Present at Antitrust’s Creation: Consumer Welfare in the Sherman Act’s State Statutory Forerunners

abstract. For the last four decades, federal courts have construed the Sherman Act as a consumer-welfare statute. But considerable disagreement persists within the legal academy regarding the true legislative aims of American antitrust law. This Note argues that interpreters of the Sherman Act ought to look more closely at an understudied branch of antitrust—state antitrust statutes enacted contemporaneously with the Sherman Act—to better understand the roots of federal antitrust law. The Sherman Act’s legislative history indicates that Congress intended to prohibit the same combinations in restraint of trade that were already prohibited by state statutory and common law. The plain language of the Sherman Act’s state predecessors shows that most were designed to promote what we now call consumer welfare. These statutes prohibited only those business combinations that harmed consumers by artificially constraining the supply of consumer goods. Read in this context, the Sherman Act is properly understood as the federal component of a national program on behalf of consumer welfare.

Yale Law School, J.D. 2015. I am especially grateful for the direction and advice I received on this project from Professor George Priest. Professors Herbert Hovenkamp and Dale Collins provided valuable feedback on the first drafts. Jennifer Yun, Rebecca Lee, Michael Clemente, and the editors of the Yale Law Journal strengthened this Note through their thoughtful questions and suggestions. Any errors are mine.

Introduction

In an age of ever more complex congressional enactments, the Sherman Act stands out as an unusual piece of legislation. The 125-year-old core of American antitrust law remains powerful and ubiquitous: between 2012 and 2014, it gave rise to prosecutions generating $3.4 billion in criminal fines across a range of industries.1 Yet it was drafted with semantic economy, rendering its meaning elusive. In just ninety-six words, section 1 of the Act prohibits all agreements “in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States.”2 Section 2 of the Act, in eighty-two words, imposes criminal penalties on “[e]very person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize . . . any part of the trade or commerce among the several States.”3 The law’s Delphic language, together with Congress’s infrequent modification of the federal antitrust regime, has led some to conclude that “[t]he Sherman Act set up a common law system in antitrust.”4

Notwithstanding occasional invocations of the judiciary’s “common law” authority over the Sherman Act, federal courts have, since the Act’s earliest days, expended great energy attempting to divine the legislative purpose behind it.5If the Sherman Act were truly a blanket grant of common law-making authority to federal courts, they would hardly need to undertake such searching inquiries. The Supreme Court’s and lower courts’ close attention to the Sherman Act’s language and legislative history indicates that they have sought to abide by their constitutional role as interpreters of federal statutes.6

It is therefore more precise to say that the judiciary enjoys an especially wide authority to fill statutory gaps when interpreting the Sherman Act due to the Act’s ambiguous language, its constancy over time, and the fact—peculiar in light of many modern regulatory regimes—that Congress did not assign rulemaking authority to an administrative agency. These traits do not imply that federal courts may pursue whatever antitrust policy they find most desirable or wise; courts are obliged to follow the statute’s contours to the extent that they can perceive those contours.7

The judiciary’s evolving understanding of the Sherman Act has dramatically affected the scope of antitrust law in the United States. The Supreme Court first purported to strictly construe the Act’s prohibition of “every contract . . . in restraint of trade,” noting that “no exception or limitation can be added without placing in the act that which has been omitted by Congress.”8 The Court later set aside the statute’s plain meaning9 and seized upon the statute’s use of common-law language to derive a common-law “rule of reason” prohibiting only those agreements that “unreasonably”restrained trade.10

In the middle of the twentieth century, the dominant reading shifted. In the legislative history of the Sherman Act courts found a congressional intent to preserve competition for the benefit of other producers. In his famous Alcoa opinion, Judge Hand wrote that “Congress . . . was not necessarily actuated by economic motives alone. It is possible, because of its indirect social or moral effect, to prefer a system of small producers, each dependent for his success upon his own skill and character.”11 He cited the Congressional Record for the proposition that the Sherman Act was designed “to put an end to great aggregations of capital because of the helplessness of the individual before them.”12 In cases like United States v. Von’s Grocery Co., the Supreme Court invoked Congress’s general fear of “concentration,” and adopted the view that the purpose of the Sherman Act was “to prevent economic concentration in the American economy by keeping a large number of small competitors in business.”13

Change came yet again in 1966. Robert Bork, then an antitrust professor at Yale, delved into the Senate debates over the Sherman Act and concluded that Congress’s legislative intent in enacting the Sherman Act was to “maximiz[e] . . . consumer welfare,” without regard to the interests of competitors.14 Within a decade, lower federal courts began signing on to this proposition.15 In 1979 the Supreme Court unanimously concluded, “Congress designed the Sherman Act as a ‘consumer welfare prescription.’”16 The Court has since repeatedly affirmed that interpretation.17

Putting aside the modern judicial consensus, the statutory underpinnings of the consumer-welfare theory remain shaky. The text of the Sherman Act, of course, says nothing about “consumer welfare,”18 and there is a general sense within the legal academy that Bork reached his conclusions by cherry-picking from a complex and contradictory legislative history.19 Subsequent studies of the Sherman Act’s legislative history revealed other policies, including producer welfare,20 protection of consumers and small suppliers,21 and prevention of an accumulation of “excessive social and political power” in the hands of monopolists.22 Barak Orbach summarizes a widespread view: “The legislative history of the Sherman Act has been studied thoroughly during the past century. There is broad agreement today, if not consensus, that the record does not support the historical claims that led to the adoption of the consumer welfare standard.”23 Reflecting on the scholarly debate, one introductory antitrust casebook advises students, “[Y]ou . . . may be tempted to try to ascertain the congressional intent underlying [the Sherman Act]. No matter how much you research the history of the Act . . . you are unlikely to find convincing answers.”24

This Note proposes that convincing answers can be found outside the immediate legislative history of the Sherman Act, in a body of pre-Sherman Act statelaw. In particular, thirteen state antitrust statutes and five state constitutional antitrust provisions—adopted while Congress debated the Sherman Act between 1888 and 1890—shed light on the policy underlying the Sherman Act.

Consulting state legislation may seem like an odd way to derive the meaning of a federal statute as foundational as the Sherman Act. But, as Part I argues, it follows an old canon of statutory interpretation, in pari materia, which advises courts to read related statutes in harmony where the statutes are part of an “integrated scheme” of regulation.25 Though the legislative history of the Sherman Act contains few sure answers, there is wide agreement that Congress intended the Act to work in concert with state antitrust law, providing a federal forum for targeting the anticompetitive combinations that were already illegal in the states.26

Part II explores the text of the state statutes and constitutional amendments and finds a clear pattern among them. Far more detailed than the Sherman Act, these statutes and constitutional amendments articulated the states’ original consumer-welfare policy. This policy had three major features. First, it emphasized the principle of allocative efficiency. In other words, most state statutes prohibited only arrangements that had the effect of raising prices for consumers by restricting productive output. Second, this policy protected consumers not by reference to overall social output, but by reference to industrial output in discrete product markets. Third, it incorporated a mens rearequirement, making antitrust liability contingent on an actual intentto harm consumers through restrictions on output.

Part III brings the original consumer-welfare policy into the present day, briefly explaining how the approach embodied in the early state antitrust statutes would address some of the unresolved questions in modern antitrust law. It first explores how the original consumer-welfare policy differs from competing standards advanced by scholars, such as “total welfare” and “competition” standards. It then explains why the original consumer-welfare policy is consistent with the Supreme Court’s present consumer-welfare approach, which has generally moved antitrust law away from per seliability standards and toward individualized assessments of consumer harm. The federal courts’ current focus on consumer welfare should be understood not as a modern contrivance, but as a faithful application of the Sherman Act as it was written.

I. state antitrust legislation and the sherman act, in pari materia

A long-established principle of statutory construction holds that “if divers[e] statutes relate to the same thing, they ought all to be taken into consideration in construing any one of them, and it is an established rule of law, that all acts in pari materia are to be taken together, as if they were one law.”27 Although “the rule’s application certainly makes the most sense when the statutes were enacted by the same legislative body at the same time,”28 the Supreme Court and other federal and state courts have treated related federal and state statutes in pari materia where it is clear that one statute is intended to work in concert with the provisions of another.29

Statutes that work in pari materia might not say so on their face, and courts—including those favoring textualist interpretive approaches—make use of legislative history to determine whether one statute is intended to incorporate the provisions of another.30 As Caleb Nelson explains,

At a minimum, when courts conclude that two statutes are part of an integrated scheme, courts will resist reading those statutes to work at cross-purposes. More broadly, courts often try to resolve indeterminacies in one statute in a way that keeps the statute in tune with the policies behind other statutes that are in pari materia.31

In accord with the in pari materia canon, federal and state courts have frequently treated judicial constructions of the Sherman Act as binding or persuasive authority in construing analogous state statutes passed after the Sherman Act’s adoption in order to avoid conflicts between state and federal antitrust policies.32

The same principle of statutory interpretation should extend to America’s first codified antitrust laws: the antitrust statutes and constitutional provisions passed by state legislators while Congress debated the Sherman Act. These statutes were part of a legislative conversation between Congress and the states, and the Sherman Act’s legislative history shows that Congress intended the federal and state antitrust laws to work together as part of a cohesive national regulatory scheme. Courts and scholars should therefore examine the Sherman Act’s legislative purpose in light of these state-law antecedents.

Admittedly, reading a federalstatute—particularly one as foundational as the Sherman Act—in light of state law might strike some as unconventional. It should not. Federal courts regularly read federal statutes in light of preexisting state common-law decisions when Congress incorporates terms from the common law in its statutes.33 For many years, courts34 and commentators35 have understood the Sherman Act’s operative terms as common-law terms that should be interpreted in light of preexisting state case law, such as the Michigan Supreme Court’s decision in Richardson v. Buhl,36 of which Senator John Sherman took particular notice on the floor of the Senate.37 Federal courts read these state common-law precedents into the Sherman Act on the understanding that Congress intended to prohibit interstate trusts to the same extent as they had been prohibited at the intrastate level by state law.38 But those same courts have long relied solely on state judicial opinions to understand the state-law landscape at the time of the Sherman Act’s adoption.39 This focus on state judicial opinions has neglected the content of local legislation—state constitutional and statutory law—that took shape as Congress debated the Sherman Act. Congress intended for the Act to work in harmony with that legislation, just as it intended for federal antitrust law to follow the contours of common-law prohibitions on conspiracies in restraint of trade.40 Taking notice of state statutes in pari materia provides another way of understanding the antitrust prohibitions that Congress sought to enforce at the interstate level when it passed the Act.

