Special Juries in the Supreme Court

abstract.The Seventh Amendment mandates juries in federal courts for cases that would have required them at common law. Yet the nation’s highest federal court has presided over a jury trial in only one reported case, Georgia v. Brailsford (1794). The prospect of a jury trial in the Supreme Court makes the case intriguing enough. Brailsford, however, is even more well-known for its provocative language on the jury’s power to decide the law as well as the facts. Nevertheless, the trial remains largely unstudied. This Note examines the case’s extant documents and argues that the jury the Supreme Court used was a special jury of merchants in the tradition of Lord Mansfield. This conclusion offers insights into how the Supreme Court might negotiate a jury trial in a future case if the Seventh Amendment should demand it. Further, this Note’s finding provides a context to understand better Chief Justice Jay’s words on the jury’s authority to determine the law as well as the facts.

Yale Law School, J.D. 2013; Johns Hopkins University, Ph.D. 2010; New York University, B.A. 2005. I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to Akhil Amar for inspiring and supervising this Note, to John Langbein for his meticulous help and encouragement, and to Maeva Marcus and James Oldham, both for their assistance and for their remarkable publications, without which I could never have written this Note. Many thanks also to Ida Araya-Brumskine, Christian Burset, and Andrew Tutt for their insightful comments and debates.Any errors are, of course, my own.

Introduction

In Suits at common law . . . the right of trial by jury shall be preserved . . . .1

The Seventh Amendment requires juries in federal common law suits that historically would have used juries.2 Yet, one federal court has not sat with a jury for over two centuries: the Supreme Court of the United States.

This was not always the case. In its first decade of existence, the Supreme Court impanelled juries as a matter of course at the beginning of every Term. The Court heard at least three cases with juries in the 1790s, only one of which was reported: Georgia v. Brailsford.3

Brailsford pitted Georgia against a British creditor. Each claimed the right to collect a debt from a Georgia citizen. Because a state was a party, the case fell within the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction. Moreover, because Brailsford was a common law action, the Supreme Court impanelled a jury; in this case a “special jury.”

Brailsfordhas continued to pique interest over the past two centuries. First, the case presents the intriguing prospect of the Supreme Court presiding over a jury trial. Second, the case contains provocative language regarding the power of juries to decide the law as well as the facts. Despite this interest, however, the case’s details have not been much studied, and its contemporary significance remains obscure. Scholars have lamented that “the published court records provide no clues as to the jury’s composition or how it was selected.”4 There are, however, several extant documents that have not previously been explored.

This Note analyzes these documents from the Supreme Court’s only published jury trial. It examines forty individuals named in the case’s hitherto unstudied venire facias, or list of potential jurors, and shows that ninety-five percent of the potential jurors were merchants. It then analyzes the extant notes from the oral argument of Brailsford’s attorney, and shows that the defense made extensive reference to the law merchant, a body of internationally-derived mercantile customs and practices. This Note concludes from these and other pieces of evidence that the “special jury” the Court employed was a jury of merchants in the tradition of Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of King’s Bench from 1756 to 1788.Lord Mansfield commonly used special juries of merchants to determine mercantile custom and to help incorporate it into the common law.

Brailsford is the only published case in which the Supreme Court has presided over a jury trial. Today, it would seem incongruous for this multi-member court, which is almost exclusively focused on appellate matters, to oversee a jury trial. The overwhelming majority of cases that the Supreme Court does hear in its original jurisdiction are equitable in nature and therefore do not require a jury. Instead, the Court delegates any fact-finding to a special master. Scholars have called the prospect of a jury trial before the Supreme Court “appalling” and “to be avoided at all costs.”5 Nevertheless, the Seventh Amendment mandates the Supreme Court to impanel a jury in cases that traditionally would have used one. This Note’s conclusion that the Supreme Court used a special jury of merchants thus offers a possible way to reconcile constitutional mandate with seemingly impractical procedure. An expert jury on a particularly complex and sensitive issue would be both consistent with historical practice and feasible for the Court if it were to hear another case that mandated a jury trial.

Scholars also often discuss Chief Justice John Jay’s statement in Brailsford regarding the power of juries to find the law as well as the facts. In the only published jury charge that the Supreme Court ever delivered, Chief Justice Jay uttered words that continue to spark controversy. Specifically, he told the jury that, although judges typically find the law and juries the fact, “you have nevertheless a right to take upon yourselves to judge of both, and to determine the law as well as the fact in controversy.”6 Some have called these words an “anomaly,”7 while others have considered them the foundation of the jury’s right to nullify.8 This Note’s conclusion that the Court once used a special jury of merchants, however, helps resolve this tension as well. The purpose of using a special jury of merchants was for the expert jury to help the judge determine the law merchant and incorporate it into the larger corpus juris. Thus, Chief Justice Jay’s words are more reasonable and less anomalous when we better understand the type of jury he was addressing.

In Part I, this Note begins by describing special juries in general and special juries of merchants in particular. Though dating back centuries, the practice of impanelling expert juries of merchants became especially prevalent in England and America in the second half of the eighteenth century, largely due to the influence of Lord Mansfield.

Part II discusses Brailsford in depth, while Part III details this Note’s original findings. After investigating the individuals who were called to be prospective jurors, this Note finds that ninety-five percent of them were merchants. This rate corresponds to that among special merchant juries impanelled in England. Further, this Note analyzes the unpublished oral arguments from the case. These arguments appeal to the “law of merchants,” mercantile custom, and the “prospects of future credit,” the precise types of arguments that attorneys would make to special juries of merchants. After examining several other strands of evidence, this Note concludes that the special jury impanelled before the Supreme Court in Brailsford was a Mansfieldian special jury of merchants.

In Part IV, this Note examines the subsequent history of juries in the Supreme Court, and the Court’s modern original jurisdiction practice. It then considers the possible scope of the Court’s discretionary power to decline to hear cases in its exclusive original jurisdiction. Finally, it considers whether a situation might ever arise in which the Supreme Court would be required to preside over a jury trial.

Part V examines how this Note’s conclusions affect the two questions presented by the case: (1) what happens when the Seventh Amendment confronts the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction; and (2) how we should understand Chief Justice Jay’s jury charge in Brailsford. As to the first question, this Note concludes that if the Supreme Court ever were constitutionally required to preside over a jury trial, it could impanel an expert jury just as it did in 1794—in essence, a special jury of special masters. As to the second question, this Note finds that Chief Justice Jay’s words were particularly appropriate for a special jury of merchants, because such juries were often tasked with determining the relevant mercantile custom that should control in a given case. Further, in America they were sometimes given the authority, with the judge’s instructions and oversight, to adopt that custom as a lasting precedent.

