Off-Contract Harms: The Real Effect of Liberal Rescission Rights on Contract Price

This Essay also shows that, even if we assume that Brooks and Stremitzer are correct in arguing that sellers will be induced to lower prices, the redistribution of contracting surplus from seller to buyer that Brooks and Stremitzer predict will not result; the seller can simply recapture surplus by requiring up-front payments from the buyer. Moreover, insofar as rescission rights are worth more to low-value consumers, they effectively allow the seller to offer the good in question more cheaply to these consumers, much as a coupon would. And, like a coupon, this allows the seller to price discriminate and therefore to shift to herself some consumer surplus. Again, this is the opposite result of what Brooks and Stremitzer predict in their article.

I. Rescission Rights and the Seller’s Incentive To Lower Prices

Before critiquing Brooks and Stremitzer’s argument, this Part briefly lays out its mechanics. To be maximally charitable to their argument, I take as given the simplified legal framework they adopt, which includes only the right to rescission and the right to expectation damages and does not consider other relevant aspects of American contract law like the degree of perfection required in the tender or the seller’s right to cure.

The right to rescission and restitution allows a consumer to cancel a contract following breach by a seller and to receive back the contract price. A consumer will opt for rescission and restitution only when the contract is a losing one—that is, where the price exceeds the value of performance to the consumer. Adding some friction to the picture, rescission only will be attractive where the costs of opting for rescission are less than the loss that otherwise would be incurred by affirming the contract. If a suit is priced at $500, for example, and the value to the consumer turns out to be only $450, he will return the suit so long as the cost of doing so (in terms of time, hassle, transportation, etc.) is less than $50. Return can be very costly to the seller because she may be able to resell the suit only at a large discount, if at all (assuming, as Brooks and Stremitzer do, that the seller and buyer will not bargain to a different price). “By lowering the price,” Brooks and Stremitzer argue, “the seller can reduce the likelihood that the buyer will want to rescind the contract.”