A. The Legislative Conversation Between the Senate and the States

Seventeen states drafted measures contemporaneously with the Sherman Act in a wave of public backlash against monopolistic trusts’ growing control of various industries in the 1880s.41 These trusts included famous aggregations like the Standard Oil petroleum refining monopoly and the mighty Sugar Trust, but also a host of trusts cornering more obscure markets such as the School Slate Trust, the Envelope Trust, and the Paper Bag Trust.42 As William Letwin recognized in his canonical study of the Sherman Act’s legislative history, news articles and editorials attacking the trusts were the daily fare of major newspapers like The New York Times and The Chicago Tribune in the late 1880s.43 Opponents of the trusts, one commentator colorfully explained, saw the new class of monopolists as “merciless and cruel exploiters, completely selfish, living by no rules and guided by no ethics.”44 Letwin summed up more modestly, “In the years immediately before the Sherman Act, between 1888 and 1890, there were few who doubted that the public hated the trusts fervently.”45

Elected state and federal officials channeled this popular anger into legislative action.46 Iowa was first out of the gate. In April 1888, its legislature adopted an “Act for the Punishment of Pools, Trusts and Conspiracies.”47 At their national conventions that summer, for the first time, both the Democratic and Republican platforms included antitrust policy planks.48 The Republicans declared their

opposition to all combinations of capital, organized in trusts or otherwise, to control arbitrarily the condition of trade among our citizens; and . . . recommend[ed] to Congress and the state legislatures, in their respective jurisdictions, such legislation as will prevent the execution of all schemes to oppress the people by undue charges on their supplies, or by unjust rates for the transportation of their products to market.49

That year, the Republican Convention nominated for president a compromise candidate, Benjamin Harrison, over the early front-runner, Senator Sherman of Ohio.50 One month after his defeat, Sherman successfully asked the Senate to give the Senate Finance Committee, of which Sherman was the former chairman and a leading member,51 jurisdiction over all bills dealing with the regulation of the “arrangements, contracts, agreements, trusts, or combinations . . . which tend to prevent free and full competition.”52

Efforts to craft a federal antitrust law began in earnest, and two early bills set the initial framework of the debate. Senator John Reagan, a Democrat from Texas, introduced the first bill on August 14, 1888. Reagan’s bill defined “trust” as

the combination of capital or skill by two more persons for the following purposes:

First. To create or carry out restrictions in trade.

Second. To limit, to reduce, or to increase the production or prices of merchandise or commodities.

Third. To prevent competition in the manufacture, making, sale, or purchase of merchandise or commodities.

Fourth. To create a monopoly.53

Reagan’s bill made engaging in trust activities a “high misdemeanor” subject to a ten-thousand-dollar fine and five years of imprisonment. It also included a jurisdictional provision that implicitly invoked Congress’s interstate and foreign Commerce Clause powers.54

Sherman prevailed in having Reagan’s bill referred to the Finance Committee, and then introduced his own.55 Sherman’s bill prohibited

all arrangements, contracts, agreements, trusts, or combinations . . . made with a view, or which tend, to prevent full and free competition in the production, manufacture, or sale of articles . . . and all arrangements, contracts, agreements, trusts, or combinations . . . designed, or which tend, to advance the cost to the consumer of any of such articles . . . .56

Sherman’s bill did not criminalize these combinations; instead, it called for the forfeiture of the charter of any corporate participant in a trust.57 But it was far from clear that Congress could strip a corporation of its state corporate charter. This defect, and the bill’s failure to include any reference to a constitutional grant of power, Hans Thorelli notes, made Sherman’s bill seem “a little amateurish” when compared with Reagan’s.58

In September, the Finance Committee reported out a version of Sherman’s bill that incorporated the criminalization and jurisdictional provisions of Reagan’s bill, but preserved Sherman’s operational language referring to “arrangements, contracts, agreements, trusts, or combinations” designed or tending to restrict competition or raise costs for consumers.59 The Fiftieth Congress then adjourned in March 1889.60

At the same time, state legislatures around the country convened for their 1889 legislative sessions and enacted a battery of state antitrust laws. Between March and July, eight states—Kansas, Maine, North Carolina, Nebraska, Texas, Tennessee, Missouri, and Michigan—approved antitrust statutes.61 Close on the heels of those statutes, in the summer and fall of 1889, a set of territories in the far West—North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, and Washington—gathered delegates to draft constitutions in anticipation of impending statehood. All the constitutional conventions except South Dakota’s chose to write antitrust provisions into their first state constitutions.62 The language of these statutes and constitutional provisions tracked the development of a national conversation on how to define and prohibit “trusts,” both within and among the states, and between the states and Congress.

Among the state statutes, two contained language similar to that used in Sherman’s and Reagan’s bills in Congress. Kansas’s law, passed on March 2, 1889, borrowed much of the language of Sherman’s operative provision prohibiting “arrangements, contracts, agreements, trusts or combination” tending to “prevent full and free competition” or tending to “advance, reduce or control the price or the cost to the producer or to the consumer.”63 At the end of March, Texas’s legislature adopted a law that copied Reagan’s operative definition of “trust”64 with a few changes, including the removal of any reference to “monopoly,” and the addition of a long and unwieldy catch-all provision.65 The Texas Legislature’s deference to Reagan’s conceptualization of the antitrust problem is unsurprising given that, in this pre-Seventeenth Amendment era, the legislature had elected Reagan to his Senate seat.66 The relationship worked the other way, too: in the spring of 1890, Reagan returned to Washington with a new bill that reflected the revisions worked in Austin during the state legislature’s 1889 session.67 While Kansas and Texas recycled Congress’s approaches, other states and territories experimented with new language.

This Part highlights four developments in the states that anticipated legislative developments in Congress. First, most states omitted any references to the impairment of “full and free competition,” or any similarly broad “competition” language. Instead, they chose to define trusts by reference to particular effects on the price and supply of particular articles of commerce.68 Second, most of the states wrote a mens rearequirement into their laws. It was not enough that a cartel or trust had the effect of raising prices; a “trust” was a combination formed with the purpose or intent of harming consumers.69 Third, a bloc of Midwestern states—Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska—broke up their operative antitrust provisions into two pieces. The first section essentially prohibited horizontal price-fixing arrangements.70 The second section prohibited placement of “the management or control” of a combination “in the hands of any trustee or trustees” with a view to fixing prices or restricting output—a prototype of the prohibition on monopoly that would emerge in the final version of the Sherman Act.71 Lastly, two states—Michigan and Texas—included exceptions for farmers or laborers.72

When the Fifty-First Congress returned to consider antitrust legislation in December 1889, three major antitrust bills were introduced. The first, Sherman’s, took substantially the same form as it had at the end of the Fiftieth Congress.73 Reagan also reintroduced his own bill with changes to the operative “trust” definition that reflected alterations made by the Texas Legislature the previous spring.74 A third bill, introduced by Senator James George, a Democrat from Mississippi, retained Sherman’s operative definition of “trust,” but followed the lead of the Michigan and Texas legislatures by adding a special proviso that excepted farmers and laborers from liability.75

In January 1890, the Finance Committee reported out an amended version of Sherman’s bill that criminalized only those arrangements made “with the intention to prevent full and free competition” or to raise prices, mirroring the movement in the states toward the inclusion of a statutory mens rea requirement.76 Senator George blasted this change, alleging that under the proposed language, it would be “impossible . . . to produce a conviction” for violation of the law.77 Sherman agreed with this critique, and two months later proposed an amendment to the bill that would eliminate the mens rearequirement and prohibit all combinations entered “with a view or which tend to prevent full and free competition” or “advance the cost to the consumer.”78 In a brief exchange with George on the Senate floor in March, Sherman disavowed the Committee’s mens realanguage and insisted that even a “tendency” to stifle competition would make a combination illegal, though not criminal: “The ‘intention’ can not be proved, though ‘tendency’ can. The tendency is the test of legality. The intention is the test of a crime.”79 No more was heard of the law’s mens rearequirement in Senate debate.80

The other principal elements of the nationwide antitrust movement showed up in the compromise Senate bill that emerged in late March. Rather than selecting one of the Sherman, Reagan, or George bills, the Senate picked all three: it kept Sherman’s provisions for civil liability, adopted Reagan’s definition of “trust,” taken from the Texas law, and his provisions for criminal antitrust liability,81 and incorporated George’s proviso shielding farmers and laborers from liability, taken from Texas and Michigan.82

Meanwhile, the legislative effort in the states continued. The winter and spring of 1890 saw the adoption of new antitrust statutes in three more states: Mississippi, South Dakota, and North Dakota. These three states split in their approaches to state antitrust regulation in ways that mirrored the debate in Congress. In late February, Mississippi’s legislature—breaking from the approach favored by its own Senator George—adopted a state antitrust statute that copied Texas’s statute and Reagan’s proposal in Congress.83 Just two weeks later, South Dakota’s state legislature adopted an antitrust statute that bore a strong resemblance to the Sherman formulation, referring to combinations preventing “free, fair and full competition” and combinations that “ten[d] to advance the price” of certain commodities and consumer goods.84 Meanwhile, the North Dakota Legislature chose a more laconic enactment that tracked Missouri’s statute and the constitutional provisions of the new Western states.85 Like several other Midwestern and Plains states, North Dakota also split its antitrust statute into two parts. The first section dealt with horizontal price-fixing agreements, and the second dealt with conspiracies to put the “management or control” of a combination in restraint of trade in a monopolistic entity.86

Back in Congress, the federal antitrust legislation took a sharp turn on March 27 when the provision-laden compromise bill that had taken shape two days earlier was, by a narrow thirty-one to twenty-eight vote, referred to the Judiciary Committee with instructions to return a polished bill within twenty days.87

The Judiciary Committee, led by Senator Edmunds, a Republican from Vermont, returned a bill that had been stripped down to its essentials.88 This version removed a raft of futures regulations introduced by Senator John James Ingalls, a Republican from Kansas,89 as well as the George proviso for farmers and laborers. It followed the Reagan bill by explicitly premising itself on Congress’s Commerce Clause authority,90 and drew from the Reagan and the Sherman bills in imposing both criminal and civil liability on antitrust violators.91