I. special juries

The term “special jury” refers to a jury that possesses some combination of three characteristics. First, “special jury” sometimes denotes a jury of experts, such as a jury made up of merchants for hearing commercial disputes.9 Second, “special jury” sometimes refers to a jury made up of upper-class individuals for hearing particularly important or sophisticated matters, the so-called “blue-ribbon jury.”10 Finally, the term “special jury” nearly always refers to a particular procedure of composing a jury, the “struck” jury, explained below.11 Some “special juries” had all three characteristics, others were “struck” but composed of the upper-class and not merchants per se, and still others were “struck” and made up of expert jurors, chosen for their expertise, and not necessarily their socioeconomic station. The practice of these “special juries” stretches back at least to the beginning of the seventeenth century,12 if not further. In particular, expert juries composed of merchants were used as far back as the fourteenth century.13

The institution of the special jury was codified in 1730 in England by statute.14 The procedure for composing a “special jury” or “struck jury” was as follows: Names of potential special jurors were regularly put on books and lists from which the clerk of the court could draw names for the venire facias.15 Certain books would contain the names of merchants for special juries of merchants.16 When it came time to impanel a jury, the clerk of the court, sometimes with the assistance of the parties,17 collate forty-eight “qualified” jurors. These qualifications could be based on expertise or property, depending on the type of special jury. The parties would then take turns striking off names from the venire until they reached the required number—thus the appellation “struck” jury.18 Although the practice of special juries in general, and special juries of merchants in particular, originated in the medieval period, Lord Mansfield brought special juries of merchants into widespread use upon his appointment as Chief Justice of King’s Bench in 1756. Under Mansfield, special juries of merchants became prevalent throughout England and the colonies in the late eighteenth century.19

Special juries of merchants served two main functions. First, they were sophisticated fact-finders whose expertise assisted them in understanding the complex facts underlying difficult cases. As Blackstone wrote of special juries in general, “Special juries were originally introduced in trials at bar, when the causes were of too great nicety for the discussion of ordinary freeholders . . . .”20 The second function of the special jury of merchants was to advise the court as to the prevailing custom in the law merchant, and, in the late eighteenth century, assist the judge in incorporating aspects of the law merchant into the wider body of common law.21

The law merchant, or lex mercatoria, was a system of mercantile customs, both locally and internationally derived. Blackstone, for instance, considered the law merchant to be a part of the law of nations.22 He stated that “in mercantile questions . . . the law-merchant, which is a branch of the law of nations, is regularly and constantly adhered to.”23 For Lord Mansfield, too, the law merchant was in part derived from the law of nations.24 As Judge Scrutton put it, “Mansfield . . . constructed his system of Commercial law by moulding the findings of his special juries as to the usages of merchants (which had often a Roman origin) on principles frequently derived from the Civil law and the law of nations.”25

The history of the law merchant is traditionally divided into three stages of development.26 In the first stage, encompassing medieval England until the beginning of the seventeenth century, mercantile cases were largely administered not by common law courts but by specialist mercantile courts27: courts of admiralty,28 arbitrators,29 and courts arising at fairs, markets, and ports.30 These merchant courts, often sitting with a merchant judge and a merchant jury, would arbitrate disputes using mercantile custom.31 These courts used a flexible procedure, allowing for both much faster results and a wider range of admissible evidence, in particular non-sealed instruments and mercantile custom.32 Ex ante, this body of merchant custom established a standard of appropriate behavior for mercantile dealings; ex post, the lex mercatoria allowed merchants to resolve their disagreements by looking to internal norms as opposed to external restraints.33

The second stage of law merchant’s development began with Lord Coke becoming Chief Judge of the Court of Common Pleas in 1606.34 In this phase, common law courts began to exercise more jurisdiction over the mercantile cases.35 In particular, in actions for assumpsit the common law courts began to allow proof of mercantile custom.36 The mercantile customs, however, were treated purely as matters of fact and not law. Thus, the litigants had to prove the prevailing mercantile custom as facts in each case, and none of the customs was codified as law by precedent.37 During this second stage, the specialty mercantile courts largely disappeared.38

The final stage of the development of the law merchant began in 1756 when Lord Mansfield became Chief Justice of King’s Bench.39 Sensing that England, now an international mercantile capital, lacked a body of mercantile law, Mansfield endeavored to incorporate the law merchant into the common law.40 He expanded the admissibility of prevailing mercantile custom, and allowed the common law to establish these customs as binding precedent.41

Mansfield used special juries of merchants to assist him in this project of incorporating the law merchant into the common law.42 He invited the special merchant jurors to “call[] upon their own experience and knowledge in reaching their verdicts.”43 Further, he would allow parties to argue merchant custom to the jury.44 Instead of having to prove a particular custom as a matter of fact in every case, Mansfield, with the assistance of his special juries of merchants, incorporated the law merchant into the common law and allowed these customs to become a part of the law itself.45 If the judge approved of the law merchant custom, he could make it a part of the corpus juris.46 In rare occasions, a prevailing mercantile custom might even serve to overturn contrary precedent and establish a new legal rule.47 As Oldham has put it, “What Mansfield did was to perceive how the special jury might be used instrumentally to establish legal principles by identifying mercantile practices and folding those practices into the common law.”48

In late eighteenth-century America, as in England, use of special juries of merchants was widespread.49 New York in particular followed England in commonly providing for special juries of merchants in complex commercial cases.50 South Carolina authorized special merchant juries for disputes between merchants,51 and made extensive use of them throughout the second half of the eighteenth century.52 Pennsylvania’s statute providing for special juries of merchants dated to 1701 and allowed a special jury to hear maritime mercantile disputes before a jury made up of “twelve merchants, masters of vessels or ship carpenters.”53 Special juries of merchants continued in use in Pennsylvania through the 1790s.54 Georgia by statute provided for “special jur[ies] of merchants” for disputes between “merchants, dealers,” and “ship-masters” concerning “contracts” and “debts.”55 Other states also had long made use of special juries of merchants.56 Expert special juries even made an appearance in one of the drafts of the Constitution in the summer of 1787.57

In America, moreover, judges would sometimes give special juries of merchants the authority to establish a particular rule of law for a given jurisdiction, although always with the advice of the judge. In Winthrop v. Pepoon, for instance, a common jury had heard the case in the first trial, and had assigned a particular quantum of damages.58 The defendants moved for a new trial, alleging that the method used to quantify the damages was contrary to the law of merchants, and asked that the new trial be heard by a special jury of merchants.59 As the report states, “the new trial was ordered in this case, not on account of any difficulty of the first part, but in order to have the point of damages established by a jury of merchants.”60 Counsel then argued the law merchant to the special jury of merchants.61 The court stated that the special jury of merchants “were now finally to settle this point; and therefore [the court] left it again to the jury now sworn . . . [to set the law] as they thought most agreeable to the law of merchants.”62 The report concludes that the jury’s finding of the appropriate quantum of damages “may be considered as establishing the law on this point.”63 Thus, special juries of merchants were at times relied upon to draw on their expertise of the law merchant in order to set the law for a certain jurisdiction.64

