Perfect Plaintiffs

Brown. Roe. Loving. These names evoke seminal Supreme Court decisions that instituted massive social and legal shifts.1 While it may not roll off the tongue quite as easily, Obergefell is poised to join this pantheon. Jim Obergefell and the twenty-nine other men and women named in Obergefell v. Hodges are among the most highly publicized plaintiffs in history. Thousands of videos, photographs, and articles tell their stories, emphasizing their ordinariness and approachability.2 In briefing and oral argument, attorneys described the couples’ commitment to each other and to their many children. The strategy: “Be normal.”3

Careful plaintiff selection undoubtedly played a key role in the ascent of marriage equality, particularly for a Court that has been acutely aware of public opinion and concerned about its historic legacy.4 A well-selected plaintiff can provide a concrete context for abstract legal concepts and personalize the stakes. Justice Kennedy, author of all the recent decisions expanding rights for gay people, has repeatedly expressed rights in terms of individual human dignity.5 Tellingly, Justice Kennedy outlines the story of three plaintiff couples near the start of the Obergefell opinion.6

As a former litigator for juvenile justice and education reform, I know well that the selection of plaintiffs is one of the most significant decisions a cause lawyer can make.7 The plaintiffs must be amenable to the spotlight and both sympathetic and relatable to the average person. Lawyers have historically denied that they cherry-pick appealing plaintiffs, perpetuating the myth that cases arrive at the Supreme Court by chance.8 Although some of the Obergefell attorneys framed the case as “happening totally by accident,” other accounts confirm that they selected and groomed their plaintiffs with great care.9

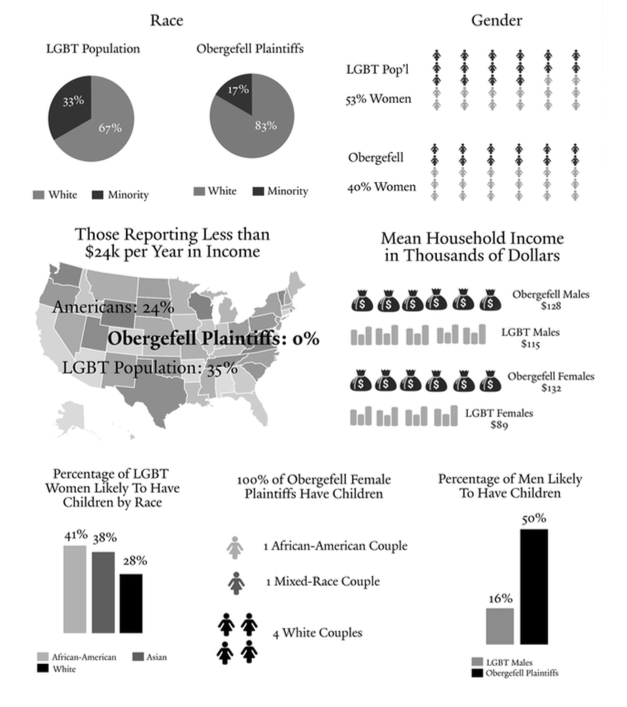

Typical is one couple—two attractive veterinary professors who were recruited because they are “in a stable, good relationship,” and are “likeable” “homeowners” with respectable jobs.10 The other plaintiffs are similarly TV-ready, sure to appeal to the public and Justices alike. None look butch, drag, or flamboyant. Four qualities make them generically appealing, especially to a predominantly straight audience: they are all-American; they seem to be asexual; many have children; and all are (purportedly) non-political. There are no outlaws here. Stonewall has become Stepford.11 This infographic12 illustrates the conformity at work:

Figure 1.

obergefell plaintiffs compared to lgbt population averages

Of course, the equality- and liberty-based claims for same-sex marriage do not depend on the identities of individual parties. Yet more information is offered to courts about the plaintiffs’ personal lives than their legal arguments.13 Why? Because the Supreme Court is mainstream in its own way, composed of nine individuals from a very narrow slice of the population. Skilled advocates “play by its rules, and tell the Justices stories they like to hear about people who remind them of themselves.”14 In other words, plaintiffs should assimilate to norms that the Justices understand and their lawyers should play down differences.15

This schema reveals some deep-rooted assumptions about what a family should look like and what is an appropriate path to social change. It also re-inscribes these norms and obscures the ways in which many families do not and have never fit this model. The public face of same-sex marriage, as represented by the Obergefell plaintiffs, does not accurately represent the realities of either gay (LGB) or straight households. It thus reflects a missed opportunity to celebrate the diversity—racial, economic, cultural, and lifestyle—of all families. Kenji Yoshinohas described the harms, both individual and social, of such “covering.”16 Building on this work, I argue that fronting straight-acting plaintiffs leaves intact the problematic traditional marital hegemony; squanders the potential of diversity to enrich all families; and risks perpetuating the harmful norms that LGB families and cultures are second-best.

This Essay begins by describing the plaintiffs in four historic intimacy cases—Loving, Roe, Lawrence and Windsor. Part II outlines the heteronormative and traditional characteristics present in the carefully curated set of Obergefell plaintiffs, contrasting them with the historic plaintiffs. Part III argues that there are perils to relying on the identities of individual, seemingly “ideal,” plaintiffs. Conforming to achieve civil rights brings significant costs.

A caveat is necessary. I am not contending that the lawyers in these cases should have done differently. In their place, I likely would have followed the same cautious route. Nonetheless, it is important to explore the unintended consequences of even the most successful advocacy. Truly eradicating the differential treatment of LGB families, and respecting individual choice in those we love, will require challenging mainstream norms themselves rather than simply imitating existing models.

I. historic plaintiffs

The couple who established the constitutional right to marry did so almost by chance. Mildred and Richard Loving were rural, high school educated, and knew no lawyers. After years of forced exile from their beloved home in Virginia, where their interracial marriage was a crime, they finally sought assistance.17 Yet these happenstance plaintiffs were a cause lawyer’s dream. Start with their name: the Lovings. Add to this their obvious affection for each other, their three adorable children, and their down-home self-sufficiency—Richard, a bricklayer and mechanic, built their house, and Mildred sewed the family’s clothes.18 As such, the average American could relate to them.