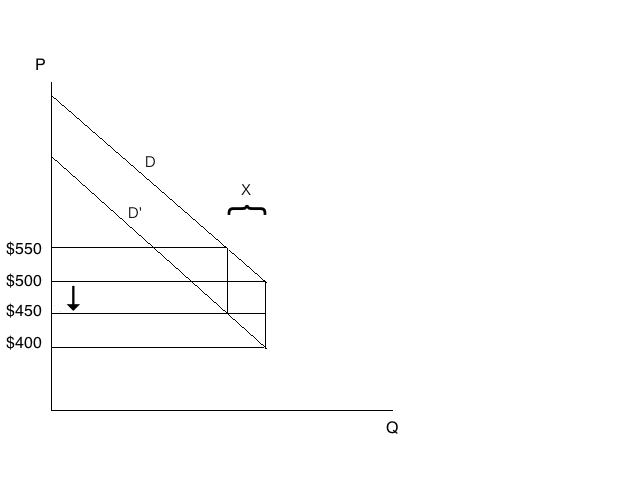

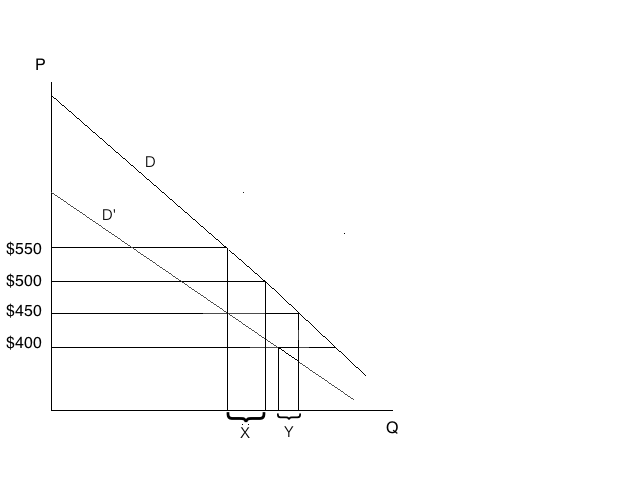

If we broaden the analysis to include multiple buyers, the effect they predict holds for some buyers. To illustrate, imagine that a suit is priced at $500 and turns out to be worth $100 less than the consumer anticipated because of a defect in quality. If the cost of return is $50, all those consumers who valued the suit between $500 and $550 ex ante and between $400 and $450 ex post will return the suit. These returns are costly to the seller. But if the seller lowers the price to $450, then the value anticipated and attained by all of these consumers increases by $50 and none of them opt to return. That these consumers no longer opt for rescission saves the seller the considerable cost of reselling the used goods at a reduced price. In Figure 1 below, the curve D represents the demand for the good (i.e., the value placed on it by consumers), and the curve D’ represents the demand for the good if consumers were aware of the defect before purchase (i.e., the value placed on it by consumers after the flaw has been discovered).

Figure 1.

Brooks & Stremitzer’s Effect

With the $50 drop in price, the consumer will now choose rescission only if his ex post valuation of the suit (D’) does not fall below $400. This is because a consumer receives $400 by returning the suit (the $450 contract price less the $50 cost of return). Previously, the consumer would have returned wherever D’ was below $450. By lowering the price, the seller thus prevents a number of consumers (X) from returning the suits. This, Brooks and Stremitzer argue, can induce the seller to lower her prices, which is socially desirable because it leads to redistribution in favor of the buyer and can curb the seller’s monopoly power where this power exists.

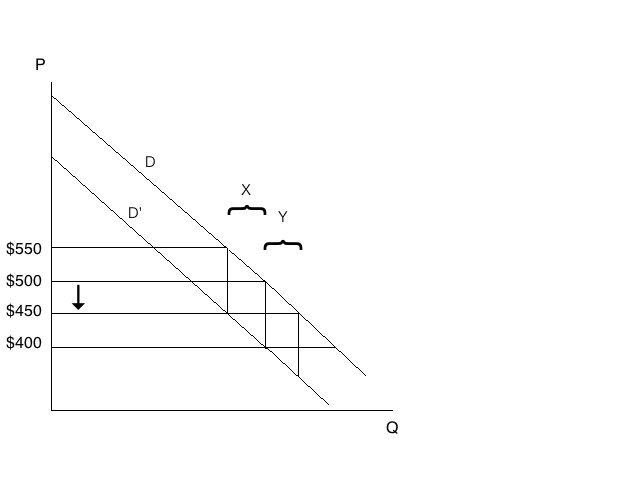

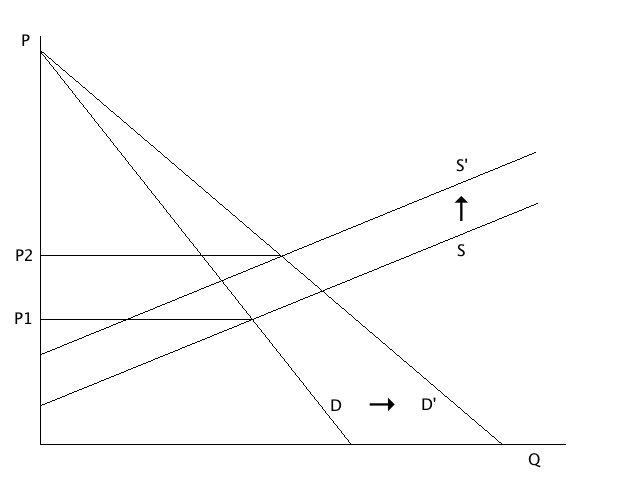

However, the overall effect on the number of returns is not so clear. What Brooks and Stremitzer critically omit in their analysis is the entry of new buyers after the price drop. Lowering the price to $450 means that the group of people who value the suit anywhere between $450 and $500 will now buy it. These consumers derive the least surplus from purchasing the suit and are most likely therefore to return it. In fact, given a $50 return cost, all of these new consumers will choose to return the suit upon finding that it is worth $100 less than they anticipated. So there is in effect a substitution, and not a diminishment, of consumers who rescind. And although the frequency with which buyers choose to rescind may be lowered because there are now a larger number of overall buyers, there is little reason to think that the seller would be concerned with frequency. Instead, she will calculate the aggregate costs of rescission, which remain constant. The substitution of rescinding customers can be seen in Figure 2 below:

Figure 2.