Another case where the judges left it to a special jury of merchants to ascertain a prevailing mercantile custom and establish it as the law was Davis v. Richardson.65 The question was what interest rate should apply to an otherwise silent debt.66 The plaintiff argued to the jury the custom of merchants in England.67 As the panel of judges stated per curiam to the special jury of merchants, although the case was not difficult, it “is of extensive importance to the community, that the principle should now be settled and ascertained with precision . . . and it is fortunate, that so respectable a jury are convened for the purpose of fixing a standard for future decisions.”68 The court then directed the jury to find for the plaintiff, and to establish a particular principle, and “[t]he jury found accordingly.”69

Thus, when the Court heard the Brailsford case in 1794, there would have been precedent throughout the Republic for convening such an expert jury. Moreover, there also would have been precedent for the judges treating such a special jury with a measure of deference, and even at times assigning to them the task of ascertaining the appropriate custom to incorporate into the general law, within the bounds of the judges’ instructions.

II. georgia v. brailsford

The dispute that eventually became Georgia v. Brailsford began during the Revolutionary War. Many states, including Georgia, enacted legislation that “sequestered” debts owed to British creditors.70 When the war ended, the 1783 Treaty of Peace between England and the United States established protections for foreign creditors.71 The Treaty stated in Article Four that “Creditors on either Side shall meet with no lawful Impediment to the Recovery of the full Value in Sterling Money of all bona fide Debts heretofore contracted.”72 Before the creation of federal courts, this provision had been de facto unenforceable; state laws, state judges, and state juries all sided with American debtors.73 But once the federal district courts opened their doors and dockets in 1790, foreign creditors rushed in.74

Georgia v. Brailsford was one such case. James Spalding, a Georgia citizen, owed Samuel Brailsford,75 a British subject,76 a bond dated 1774.77 Brailsford filed a suit at law against Spalding in Georgia federal circuit court in 1790 before two judges: Justice James Iredell, riding circuit, and Judge Nathan Pendleton. Georgia tried to interplead itself as the true plaintiff, stating that Spalding rightfully owed the debt to the state, not to Brailsford. Georgia argued that it had sequestered the debts of all British creditors by statutes it passed before the Treaty of Peace, and that the state had therefore replaced the British creditors.78 Justice Iredell believed that, if the state of Georgia interpled itself, the circuit court would not have jurisdiction to hear the case, since a state would be a party.79 Further, he had not heard of interpleading being allowed in a suit at law, as opposed to in equity.80 Therefore, Georgia’s petition was denied.81

Proceeding without Georgia as a party, the debtor Spalding deployed Georgia’s argument, namely that Brailsford could not collect from Spalding because Georgia was the true owner of the debt. The judges then set to work construing the words of Georgia’s statute. Section Four “confiscated to and for the use and benefit of the state” the “debts[,] dues and demands” owed to British citizens, “except debts or demands due or owing to British Merchants.”82 In the next section, the statute declared that “all debts[,] dues[,] or demands, due or Owing to [British] merchants” were “[s]equestered.”83

Judge Pendleton first argued that, by the statute’s own terms, “sequestered” and “confiscated” clearly had different meanings.84 He also construed the text by recourse to the law merchant, arguing that the Georgia legislature may have avoided confiscating the debts of British merchants because “debts contracted on the faith of commercial intercourse ought to be deemed of a sacred and inviolable nature . . . .”85 Judge Pendleton then stated that sequestration was a civil law, not common law, term meaning to deposit or entrust, and that therefore the right to collect Spalding’s debts never vested in Georgia; rather, ownership of the debt always remained with Brailsford.86 Moreover, even if Georgia had confiscated the debt, Judge Pendleton concluded, the Treaty of Peace trumped the state statute and revived Brailsford’s right to sue to recover his debt.87

Justice Iredell agreed with his fellow judge, and further argued that the custom of the law of nations regarding merchants suggested that the Georgia law would best be construed as not confiscating the debts.88 Justice Iredell echoed Vattel, the Swiss author of the definitive treatise on the law of nations, for the proposition that it is “agreeable to the modern practice in Europe not to confiscate Debts due to an Enemy.”89 Justice Iredell and Judge Pendleton found for Brailsford.90

Georgia then filed a bill in equity against Brailsford and Spalding in the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction, arguing that the Georgia statute, by sequestering the debt, had vested the right to collect the debt in the state, and that the Treaty of Peace did not affect that right.91 Brailsford objected to the bill in equity, arguing that since the law provided a complete remedy, there was no basis for the Court to hear the case in equity.92 Chief Justice John Jay, writing for the Court, agreed. On February 18, 1793, the Court held that it did not have jurisdiction to hear the bill in equity because Georgia could pursue its claim at common law.93 The Court told Georgia to file a suit at law the next Term,94 and enjoined disbursal of the debt until the case was resolved.95

The parties, however, did not know how to proceed at common law. Because the debt had not yet been disbursed to Brailsford, and the two parties had no contract between themselves, Georgia had no common law action against Brailsford.96 In order to try the case at common law, the two sides eventually agreed to a fictional set of facts.97 They stipulated that Brailsford had already received payment of the debt.98 Georgia then claimed, for the purposes of pleading, that Brailsford had promised to pay the debt to Georgia, while Brailsford denied the promise.99 Thus, issue was joined, and Georgia was able to sue Brailsford for trespass on the case based on these fabricated facts.100 The Supreme Court, although apparently aware that the facts were fictional,101 accepted the pleadings, and ordered the case heard the following Term.102

On January 13, 1794, attorneys for the two parties met to compose a special jury.103 They took turns striking names from a list of forty-eight merchants,104 until they reached twenty-four to be summoned, twelve of whom would serve as special jurors.105 On February 3, 1794, trial began before this special jury,106 the first time that the Supreme Court had sat with a jury. This was the first case on the Court’s docket for the Term, and had gained considerable publicity, at times referred to as “the famous Georgia case.”107

The Brailsfordcase presented two questions. First, when Georgia “sequestered” Brailsford’s debt, did the debt vest in the state? This first question was a matter of statutory interpretation. Second, if it did vest in Georgia, was the state’s title to the debt later abrogated by the Treaty of Peace?108 This second question concerned issues of the supremacy of treaties and state sovereignty. At this point in the proceedings, the Brailsford case did not concern any factual dispute, as the parties had stipulated all the facts.109