But the Lovings’ appeal was not only based on their personal qualities. The pair also obscured the racial biases at issue. Mildred was very light-skinned, with features and a hairstyle that were not obviously “black.” Moreover, sexual intimacy between white men and black women had long been overlooked, even condoned, in the South, in contrast to the opposite pairing—still a social taboo for some.19 The Lovings were also not involved in or associated with the broader civil rights movement.20 Their lawyers were able to portray them, honestly, as “very simple people” who did not want to upset the standard order, but just live together as a family in their quiet rural community.21 Indeed, they declined to attend the Supreme Court arguments on their case, and rarely granted interviews before or after, preferring to “lead quiet and simple lives away from the camera’s view.”22

Litigators since then have sought to find, and more often package, plaintiffs in the Loving mold. Results have been mixed.23 Among the most successful is Edith Windsor, the plaintiff in United States v. Windsor,24 the case striking down Section Three of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA).25 Dubbed “the perfect wife,” “Edie” was just that—beautiful, smart, elegant, monogamous, and a devoted caregiver to her disabled partner.26 The fact that she is white, well-educated, and wealthy no doubt also helped Supreme Court Justices relate to her. Most importantly, her lawyers portrayed her and Thea Spyer’s relationship as romantic and loving, but a decidedly G-rated version of lesbianism. A condition of Windsor’s representation was that she not speak publicly about sex.27

Lawyers have not always been so lucky, or so careful. Shortly after the Loving decision, a pair of lawyers set out to find plaintiffs to challenge the Texas ban on abortions.28 They chose Norma McCorvey, who became “Jane Roe” in Roe v. Wade.29 They picked Norma primarily because she was pregnant and poor, and overlooked her troubled history of substance abuse, psychiatric problems, and multiple sexual partners of both genders.30 Anti-choice advocates used her messy life against her, claiming it added support to their views.31 McCorvey repeatedly complained about herattorneys, claiming they treated her “like an idiot” and deliberately did not help her secure an abortion because they needed her to be pregnant for the larger cause.32 Driven partly by bitterness, McCorvey eventually switched sides, becoming rabidly anti-abortion. The pro-life movement made much of her “conversion” to their cause, seeing it as a “PR plus” for them.33 One leader gleefully noted that “[t]he poster child has jumped off the poster,” while another opined that “[t]he heart of the person who most symbolized abortion in this country has been touched and captured.”34 Although her lawyers tried to minimize her involvement at every stage, particularly after her defection, Roe remains a cautionary tale about the importance of careful plaintiff selection and management.35

More recently, in Lawrence v. Texas,36 cause lawyers saddled with unsympathetic plaintiffs successfully made over their clients. Dale Carpenter has uncovered the “real story” behind Lawrence.37 The two men lauded in an opinion about “relationships” and “enduring personal bonds” were not a couple, and perhaps not even lovers at all. Instead, John Lawrence and Tyron Garner were two “uncultured” low-income gay men—Garner was virtually homeless and Lawrence had convictions for ‘murder by automobile’ and DWIs—embroiled in a drunken argument with another friend.38 The Texas sodomy law was very rarely enforced and convictions never appealed as punishment was a relatively low fine.39 Indeed, Lawrence and Garner were likely arrested because they were rude to the officers at the scene, and advocates only learned of the unusual case via a closeted gay court clerk who happened across the arrest report.40 Given the rarity of arrests, LGB activists seized the opportunity, warts and all.41 To maintain cover and reframe a “booze-soaked quarrel” as a “love story,” their lawyers silenced Lawrence and Garner.42 In stark contrast to the Obergefell plaintiffs, they never appeared publicly without “minders,” and they were largely ignored by activists after the decision.43Sufficient funds could not even be raised for Garner’s funeral when he died destitute in 2006.44 One journalist articulated the attorneys’ fears when he asked why they kept their plaintiffs from the press: “Do you have to be perfect to win in the Supreme Court? Y’all didn’t want [their] blemishes . . . out there?”45 By keeping the true story of Lawrence and Garner hidden, lawyers gave the Court a tabula rasa upon which to inscribe its vision of sex and relationships—monogamous, committed, and private.46

II. obergefell plaintiffs

The Obergefell lawyers described seeking “a broad mix” of plaintiffs.47 Yet the plaintiffs they chose were largely homogenous and non-representative of LGB families.48 I reviewed over one hundred pleadings and media items to uncover four traits the publicity surrounding the case, and the plaintiffs themselves, emphasized: mainstream demographics, asexuality, children and caregiving, and political outsider status.49

A. All-American

The plaintiffs reflect a traditional “Leave it to Beaver” American ideal.50 They are overwhelmingly white and middle or upper-middle class, with men outnumbering women. Only five of the thirty plaintiffs are not white, and only three of the sixteen couples are mixed-race.51 This picture is starkly different than the gay and lesbian population, and also reflects the lessons learned from prior plaintiffs. LGBT people are more likely to be low-income and non-white than the average American, with particularly high representation among blacks.52 They are also twice as likely to be in an interracial relationship.53 The two African-American plaintiffs in Obergefell have worried, with reason, that the lack of diversity prevents the black community from seeing marriage equality as “their issue.”54 Building on the overwhelming welcome Edie Windsor received, however, lawyers seem to have chosen a group most attractive to the mainstream—studies show that white men are the most likely plaintiffs to garner support—rather than reflecting reality or affirming diversity as a value in itself.55

Like Windsor, the plaintiffs all have eminently respectable jobs. They are teachers, nurses, ministers, even soldiers. Twice in the opinion Justice Kennedy applauds plaintiff Ijpe DeKoe, who fought in Afghanistan, for “serv[ing] this Nation.”56 This contrasts with some of the less popular plaintiffs: Garner, an itinerant dishwasher and housecleaner, and McCorvey, who was sporadically employed as a bartender and “carnie.”57 None of the plaintiffs appear to be transgender, HIV-positive, have a criminal history, or even have visible tattoos. Those who are disabled or ill had more sympathetic diagnoses such as cancer or Lou Gehrig’s disease.58 They are pictured in Scout uniforms and in front of Christmas trees; they talk about holding cookouts and bonfires.59 As one plaintiff described himself and his partner: “We do exactly the same things as everyone else does. We teach our kids to ride bikes, we mow the lawn, we do laundry, we argue about money.”60 In an interview, the son of another plaintiff stressed that “[w]e’re just as boring and crazy and loud as any other family” and claimed that “people do see that we’re normal.”61

B. Asexual

A significant part of normalizing LGB people is obscuring their sexuality.62 It is no coincidence that most of the plaintiffs are either parents or widowers, so the focus is not on the couple alone.63 As Mary Anne Case has pointed out, gay rights become more palatable when the vision of “the gay couple copulating” is farther away.64Not one of the many photographs and videos available online depict a plaintiff kissing his or her partner. Sex is never mentioned—perhaps a legacy of the successful packaging of Edie Windsor. The plaintiffs have mostly been together for a significant time, several for twenty or even forty years.65 Their relationships are described as “committed” (read: monogamous).66 If anyone were inclined to contemplate plaintiffs’ sexual relationships, they could rest assured that those relationships are “proper.”

