects, even subtle ones, can have similarly significant effects on people’s end-of-life decisions. In one study, researchers offered subjects possible medical interventions, phrasing the intervention in negative terms for one group (i.e., which treatments should be withheld) and in positive terms for another (i.e., which treatments should be administered). Thirty-eight percent of the study participants opted for an intervention when it was described as potentially being withheld, while only twenty percent opted for it when described as a treatment that could be administered.132 Other researchers have found an effect on end-of-life preferences based on “whether success or failure rates are used, the level of detail employed, and whether long- or short-term consequences are explained first.”133

In combination, a doctor’s several idiosyncratic methods of conveying information—phrasing questions in positive instead of negative terms, for example, or listing certain facts first—can end up having powerful effects on the patients’ stated preferences. In one study, patients in the same ICU had an otherwise unexplained fifteen-fold variation in the rate that they chose to forgo life-sustaining therapies under the care of nine different doctors.134

Legislators from any state should keep these biases in mind when drafting revisions to their living will laws. Even small changes in language could end up having a large effect on what pregnant women state are their health-care preferences. Many states include sample advance-directive templates in the text of their laws, but even for those that do not, agencies, lawyers, and others are likely to hew closely to the legislative text for guidance to make sure that the advance-directive templates they suggest to individuals meet the state requirements.135 Behavioral economics suggests that living will templates will solicit more accurate and unbiased responses if they are drafted with neutral language.136 Similarly, no model form should have a preselected default.137 As behavioral economists and psychologists identify additional cognitive biases and ways to combat them, policymakers should work to refine their living will statutes to ensure that they lead to documents that most accurately reflect the patient’s own desires.

Unfortunately, not all states that have amended their laws follow the guidance above. Washington State, for example, repealed its pregnancy exemption in 1992,138 so it no longer automatically invalidates women’s living wills during their pregnancies. It did so, however, by merely replacing the phrase “[t]he directive shall be essentially in the following form” with “[t]he directive may be in the following form.”139 Therefore, Washington still has a form with the default option to invalidate women’s living wills during pregnancy.140 While women in the state are free to modify their living wills however they please, behavioral economics tells us that they are significantly more likely to keep the default than to change it.

A better model is Connecticut, which also recently revised its laws that previously prohibited women in the state from having living wills while pregnant. Instead of the state selecting a default course of action and allowing the woman to override it, Connecticut’s new model form asks women to make an active choice between applying their living will without modifications during pregnancy, accepting additional medical intervention, or something else that they specify.141 At least theoretically, requiring women to make active choices instead of relying on a default makes them more likely to identify their true preferences.

The field of behavioral economics is sometimes criticized for being coercive, because it allows government officials to nudge people towards different behavior without the people ever realizing they were being manipulated.142 But at its best, behavioral economics is actually liberty-enhancing, because it helps policymakers understand and remove the environmental factors that were already pushing people towards one option over another, just in an unintentional and haphazard way. Recognizing and removing these barriers is important for protecting women’s autonomy. Most women, if they were to ever become incapacitated while pregnant, would presumably want to make a decision as sensitive as what medical care they wish to receive with minimal coercion from the state.

Legislators in states with unconstitutional pregnancy exemptions—particularly states that exclude all pregnant women from using advance directives—should amend their laws to bring them into constitutional compliance. If their legal challenge is successful, advocacy groups may soon force Idaho to do so, and other states would likely follow.143 But even outside of the constitutional issue, legislators should eliminate pregnancy exemptions because behavioral economics tells us that they do an exceptionally poor job of capturing pregnant women’s true preferences for their end-of-life medical care. Pregnancy exemptions are innately coercive because they overestimate the likelihood that pregnancy will change a woman’s health-care preferences towards more treatment. Although pregnancy is undoubtedly a significant event in the lives of many people, there is no compelling reason to suggest it is uniquely significant, over and above the effect on preferences that, for example, the death of a loved one or a religious conversation might have. More importantly, just because a particular woman may inaccurately predict what her end-of-life preferences would be before and after pregnancy, there is no guarantee that all women will always be inaccurate in the same direction. It is certainly plausible that a woman would choose to undergo expensive and painful treatments in the hopes of giving a fetus a chance at developing. But it is also plausible that a woman, if pregnant, would choose less medical intervention. Perhaps she would worry about causing pain and suffering to her fetus, knowing that it has only a small chance of surviving until birth. Perhaps she would be worried about leaving a disabled infant in the hands of a child welfare agency. Some women who are pregnant for the first time may change their views during the pregnancy and desire additional care in the event that they become incapacitated, but many pregnant women have been pregnant before. These women presumably would have already adjusted their preferences if they were going to change. In that sense, these laws are, at best, over-inclusive.