The counsel in this case argued the law to the Justices and jury.110 Alexander Dallas and Jared Ingersoll represented Georgia. They averred that when Georgia’s statute “sequestered” the debt, it had in fact confiscated it, and title to the debt had vested in the state. Calling the jury’s attention to such august authorities as Blackstone and Vattel, counsel for the plaintiff argued that Georgia had the authority as a sovereign state to confiscate the debts of an “alien enemy,” which it had intended to do by its sequestration.111 Moreover, Dallas cited to the same Vattel passage that Justice Iredell had referenced in his circuit court opinion,112 but this time for the opposite proposition: that, although disfavored and generally avoided, sovereignties did have the power to confiscate debts due to enemies in times of war.113 The plaintiffs then argued that Article Four of the Treaty of Peace only referred to “subsisting” debts, not sequestered or confiscated debts. They concluded that it was for the parties to the treaty, i.e., the states, and not the federal government, to construe its provisions.114

On the other side, William Bradford, Jr., the Attorney General of the United States, addressed the jury on behalf of Brailsford. He argued that Georgia had not confiscated the debt, but had merely sequestered it, meaning that ownership of the debt had never vested in the state. Moreover, he asserted that the Treaty of Peace had given creditors a right of action to recover their debts.115 These are the main arguments that Dallas, also the plaintiff’s attorney in this case, detailed in the official report.

There was, however, another side to Bradford’s oral argument that Dallas did not reproduce, which has consequently been left unanalyzed. As recorded in his notes, Bradford also extensively referenced the law merchant and mercantile custom in general.116 In the next Part, I will analyze these invocations of mercantile law and custom and the light they shed on the case.117

After four days of oral arguments,118 Chief Justice John Jay addressed the jury before it deliberated. He stated that the Court was of the unanimous opinion that Georgia’s statute did not confiscate but merely sequestered the debt. Therefore, Chief Justice Jay concluded, under the law of nations and the Treaty of Peace, resolution of the conflict with England revived Brailsford’s right of action to sue for recovery of the debt.119

Chief Justice Jay then addressed the jury on the subject of the distinction between law and fact. He first reminded the jury of the “good old rule” that questions of fact were the “province of the jury” and questions of law were the “province of the court.”120 “But,” he continued, “you have nevertheless a right to take upon yourselves to judge of both, and to determine the law as well as the fact in controversy.”121 He assumed that the jury would “pay that respect, which is due to the opinion of the court,” because “juries are the best judges of facts” and “the court are the best judges of law.”122 Nevertheless, he concluded, both the law and the fact were “within your power of decision.”123

After conferring among themselves, the special jury asked the Court whether the sequestration vested the debt in the state of Georgia.124 The Court responded that sequestration does not divest property, and that the right to collect the debt had never actually been taken from Brailsford.125 The special jury, “without going again from the bar,” found for Brailsford.126

III. the special jury in brailsford

What did it mean that the jury in Brailsford was a “special jury”? Scholars have generally assumed that there is no more specific information about what sort of a jury was convened in Brailsford, or how it was composed.127 This Part provides a detailed analysis of the extant documents referring to the special jury in Brailsford and concludes that the special jury was an expert jury, i.e., a special jury of merchants in the Mansfieldian tradition that was prevalent in America at the time.

As we have seen, the term “special jury” had several possible meanings.128 The “special jury” was virtually always created by the “struck” procedure. Moreover, a jury of merchants would also often qualify as an “upper-class” jury.129 An “upper-class” jury, on the other hand, while it would ordinarily contain merchants, would likely not overwhelmingly be made up of merchants.130 So which kind of special jury was the one impanelled in Brailsford?

Remarkably, the venire facias for Brailsford is extant, and offers insight into this question.131 The venire facias was the list of the forty-eight names collated in order to perform the struck procedure to impanel the special jury.132 The extant Brailsfordvenire is lacunose, but together with notes from the Supreme Court,133 forty of the forty-eight names from the original venire can be reconstructed. By analyzing the men who were chosen for prospective jury service, we can better understand what sort of special jury was composed for the Brailsford case.

For this Note, I have analyzed all of these names, and also all the names on the one other extant special jury venire facias, which the Supreme Court convened on August 1, 1796. For details on this analysis, see the Appendix, below. For the two special juries, the share of prospective jurors who were merchants is ninety-four percent. For the Brailsford jury venire alone, at least thirty-eight of the forty potential jurors were merchants, a ninety-five percent merchant rate. This equals the merchant rate of what appears to be a list of potential jurors for special juries of merchants in England.134

Moreover, the name “Robert Smith” in the Brailsford venire, and then again in the minutes of the Supreme Court, was designated as a merchant.135 Because there were at least three adults living in Philadelphia at this time named Robert Smith, one a merchant, one a mariner, and one a sailmaker,136 this presumably was meant to distinguish the merchant from the others, further suggesting a preoccupation with impanelling a jury of merchants.

A special jury of merchants in Brailsford would also be consistent with the widespread use of such merchant juries in America at this time.137 In particular, Pennsylvania, where the trial was held, New York, where Chief Justice John Jay had practiced law and had served as chief justice from 1775-1777,138 and Georgia,139 which was the plaintiff in this case, used special juries of merchants.

Perhaps the most suggestive piece of evidence that the Court in Brailsford employed a special jury of merchants, however, is the way that Brailsford’s attorney William Bradford argued to the jury. As preserved in his notes, Bradford appealed to mercantile law and custom at length to the jury. Bradford told the jury that the statutory construction for which Georgia argued would be “opposed” to “[t]he principle of the Mercantile law.”140He went on, telling the jury that “many merchants [would be] well affect[e]d” by an adverse ruling.141 “[T]he faith of Commercial intercourse ought not to be violated,” he argued, referencing Judge Pendleton’s suggestion in the lower court that the law merchant should be used to construe the text of the Georgia statute and the intent of the legislators.142 Bradford went on to ask the special jury about the “Prospect of future Credit,” if they ruled against this bona fide creditor, before referencing the “[rule] of merchants.”143 Thus, Bradford’s arguments to the jury on behalf of Brailsford made extended invocations of mercantile law and custom in order to persuade the jury to embrace his client’s position.

These were precisely the sorts of arguments that attorneys would make to special juries of merchants. Attorneys would regularly argue that their opponent’s argument was not “conformable to the general sense and usage of merchants,”144 or “conformable to the law of merchants.”145 The parties would bring witnesses to argue to the jury what was the “common practice, in dealing with respectable merchants.”146 In short, the arguments that Bradford made to the special jury in Brailsford were exactly what one would expect if he were arguing to a special jury of merchants.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court possessed the power and inclination to imitate the special juries of merchants frequently used at King’s Bench.147 The Judiciary Act of 1789 gave the federal courts the power to establish their own procedural rules.148 The Supreme Court accordingly in 1792 adopted the procedures of the English courts King’s Bench and Chancery.149

The Brailsford case, moreover, was particularly appropriate for a special jury of merchants. As we have seen, special juries of merchants served two purposes. First, they provided mercantile expertise. This would have been helpful for a complex case like Brailsford. The case revolved around the issues of debts changing hands and vesting, and it concerned a wide variety of partnerships and parties who acted as plaintiffs in one action and defendants in the next.