Any details that do not focus on children or household chores are very tame. Isn’t it sweet that Tim Love and his partner Larry wear matching T-shirts proclaiming “Love Wins?”67 And that two of the couples share the same name? (Kelly and Brittani, meet Kelly and Brittni.)68 Only one couple highlights the story of their relationship. Kim Franklin and Tammy Boyd met in high school and re-met and fell in love years later. But rather than the mature sexual attraction they felt for each other as adults, they describe “girlhood crushes” and a “sunset beach wedding.”69 Perhaps even that amount of detail was palatable because of the long history of tolerating lesbian, particularly girly, sex over gay male sex.70 These plaintiffs again differ from less model predecessors such as McCorvey who had three children by three fathers. They are what Katherine Franke has described as “legitimate homosexual[s] . . . willing to keep quiet about the sex part of homosexual.”71 As such, they overcome stereotypes of LGB people as promiscuous, and further entrench the cabined paradigm of sexuality the Court set out in Lawrence.

C. Children

Children have been front and center in the marriage debates. The parties and amici on both sides have centered their arguments on what is best for children, as did Justice Kennedy’s earlier opinions on same sex marriage.72Two-thirds of the plaintiff couples have children, far higher than the less than eighteen percent of LGB couples generally.73 Most poignantly, many have adopted children who would otherwise be orphans.74 The children are photographed, interviewed, and figure prominently in many couples’ express motivations for joining the lawsuit.75 Michael DeLeon describes his participation as “protect[ing] our children[] and . . . set[ting] a positive example.”76 April DeBoer signed on because she was “angry about [her] children not being treated equally,”77 an impetus Justice Kennedy praised as the wish of “all mothers . . . to protect their children.”78

Most of the plaintiffs without children have cared for their ill partners or an elderly parent.79 Indeed, the video of Jim Obergefell marrying his partner John, who was immobilized by ALS, brought many (including some of my colleagues) to tears.80 Jim and John’s video hearkens back to Windsor’s tale of caring for her disabled partner (although she did not reveal the difficult logistics of their sex life until after the decision),81 and the quiet self-sufficiency of the Loving family. Despite McCorvey’s sad story, the fact that she abandoned her three children renders her decidedly less sympathetic.82 And although Justice Kennedy described Lawrence and Garner’s relationship in terms of their “concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life,”83 the opinion contains none of the details of a life together which pervade the Obergefell narratives—because they did not have a life together.

This emphasis on caregiving not only further desexualizes LGB relationships, but also entrenches the privatization of dependency, exempting the state from responsibility for supporting the disabled and children. The reward of caregiving has played a central role in the advancement of gay rights. The first high court to recognize a same-sex relationship, Braschi v. Stahl Associates, noted Miguel Braschi’s care of his partner who was dying of AIDS.84The first state court to strike down a same-sex marriage ban similarly noted this function.85 This background helps explain the very disproportionate number of parents and caregivers among the Obergefell plaintiffs.

D. “Accidental Activists”

The final ingredient in the perfect plaintiff is a disdain for politics. The Obergefell plaintiffs have been cast as “ordinary” folks who just happened to get involved, like the Lovings. The press described one couple as “never [seeking] to make headlines, much less history . . . . They were nurses, not lawyers or activists.”86 Obergefell himself disclaims any past political interest, repeating, “No one could ever accuse usof being activists . . . . We just lived our lives. We were just John and Jim.”87

They protest too much. In contrast to the Lovings, none of the current plaintiffs truly became involved in the litigation through chance. Nor were they hastily selected out of necessity, like Roe and Lawrence.88 Several had been involved in previous LGB advocacy;89all were attractive candidates for careful recruitment by cause lawyers.90 To maintain the apolitical narrative, most cause lawyers are silent about the process of plaintiff selection. Several Obergefell lawyers, however, publicly acknowledged that they “built the case” before “finding plaintiffs,” and chose plaintiffs who are professional, monogamous, and attractive.91

And since getting selected, they have constantly been in the public eye—holding press conferences,92 being feted at advocacy galas, writing a series for Time magazine,93 and doing interviews with Katie Couric.94 All of them, many with their children, were at the Supreme Court the day of argument. Neither Roe nor the Lovings attended the oral arguments held in their names; although Lawrence did, he was “unrecognizable to most of the audience.”95 None of these plaintiffs spoke to the media—the Lovings by their choice, McCorvey and Lawrence by the machinations of their lawyers. In contrast, it did not come as a surprise when Obergefell recently announced a book and movie deal about his life.96

III. the costs of conformity

The plaintiff rubric developed over the course of cause litigation—from the successes of Loving and Windsor to the mistakes of Roe and Lawrence—is also evident in Obergefell. This rubric simultaneously dispels stereotypes about LGB culture and packages it as acceptable. The plaintiffs are not anti-family, too sexual, or too radical. They are religious—Maurice Blanchard’s Christian faith “guided his activism.”97 They are not even overly urbane and liberal hipsters.98

Choosing plaintiffs who seem “just like us” is undoubtedly a winning strategy. Yet it also reifies traditional norms, excluding the vast number of people, gay or straight, who do not fit the heteronormative marital model. To name just a few, the childless, polyamorous, low-income, multiracial, divorced, and flamboyant. Their exclusion can, perversely, hinder the quest for equality for all types of couples and families. That framing also helps enshrine marriage as the pinnacle of all relationships. Numerous scholars have argued that the focus on marriage equality has increasedmarriage’spowerfulregulatorypull.99My argument here is consonant with that critique, but specifically addresses the type of marriage the movement has endorsed. Fronting these mainstream plaintiffs emphasizes a particular type of relationship and family—traditional and conformist. It implies that marriage is only for the worthy and that the worthy will choose marriage.

Decades ago, anthropologist Kath Weston and others celebrated the transformative potential of the “queer” family.100 Granted, their work came at a time when not even scholars recognized the similarities between LGB people and others. Nonetheless, their “utopian” vision centered on choice and self-determination, and people choosing kin, rather than prioritizing blood and formal legal ties. Queer communities also celebrated sex outside of marriage and challenged the gendered, hierarchical spousal relationship undergirding family law.101 The framing of Obergefell obscures these differences between the queer family and the traditional family. Rather than celebrate the former and resist the latter, the Obergefell framing models the queer family after the heterosexual nuclear family, thus impeding recognition of a diverse and complex array of relationships.