Yet the bill’s operational provisions, which defined the scope of prohibited combinations, resembled more the emerging consensus among state legislatures than the bills previously advanced in Congress. The bill followed the lead of Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, and North Dakota in splitting its major liability provisions into a horizontal-restraint-of-trade provision (the first section),92 and a provision prohibiting any person from attempting to control a trade or industry (the second section).93 The Edmunds bill removed all references to restraints on “free competition” and referred more simply to restraints on “commerce” and “trade or commerce.”94 The bill thus echoed state statutory and constitutional provisions that prohibited restraints on “any article of merchandise or commodity,”95 or on “any article of manufacture or commerce.”96

The Senate and House approved this simplified bill, which went to conference committee in mid-May.97 In the meantime, Kentucky passed the last pre-Sherman Act state antitrust statute.98 Its terms were copied from those contained in North Dakota’s and Missouri’s statutes, and it split the operative provisions into two parts (horizontal price-fixing and monopolization), limiting their prohibitions to restraints on “any article of property, commodity, or merchandise.”99

In June 1890, both houses of Congress approved the bill, and President Harrison signed it into law on July 2.100 Three days later, the Louisiana Legislature passed an antitrust statute of its own, whose operative provisions largely mirrored the language of the new federal law.101 With the federal legislation complete, the conversation between Congress and the states subsided.102

B. Federal-State Jurisdiction and the Sherman Act

The legislative history of the Sherman Act shows not only that its drafters were influenced by the same trends prevailing in the states, but also that federal lawmakers used state law as their template. Congress intended for the federal antitrust statute to provide federal jurisdiction over interstate combinations that state laws could not reach. Debate in Congress did not focus closely on the question of how to define trusts. That matter appears to have been among the least contentious of the issues facing the Fiftieth Congress and Fifty-First Congress.103 Senators of different ideological stripes and members of the House of Representatives saw that state and federal legislation would need to work hand in hand to defeat the trusts.104 The Sherman Act was meant to federalize the prohibitions that had already been enacted at the state level.105

Most of the Senate debate therefore addressed (1) the source of constitutional authority for congressional action and (2) the proper remedy. On the former question, members of the Senate sought to ground the new antitrust legislation in Congress’s Article I interstate commerce power,106 its Article I taxing power,107 or its Article III power to define and prescribe rules for federal courts’ exercise of jurisdiction.108 The question of Congress’s constitutional authority was tightly connected to its remedial power. Senator Reagan’s assertion of Commerce Clause authority, for instance, allowed him to propose criminal sanctions for trust violators.109 For Democratic Senator George and Democratic Senator George Vest, who questioned Congress’s power to prohibit trusts under the Commerce Clause,110 the alternative invocation of Congress’s power to lay and collect taxes and import duties provided an attractive remedy: opening up the trusts to foreign competition by stripping them of tariff protection (a major Democratic policy goal at the time).111 The major policy implications of the constitutional and remedial questions ensured that these issues received the lion’s share of contentious debate in the Senate.112

By contrast, on the question of how “trusts” would be defined—that is, what kinds of combinations or agreements would be unlawful—there was a strong consensus in the Senate that the federal antitrust law would render illegal those same combinations prohibited by state law. Senator Sherman described the complementary relationship between the federal law and state laws:

This bill, as I would have it, has for its single object to invoke the aid of the courts of the United States to . . . supplement the enforcement of the established rules of the common and statute law by the courts of the several States in dealing with combinations that affect injuriously the industrial liberty of the citizens of these States. It is to arm the Federal courts within the limits of their constitutional power that they may co-operate with the State courts in checking, curbing, and controlling the most dangerous combinations that now threaten the business, property, and trade of the people of the United States.113

The purpose of the law, then, was to take the law of the states and apply it federally, so that interstate combinations could not escape the regulation of state legislatures and courts, whose powers over out-of-state corporations were limited at that time by the dormant Commerce Clause114 and the territorial restrictions of personal jurisdiction under the rule of Pennoyer v. Neff.115

Sherman characterized these limitations on state power as the spur for federal action:

Similar contracts in any State in the Union are now, by common or statute law, null and void. Each State can and does prevent and control combinations within the limit of the State. This we do not propose to interfere with. The power of the State courts has been repeatedly exercised to set aside such combinations as I shall hereafter show, but these courts are limited in their jurisdiction to the State, and, in our complex system of government, are admitted to be unable to deal with the great evil that now threatens us.116

According to Sherman, the new law would set up a state-federal jurisdictional division of labor: “If the combination is confined to a State the State should apply the remedy; if it is interstate and controls any production in many States, Congress must apply the remedy.”117 For this dual jurisdiction, the same rules would apply. Sherman explained that the federal law “will enable the courts of the United States to restrain, limit, and control such combinations as interfere injuriously with our foreign and interstate commerce, to the same extent that the State courts habitually control such combinations as interfere with the commerce of a State.”118

Senator Vest of Missouri, who objected to Sherman’s proposal on constitutional grounds, going so far as to question Sherman’s capacity as a lawyer,119 nevertheless agreed with him about the basic structure of federal antitrust law. It would provide a remedy that would incorporate and fill in the gaps of state antitrust law:

I believe there is a remedy if you take the jurisdiction of the State and also the jurisdiction of Congress and put them together, but I do not believe there is any complete remedy in the action of either separately . . . .

. . . .

. . . I do not think there is any difficulty whatever as to that class of cases in which the products, or the transactions, to speak more accurately, take place entirely within the limits of a State; but we know that these trusts evade the State statutes even when they are made . . . .120

And Senator Reagan told his colleagues that whatever federal legislation they crafted would supplement a national antitrust regime established primarily in the states:

[I]f the people of this country expect salutary relief on this subject they must look to their State governments, for they have jurisdiction over the great mass of transactions out of which these troubles grow. If the Federal Government will act upon those things which relate to international and interstate commerce, and the States, responding to the necessity of the country and the complaints of the people, will act upon the branch of subjects of which the States have jurisdiction, we may, it seems to me, arrest the evil of trusts and combinations . . . .121

This understanding of the law’s purpose and meaning was also adopted and articulated by the House of Representatives. The House Judiciary Committee’s report on the bill to the full House carefully explained that the bill was designed to complement, not supplant, state law:

No attempt is made to invade the legislative authority of the several States or even to occupy doubtful grounds. No system of laws can be devised by Congress alone which would effectually protect the people of the United States against the evils and oppression of trusts and monopolies. Congress has no authority to deal, generally, with the subject within the States, and the States have no authority to legislate in respect of commerce between the several States or with foreign nations.

It follows, therefore, that the legislative authority of Congress and that of the several States must be exerted to secure the suppression of restraints upon trade and monopolies. Whatever legislation Congress may enact on this subject, within the limits of its authority, will prove of little value unless the States shall supplement it by such auxiliary and proper legislation as may be within their legislative authority.122

Such statements indicate that, in enacting the Sherman Act, Congress saw itself as establishing a federal antitrust jurisdiction that was only one part of a coherent national regulatory system, rooted in the “established rules of the common and statute law” of the states.123 This “integrated scheme” of regulation presents a classic in pari materia case for intertextual statutory interpretation.124 The states’ statutory declarations of policy thus form the essential backdrop for understanding the federal law’s broad prohibition on monopolies and arrangements “in restraint of trade or commerce.”125

II. the states’ consumer-welfare policy

With the Sherman Act, Congress committed the federal government to a national program of trust regulation first initiated in the states. This Part identifies the states’ antitrust policy by examining the text of the states’ antitrust legislation.

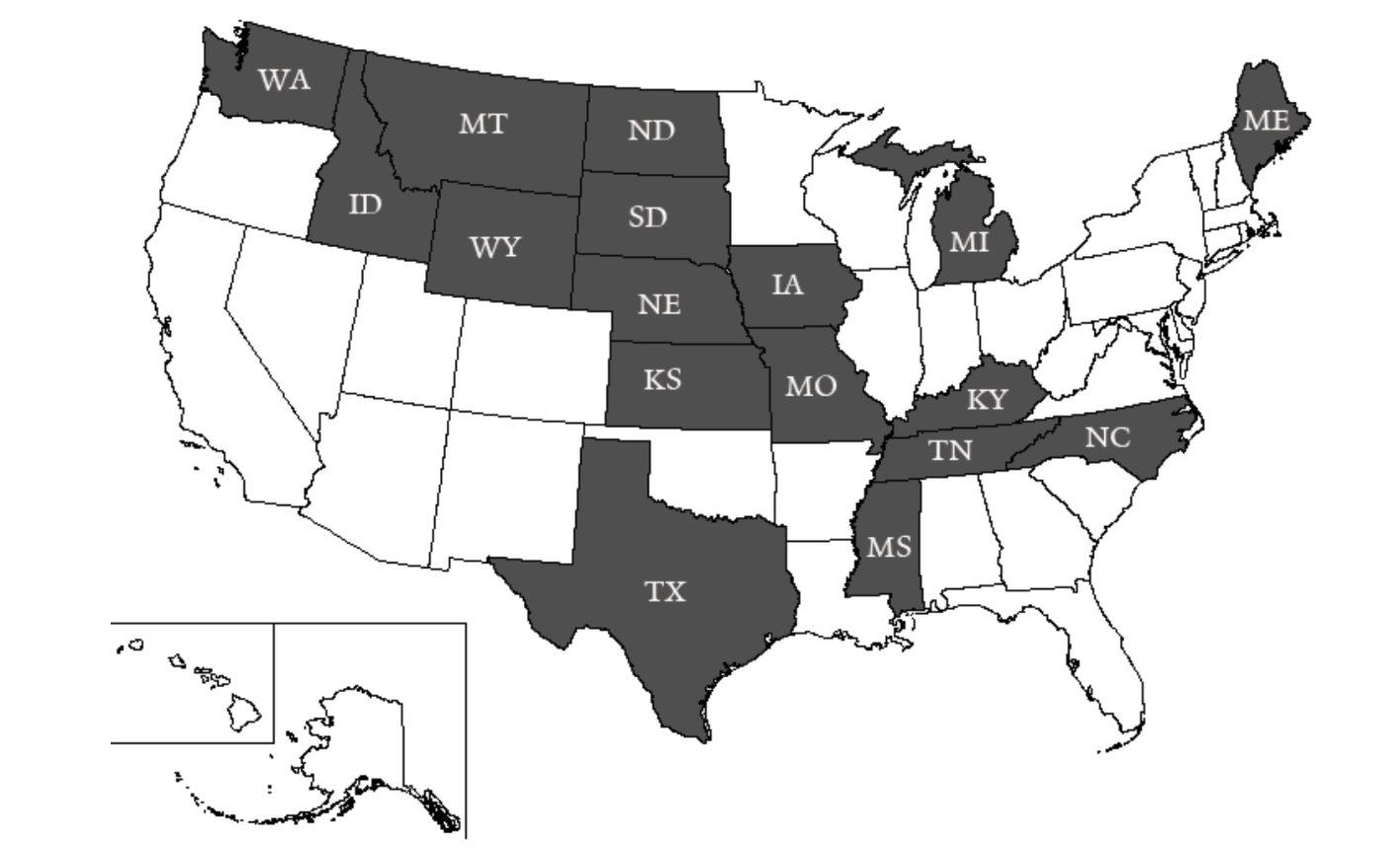

Popular frustration with trusts was not evenly distributed across the United States. Figure 1 displays a map of states that adopted state antitrust statutes or constitutional provisions prior to the signing of the Sherman Act in July 1890.