The second function of a special jury of merchants was to advise the court on the controlling mercantile custom from the law merchant, and, if the law was unsettled, to assist the court in incorporating that custom into the corpus juris. In Brailsford, this was the only task for the jury, as all the facts had been stipulated.150 As Chief Justice Jay put it in the beginning of his charge to the jury, “The facts comprehended in the case, are agreed; the only point that remains, is to settle what is the law of the land arising from those facts; and on that point, it is proper, that the opinion of the court should be given.”151 Thus, the special jury was to help decide the case, with the advice of the Court, and thereby to help settle the law of the land. As we have seen, such special jury charges that outlined the opinion of the court, but left it to the merchants to establish binding precedent on the issue, were a part of the American legal system.152

Moreover, Brailsford focused on the precise matters that special juries of merchants had always been called on to decide: the law merchant. The case would decide how to construe state acts sequestering foreign debts, and how the subsequent Treaty of Peace affected those statutes. The parties argued to the jury that the state acts should be construed in light of international law merchant norms. They further argued that the Treaty of Peace should be construed by reference to the law of nations. These international mercantile customs constituted the core of special merchant juries’ expertise.

Thus, the evidence suggests that, in its first decade, when the Supreme Court was confronted with the prospect of presiding over a case at law touching on the major issues of the law of nations and mercantile law, it turned to a special jury of merchants to help decide the case.

IV. juries in the supreme court and the scope of the court’s discretion to decline cases

This Part examines the subsequent history of juries in the Supreme Court. It then discusses the modern Court’s prevalent use of special masters instead of juries as fact-finders in cases within its original jurisdiction. It next considers the scope of the Court’s discretionary power to decide which cases to hear in its original jurisdiction, and which to decline. Finally, it considers what sort of case at law might require the Court both to hear it and to impanel a jury.

Beginning with Brailsford, the Supreme Court regularly impanelled a jury at the beginning of each of its biannual Terms in February and August.153 The first jury was impanelled for Brailsford in February 1794.154 In August 1794, the Court called a jury to determine damages in the wake of Chisholm v. Georgia,155 but dismissed it when it became clear that there were no issues to determine at that time.156 In February 1795, one year after its first jury trial, the Court again presided over a jury trial in the unpublished case of Oswald v. New York, which remains the only case before the Supreme Court in which a private citizen sued a state for damages before a jury and won.157 In August 1797, the Supreme Court heard its third and apparently last jury trial, the unpublished case Cutting v. South Carolina.158 The Court again discussed summoning a jury in August 1798, apparently for the last time, but did not do so.159

For more than two centuries since 1797, the Supreme Court has avoided presiding over a jury trial. The Seventh Amendment does not apply to bills in equity, and therefore in such cases it is within the Court’s discretion whether or not to impanel a jury.160 The Court has held that a jury is “not necessary” to decide a few simple facts,161 and that in such cases a commissioner’s report summarizing his findings can be “considered . . . of the same force as a verdict of a jury.”162 In one case at common law that the Court did hear, the parties waived their right to a jury trial.163 Justice Douglas has even suggested several times that it isan open question whether the Seventh Amendment applies at all to the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction.164

Because the Court has not heard a case that would require a jury over the past two centuries, it has had to look elsewhere for fact-finders in the equity cases it does hear. In the nineteenth century, the Court largely acted as its own fact-finder, although it would sometimes appoint commissioners to ascertain particular points of fact.165 Today, however, when the Court accepts an original jurisdiction case it calls a special master to act as fact-finder,166 granting to this position a combination of the traditional jury role and certain functions of a trial-court judge.167 The special master presides over the proceedings and delivers to the Court a summary of them.168 This initial proceeding allows the Court to act in a manner analogous to an appellate body.169 The proceedings presided over by special masters do not use juries,170 and it is doubtful that they could, considering the Court’s ruling that, at least in a criminal case, magistrates exceed their authority if they impanel a jury.171

The practice of delegating fact-finding in original jurisdiction cases to special masters has become institutionalized, although some commentators172 and Justices173 have expressed discontent with the procedure. Moreover, some Justices have been critical of the idea that special masters’ findings should be accorded any deference.174 This has not prevented the Court, however, from regularly appointing special masters in all of its original jurisdiction cases.

In these original jurisdiction cases, moreover, the Court has not followed its traditional maxim that courts may not decline to exercise their jurisdiction.175 Because the overwhelming majority of cases in the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction sound in equity,176 the Court often refuses petitions on the equitable basis of alternative fora.177 In 1971, the Court unambiguously announced that it had the power to decline to hear a case within its concurrent original jurisdiction,178 because as an appellate tribunal it was “ill-equipped for the task of factfinding.”179 It has regularly applied this doctrine.180 More controversially, however, the Court has also asserted that it may decline to hear cases in its exclusive original jurisdiction.181 Both commentators182 and Justices183 have criticized this practice, and it may not entirely be in favor.184 Nevertheless, the Court has not officially repudiated it.

California v. West Virginia has elicited particular criticism for the assertion that the Court may decline to hear cases within its exclusive original jurisdiction. The case concerned a contract claim brought by California against West Virginia. The contract arranged for two collegiate football games between the San Jose State Spartans and the West Virginia Mountaineers, two state university teams. When West Virginia allegedly broke the contract, California sued in the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction.185 The Supreme Court denied leave to file, likely because the Justices did not consider this case to be weighty enough to merit the Court’s attention.186

Justice Stevens dissented, arguing that the Court cannot refuse to hear cases in its original jurisdiction where Congress has made that jurisdiction exclusive.187 David Shapiro, although a proponent of courts’ broad discretion to decline to hear cases, called Justice Stevens’s dissent “unanswerable,” and argued that “[a] grant of exclusive jurisdiction to resolve certain controversies should be read as depriving the court of discretion to determine that it is an inappropriate forum, at least when the ‘appropriate’ forum lacks jurisdiction under the terms of the granting statute.”188

California v. West Virginia, however, could have been even more interesting from a jurisdictional point of view. The case concerned a breach of contract, an injury whose remedy could sound in either law or equity. California filed a motion for leave to file a bill of complaint, which is usually an equitable action. The state could, however, have pursued an action at law for damages without seeking any equitable remedies, in which case two interesting complications may have resulted.

The first complication is the possible application of the Quackenbush principle to the Supreme Court’s exclusive original jurisdiction discretion. Quackenbush held that federal courts have the power to dismiss or remand cases based on abstention principles only where the relief sought is equitable, and not in common-law actions for damages.189 Because declining to hear a case within the Court’s exclusive original jurisdiction is not dissimilar to dismissing a case based on abstention principle, the Quackenbush principle may cast doubt on the Supreme Court’s discretion to decline to hear common law cases in the Court’s exclusive original jurisdiction.