LGB people have always been under intense pressure to conform. Conformity, however, can easily elide into excluding those who do not comply. We have replaced overt discrimination with more nuanced forms, wholesale animus with discrimination against those who will not or cannot assimilate.102 As Yoshino summarizes, “[o]utsiders are included, but only if [they] behave like insiders.”103 This assimilationist model also ignores intragroup differences of gender, race and class.104 The praise for the exemplary plaintiffs that permeates Justice Kennedy’s opinion, and the marriage-equality debate more broadly, further marginalizes those who do not “act straight.”105 A documentary released shortly after the Obergefell decision, titled Do I Sound Gay?, demonstrates the ongoing stereotyping of certain speech and movement patterns, along with the self-loathing, internal community policing, and external bullying that still torment many people who are gay or who seem to be.106 By emphasizing their “normalcy,” the Obergefell plaintiffs reinforce both this pressure to assimilate and the inferior status of the LGB community. They also downplay the challenges they have faced in overcoming stereotypes that gay people are promiscuous, anti-family, anti-American. Even marriage equality does not signal the end of homophobia: LGB people in the majority states remain unprotected against discrimination.107 Obergefell was one giant leap for equality, but it did not get us all the way there.

Conclusion

Obergefell plaintiff Paul Campion describes himself and his partner as “upstanding, productive citizens.”108 The assertion is undoubtedly true. But these perfect plaintiffs, and the celebration they received in Justice Kennedy’s opinion and throughout the litigation, cannot help but suggest that marriage and civic belonging are not human rights. Instead, they must be earned, earned by acting straight. I applaud the skilled and dedicated advocacy that led to marriage equality. Nonetheless, as scholars and advocates turn to the work that lies ahead for overall LGB equality, a more varied and representative depiction of families in future litigation can open up possibilities for recognizing and protecting the myriad ways people come together, love, and care for each other.

Cynthia Godsoe is Assistant Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School. For their helpful comments and suggestions, I owe thanks to Bennett Capers, Courtney Joslin, Melissa Murray, Evgenia Peretz, and Liz Schneider. I am grateful to Kaitlyn Devenyns, Maria Raneri, and Jessica Schneider for excellent research assistance and graphics, as well as to Rebecca Wexler, Joseph Masterman, Hana Bajramovic, and Michael Clemente for their thoughtful editing.

Preferred Citation: Cynthia Godsoe, Perfect Plaintiffs, 125 Yale L.J. F. 136 (2015), http://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/perfect-plaintiffs.

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) (holding that state criminal abortion laws that except from criminality only a life-saving procedure on the mother’s behalf violate the Due Process Clause); Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) (holding that anti-miscegenation laws violate the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses); Brown v. Board of Educ. of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (holding that separate schools for black and white students violated the Equal Protection Clause).

For instance, the Associated Press ran a series profiling each of the plaintiffs, which was widely reproduced in the media. See, e.g., Claire Galofaro, Associated Press, After Four Decades in Secret, Fighting for the Next Generation, LGBTQ Nation (Apr. 25, 2015), http://www.lgbtqnation.com/2015/04/after-four-decades-in-secret-kentucky-couple-fights-for-the-next-generation/ [http://perma.cc/7GPD-WY8T].

Heidi Hall, Same-sex Couple Thrives in Conservative Suburb, Tennessean (Mar. 22, 2014), http://www.tennessean.com/story/news/politics/2014/03/21/sex-couple-thrives-conservative-nashville-burb/6717331/ [http://perma.cc/B378-YNAP] (describing the approach of Johno Espejo and Matthew Mansell); see also Adam Polaski, Meet the Plaintiffs Standing Up for Marriage at the Sixth Circuit Today, Freedom to Marry (Aug. 6, 2014), http://www.freedomtomarry.org/blog/entry/meet-the-plaintiffs-standing-up-for-marriage-at-the-6th-circuit-today [http://perma.cc/A2P3-4B73] (quoting plaintiff Michael DeLeon as attempting to “make it clear that our family is not different from other families” and “want[ing] to show that our marriage is not different from other marriages”).

Numerous commentators have remarked upon this characteristic of the Roberts Court. See, e.g., Emily Bazelon, Marriage of Convenience, N.Y. Times Mag. (Jan. 27, 2015) (describing Chief Justice Roberts as “highly attuned to the way the public perceives the court”); Linda Hirshman, John Roberts’ Legacy Problem, Politico (Mar. 3, 2015), http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/03/john-roberts-legacy-115740 [http://perma.cc/ZK24-BKEG] (noting that Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kennedy are “most often mentioned” as “the conservatives on the court who are said to care most about popular opinion and legacy”).

See United States v. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. 2675 (2013) (holding that the refusal of the federal government to recognize same-sex marriages diminishes the dignity of these marriages); Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) (holding that laws which criminalize private homosexual conduct intrude into and demean the lives of homosexual persons and are therefore a violation of the Due Process Clause); Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996) (holding that no justification exists for a law which denies a group of persons protection from injuries caused by discrimination).

Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584, 2593-95 (2015). The plaintiffs’ lawyers explicitly criticize the defendants’ reliance on “abstract disquisitions” and neglect of the plaintiffs “at the heart of these cases: real people—men, women, and children.” Reply Brief for Petitioners at 1, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584 (2015) (No. 14-556).

My focus here is on the selection of named plaintiffs in appellate litigation, both in class actions and other impact litigation. While any person with standing and a valid legal claim can be a plaintiff, those named on the pleadings, like the thirty Obergefell plaintiffs, are the human faces of the case and, I argue, are thus carefully selected for their ability to appeal to the public and courts alike.

This myth was perpetuated in early school desegregation cases. See, e.g., Derrick A. Bell, Jr., Serving Two Masters: Integration Ideals and Client Interests in School Desegregation Litigation, 85 Yale L.J. 470, 497-502 (1976). The NAACP maintained that it “never looks for plaintiffs,” id. at 498 n.89, but Bell convincingly demonstrates that the organization gave “specific directions . . . as to the types of prospective plaintiffs to be sought,” id. at 498, and that litigation was driven primarily by the lawyers’ agenda, not the needs of individual litigants. See also William B. Rubenstein, Divided We Litigate: Addressing Disputes Among Group Members and Lawyers in Civil Rights Campaigns, 106 Yale L.J. 1623, 1652-53, 1632 n.47 (1997) (arguing that cause lawyers in LGB cases choose plaintiffs who do not reflect the realities of the community, and more broadly arguing that these lawyers should have a responsibility to the non-client members of the community as their strategic choices can greatly impact them).