The Substitution Effect

Although the group of consumers who value the suit between $500 and $550 ex ante (X) will no longer return the suit after the seller lowers the price, the group of consumers who value the suit between $450 and $500 ex ante (Y) will now buy and return the suit. Recall that all those consumers whose ex post value (D’) is less than $400 will return the suit. At the original price of $500, those consumers represented by the region X are in an identical position with respect to the decision to seek restitution as are those consumers represented by the region Y at the new price of $450. Contrary to Brooks and Stremitzer’s claim, the seller will therefore not be induced to lower prices by reason of discouraging rescission.

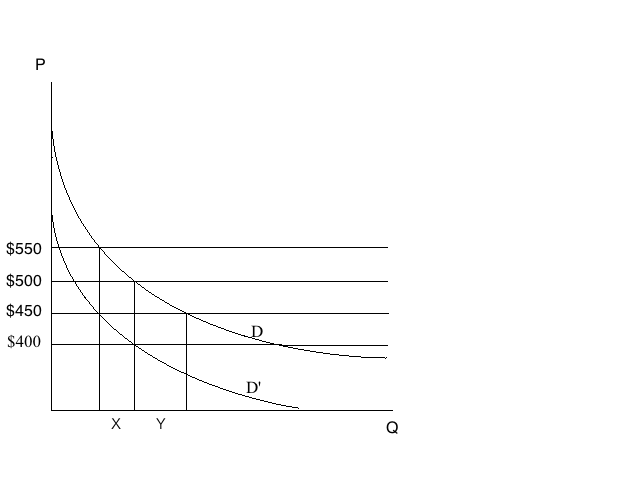

With a concave up demand curve, which is a more accurate representation of demand for a normal good like suits, Brooks and Stremitzer’s argument is even more problematic, as a drop in price results in an increase in the aggregate number of customers who return the suit. As can be seen from Figure 3 below, after a drop in price the number of customers no longer rescinding (X) is less than the number of new entrants who will choose to rescind (Y):

Figure 3.

Concave Up Demand Curve

Under these circumstances, liberal rescission rights would induce the seller to increase prices, all else being equal. This, of course, is the opposite of the incentive predicted by Brooks and Stremitzer.

One might argue in response that certain assumptions about the distribution of consumer valuations underlie both of the above examples and that under other circumstances a reduction in contract price would lower the number of rescinding consumers. But I do not mean to argue that this reduction can never occur. I mean to show only that, under some common distributional assumptions, the reduction does not occur, or that a drop in contract price may actually lead to an increase in the number of rescinding consumers. Therefore, without any evidence as to the likely distribution of consumer values and the corresponding incentives for sellers, we must remain agnostic as to the desirability of rescission rights by reason of their effect on price.

A further problem with Brooks and Stremitzer’s argument, as expanded to consider multiple buyers, is that reducing the contract price creates inframarginal effects that are costly for the seller. If the seller lowers the price of a suit from $500 to $450, she will lose $50 on every suit that she sells where the buyer does not seek rescission. Thus, even if we take as given Brooks and Stremitzer’s claim that reducing contract price will reduce the likelihood of rescission, it does not follow that the seller will have an incentive to lower price. Rather, the amount saved by reducing the frequency of rescission must outweigh these inframarginal costs in order for the seller to be induced to lower price.