Second, and more pertinent to our present purposes, consider a hypothetical California v. West Virginia suit that was at law instead of equity. Such a case may be in the Court’s mandatory jurisdiction, as we have seen. Moreover, the Seventh Amendment would seem to apply, even though both parties were states.190 Indeed, in the only cases where this issue has been considered, federal courts of appeals have found that, based on the historical test, the Seventh Amendment does apply to states, at least when the state is a defendant,191 or is a plaintiff and is asserting a proprietary interest and also acting as parens patriae.192 As the Ninth Circuit held in Standard Oil Co. of California v. Arizona, states are analogous to the sovereign, and the Crown historically had the right to a jury.193 Thus, if California v. West Virginia had been a case at law, the Seventh Amendment may have applied to it, in which case the Court would have had to confront the jury issue.

Indeed, there may come a time when the Seventh Amendment and the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction collide, and the Court may be forced to preside over a jury trial. As discussed in the next Part, this Note’s contribution to our understanding of the Court’s early practice with juries may provide assistance to the Court in navigating such a constitutional mandate.

V. addressing the puzzles posed by brailsford

A. The Seventh Amendment and the Supreme Court’s Original Jurisdiction

Some commentators have argued that a jury trial before today’s Supreme Court would be unworkable, and should be avoided at all costs.194 The image of the Supreme Court presiding over a jury trial seems so incongruous to modern commentators that some have searched for a reason why the Court could possibly have used a jury in Brailsford.195 The simple explanation, however, is that Brailsford was a case at law, and therefore the Seventh Amendment mandated a jury trial. Indeed, scholars still generally agree that the Seventh Amendment would apply to cases at law within the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction.196 Moreover, Congress continues to mandate juries to try issues of fact in all common law cases against U.S. citizens in the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction, just as it has since 1789.197 As Wright and Miller have stated, the application of the Seventh Amendment to cases at law in the Supreme Court, in particular those disputes between states in the Supreme Court’s exclusive original jurisdiction, “may raise unanswerable questions.”198

Thus, there may be a case at law in the future that requires the Court to convene a jury, especially considering the possibly circumscribed status of the Court’s power to decline to hear cases that fall within its exclusive original jurisdiction when no alternative forum is available.199 It may be a case between states, or when one party is an ambassador, or when a state sues an out-of-state individual. At some point the Court may even be amenable to or desirous of hearing an issue of great importance in its original jurisdiction, perhaps for expediency purposes. Indeed, the Court has reached out to exercise its original jurisdiction in a number of high-profile cases in the past. These cases have examined such issues as whether Congress could require states to register eligible citizens between the ages of eighteen and twenty-one to vote in state elections,200 whether Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act was constitutional,201 and whether a provision of the federal tax code violated the Tenth Amendment.202 In the future, such a case may be at law and constitutionally require a jury, and the parties may insist on it.

The hitherto untold details of the special jury in Brailsford that this Note has uncovered may provide the Supreme Court with a way of managing the burden of sitting with a jury: impanelling a jury of experts. Historically, one reason to convene a special jury was for its expertise in a particular area.203 Thus, in cases of great complexity and national import, the Court may feel more comfortable using a jury of experts that it impanels together with the parties in order to have sophisticated individuals finding complex and sensitive facts. Such a jury of experts, moreover, may be agreeable to the parties, especially if they are able to help compile the initial venire, as was sometimes the case with special juries.204 With this deeper understanding of Georgia v. Brailsford, the Court has a broader range of ways to negotiate its original jurisdiction and the Seventh Amendment.

One potential source of expert jurors is the same pool of individuals from which special masters are drawn, creating a special jury of special masters. Such a panel would not be historically unprecedented under the Seventh Amendment test.205 In 1737, King George II appointed a twenty-person commission to determine the facts of a dispute over the boundary between Massachusetts and New Hampshire; the Privy Council ultimately heard the case, and accepted the commission’s legal recommendation.206 In the 1790s, too, the Supreme Court delegated the task of taking depositions in two original jurisdiction equity cases to commissions made up of prominent men.207

Thus, an appropriate course of action for the Supreme Court, were it required to impanel a jury in the future, would be to compose an expert special jury: a special jury of special masters. To be sure, there has been considerable controversy associated with treating special masters like juries or according their findings any deference.208 For such a special jury to be valid, it would have to be composed as special juries were at common law: collated with the consent and even participation of the parties, impanelled through the struck procedure, and placed under oath. If all of these requirements were complied with, however, a “special[ist] jury” may offer the Court a realistic and constitutionally valid method of complying with the Seventh Amendment in its original jurisdiction.

B. Brailsford and the Power of the Jury

This Note’s findings may also help resolve the lingering uncertainty over the meaning of Brailsford’s statements regarding the jury’s power to find the law.

Chief Justice Jay’s jury instructions in Brailsfordhave presented something of a puzzle for scholars. On the one hand, Brailsford is invariably the case cited for the proposition that juries had law-finding power at the Founding.209 Citing Brailsford, some scholars conclude that early American juries “determined questions of law,”210 and indeed, “quite generally . . . determined the law in civil cases.”211 One scholar has stated that “[i]f there was any doubt about whether the jury’s right to decide issues of law had survived the American Revolution, such doubt was promptly laid to rest in the 1794 case of Georgia v. Brailsford.”212

Other commentators, however, have noted that Chief Justice Jay’s instructions to the jury fit better with criminal cases, in particular seditious libel prosecutions, but are aberrant in a civil trial context. For instance, in Sparf v. United States, the case often cast as Brailsford’s antithesis, Justice Harlan wondered whether Brailsford had been misreported, considering that it gave the jury the right to decide the law in a civil case.213 Several scholars have also argued that in a civil case, Chief Justice Jay’s language was “anomalous.”214

This Note’s findings offer insight into this difficulty as well, revising the traditional understanding of Brailsford as an anomalous statement regarding jury rights on the one hand, or an uncomplicated espousal of civil jury nullification on the other. If, as this Note has argued, the special jury in Brailsford was a special jury of merchants, then Chief Justice Jay’s instructions fit better with historical practice. As discussed above,215 special juries of merchants were impanelled precisely to assist the court in ascertaining mercantile law and incorporating it into the corpus juris. As Oldham has shown, “the special jury was used frequently and instrumentally by Lord Chief Justice Mansfield in the shaping of a coherent body of commercial law.”216 In cases with special juries of merchants throughout the common law world, those juries would inform the court of a prevailing mercantile custom, and the judge could then incorporate that custom of the law merchant into the general law if he felt that it was appropriate.217 In America at this time, moreover, where there was not yet a well-established mercantile law, judges could leave it to a special jury of merchants to establish as law the custom that they considered most in harmony with the international law merchant.218