Figure 1.

state antitrust legislation before the sherman act126

As Figure 1 illustrates, early state antitrust legislation was a regional phenomenon that occurred principally in the Midwest and Plains states and the newly created states of the Mountain West and Pacific Northwest. Several states of the old Confederacy also enacted early antitrust legislation. Maine was the sole New England state to pass antitrust legislation, and the Mid-Atlantic region was not represented.

This pattern of legislative adoption across predominantly agricultural states is consistent with most historical accounts, which typically credit populist farmers and their interest groups—among them, The Grange and the Farmers’ Alliance—with sowing the seeds of antitrust policy in the late nineteenth century.127 These same historical accounts sometimes suggest that the populists pushing the development of state antitrust legislation intended for such legislation to serve as a protectionist bulwark against out-of-state corporations. This view of state antitrust legislation, which draws upon broad readings of economic and social history,credits state laws as flexible tools for “restor[ing] the balance of economic power” writ large.128 In other words, antitrust legislation was not so much a regime to protect consumers as an effort by small businessmen and farmers to wring profits out of powerful corporate competitors and suppliers.129

This Note departs from past approaches by examining the contents of the state antitrust statutes themselves. By and large, the statutory language does not support the view that the agricultural states of the South and West adopted antitrust legislation as protectionist or as “anti-bigness” weapons against the advances of powerful corporations. The prairie populists—or at least the pieces of legislation they enacted—were doing something else: they were prohibiting only those combinations and business practices that harmed consumers through restrictions on the production of a given commodity or article of commerce. In other words, they were working toward a policy of consumer welfare.

Before examining the language of the statutes, a brief explanation of “consumer welfare”—a term subject to some dispute130 in the antitrust community today—is required. This Note adopts Herbert Hovenkamp’s definition of consumer welfare, which is based on his observation of the policy of American antitrust regulators and courts: “[A]ntitrust policy in the United States follows a consumer welfare approach in that it condemns restraints that actually result in monopoly output reductions, whether or not there are offsetting efficiencies and regardless of their size.”131 Under this definition, consumer welfare refers to the preservation of consumer surplus generated under conditions of allocative efficiency, in which the price of an article of commerce is determined by its marginal cost of production. Prices and output in a market characterized by allocative efficiency are Pareto optimal, which means that any contrary allocation of resources would end up harming one or more market participants.

What does allocative efficiency look like? The outline is a familiar one. Consider a retail automotive market for sedans. Under ideal conditions, carmakers like Ford or Volkswagen will seek to maximize profits by making and selling as many of these cars as possible. They will make sedans until they can no longer profit from sales—that is, until the price of the last vehicle sold equals the marginal cost of its production (marginal cost). Consumers will purchase the sedans so long as the value consumers derive from them (marginal benefit) is greater than or equal to the purchase price. The price is set where marginal benefit equals marginal cost, so that the maximum number of sedans is produced at the lowest possible price. This price and output level is allocatively efficient and Pareto optimal because, without a change in the supply or demand curves, neither the carmakers’ profits (“producer surplus”) nor the consumers’ value-for-money (“consumer surplus”) can be increased without decreasing the other.

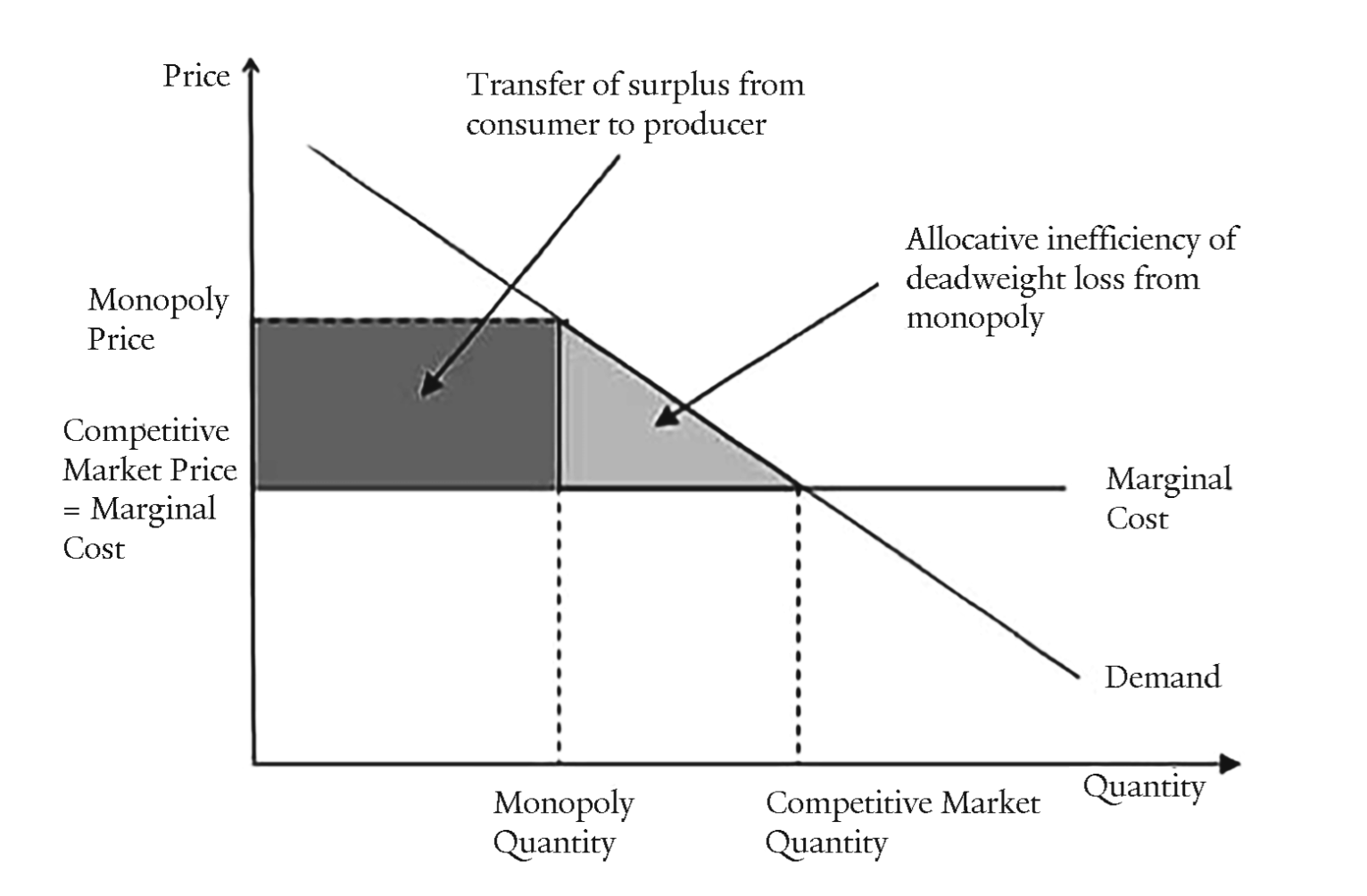

As Hovenkamp explains, antitrust policy in the United States follows a “consumer welfare” approach in that it condemns “monopoly output reductions”—that is, instances where a producer (or group of producers) with sufficient market power to set overall market output has decreased output to increase producer surplus.132 This increase in producer surplus comes at the expense of consumer surplus, since consumers must pay above-market prices. It also creates “deadweight loss,” or the destruction of wealth that would have been created for consumers andproducers if output remained at the Pareto-optimal level. The welfare consequences of allocative inefficiency in a monopoly market are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

welfare consequences of monopoly output reduction133

Simply put, a consumer-welfare policy aims to preserve consumer surplus by prohibiting these reductions of output. This is the policy of antitrust law in the United States today, and, as this Part argues, it was the antitrust policy adopted by state legislatures across the country from 1888 to 1890.

Consider Missouri’s antitrust statute,134 which bore a close resemblance to several of the pre-Sherman Act state antitrust measures.135 A full reproduction of its operative provisions conveys the statute’s purposes:

Section 1. If any corporation organized under the laws of this or any other state or country, for transacting or conducting any kind of business in this state, or any partnership or individual or other association of persons whosoever, shall create, enter into, become a member of or a party to any pool, trust, agreement, combination, confederation or understanding with any other corporation, partnership, individual, or any other person or association of persons, to regulate or fix the price of any article of merchandise or commodity, or shall enter into, become a member of or a party to any pool, agreement, contract, combination or confederation to fix or limit the amount or quantity of any article, commodity or merchandise, to be manufactured, mined, produced or sold in this state, shall be deemed and adjudged guilty of a conspiracy to defraud, and be subject to indictment and punishment as provided in this act.