II. Some Complications of the Effect on Price

For simplicity, the foregoing argument made two assumptions: (1) there is a defect in all of the suits sold such that the consumer’s ex ante anticipated valuation is always lower than his ex post actual valuation, and (2) the drop in value to the consumer that results from a defect is independent of the consumer’s ex ante valuation. Abandoning the first of these assumptions tends to show that a drop in price will increase the number of consumers opting for return, and abandoning the second tends to show the opposite.

In the real world, not all of the suits sold would have an identical defect. Instead, there would be some probability of a defect that lowers the value to the consumer and also some probability that the suit will be worth more than the consumer’s anticipated valuation (e.g., because the consumer comes to like the fit better, or because many wedding invitations were accepted after the purchase). The consumer’s ex post valuation would thus be some distribution of values with corresponding probabilities and the ex ante demand curve can be seen as a weighted mean. However, as discussed in Part I, this complication has no effect on the substitution of rescinding consumers, because the new consumers are in the same position as the old, whether their ex post values are probabilistic or not. We can illustrate this graphically:

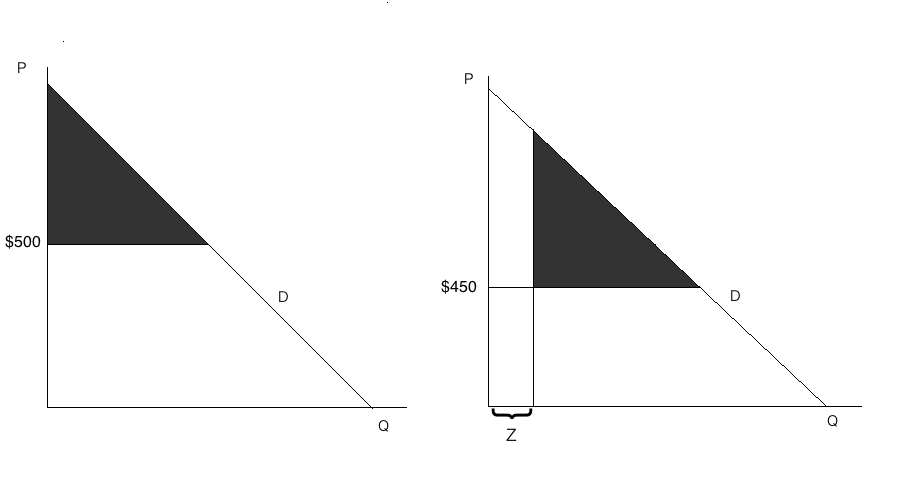

Figure 4.

The Probabilistic Model

Because the probability of return does not depend on the absolute price of the suit, but rather on the price relative to a consumer’s ex ante valuation, the consumers represented by the shaded triangles have identical probabilities of return. The only difference between the two situations, then, is the group of consumers shown after the price drop (Z). Assuming that those consumers have some nonzero probability of returning the good, there will be a greater number of returns after the price drop. All else being equal, this adds an incentive for sellers to raise, rather than to lower, their prices.

The argument in Part I also assumed that the difference between the ex ante and ex post value to the consumer was independent of the consumer’s ex ante valuation (in my example, it was always a flat $100). There might be reason to think, however, that this difference would be a percentage of (or some other function positively correlated with) the ex ante value rather than a flat number in certain cases. If, for instance, the consumer discovers a flaw in the suit, one might think that he is likely to discount the value of the suit by a greater amount the more he values the suit. Thus, the flaw might lower the value by 10 percent: $100 for the consumer who valued the suit at $1000 and $50 for the one who valued it at $500. After all, a flat $100 drop would not be possible for the consumer who values the suit at less than $100. If we assume that the drop between ex ante and ex post value to the consumer decreases as the consumer’s utility gained from the product decreases, the valuations for the product can be depicted as follows:

Figure 5.