Thus, if understood in its context, Chief Justice Jay’s jury charge includes the natural instructions that a judge in a trial at bar would give to an expert special jury of merchants, which was expected to play a part in incorporating mercantile law into the larger body of law. After all, the facts in Brailsford had already all been stipulated,219 and thus finding the law was the only matter left for the special jury to determine. In the case of Brailsford, a special jury of merchants would be expected to apply to this case the prevailing law merchant customs. This would assure the wide mercantile community that the courts of the nascent Republic would not be insular and partisan, but would apply the lex mercatoria to international mercantile disputes.220

It is important to recognize that Mansfield’s use of special juries of merchants did not violate the rule that judges find the law and juries the fact.221 His special juries would ascertain the appropriate controlling custom by looking to their own expertise, counsel’s and witnesses’ appeals to the law merchant and prevailing practices, and finally the judge’s instructions. After the jury determined the case, the judge would then decide whether to establish the custom as a rule of law; that is, whether to incorporate the mercantile custom into the common law.222 Thus, judges in England during the second half of the eighteenth century were in control, but special juries of merchants did participate in this process of transforming mercantile custom into precedent with the force of law.223

Special juries of merchants in America during the 1780s and 1790s also did not violate the separation between judge-found law and jury-found fact. Nevertheless, it was more common there for the special jury of merchants to decide what the prevailing law should be, based on their own expertise and knowledge of the international law merchant, as well as on the judge’s own instructions.224 The judges may have relied so heavily on the expertise of the special juries in part because of the dearth of legal expertise on American benches at the beginning of the Republic.225 Moreover, late eighteenth century America was particularly amenable to incorporating customs more generally into the prevailing law.226 Finally, this fledgling system of government, saddled as it was with foreign debts and conscious of the need for future borrowing, recognized the importance of conforming their mercantile law to prevailing law merchant norms.227

For special juries to assist in establishing a prevailing custom as law is not the same as finding against the evidence or nullifying established law. This Note does not comment on the extent to which juries possessed such a power in civil cases at the beginning of our Republic. It is clear, however, that in the late eighteenth century, if a jury found against the evidence or against the law, or even found against the judge’s instructions, the losing party would likely move for a new trial.228 When the law was unsettled to begin with, however, it was more difficult for the case to result in a new trial. To be sure, Mansfield on occasion would call for a new trial when he disagreed with the conclusion of the special jury of merchants.229 But it was rare for Mansfield to do so if the result was neither against the evidence nor against the law, even when he heartily disagreed with the verdict.230 Indeed, in the late eighteenth century, the conclusions of special juries of merchants were accorded particular deference by English judges, at least when they did not contravene law already on the books.231 Even when they did conflict with existing law, moreover, Mansfield on occasion would overturn precedent and incorporate a mercantile custom as the new law on the matter.232 Even here, however, the judge remained in control of the proceedings, the extent to which the custom was entrenched as precedent, the amount of deference accorded to the special jury’s expertise, and whether to grant a new trial. The special jury, meanwhile, remained in control of the final outcome of a particular trial, even if it was later overturned for a new trial.

Thus, when understood in their original context, Chief Justice Jay’s words to the special jury in Brailsford are neither aberrant nor the font of nullification power. Instead, they are the appropriate words addressed to a particular juridical body tasked with particular responsibilities.

Conclusion

This Note has shed light on the early, yet still controversial, case of Georgia v. Brailsford. It has examined the extant primary source material related to the case, in particular the venire facias and the notes from counsel’s oral arguments. It has shown that the venire was almost exclusively made up of merchants, and that Brailsford’s attorney repeatedly invoked the law of merchants in his address to the jury. It has concluded from these and other strands of evidence that in the Supreme Court’s first and only reported jury trial, it employed a special jury of merchants in the Mansfieldian tradition.

As this Note has argued, this discovery about Brailsford offers insights into the two provocative questions that emerge from the case. First, could there ever be a case in the future that would require the Supreme Court to preside over a jury trial, and if so, how should the Court convene such a jury? Second, what did Chief Justice John Jay mean when he informed the Brailsfordjury that they had both the power and the right to determine the law?

This Note has argued that there may in fact be situations in the future in which the Supreme Court may be amenable to hearing, or may even be required to hear, a case in its original jurisdiction that necessitates a jury trial. By looking to its history, the Court may wish to imitate its forebears and impanel a jury of experts, a “special jury of special masters.” Such a jury may reduce concerns that the Court might have regarding presiding over a jury trial.

The findings of this Note also suggest that Chief Justice Jay’s jury charge was neither “anomalous” nor an expression of ubiquitous jury nullification power. Instead, his words may have been tailored to the particular jury he addressed. Because courts often used special juries of merchants to determine the mercantile custom—to help the court decide a matter of law and incorporate the law merchant into the wider corpus juris—Chief Justice Jay’s words were particularly appropriate for such a panel.