Sec. 2. It shall not be lawful for any corporation to issue or to own trust certificates, or for any corporation, agent, officer or employes [sic], or the directors or stockholders of any corporation, to enter into any combination, contract or agreement with any person or persons, corporation or corporations, or with any stockholder or director thereof, the purpose and effect of which combination, contract or agreement shall be to place the management or control of such combination or combinations, or the manufactured product thereof, in the hands of any trustee or trustees, with the intent to limit or fix the price or lessen the production and sale of any article of commerce, use or consumption, or to prevent, restrict or diminish the manufacture or output of any such article.136

Reduced to its critical language, section 1 of the Missouri law prohibited any “agreement . . . to regulate or fix the price of any article of merchandise or commodity, or . . . to fix or limit the amount or quantity of any article, commodity or merchandise, to be manufactured, mined, produced or sold in this state.” Section 2 of the law prohibited monopolization, just like section 2 of the Sherman Act.137 Though the statute does not use the word “monopoly,” the language of the statute unambiguously refers to activities that we would now call monopolistic.138 It also uses the language of “trusts,” which then connoted a meaning we would now understand as synonymous with monopolies.139 A single business organization and its agents could be liable under section 2 where the organization was structured “with the intent to limit or fix the price or lessen the production and sale of any article of commerce, use or consumption, or to prevent, restrict or diminish the manufacture or output of any such article.”140

Three conclusions may be drawn from the face of this statute’s definition of liability for conspiracies in restraint of trade. First, agreements and combinations that did not reduce output and raise prices did not run afoul of the law. Second, Missouri lawmakers cared about price and output effects on particularcommodities and articles of merchandise, not overall social output or price effects. Third, under the antimonopoly provision of section 2, a business organization had to act with “the intent” to control output or prices. Monopolies achieved through productive efficiency, without any intention of controlling prices or output, did not violate the terms of the statute.

As explained below, each of these three basic features turned up in a majority of the states’ antitrust statutes or constitutional provisions. Together, they formed the states’ original consumer-welfare policy at the time of the Sherman Act’s adoption.

A. Prohibition of Restraints on Output and Prices

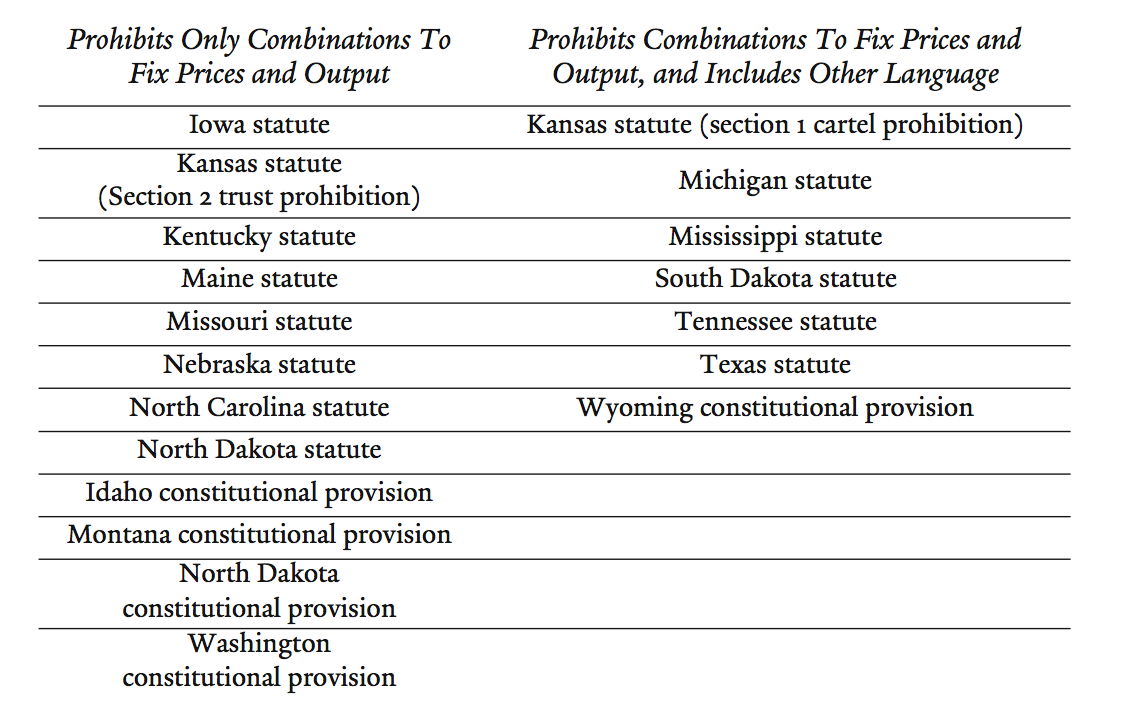

At the heart of most of the states’ antitrust enactments were concrete, specific definitions of antitrust liability. Table 1 shows the state-by-state breakdown of approaches on the first prong of the states’ consumer-welfare policy: a textual focus on price and output controls.

Table 1.

reference to price and output restraints141

As Table 1 illustrates, a majority of the state enactments prohibiting trusts and other conspiracies in trade referred onlyto conspiracies to “fix or limit the amount or quantity” of production and to “regulate or fix the price” of consumer goods. These legislatures and constitutional conventions understood the connection between supply and demand, and the terms of the statutes reflect a policy of promoting allocative efficiency.

Consider North Carolina’s antitrust statute, which defined “trust” in these terms:

[A]n arrangement, understanding or agreement, either private or public . . . for the purpose of increasing or reducing the price of the shares of stock of any company or corporation, or of any class of products, materials or manufactured articles, beyond the price that would be fixed by the natural demand for or the supply of such shares, products, materials or manufactured articles . . . .142

This understanding of “trusts” and their harms was shared across the continent in the emerging states of the far West, whose entry into the Union realigned American politics by facilitating a rural coalition of Southern and Western states capable of sustaining a “rising tide of Populism.”143 The depth of antitrust feeling in this region was such that the states chose to write antitrust provisions into their first state constitutions.144 But they adopted an antitrust framework that reflected the same policy principle articulated in Missouri and North Carolina. Constitutional delegates in Washington, Idaho, Montana, and North Dakota condemned only those agreements that had the effect of raising consumer prices through restrictions on output.145 Typical among these was the Montana Constitution, which provided:

No incorporation, stock company, person or association of persons in the state of Montana, shall directly, or indirectly, combine or form what is known as a trust, or make any contract with any person or persons, corporation, or stock company, foreign or domestic, through their stockholders, trustees, or in any manner whatever, for the purpose of fixing the price, or regulating the production of any article of commerce, or of the product of the soil, for consumption by the people.146

Even in states where antitrust legislation departed from the easily comprehensible formulations offered by the likes of Missouri, North Carolina, and Montana, antitrust laws targeted conspiracies to reduce output. Nebraska, for instance, adopted a two-part statute that resembled the final version of the Sherman Act: its first section prohibited cartel arrangements in which “a common price shall be fixed for any . . . article or product, or whereby the manufacture or sale thereof shall be limited”;147 its second section prohibited “[p]ooling . . . in the nature of what are commonly called trusts, for any purpose whatever,” without defining the kind of behavior that constituted a trust.148 But reference to contemporary sources makes clear that what was “commonly called” a trust in this era—an “organization formed mainly for the purpose of regulating the supply and price of commodities”149—was understood as the same kind of output-restricting combination condemned by Nebraska’s neighbors, Missouri150 and Iowa.151

A sizeable minority of states adopted provisions with more general principles, in addition to price-fixing output restrictions. Michigan’s antitrust statute, for example, prohibited combinations

the purpose or object or intent of which shall be to limit, control, or in any manner to restrict or regulate the amount of production or the quantity of any article or commodity to be raised or produced by mining, manufacture, agriculture or any other branch of business or labor, or to enhance, control or regulate the market price thereof, or in any manner to prevent or restrict free competition in the production or sale of any such article or commodity.152

Though Michigan’s legislature did not hew narrowly to the language employed in other states, its only deviation from the formulaic recitation of market prices and output was a prohibition on combinations “prevent[ing] or restrict[ing] free competition in the production or sale” of a commodity.153 But the legislature’s invocation of this broad policy goal on the heels of specific and narrowly tailored criteria for liability is a classic instance where courts would apply the ejusdem generis canon, which provides, “Where general words follow specific words in a statutory enumeration, the general words are [usually] construed to embrace only objects similar in nature to those objects enumerated by the preceding specific words.”154 The same principle of construction would apply to the antitrust statutes of Tennessee155 and South Dakota,156 as well as the Wyoming Constitution’s antitrust provision,157 all of which combined specific references to price-fixing and output restrictions with broad, almost nonjusticiable appeals to “legitimate trade” and the “public good.”

Only three states—Kansas, Texas, and Mississippi—attempted to define a broader antitrust policy. These three stood outside the consensus policy of the other states, which limited antitrust liability to combinations designed to depress output and raise prices for consumers. Kansas, which promulgated a standard monopolization provision in section 2 of its antitrust statute,158 also crafted a broader prohibition in section 1 designed to protect consumers and producers from changes in price. It prohibited not only arrangements impairing “full and free competition,” but also all combinations “which tend to advance, reduce or control the price or the cost to the producer or to the consumer of any such products or articles.”159 It thus reached business organizations that lowered prices for consumers while hurting other producers or suppliers in the process, either through productive efficiency or through monopsony power.

Texas’s law (and Mississippi’s,160 which copied Texas’s operative definition nearly word for word) enacted similarly broad prohibitions. Its antitrust statute defined “trust” by way of five illegal purposes: first, to “create or carry out restrictions in trade”; second, to limit production or increase or reduce prices; third, to “prevent competition”; fourth, to fix prices “at any standard or figure”; and fifth, to enter into an “agreement of any kind . . . to pool, combine, or unite any interest . . . with the sale or transportation of any such article or commodity that its price might in any manner be affected.”161 Like the Kansas statute, Texas’s prohibition on combinations that had any effect on commodity prices could be used to punish businesses that succeeded in lowering consumer prices through new productive efficiencies. This was not a narrow consumer-protection statute; it was a legislative sledgehammer designed with what one scholar and one corporate lawyer called “an intent to terrify” big business.162

This “intent to terrify” is noteworthy because it was an outlier among the states’ antitrust policies. Texas’s unique approach is especially significant given that it was one of the early movers in state antitrust legislation. Ten of the eleven states163 (all except Mississippi) that adopted antitrust legislation after Texas but before the Sherman Act eschewed Texas’s wide-ranging prohibitions and followed the approach of Iowa and Missouri, proscribing only business arrangements that impaired allocative efficiency.