Amanda Terkel et al., Meet the Couples Fighting to Make Marriage Equality The Law of the Land, Huffington Post (June 17, 2015, 2:58 PM), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/17/supreme-court-marriage-_n_7604396.html [http://perma.cc/KSK3-YDVX] (discussing the care that the attorneys took to find fitting plaintiffs willing to participate in the case); see also Joan Biskupic, Two Moms, a Baby and a Legal First for U.S. Gay Marriage, Reuters (Apr. 9, 2014, 8:54 AM), http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/04/09/us-usa-courts-samesexmarriage-idUSBREA380B420140409 [http://perma.cc/57HT-8XKH].

Based on the critical novel and film, The Stepford Wives, the term now indicates “blind conformity” or describes “someone who lives in a robotic, conformist manner without giving offense to anyone.” Stepford Wives, World Heritage Encyclopedia, http://self.gutenberg.org/articles/the_stepford_wives [http://perma.cc/FZ36-FBQ7].

These graphics are intended as a “snapshot” of the differences between the Obergefell plaintiffs and the general LGBT population. They are not intended to represent statistically significant differences. The information about the plaintiffs was garnered from the pleadings, media accounts, and communications with their attorneys (on file with the author). The income information was estimated from averages of the plaintiffs’ professions, available at various websites including salary.com, aavmc.org, glassdoor.com, payscale.com and others. Where possible, salaries were adjusted for the plaintiffs’ particular employer. In order to gain as accurate an estimate as possible, we cross-referenced multiple websites and adjusted for geographic area and length of employment.

The comparative information about the general LGBT population was taken from numerous sources. See Gary J. Gates, Demographics of Married and Unmarried Same-Sex Couples: Analysis of the 2013 American Community Survey, The Williams Inst. (Mar. 2015) [hereinafter Gates, Demographics], http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Demographics-Same-Sex-Couples-ACS2013-March-2015.pdf [http://perma.cc/3CQN-E6SA] (detailing demographic information, including racial, of the LGBT population); Gary J. Gates, LGB Families and Relationships: Analyses of the 2013 National Health Interview Survey, The Williams Inst. (Oct. 2014) [hereinafter Gates, LGB Families], http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/lgb-families-nhis-sep-2014.pdf [http://perma.cc/W3LK-89H8] (outlining family structure and demographic information for the LGBT population); Gary J. Gates & Frank Newport, Special Report: 3.4% of U.S. Adults Identify as LGBT, Gallup (Oct. 18, 2012), http://www.gallup.com/poll/158066/special-report-adults-identify-lgbt.aspx [http://perma.cc/Y6QC-5VNE]; Abbie E. Goldberg et al., Research Report on LGB-Parent Families, The Williams Inst. (July 2014), http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/parenting/lgb-parent-families-jul-2014/ [http://perma.cc/3MNJ-4LPG] (addressing research on LGB parenting); The 2013 LGBT Report, Experian Mktg. Servs. (June 2013), http://www.experian.com/assets/simmons-research/white-papers/2013-lgbt-demographic-report.pdf [http://perma.cc/WH4T-UXEE] (detailing income and demographic information for the LGBT population based on extensive market research and analyses). These sources include transgender individuals, whereas none of the Obergefell plaintiffs are transgender—another way in which they are more mainstream than the larger LGBT population. Transgender people represent a relatively small portion of LGBT people overall, so this omission should not skew the other results too heavily.

The plaintiffs’ lawyers deployed an intensive media campaign to acquaint the public with the plaintiffs’ stories. See infra Part II. The attorneys, whether they are from private or advocacy organizations, also depict these families on their websites. Typical is one law firm website, describing the Ohio plaintiffs’ hopes and dreams rather than their constitutional claims. See Meet Our Obergefell and Henry Marriage Equality Clients, Gerhardstein & Branch Co. LPA, http://www.gbfirm.com/meet-our-obergefell-and-henry-marriage-equality-clients [http://perma.cc/89N3-38AQ] (“The couple’s three children and David hope that the Court rules that the State of Ohio must recognize loving families like theirs . . . . The Henry-Rogers couple believes that Ohio’s denial of the true nature of their family demeans and harms them and their son, and they hope the Supreme Court will put a stop to that harm by their son’s first birthday.”). Even the Supreme Court briefings and oral argument, while of course outlining legal claims, contain a great deal of detail about the plaintiffs and their families. See, e.g., Brief for Petitioners DeBoer et al. at 3-6, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584 (2015) (No. 14-571); Transcript of Oral Argument at 22-23, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584 (2015) (No. 14-556) (plaintiffs’ attorney describing one plaintiff couple’s adoption of two children and their subsequent child care arrangements).

Dahlia Lithwick, Extreme Makeover: The Story Behind the Story of Lawrence v. Texas, New Yorker, Mar. 12, 2012, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/03/12/extreme-makeover-dahlia-lithwick [http://perma.cc/G9XW-BUFM].

This strategy diverges sharply from the queer critique of the very “idea of normal behavior . . . be it hetero or homo” and its “embrace of perversity.” Joshua Gamson, Must Identity Movements Self-Destruct? A Queer Dilemma, 42 Soc. Probs. 390, 395 (1995) (emphasis omitted). Scholars have pointed out this conflict between queer politics and LGB rights-based politics. See, e.g., Janet E. Halley, Sexual Orientation and the Politics of Biology: A Critique of the Argument from Immutability, 46 Stan. L. Rev. 503, 505 (1994).

Id.; Loving Decision: 40 Years of Legal Interracial Unions, NPR (June 11, 2007, 5:18 PM) [hereinafter Loving Decision], http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=10889047 [http://perma.cc/6V8W-UTEG].