Appendix

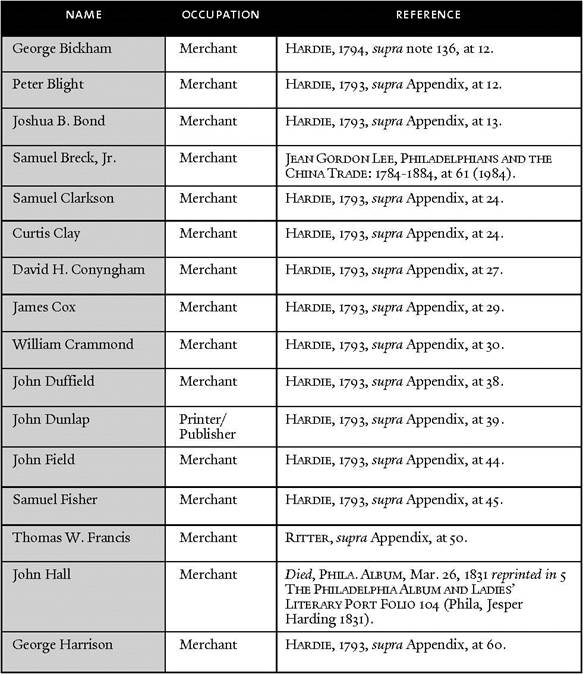

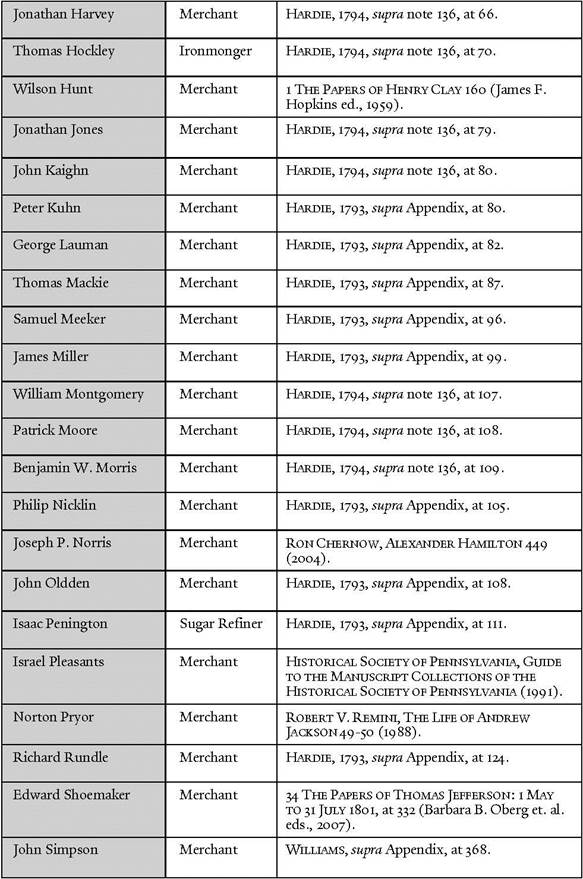

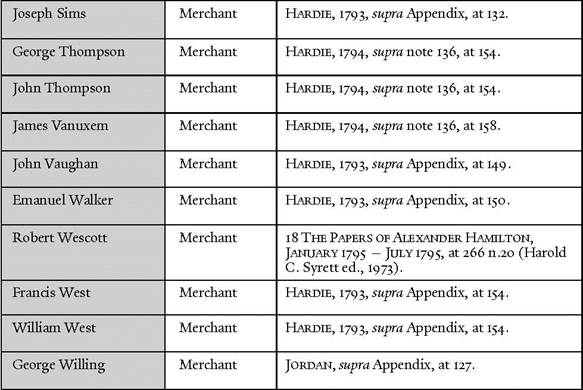

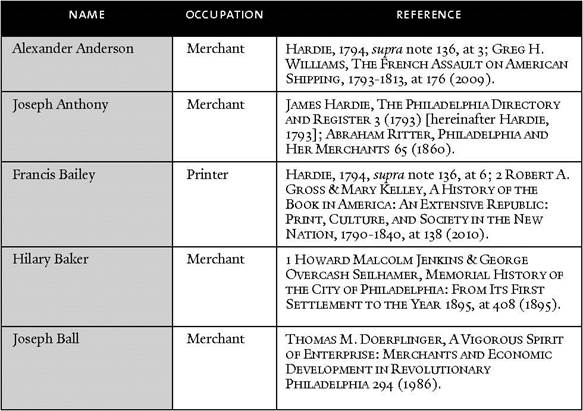

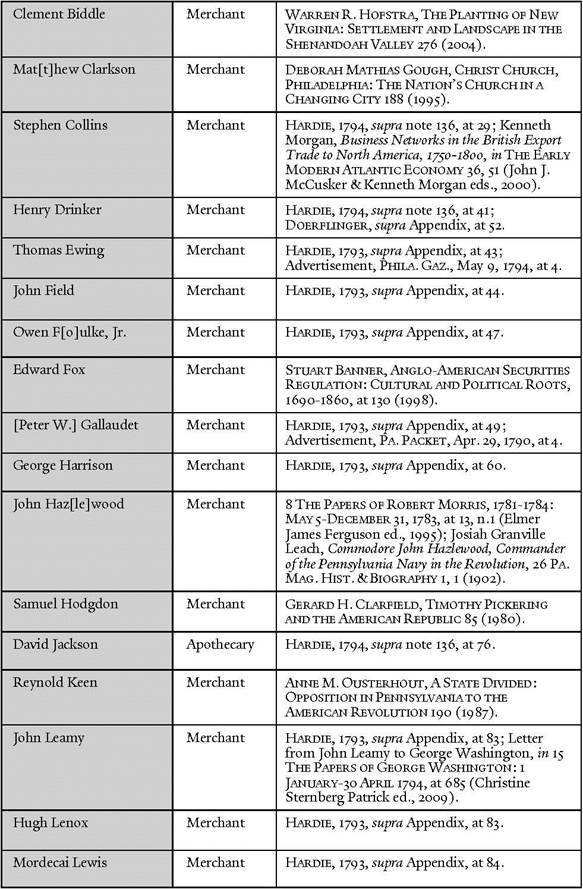

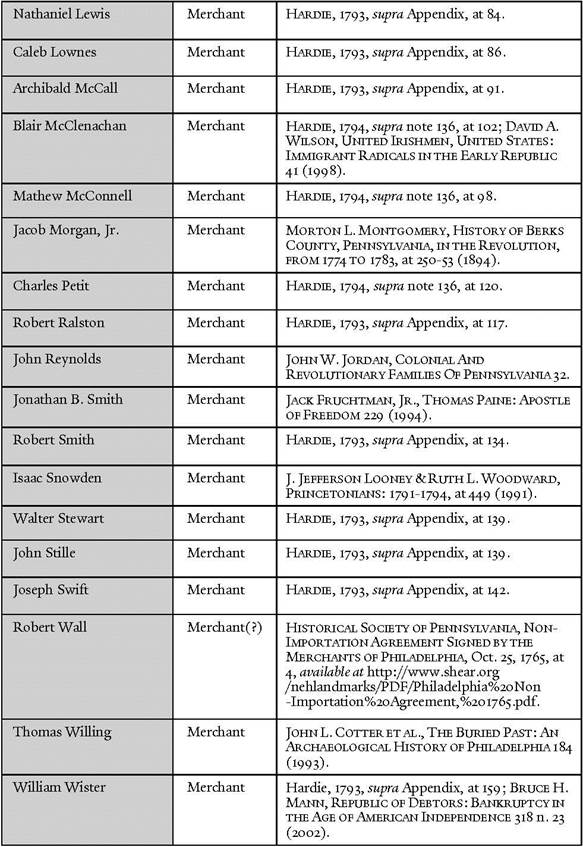

This Appendix analyzes all of the individuals who were designated as prospective jurors before the Supreme Court in a special jury. The list provides the occupation of each individual. Of the prospective jurors for the special jury called in Georgia v. Brailsford, at least 38 of the 40 names are merchants, for at least a 95% merchant rate. Of the prospective jurors for the special jury called in 1797, 45 of the 48 names are merchants, for a 94% merchant rate. Some names are spelled inconsistently in the primary sources. I have chosen the spelling most frequently attested. If more than one individual in Philadelphia possessed one of the names from the list of potential jurors, I have assumed that the parties intended to designate the merchant.233

Table 1.

prospective jurors for the special jury in georgia v. brailsford, with their occupations234

Table 2.

prospective jurors for the special jury from august, 1796, with their occupations235