B. Reference to Particular Commodities and Articles of Commerce

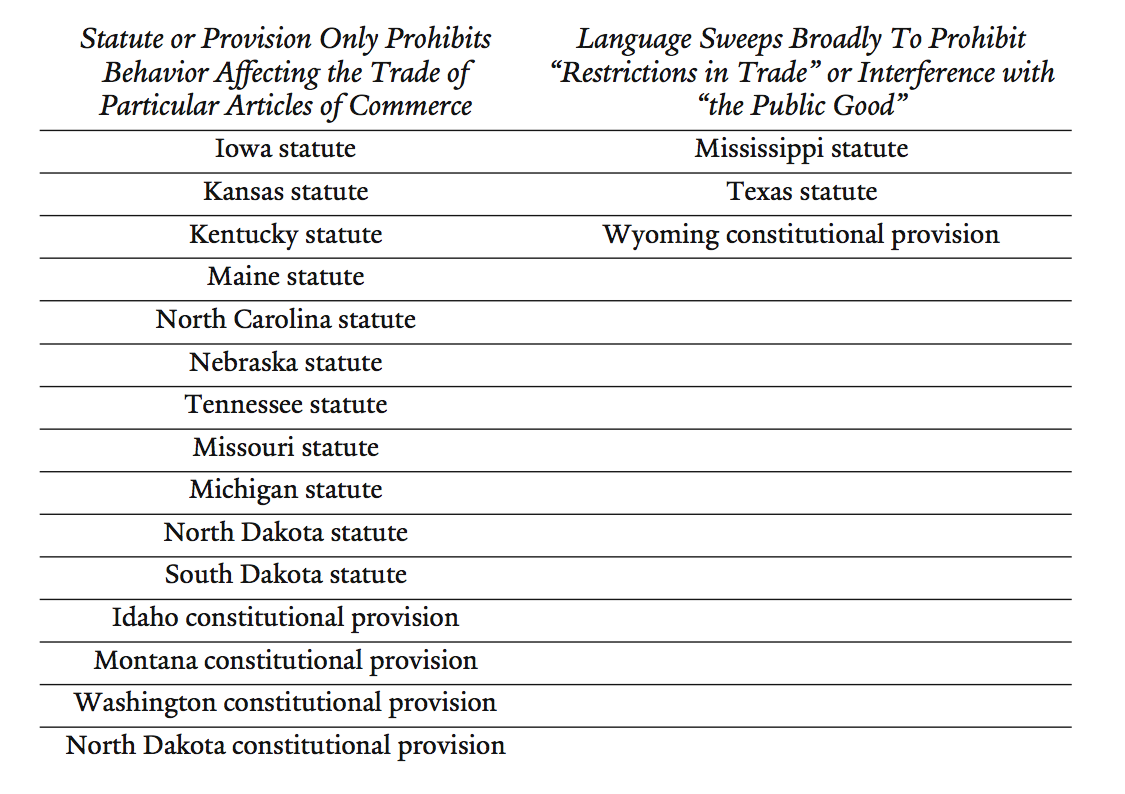

The second prong of the states’ consumer-welfare policy was its commitment to preserving allocative efficiency with respect to the production of particular commodities and articles of commerce. The state statutes sought to keep price and output in individual product markets at their natural, competitive level; they did not seek to maximize social welfare.164 Table 2 tracks the state statutes’ references to effects on particular commodities and articles of commerce. As Table 2 indicates, a majority of jurisdictions used legislative language focused on price and output effects for discrete classes of products.

Table 2.

reference to effects on particular articles of commerce165

Under this prong of the states’ original consumer-welfare policy, violators of the antitrust laws must have actually raised the prevailing price or lowered the total output of some particular “product of the soil or . . . article of manufacture or commerce,” as the North Dakota Constitution provided.166 Two state statutes even went so far as to provide nonexhaustive lists of such products: Iowa enumerated “oil, lumber, coal, grain, flour, provisions or any other commodity or article whatever”;167 South Dakota reeled off “farm machinery, implements, tools, supplies, and lumber, wood and coal,” and also referred specifically to product dumping in “wheat, corn, oats, barley, flax, cattle, sheep, hogs, or other farm or agricultural products.”168 Other states used more general terms, such as “the price of any merchandise,”169 or “any article or commodity to be raised or produced by mining, manufacture, agriculture or any other branch of business or labor,”170 or “any article of commerce, use, or consumption.”171 Even Michigan’s statute, which referred in broad terms to the impairment of “free competition,” referred to the restriction of such competition specifically “in the production or sale of any such article or commodity.”172

Here, too, Mississippi and Texas adopted statutes that diverged from the consensus policy: their definition of trust encompassed any “restrictions in trade,” without explicit textual regard to price effects on particular commodities or goods.173 But this broader language represented a minority position: the text of nearly every state antitrust law adopted a clearer standard for liability that was focused on price and output effects with regard to particular markets.

C. Mens Rea Requirement

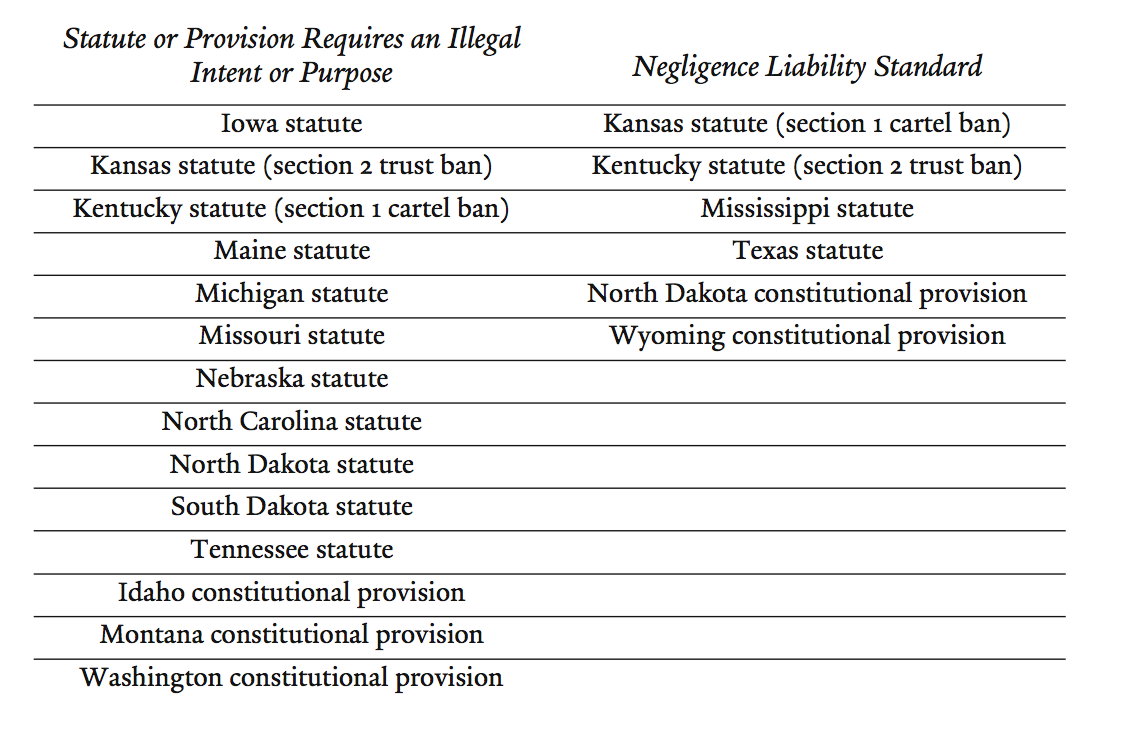

Lastly, a majority of state statutes and constitutional provisions prohibited only business practices that exhibited a purpose or intentto restrict output and control prices. Although several states criminalized or prohibited arrangements that merely resulted in a restriction on output, the bulk of states took a narrower approach. Table 3 lists the states’ liability standards for cartel and trust prohibitions.

Table 3.

mens rea standards174

North Carolina, for example, prohibited only those arrangements “entered into . . . for the purpose” of fixing prices.175 Michigan proscribed agreements with the “purpose or object or intent” to control output.176 Tennessee banned combinations “for the purpose of injuriously affecting the legitimate trade and commerce . . . or to limit the supply or production . . . for the purpose of speculation.”177 Three states—Kansas, Kentucky, and North Dakota—split their antitrust policies with regard to mens rea. Kansas’s prohibition on horizontal arrangements in restraint of trade covered all arrangements “made with a view or which tend to prevent . . . competition,”178 but its antimonopolization provision required “intent to . . . lessen the production” of an article of commerce.179 Kentucky did just the reverse, requiring proof of intent or purpose with respect to horizontal arrangements but imposing strict liability for the antimonopolization provision of the statute.180 The North Dakota Constitution prohibited any combination “having for its object or effect”181 the fixing of prices or production but limited criminal penalties in its statutory antitrust enactment to “agreement[s] . . . to regulate or fix” prices or output.182

North Dakota’s example is instructive. Except for the constitutional provisions, the states’ legislative antitrust enactments were criminalstatutes, so a consensus policy in favor of a mens rearequirement is unsurprising: the maxim that “[t]here can be no crime, large or small, without an evil mind”183 is an enduring principle of English and American law.184 Although several states chose to pursue the trusts more aggressively by making trust-like behavior a strict-liability crime, most states chose to follow a more traditional mens reaapproach in the criminal law governing the trusts.

III. applying the original consumer-welfare policy

When Congress enacted the Sherman Act, it borrowed a consumer-welfare policy from the states. That policy is the prevention of deadweight loss resulting from monopoly output reductions in individual markets for goods and services. Antitrust law should concern itself with no more than this, and no less. More pointedly, this approach entails navigating a middle course between the Scylla of a “total-welfare” model on one side, and the Charybdis of an ambiguous “competition” theory of antitrust on the other.

A. Rejection of Dueling Efficiencies and Williamson’s “Naïve Tradeoff”

Scholars have debated how courts ought to weigh conflicts between two kinds of efficiency: allocative efficiency and productive efficiency. As we have seen, allocative efficiency is a Pareto optimal market state in which the price for a given product is equal to its marginal cost, and under which consumer and producer surplus is maximized. Productive efficiency simply refers to a reduced marginal cost of production, and is associated with the kind of cost savings we commonly think of as “efficiency,” including reduced labor or overhead costs. In a market characterized by allocative efficiency, productive efficiencies are obviously good for consumers: when a producer realizes productive efficiency gains (as in Henry Ford’s assembly line), and reduces the marginal cost of its product (as with the Model T), those savings are passed along to consumers in the form of lower prices.