Loving Decision, supra note 18. The contrast between the Lovings and the couple at the center of another key case on interracial intimacy just three years earlier, McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964), is vast. See id. at 196 (holding that a law criminalizing interracial cohabitation was a violation of the Equal Protection Clause). Dewey McLaughlin, a black immigrant man, and Connie Hoffman, white working-class woman, cohabitated in an admittedly “sexual relationship” but did not attempt to marry. Ariela R. Dubler, From McLaughlin v. Florida to Lawrence v. Texas: Sexual Freedom and the Road to Marriage, 106 Colum. L. Rev. 1165, 1170-72 (2006). Both married before, and likely still married to others when they were living together, the couple worked as a “sometime hotel worker” and waitress respectively, and Connie was investigated for mistreating her child. Id. at 1170-71. The case has received far less attention than it is due from both scholars and the public, particularly when compared to Loving. Id. at 1178-79 (noting this and constituting an important exception). The plaintiffs’ lack of mainstream appeal arguably contributed to this obscuration.

Ariel Levy, The Perfect Wife: How Edith Windsor Fell in Love, Got Married, and Won a Landmark Case for Gay Marriage, New Yorker, Sept. 30, 2013, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/09/30/the-perfect-wife [http://perma.cc/KA2Z-Y2RA].

Id. (quoting Windsor’s lawyer that “All [she] needed was Antonin Scalia reading about Edith and Thea’s butch-femme escapades”). After the decision, The New Yorker ran what has been called its “dirtiest, sexiest profile ever,” revealing that Edith was very capable of talking in detail about her sex life when she was permitted. June Thomas, The Dirtiest, Sexiest Profile The New Yorker Has Ever Run, Slate: Outward (Sept. 23, 2013, 2:48 PM), http://www.slate.com/blogs/outward/2013/09/23/_edie_windsor_profile_in_the_new_yorker_the_dirtiest_in_the_magazine_s_history.html [http://perma.cc/82PU-H2H5].

Joshua Prager, The Accidental Activist, Vanity Fair, Feb. 2013, http://www.vanityfair.com/news/politics/2013/02/norma-mccorvey-roe-v-wade-abortion [http://perma.cc/4DZQ-853F] (reporting that impact litigator Linda Coffee “was on the lookout for a plaintiff”).

Douglas S. Wood, Who is ‘Jane Roe’?, CNN (June 18, 2003), http://www.cnn.com/2003/LAW/01/21/mccorvey.interview [http://perma.cc/3RPK-543S]; McCorvey, supra note 30, at 126-28; see also Billy Hallowell, Do You Know the Fascinating and Troubling Story About the Woman Behind the Roe v. Wade Case?, The Blaze (Jan. 22, 2013), http://www.theblaze.com/stories/2013/01/22/do-you-know-the-fascinating-and-troubling-story-about-the-woman-behind-the-roe-v-wade-case [http://perma.cc/TLG3-FLNG] (quoting McCorvey that cause lawyers “were looking for somebody, anybody, to use to further their own agenda” and that “I was their most willing dupe”).

Prager, supra note 28; Sam Howe Verhovek, New Twist for a Landmark Case: Roe v. Wade Becomes Roe v. Roe, N.Y. Times, Aug. 12, 1995, http://www.nytimes.com/1995/08/12/us/new-twist-for-a-landmark-case-roe-v-wade-becomes-roe-v-roe.html [http://perma.cc/7FC4-YUU6]. Although, of course, McCorvey was never really a poster child.

After McCorvey joined the anti-choice movement, her attorneys commented that “[a]ll Jane Roe ever did was sign a one-page legal affidavit,” Prager, supra note28, and that her views didn’t matter because it was a class-action suit, ‘Jane Roe’ Joins Anti-Abortion Group, N.Y. Times, Aug. 11, 1995, http://www.nytimes.com/1995/08/11/us/jane-roe-joins-anti-abortion-group.html [http://perma.cc/M2Z8-R3QK]. These comments seem to support McCorvey’s complaints about her treatment by her attorneys.

See Katherine Franke, Public Sex, Same-Sex Marriage, and the Afterlife of Homophobia, in Petite Mort: Recollections of a Queer Public 156, 157 (Carlos Motta & Joshua Lubin-Levy eds., 2011) (stating that Lawrence “was premised upon a story [Justice Kennedy] made up” about the two men’s relationship).

To find out as much as possible about these plaintiffs, I repeatedly searched online for any information about them I could find. This included newspaper and magazine articles from both progressive and conservative publications, TV, radio, and web coverage, and press releases or other information put forth by their lawyers. The coverage was surprisingly consistent; that is, the information put forth by the plaintiffs’ lawyers was the same as that appearing in media across the spectrum. I would argue that the consistency reflects the very careful selection and grooming of these plaintiffs.

Historian Stephanie Coontz has documented how the “powerful visions of traditional families” created by 1950’s television sitcoms like Leave it to Beaver continue to inform political dialogue about the family, although they never reflected the majority of families. Stephanie Coontz, The Way We Never Were 23-30 (1992).

Gates & Newport, supra note 12 (reporting the disproportionately higher representation of LGBT status among nonwhite and lower income populations and noting that this “run[s] counter to some media stereotypes that portray the LGBT community as predominantly white, highly educated, and very wealthy”). Women are more likely to identify as LGBT than men. Id. About one quarter of those in same-sex couples are racial minorities. See Gates, Demographics, supra note 12. It should be noted that this data includes transgender individuals, who do not figure in the analysis here. Nonetheless, transgender people represent a small portion of LGBT people.

Ashleigh Atwell, Ohio Couple Changes the Face of Marriage Equality Fight, Elixher (Oct. 13, 2014) http://elixher.com/ohio-couple-changes-the-face-of-marriage-equality-fight/ [http://perma.cc/CP4U-HAZV].

Jennifer Richeson & Alexa Van Brunt, Same-sex Marriage and the Case of Race, The Hill (Apr. 29, 2015, 1:30 PM) http://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/judicial/240417-same-sex-marriage-and-the-case-of-race [http://perma.cc/MAR8-9NFV]. This preference for male plaintiffs also applies to non-white communities. See Richard Wolf, Everyday Heroes Etched in Supreme Court History, USA Today (Sept. 19, 2013, 9:52 AM) http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/09/18/plaintiffs-etched-in-supreme-court-history/2834421/ [http://perma.cc/C7DF-8FHG] (remarking that Oliver Brown may have been chosen as the lead plaintiff in Brown v. Board of Education because he was the only male plaintiff).

Respectively, Jimmy Meade and John Arthur (Jim Obergefell’s partner). See Claire Galofaro, supra note 2; A Perfect Day One Year Ago: The Marriage That Could Topple Ohio’s Wedding Ban, LGBTQ Nation (July 11, 2014) [hereinafter A Perfect Day], http://www.lgbtqnation.com/2014/07/one-year-ago-a-perfect-day [http://perma.cc/553M-ZYDV].