Variable Drop In Value

Thus, the new buyers who enter because of the price drop have a smaller gap between their ex ante and ex post values than those who would have bought the suit prior to the price drop. In other words, these new buyers care less about the flaw in the good and are correspondingly less likely to opt for rescission and restitution. As depicted in the graph, the buyers who would have rescinded before the drop in price (X) are more numerous than those who will rescind after the price drop (Y). Therefore, a price drop marginally decreases the number of rescinding consumers under the assumptions here. This decrease, however, may be outweighed by the increase in the number of rescissions that occurs if we assume a concave up demand curve or probabilistic ex post values, as shown above, or by the inframarginal effects of a drop in price.

The more general lesson to be drawn here is that the effect of rescission rights on price becomes much richer and more complex once we broaden the analysis beyond Brooks and Stremitzer’s single buyer-seller relationship.

III.Rescission Rights and the Broader Market

We have seen that there is good reason to doubt that lowering prices will lead to a decrease in the number of rescinding consumers. If we set aside the effect of price on the probability of rescission and therefore also the incentives of a seller to raise or lower prices to affect this probability, there are independent reasons to think that a liberal provision of these rights will actually increase the cost of goods. Again, an analysis of these effects requires moving from the single buyer-seller context to a consideration of the effect of rescission rights on the market as a whole. Once this perspective is adopted, we see that rescission rights provide a valuable insurance function for consumers and increase the seller’s marginal costs, both of which will tend to raise the price for the good in question. This Part also demonstrates that the redistribution from seller to buyer posited by Brooks and Stremitzer—insofar as it actually occurs—will be skewed in favor of those consumers who derive the least surplus from purchase, which effectively allows the seller to price discriminate.

The right to receive back the price paid for an item effectively caps the potential loss on the purchase at the transaction costs of the return. Wherever the loss to the consumer is greater than the cost of return, he will simply return the good and incur this cost. To take the example above, the consumer who values the suit at exactly $500 would have lost $100 on the contract but for the rescission right. With the rescission right, the consumer returns the good and incurs only the $50 cost of return. This cap on the downside can be seen as a kind of insurance and is, of course, worth something to consumers. Just as consumers are willing to pay a higher price for goods that are more easily returnable, they will be willing to pay a higher price for goods where rescission rights are more liberal. So liberal rescission rights push the demand curve outward.

This increase, however, is not uniform for all consumers. Rescission rights that give the consumer back the contract price are worth more to those consumers who value the product least because it is these consumers who are most likely to make use of the rights. If, for instance, the value of a suit to a consumer is $1000 and its price is only $500, it is much less likely that a defect in quality will lead this consumer to opt for rescission than it would be for the consumer who values the suit at only $600. It may be useful, therefore, to think of the right to rescission as an option that is much further out of the money (and therefore less valuable) to the high-value consumer than it is to the low-value one. The redistribution effects that Brooks and Stremitzer posit would therefore not be simply from seller to buyer but also would favor low-value rather than high-value consumers. High-value users would effectively subsidize the provision of these rights to low-value consumers.

Moreover, because rescission rights are worth more to low-value consumers, rescission rights effectively allow the seller to offer the good in question more cheaply to these consumers. This price discrimination allows the seller to shift to herself some consumer surplus. Again, this is the opposite result of the redistribution in favor of the buyer that Brooks and Stremitzer predict. Rescission rights therefore function much as a coupon does, providing a discount to low-value consumers and allowing sellers thereby to discriminate.

On the supply side, the seller’s marginal costs increase with the increasing liberality of rescission rights and the corresponding increase in the number of returns. Liberal rescission rights also can be expected to lead to more aggressive use and experimentation on the part of consumers, who are emboldened by the insurance that these rights provide. The seller will anticipate these increased costs and gross up the price charged. The effect of liberal rescission rights on both demand and supply thus can be depicted as follows:

Figure 6.