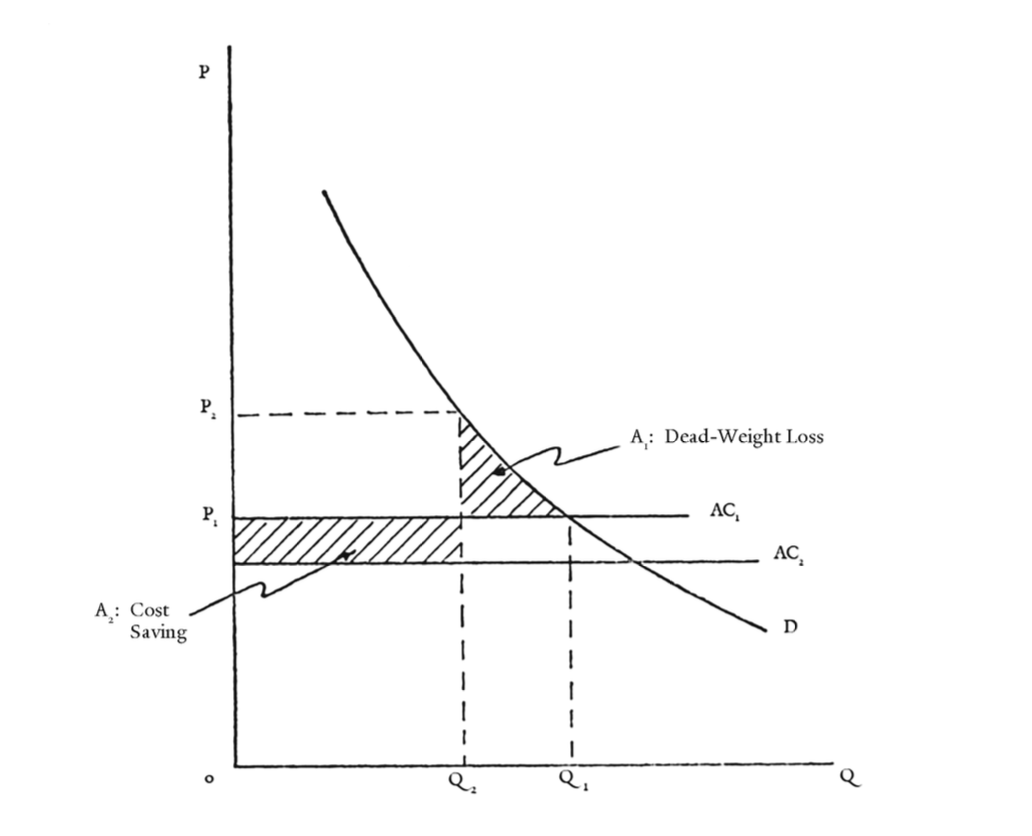

The problem is that productive efficiency does not always coincide with allocative efficiency. Consider the classic “naïve tradeoff” hypothetical posed nearly fifty years ago by Oliver Williamson, in which a court or regulator evaluates the legality of a horizontal merger between firms that creates productive efficiencies (reducing the cost of production), but gives the newly enlarged firm a sufficient command of the market to reduce output and raise prices for consumers, creating allocative inefficiency.185 This scenario is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

the naïve tradeoff186

Williamson and other proponents of a “total-welfare” theory of antitrust law asked courts and federal regulators to weigh the relative size of A1 (deadweight loss) and A2 (productive efficiencies) to determine whether the merger is illegal. According to Williamson, if the productive efficiencies outweighed the deadweight loss, regulators and courts should allow the firm to make an efficiency defense and avoid antitrust liability.187 Total-welfare theory reasons that this outcome maximizes social welfare: after all, those cost savings from productive efficiencies go somewhere (specifically, to firms and their shareholders) and free up resources for the production of other goods, enriching consumers overall.188 Under the total-welfare approach, regulators prioritize the wealth of all consumers, rather than that of consumers in a particular market (“consumer welfare” or “purchaser welfare”).189

As a policy option, the total-welfare model has much to recommend it. But it is inconsistent with the consumer-welfare policy adopted by the states and Congress between 1888 and 1890. As we saw in Part II, most state antitrust statutes narrowly condemned output restrictions on particular commodities or articles of commerce; they were not written to maximize overall social output.190 Under the original consumer-welfare standard, a court will not attempt to balance productive and allocative efficiencies: the demonstrated creation of an allocative inefficiency (deadweight loss) in a given market suffices to prohibit the combination.

The Supreme Court has not grappled with the total welfare theory since it explicitly adopted a consumer-welfare policy in Reiter v. Sonotone Corp.,191 and federal courts have resisted the “naïve tradeoff” offered by Williamson and other advocates of the total-welfare approach. Instead, courts have maintained consumer welfare (allocative efficiency) as the ultimate criterion of the antitrust laws. As Robert Pitofsky notes, “There is no recorded instance in the United States where an otherwise illegal merger was found by a court not to violate the antitrust laws because of the presence of [productive] efficiencies.”192 A representative example can be found in Judge Collyer’s opinion in Federal Trade Commission v. CCC Holdings, Inc.193 In that case, the trial court held that it would allow the introduction of productive efficiencies as a defense to liability only if there was concrete evidence that the benefits of such efficiencies would be passed on to consumers in the relevant market—that is, only if consumer welfare remained unharmed.194 The federal courts’ current approach to productive efficiencies presents a straightforward implementation of the original consumer-welfare policy.

B. Protecting Competition on Behalf of Consumers Alone

Notwithstanding federal courts’ steady application of a consumer-welfare policy, there remains a persistent call among antitrust scholars for its abandonment in favor of a broad procompetition policy said to be rooted in the original public understanding of the Sherman Act.195 Orbach, for instance, argues that antitrust law should be “nuanced, dynamic, and imperfect” and urges that Judge Hand’s approach be “reheard” so as to “preserve some degree of flexibility” in condemning business arrangements that harm competition, broadly defined.196 John Kirkwood advances a similar but narrower argument that antitrust ought to prohibit anticompetitive transfers of wealth, whether caused by buyers or sellers.197

The conflict between the pro-“competition” standard and the consumer-welfare standard arises neatly in the current debate over antitrust’s treatment of monopsonies, in which a single purchaser (or a group of purchasers) uses its market power to reduce the price paid to suppliers of a particular good. Kirkwood and Robert Lande argue that the antitrust laws should prohibit such “anticompetitive behavior by buyers.”198 The argument against monopsony was raised by some commentators in the lead-up to a failed merger attempt between Comcast and Time Warner Cable. Critics of the deal argued that even if the merger would not have disadvantaged consumers, it would have harmed the providers of television content (such as HBO or Disney) by giving an enlarged Comcast yet more leverage to negotiate low wholesale rates for programming. As one journalist wrote, “It would be hard to successfully make the case that their market power as sellers is pitted against consumers. Instead, the antitrust scrutiny at the Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission will likely center on . . . monopsony.”199 The merger was eventually scuttled under pressure from the Federal Communications Commission, which appears to have been principally concerned with a monopsony problem: that the new entity’s command of the broadband internet service market would allow it to squeeze streaming content providers, like Netflix.200

Yet under the original consumer-welfare standard discussed above, monopsony does not violate the antitrust laws unless evidence shows that monopsony inevitably leads to reduced output and higher prices for consumers.201 Just as productive efficiencies are ultimately irrelevant to antitrust liability unless they help to preserve consumer surplus, monopsonies are irrelevant to the enforcement of the antitrust laws unless they ultimately diminish consumer surplus. Put differently, the consumer-welfare standard is indifferent to the balance of interests between the likes of Comcast and Netflix unless that balance somehow diminishes the wealth of consumers.202

C. Narrowing the Applicability of Per Se Rules Under Section 1

The original consumer-welfare policy prohibited only those arrangements entered into with the “purpose” or “intent” of raising consumer prices and restricting output.203 This mens rearequirement is consistent with the Supreme Court’s conclusion in United States Gypsum Co. that intent to manipulate prices is an element that must be proved in every Sherman Act criminal prosecution.204 It also lends support to the argument that section 1 of the Sherman Act should not impose civil liability for per se prohibitions on business practices that do not necessarily harm consumer welfare, consistent with the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence over the past four decades.205 As the courts have recognized, some of these practices, formerly illegal per se, are entered into “not out of disinterested malice, but in . . . commercial self-interest” that is essentially procompetitive.206 The states’ mens rearequirement suggests that per se illegality under section 1 should be reserved for cartel-like agreements that are explicitly designed to restrict output or raise market prices—those agreements that are actually “formed for the purpose and with the effect” of hurting consumers.207 All other forms of agreement must be submitted to an analysis that takes intent into account, “not because a good intention will save an otherwise objectionable regulation or the reverse; but because knowledge of intent may help the court to interpret facts and to predict consequences.”208

Conclusion

The Sherman Act’s capacious language helps explain the pinball-like trajectory of American antitrust law over its long life, a life that has seen various governing principles come and go like so many changes in political fashion.209 For close to forty years, however, federal courts have increasingly embraced a single principle—consumer welfare—as antitrust’s guiding policy. This approach has brought coherence to the law, albeit dogged by lingering doubts about its pedigree: many continue to suspect that the consumer-welfare principle is just an expedient of the Chicago school of economics, a convenient way of rationalizing an otherwise opaque text.

Discerning the organizing policy of the Sherman Act would be much easier, of course, if Congress had laid out a more specific standard for liability in the text of the Sherman Act itself. But its failure to do so does not render the statute incomprehensible. If Congress meant anything by the Sherman Act, it meant to supplement the states’ early antitrust efforts—through case law and through legislation—with a federal statute that would impose antitrust liability at the interstate level to the same extent as state law did at the intrastate level. Congress may have punted in defining antitrust liability, but the states did not. Courts and scholars need not apologize for grafting a consumer-welfare policy onto the Sherman Act. Consumer welfare has been there since the beginning.

See Antitrust Div., Criminal Enforcement Fine and Jail Charts Through Fiscal Year 2014, U.S. Dep’t Just. (June 25, 2015), http://www.justice.gov/atr/criminal-enforcement-fine-and-jail-charts [http://perma.cc/HFA5-J9TT]; Antitrust Div., Sherman Act Violations Yielding a Corporate Fine of $10 Million or More, U.S. Dep’t Just. (Apr. 22, 2015), http://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2015/04/23/sherman10.pdf [http://perma.cc/VB5P-59AY].