See Bob Allen, Gay Baptist Minister Followed Long Path to Marriage Equality, Baptist News Global (June 30, 2015), https://baptistnews.com/ministry/people/item/30232-gay-baptist-minister-followed-long-path-to-marriage-equality [https://perma.cc/WS9E-PEP7] (describing how Maurice Blanchard and Dominique James met at a cookout); Bourke v. Beshear & Love v. Beshear—Plaintiff Profiles, ACLU, https://www.aclu.org/bourke-v-beshear-love-v-beshear-plaintiff-profiles [https://perma.cc/C7TL-B2YH] (depicting Bourke and DeLeon in Scout leader uniforms); Claire Galofaro, A Long Road from High School Crush to Fight for Gay Marriage, Associated Press (Apr. 16, 2015, 3:10 PM), http://bigstory.ap.org/article/27f45f1ac76f4ac587b07f2547a5e183/long-road-high-school-crush-fight-gay-marriage [http://perma.cc/D9GH-HMEH] (explaining that Kim Franklin and Tammy Boyd hold bonfires with family); Polaski, supra note 3 (depicting Bourke and his family standing in front of a Christmas tree with their children).

Lily Hiott-Millis, 6th Circuit Plaintiffs Stand Strong In Face of Loss in Court Today, Freedom to Marry (Nov. 6, 2014, 5:00 PM), http://www.freedomtomarry.org/blog/entry/6th-circuit-plaintiffs-stand-strong-in-face-of-loss-in-court-today [http://perma.cc/J3XW-4K5T].

Amanda Terkel & Christine Conetta, “Just As Boring and Crazy And Loud As Any Other Family,” Huffington Post (April 20, 2015, 8:59 AM), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/04/20/paul-campion-randy-johnson_n_7057500.html [http://perma.cc/XH5A-D2B3].

Katherine M. Franke, The Domesticated Liberty of Lawrence v. Texas, 104 Colum. L. Rev. 1399, 1408-09 (2004) (“Just as the Court’s earlier Bowers decision and the military’s ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy overdetermined gay men and lesbians in sexual terms, we now celebrate a victory [in Lawrence] that at its heart underdetermines, if not writes out entirely, their sexuality . . . . The price of the victory in Lawrence has been to trade sexuality for domesticity—a high price indeed, and a difficult spot from which to build a politics of sexuality.” (footnote omitted)).

All of the female plaintiffs are parents, and half of the male plaintiffs are parents. See Infographic, supra note 12. One male plaintiff is both a widower and a single parent, David Michener, and the lead plaintiff, Jim Obergefell, is a widower. See Mark Sherman et al., Same Sex Marriage Plaintiffs’ Stories of Love, Life, Detroit News (Apr. 23, 2015, 2:52 PM), http://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/politics/2015/04/22/sex-marriage-plaintiffs-stories-love-life/26222099 [http://perma.cc/59QH-5ZQW]; A Perfect Day, supra note 58.

Until “Love” Wins in Kentucky: Tim Love & Larry Ysunza, Freedom to Marry (2014), http://www.freedomtomarry.org/story/entry/until-love-wins [http://perma.cc/TGY4-5SB5].

Atwell, supra note 54; see also Associated Press, Two Kellys Raising Baby As Loving, If Not Legal, Parents, Daily Mail (Apr. 16, 2015, 12:10 PM), http://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/ap/article-3042273/Two-Kellys-raising-baby-loving-not-legal-parents.html [http://perma.cc/FV2H-PCMT].

A Love Story 2 Decades in the Making: Tammy Boyd & Kim Franklin, Freedom to Marry (2014), http://www.freedomtomarry.org/story/entry/a-love-story-2-decades-in-the-making [http://perma.cc/WY33-PRAF].

United States v. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. 2675, 2694 (2013) (stating that DOMA “humiliate[d] tens of thousands of children now being raised by same-sex couples.”). For examples from the briefs in the cases that were consolidated with Obergefell, and the amicus briefs, see Brief in Opposition, Tanco v. Haslam, No. 14-562 (Dec. 15, 2014), which opposes same-sex marriage; Brief of 76 Scholars of Marriage as Amici Curiae Supporting Review and Affirmance, DeBoer v. Snyder, No. 14-556 (Dec. 15, 2014), which opposes same-sex marriage; Brief of Petitioners DeBoer et al., DeBoer v. Snyder, No. 14-571 (Feb. 27, 2015), which supports same-sex marriage; and Brief of Donaldson Adoption Institute et al. as Amici Curiae Supporting Petitioners, Obergefell v. Hodges, No. 14-556 (Mar. 6, 2015), which supports same-sex marriage.

As noted earlier, all of the female plaintiffs are parents, and half of the male plaintiffs are. Of the nine male plaintiffs who are not parents, one is a widower (Jim Obergefell), two lived with and cared for an ailing parent (Timothy Love and Larry Ysuza), another two describe their desire to adopt a child in the future (Maurice Blanchard and Dominique James), and another (Luke Barlowe) helped care for his partner Jimmy Meade who has cancer. See Terkel, supra note 9; Allen, supra note 59.

McCorvey’s mother adopted and raised her first daughter, born when McCorvey was a teenager, and she gave her next two children up for adoption. Prager, supra note 30. McCorvey argues that her mother tricked her into gaining custody of her eldest child, but McCorvey, a drug-using teenager at the time, did not seem capable of caring for a child. Id.; see also McCorvey, supra note 30, at 66-67, 76, 79, 86, 129-31.

Brian Dickerson, Couple Forged Unlikely Path to High Court Center Stage, Detroit Free Press (Apr. 27, 2015), http://www.freep.com/story/opinion/columnists/brian-dickerson/2015/04/27/sex-plaintiffs-path/26482941 [http://perma.cc/42FR-KXPF].

For instance, Greg Bourke had long advocated against the ban on gay Boy Scout leaders. Articles Tagging Greg Bourke, GLAAD, https://www.glaad.org/tags/greg-bourke [http://perma.cc/U8DP-GSC5].

See, e.g., Biskupic, supra note 9 (describing the careful recruitment of plaintiffs Tanco and Jessup). A typical approach to finding plaintiffs is that taken by a Florida LGB rights group, which advertised “Wanted by Equality Florida: Same-sex Couple Willing to Sue State of Florida over Gay Marriage.” Press Release, Equality Florida, Wanted by Equality Florida (July 3, 2013), http://www.eqfl.org/node/2650 [http://perma.cc/W3DF-6FCZ]. About 1,200 people applied and only twelve were chosen “representing a carefully crafted cross-section of South Florida.” Arianna Prothero, How Florida’s Gay-marriage Advocates Plan To Win in the Court of Public Opinion, WLRN (Apr. 16, 2014), http://wlrn.org/post/how-floridas-gay-marriage-advocates-plan-win-court-public-opinion [http://perma.cc/5LGF-56Y2].