Legislators from states that currently have full bans on pregnant women using living wills may look to a partial ban as a reasonable compromise that could pass constitutional muster. In partial ban states, pregnant women may be forced to submit to potentially unwanted medical care if it is either “probable” that the pregnancy will develop to a “live birth” or if the fetus is “viable.” At first glance, these laws may seem more moderate because they allow women’s right to bodily autonomy to override the state’s interest in potential life at least part of the time. However, partial bans resolve almost none of the issues identified with complete bans in capturing women’s true preferences regarding her medical care when pregnant. A viability standard still does not account for the prognosis of the women or fetus, does not consider the likelihood that the woman considered pregnancy while drafting her advance directive, and inappropriately singles out pregnancy as a life event uniquely likely to change someone’s preferences.

A better option for states looking to revise their advance directive laws to make them constitutional would be to eliminate pregnancy exemptions altogether. State model forms could still ask women about whether their preferences would change during pregnancy without forcing a specific answer. In addition, states could require explicit conversations between doctors and pregnant women on the subject. States without pregnancy exemptions should consider this option as well, in addition to reforming the language of their laws to account for the behavioral economic insights identified earlier. The federal Patient Self Determination Act (PSDA) already requires health-care providers to notify patients of their right to create advance directives at several other points, and it could easily be amended to include the first prenatal visit. A report by the Government Accountability Office, published five years after the PSDA was passed, found that institutional providers were largely complying with the law’s requirements, a fact that suggests that obstetricians would also tend to follow this requirement.144 If the U.S. Congress does not act, states could add this requirement independently.

This proposal still singles pregnancy out among other significant life events. In addition, simply asking the question may be read by some women as the state suggesting that revision is necessary. Nevertheless, at a minimum, this policy preserves choice while also prompting women who may not have thought about the possibility that they could become incapacitated while pregnant to ensure that their wishes remain unchanged. It also has the benefit of encouraging more people to create advance directives, and this encouragement may promote better uptake rates than normal since pregnancy is traditionally a time when people reflect on their values and plan for the future.

Some pro-life legislators may feel that they can never support revisions to their states’ advance directive laws that would allow pregnant women to decline life-sustaining medical treatment. For them, the state’s interest in potential human life should, at least sometimes, outweigh women’s ability to direct their own health-care decisions. But if such legislators find themselves outvoted or pregnancy exemptions are found unconstitutional, they too may find themselves trying to revise these laws. In that case, they should also support requiring doctors to bring up advance directives during a pregnant woman’s first prenatal visit and other behavioral economics-inspired reforms. This will, at a minimum, reduce the risk that women will accidentally decline care that they would have wanted if they had accounted for the possibility that they would become incapacitated while pregnant.

Conclusion

Stories like the Marlise Muñoz case and increased fears stemming from President Trump’s new nominations to the Supreme Court have brought more attention to reproductive justice issues, including pregnancy exemptions. These exemptions are prime candidates for legislative lobbying efforts, because they are likely unconstitutional and do a poor job of accurately capturing pregnant women’s preferences around end-of-life care for themselves and their fetus. As legislators look to revise their states’ advance directive laws, they should consider what behavioral economics suggests about how best to respect women’s right to make their own medical decisions. Using neutral language and eschewing pre-selected defaults will help states avoid unintentionally manipulating the preferences of women who may become pregnant. Requiring doctors to inform pregnant women of their right to create or amend an advance directive at their first prenatal visit would also ensure that women’s preferences account for the impact of their pregnancies. Making these reforms would minimize the coercive power of the state and would provide pregnant women with greater autonomy in this private and important context.

Elizabeth Villarreal is a J.D. candidate at Yale Law School. Thank you to Christine Jolls and Matthew Lifson for inspiring this Essay and giving helpful comments, and to Chris Zheng and Brendan Costello for their suggestions. Thank you also to Alaa Chaker, Alexandra Lichtenstein, and other editors of the Yale Law Journal.