Frank H. Easterbrook, Workable Antitrust Policy, 84 Mich. L. Rev. 1696, 1705 (1986); cf. Andrew S. Oldham, Sherman’s March (in)to the Sea, 74 Tenn. L. Rev. 319, 325 (2007) (arguing that common-law judicial interpretation has “unmoored the Sherman Act from its statutory foundations and set it adrift in a stormy sea of illegitimacy”).

See, e.g., Summit Health, Ltd. v. Pinhas, 500 U.S. 322, 328 n.7 (1991); Associated Gen. Contractors of Cal., Inc. v. Cal. State Council of Carpenters, 459 U.S. 519, 531 (1983); Apex Hosiery Co. v. Leader, 310 U.S. 469, 489 (1940); Standard Oil Co. of N.J. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1, 50 (1911); Hamilton Chapter of Alpha Delta Phi, Inc. v. Hamilton Coll., 128 F.3d 59, 63-64 (2d Cir. 1997); McGahee v. N. Propane Gas Co., 858 F.2d 1487, 1497-98 (11th Cir. 1988); GTE Sylvania Inc. v. Cont’l T.V., Inc., 537 F.2d 980, 1019 & n.2 (9th Cir. 1976), aff’d, 433 U.S. 36 (1977); cf. Tex. Indus., Inc. v. Radcliff Materials, Inc., 451 U.S. 630, 644 (1981) (“It is very true that we use common-law terms here and common-law definitions in order to define an offense which is in itself comparatively new, but it is not a common-law jurisdiction that we are conferring upon the circuit courts of the United States.” (quoting 21 Cong. Rec. 3149 (1890) (statement of Sen. Morgan))).

See U.S. Const. art. I, § 1 (“All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States . . . .”); id. art. III, § 1 (“The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.”).

See Chicago Bd. of Trade v. United States, 246 U.S. 231, 238 (1918) (“[T]he legality of an agreement or regulation cannot be determined by so simple a test, as whether it restrains competition. Every agreement concerning trade, every regulation of trade, restrains. To bind, to restrain, is of their very essence.”).

See Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 133 S. Ct. 1351, 1363 (2013); Leegin Creative Leather Prods., Inc. v. PSKS, Inc., 551 U.S. 877, 906 (2007); Brooke Grp. Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 509 U.S. 209, 221 (1993); Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n v. Bd. of Regents of Univ. of Okla., 468 U.S. 85, 107 (1984).

See, e.g., Christopher Grandy, Original Intent and the Sherman Antitrust Act: A Re-Examination of the Consumer-Welfare Hypothesis, 53 J. Econ. Hist. 359 (1993); Thomas W. Hazlett, The Legislative History of the Sherman Act Re-Examined, 30 Econ. Inquiry 263 (1992); Robert H. Lande, The Rise and (Coming) Fall of Efficiency as the Ruler of Antitrust, 33 Antitrust Bull. 429, 451 n.81 (1988) (“Bork selectively interprets Congressional will to suit his own agenda; he does not defer to a Congress that had different goals.”). But see Daniel A. Crane, The Tempting of Antitrust: Robert Bork and the Goals of Antitrust Policy, 79 Antitrust L.J. 835, 840-44 (2014).

United States v. Freeman, 44 U.S. (3 How.) 556, 564 (1845); see United States v. Stewart, 311 U.S. 60, 64-65 (1940); William N. Eskridge, Jr. et al., Cases and Materials on Legislation 1066-81 (4th ed. 2007); William N. Eskridge, Jr., The New Textualism, 37 UCLA L. Rev. 621, 663 n.169 (1990); Abbe R. Gluck & Lisa Schultz Bressman, Statutory Interpretation from the Inside—an Empirical Study of Congressional Drafting, Delegation, and the Canons: Part I, 65 Stan. L. Rev. 901, 927 fig.1 (2013); Quintin Johnstone, An Evaluation of the Rules of Statutory Interpretation, 3 U. Kan. L. Rev. 1, 4 (1954) (“All courts make great use of statutes in pari materia . . . .”).

See, e.g., Moore v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., 291 U.S. 205, 214 (1934) (reading the Federal Safety Appliance Act in pari materia with an analogous Kentucky statute); Fed. Deposit Ins. Corp. v. Am. Bank Tr. Shares, Inc., 460 F. Supp. 549, 559-60 (D.S.C. 1978); Underwater Constr. v. Shirley, 884 P.2d 150, 155 (Alaska 1994); Wilson v. Freedom of Info. Comm’n, 435 A.2d 353, 359 (Conn. 1980); Bethlehem Steel v. Comm’r of Labor & Indus., 662 A.2d 256, 258 (Md. 1995); Powder River Basin Res. Council v. Wyo. Dep’t of Envtl. Quality, 2010 WY 25, ¶ 7, 226 P.3d 809, 813 (Wyo. 2010).

See, e.g., Alvord-Polk, Inc. v. F. Schumacher & Co., 37 F.3d 996, 1014 (3d Cir. 1994) (noting that the plaintiffs’ Pennsylvania-law antitrust claim “rises or falls with plaintiffs’ federal antitrust claims”); Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 269 F. Supp. 2d 1213, 1223-24 (C.D. Cal. 2003) (finding that construction of federal antitrust law should guide construction of state antitrust law because the state law “has objectives identical to the federal antitrust acts” (quoting Vinci v. Waste Mgmt., Inc., 36 Cal. App. 4th 1811, 1814 n.1 (Ct. App. 1995))); Stolow v. Greg Manning Auctions Inc., 258 F. Supp. 2d 236, 244 n.8 (S.D.N.Y. 2003); Verizon N.J., Inc. v. Ntegrity Telecontent Servs., Inc., 219 F. Supp. 2d 616, 632 (D.N.J. 2002); La. Power & Light Co. v. United Gas Pipe Line Co., 493 So. 2d 1149, 1158 (La. 1986) (“Because La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 51:122 is a counterpart to § 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act, the United States Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Sherman Act should be a persuasive influence on the interpretation of our own state enactment.”); Beville v. Curry, 2001 OK 1, ¶ 11, 39 P.3d 754, 759; H.J. Baker & Bros., Inc. v. Orgonics, Inc., 554 A.2d 196, 204 (R.I. 1989); Hovenkamp, supra note 26, at 377 n.10 (“[S]tate antitrust laws are substantively similar to federal antitrust law, and many state courts have held that case law interpreting the federal statutes is fully applicable to corresponding state statutes.”).

See, e.g., Field v. Mans, 516 U.S. 59, 72. n.10, 73-74, 73 nn.11-12 (1995) (consulting state-court definitions to determine the level of reliance required to constitute “actual fraud” under a provision of the federal Bankruptcy Code); Evans v. United States, 504 U.S. 255, 269 (1992) (consulting state-court definitions of “extortion” to clarify the meaning of “extortion” in the Hobbs Act).

See, e.g., Wayne D. Collins, Trusts and the Origins of Antitrust Legislation, 81 Fordham L. Rev. 2279, 2340 (2013) (noting that “backers of the Sherman Act assured the floor of the Senate that they were merely seeking to enable federal courts to apply the common law to anticompetitive business activities and early federal cases are full of citations to English and state common law”); William L. Letwin, Congress and the Sherman Antitrust Law: 1887-1890, 23 U. Chi. L. Rev. 221, 252-53 (1956) (noting Senator Sherman’s argument that the Sherman Act was meant to prohibit “all those [combinations] which the common law had always condemned as unlawful” and recalling Sherman’s reading of the Richardson v. Buhl decision on the floor of the Senate).

See, e.g., N. Sec. Co., 193 U.S. at 339 (“[W]hen Congress declared contracts, combinations and conspiracies in restraint of trade or commerce to be illegal, it did nothing more than apply to interstate commerce a rule that had been long applied by the several States when dealing with combinations that were in restraint of their domestic commerce.”).

See Idaho Const. art. XI, § 18 (1889); Mont. Const. art. XV, § 20 (1889); N.D. Const. art. VII, § 146 (1889); Wash. Const. art. XII, § 22 (1889); Wyo. Const. art. X, § 8 (1889); Act of Apr. 16, 1888, ch. 84, 1888 Iowa Acts 124; Act of Mar. 2, 1889, ch. 257, 1889 Kan. Sess. Laws 389; Act of May 20, 1890, ch. 1621, 1889 Ky. Acts 143; Act of Mar. 7, 1889, ch. 266, 1889 Me. Laws 235; Act of July 1, 1889, No. 225, 1889 Mich. Pub. Acts 331; Act of Feb. 22, 1890, ch. 36, 1890 Miss. Laws 55; Act of May 18, 1889, 1889 Mo. Laws 96; Act of Mar. 29, 1889, ch. 69, 1889 Neb. Laws 516; Act of Mar. 11, 1889, ch. 374, 1889 N.C. Sess. Laws 372; Act of Mar. 3, 1890, ch. 174, 1890 N.D. Laws 503; Act of Mar. 7, 1890, ch. 154, 1890 S.D. Sess. Laws 323; Act of Apr. 4, 1889, ch. 250, 1889 Tenn. Pub. Acts 475; Act of Mar. 30, 1889, ch. 117, 1889 Tex. Gen. Laws 141.

See David Millon, The First Antitrust Statute, 29 Washburn L.J. 141, 148 (1990) (“Most antitrust activity began not at the national level, but rather at the state and local level.” (quoting Steven L. Piott, The Anti-Monopoly Persuasion: Popular Resistance to the Rise of Big Business in the Midwest 4 (1985))).

Act of Mar. 2, 1889, ch. 257, 1889 Kan. Sess. Laws 389; Act of Mar. 7, 1889, ch. 266, 1889 Me. Laws 235; Act of July 1, 1889, No. 225, 1889 Mich. Pub. Acts 331; Act of May 18, 1889, 1889 Mo. Laws 96; Act of Mar. 29, 1889, ch. 69, 1889 Neb. Laws 516; Act of Mar. 11, 1889, ch. 374, 1889 N.C. Sess. Laws 372; Act of Apr. 4, 1889, ch. 250, 1889 Tenn. Pub. Acts 475; Act of Mar. 30, 1889, ch. 117, 1889 Tex. Gen. Laws 141.