See Jessie Halladay, Couple Challenges Kentucky Law Against Gay Marriage, USA Today, July 26, 2013, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/07/26/same-sex-marriage-kentucky/2589379 [http://perma.cc/96MA-V73S] (describing Kentucky lawyers as “decid[ing] that someone should challenge’ the state ban after Windsor and then “looking for a couple to work with on a lawsuit”); See also Amanda Terkel et al., ‘They’re Just Good People. And That’s Kind of What It’s All About, Isn’t It?,’ Huffington Post (Apr. 20, 2015), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/04/20/greg-bourke-michael-deleon_n_7024888.html [http://perma.cc/9HGL-NV3N] (describing lawyers from the Fauver law office “looking for plaintiffs to challenge [Tennessee’s] marriage equality ban” and finding Bourke and DeLeon “a perfect fit”); Interview with Lawyer in Same-sex Marriage Case (WBIR television broadcast July 1, 2015), http://www.wbir.com/videos/news/2015/07/01/29553165 [http://perma.cc/5FYM-L6SY] (quoting attorney Regina Lambert).

See, e.g., Michigan’s April DeBoer and Jayne Rowse at the U.S. Supreme Court, Detroit Free Press (Apr. 28, 2015), http://www.freep.com/picture-gallery/news/2015/04/28/michigans-april-deboer-and-jayne-rowse-at-the-us-supreme-court/26508163 [http://perma.cc/PVM5-6328].

See Ijpe DeKoe, Gay-Marriage Plaintiff: Our Names Are Now Part of the History of Marriage Equality, Time, May 1, 2015, http://time.com/author/ijpe-dekoe [http://perma.cc/2DWJ-LDTM].

Sarah B. Boxer, Meet the Plaintiff at the Heart of a Supreme Court Case That Could Legalize Same-Sex Marriage Nationwide, Yahoo News (June 3, 2015), http://news.yahoo.com/jim-obergefell-gay-marriage-supreme-court-plaintiff-interview-with-katie-couric-225816654.html [http://perma.cc/RHL3-H8GP].

Ryan Reed, Supreme Court’s Same-Sex Marriage Ruling Becoming a Feature Film, Rolling Stone (July 8, 2015), http://www.rollingstone.com/culture/news/supreme-courts-same-sex-marriage-ruling-becoming-a-feature-film-20150708 [http://perma.cc/CEK7-9BTH].

Hall, supra note 3 (specifying that the Espejo-Mansells live in a “nondescript,” untrendy neighborhood); see also Nina Totenberg, Meet the ‘Accidental Activists’ of the Supreme Court’s Same-Sex Marriage Case, NPR (Apr. 20, 2015, 4:27 PM), http://www.npr.org/2015/04/20/401007033/meet-the-accidental-activists-of-the-supreme-courts-same-sex-marriage-case [http://perma.cc/H3WD-VRUC] (describing another plaintiff couple, Paul Campion and Randy Johnson as “preppy-looking white men”). A hipster, defined as “a person who is unusually aware of and interested in” trends, see Hipster, Merriam-Webster (2015), http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hipster [http://perma.cc/3B2C-TLMD], is widely used in a pejorative sense. For instance, Senator Orrin Hatch labelled President Obama a hipster, bemoaning that the President was “putting the preferred lifestyle policies of wealthy urbanites ahead of the needs of blue-collar and union workers and middle-class Americans.” Sara Dover, Sen. Orrin Hatch on Keystone Pipeline: Obama Traded in ‘Hard Hat’ for ‘Hipster Fedora,’ Int’l Bus. Times (Feb. 29, 2012, 5:29 PM), http://www.ibtimes.com/sen-orrin-hatch-keystone-pipeline-obama-traded-hard-hat-hipster-fedora-418396 [http://perma.cc/5R5B-GPT3].

See, e.g., Nancy D. Polikoff, Beyond (Straight and Gay) Marriage: Valuing All Families Under the Law (2008); Angela P. Harris, From Stonewall to the Suburbs? Toward a Political Economy of Sexuality, 14 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 1539, 1569 (2006) (noting the potential negative consequences of “the absorption of queering the family into same-sex marriage”).

Scholars have critiqued family law’s myopic focus on the husband-wife relationship. See, e.g., Martha Fineman, The Neutered Mother, The Sexual Family and Other Twentieth Century Tragedies (1995) (recommending that family law shift to prioritize caregiving—that is, parent-child—relationships over the sexual tie between men and women).

See Devon Carbado, Black Rights, Gay Rights, Civil Rights, in Feminist and Queer Legal Theory: Intimate Encounters, Uncomfortable Conversations (2009) (describing the advocacy strategy addressing “Don’t Ask don’t Tell” military policy as “present[ing] a ‘but for’ gay man—a man, who, but for his sexual orientation, was just like everybody else, that is, just like every other white heterosexual person”).

Numerous scholars have cautioned that the marriage equality movement hinders efforts to “‘queer’ the family by embracing a wider array of family forms.” Melissa Murray, What’s So New about the New Illegitimacy, 20 Am. U. J. Gender & Soc. Pol’y & L. 387, 431 (2011); see also Michael Warner, The Trouble with Normal (1999) (critiquing the assimilationist spirit of the marriage equality movement).

The filmmaker took on this subject after a relationship ended and, back on the dating scene, he believed that his “voice repel[led] other gay men.” John Hartl, ‘Do I Sound Gay?’: Exploring Internalized Homophobia, Seattle Times, July 23, 2015, http://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/movies/do-i-sound-gay-exploring-internalized-homophobia/ [http://perma.cc/HQ3V-BKXX].

See Emily Bazelon & Adam Liptak, What’s At Stake in the Supreme Court’s Gay-Marriage Case, N.Y. Times, Apr. 28, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/28/magazine/whats-at-stake-in-the-supreme-courts-gay-marriage-case.html [http://perma.cc/64YH-EHM6] (predicting that post-marriage equality decision, “we are likely to be living in a world in which gay couples around the nation can be married in the morning and, in much of the country, be fired that same afternoon—for being gay”).