Value and Cost of Rescission Rights

The price charged under a regime of liberal rescission rights (P2) is thus higher than that charged under a regime of more constrained rescission rights (P1). These broader effects further demonstrate that Brooks and Stremitzer’s conclusion regarding lower prices under a regime of liberal rescission may be unfounded.

IV. The Redistribution Effect

Even if we assume that Brooks and Stremitzer are correct in arguing that liberal rescission rights will induce sellers to lower their prices, it is not the case that this leads to a “redistribution effect,” shifting surplus from the seller to the buyer.

Brooks and Stremitzer argue that the seller cannot take back the surplus that shifts to the buyer as a result of the drop in price. Price is the usual tool for adjusting the distribution of surplus among parties, and in this case the seller is not free to raise the contract price because raising the price increases the probability of rescission (again, taking Brooks and Stremitzer’s claims about the seller’s incentive to lower price as given). But what Brooks and Stremitzer overlook is that the seller could simply charge a nonrefundable deposit to “recapture” the surplus that shifts to the buyer as a result of a drop in price. The inability to directly adjust the distribution of contracting surplus through the contract price thus does not limit in any way the seller with market power from charging the buyer for a more expansive right of rescission.

Brooks and Stremitzer’s neglect of this possibility is especially striking in light of the fact that they encounter the same issue when explaining how price can be used as a lever to adjust quality investment incentives under their rescission scheme: “When price acts as a lever to adjust incentives, however, it is not available as a tool to distribute the surplus among the parties. To achieve the distribution of surplus that reflects the parties’ respective bargaining powers, the parties therefore have to rely on up-front payments.” In precisely the same way, the seller could use up-front payments to make the buyer pay for the expansion of his rescission rights and to recapture the surplus that otherwise would shift to the buyer because of the drop in the contract price. The result is no redistribution effect even if we take as given the seller’s incentive to lower prices.

V. Conclusion

Once we broaden the analysis beyond a single buyer-seller relationship, the effect of liberal rescission rights on price becomes ambiguous. At the very least, Brooks and Stremitzer’s claim that a reduction in price will contribute to “considerably reduc[ing] the frequency with which the buyer chooses rescission” must be qualified. Although they are careful to note only that a seller may be induced to lower her price under a regime of liberal rescission rights, it equally is worth noting that a seller may be induced to do just the opposite. As this Essay has argued, under some very basic distributional assumptions, lower prices would lead to an equal or greater number of consumers who choose to rescind, thus implying an incentive to raise, and not to lower, prices. Moreover, even if we assume that Brooks and Stremitzer are correct in arguing that sellers will be induced to lower prices, no redistribution effect would result because the seller could recapture surplus by requiring up-front payments from the buyer.

Certainly, the observation that under some circumstances rescission can induce a seller to lower her price is remarkable and valuable, but until the likelihood of these circumstances is established, we should remain agnostic on the question of whether liberal rescission rights are desirable for this reason. Brooks and Stremitzer, however, go beyond this point to argue for a policy change favoring liberal rescission rights. Before this move can be made, much more has to be shown in terms of both the likelihood that prices will be lowered and the corresponding likelihood of distributive effects and effects on a seller’s monopoly power. Brooks and Stremitzer have thus failed to establish one of the two principal reasons that they offer in support of liberal rescission rights.

Michael Aikins is an Articles Editor of The Yale Law Journal and a member of the Yale Law School Class of 2012. The author would like to thank George Priest for his oversight of this project; Richard Brooks, Yair Listokin, Alan Schwartz, Brad Tennis, and Jason Wu for their helpful comments; and Ramya Kasturi and the editors of The Yale Law Journal Online.

Preferred Citation: Michael Aikins, Off-Contract Harms: The Real Effect of Liberal Rescission Rights on Contract Price, 121 Yale L.J. Online 69 (2011), http://yalelawjournal.org/forum/off-contract-harms-the-real-effect-of-liberal-rescission-rights-on-contract-price.