A Rosetta Stone for Causation

abstract. The law of mental causation—or motives—is a mess. It is as if writers in the field are using different languages to describe a multiplicity of causal concepts. The plethora of causal terms and lack of definitional clarity make it difficult to understand the relationship among causal concepts within a single area of law, let alone across substantive areas of law. To reach a clear and consistent understanding of this mess, it would be useful to have a Rosetta Stone—a translation key describing causal concepts and the relationships among those concepts in a precise and universal way. Andrew Verstein’s article, The Jurisprudence of Mixed Motives, comes close to reaching this ideal. However, his model suffers from two critical flaws: failing to justify a key analytical move and using terminology that is more confusing than it is universal. In this Response, I suggest remedies to those problems as well as a way to transform Verstein’s model into a Rosetta Stone for mental causation.

Introduction

To say that the law of mental causation is a complicated mess would be a gross understatement. The law of mental causation, also known as motive,1 has long been in need of a Rosetta Stone—a clear, precise, and universally applicable taxonomy of causal standards.

Many fields of law require inquiry into whether a particular mental state has caused a contested decision.2 For example, in employment law, courts must often examine whether an employer’s consideration of an employee’s race caused the employer’s decision to fire the employee.3

The complication begins with the fact that causation, whether in the physical or mental world, is not singular. There are several different types of causal relationships that any given law may require.4 In our firing example, for instance, the law might require proof that the employer would not have made the decision to fire the employee absent consideration of race (a type of causation called necessity, or but-for causation). Alternatively, the law might require only that race played some role in the decision to fire, irrespective of whether race was necessary to that decision (a type of causation that is sometimes called Motivating Factor causation).5 Or the law might require some other type of causal relationship or combination of causal relationships.6

The problem is that, in many areas of the law, it is not clear what type of causal relationship is required. Some laws invoke causation without even attempting to specify what type of causation they require.7 Others refer to causal standards that are undefined or ill-defined.8 And, to complicate matters further, legislators, courts, and commentators often use a wide variety of terms to refer to causal standards, making it difficult to identify the causal standards they are discussing, let alone to understand the relationship between the standards they reference. For example, in one famous case, the Supreme Court used over twenty different labels to describe the causation requirement in a landmark civil rights law.9

As an optimist, I have long believed that it should be possible to (1) identify the universe of potentially applicable causal standards; (2) clearly define each of those standards (and their relationship to one another); and (3) attach a universally applicable and accepted label to each causal standard. In other words, I believed that we might be able to create a Rosetta Stone to clear up the confusion that reigns in the Babel of mental causation. With such a tool, we could easily describe and identify the causal standards used in a particular field of law. We could engage in cross-substantive discussions of causation, so that judges and scholars in one field might learn from those in other fields. And we could engage in meaningful debates about the normative merits of any particular causal requirement. To mix my metaphors, such a Rosetta Stone would be a holy grail for the field of mental causation.

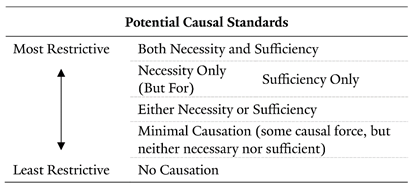

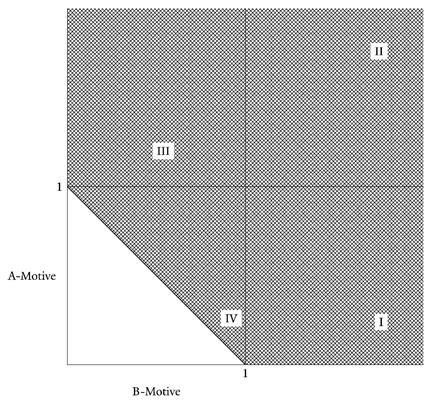

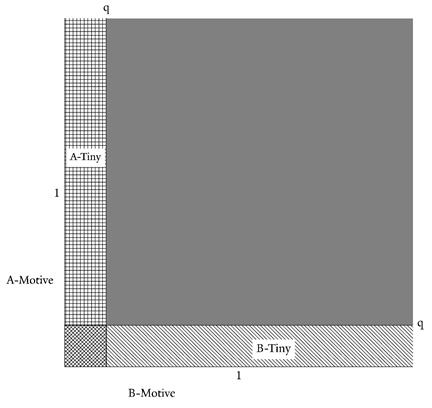

Several years ago, I started such a project.10 In the field of employment discrimination law, I identified a universe of six potentially applicable causal standards, precisely defined those standards and their relation to each other, and labeled them using (for the most part) terms that had been used to describe causal relationships for millennia. I even included a nifty graphic designed to show the standards and their relationship to each other, reproduced below as Figure 1.11

figure 1

potential causal standards from katz (2006)

I used this tool to make sense of current employment discrimination law standards and to address their normative implications.

I hoped that this tool might make it possible to explore causal standards in other fields of law, such as constitutional law. But as a law school dean, I never found time to take that next step in cross-substantive study. So I was thrilled to read Verstein’s exciting article, The Jurisprudence of Mixed Motives, which undertook just such a project using his own nifty graphic.

I know that scholars are supposed to be defensive of their own work, but when I read Verstein’s piece, my first reaction was that he had considered much that I had not—bringing us much closer to the Rosetta Stone that I had been seeking. He also made tremendous progress on the cross-substantive project. My next reaction was that his article contains some flaws that prevent his framework from achieving Rosetta Stone status. My final reaction was that those flaws can be remedied. And if we do so, we will indeed have found our Rosetta Stone. That is my project in this Response.

Part I explains the exciting potential of Verstein’s article. Parts II and III explore two problems with the piece that significantly undercut its potential utility. Part II describes the article’s lack of a compelling justification for one of the most important and exciting parts of its analysis. Part III notes the use of confusing terminology, which is particularly problematic in a project designed to promote clarity. For each of those problems, I suggest solutions. My hope is that those solutions will complement and complete Verstein’s project, making it more useful and accessible as a clear, precise, and universally applicable taxonomy of causal standards—a Rosetta Stone for mental causation.

I. big steps forward

The goal of scholarly debate is to advance the state of knowledge and understanding in its field. Verstein’s article does exactly that. In my case, his article made me also realize that my own framework of causal standards lacked some important parts that significantly impaired its utility.

First, my framework lacked a quantitative, or scalar, component.12 The standards in my framework—which are based on the logical causal relationships of “Necessity” and “Sufficiency”—are purely qualitative, or binary. Take Sufficiency, for example. We can say that a mental state (consideration of race) was sufficient to trigger a particular decision (firing). But Sufficiency is binary. Something is either sufficient or insufficient. It makes no sense to say that a factor is more sufficient or less sufficient. The same is true of Necessity. A mental state (consideration of race) may be necessary to the occurrence of a decision (firing), such that the event would not have occurred absent the existence of that mental state. But this, too, is binary. It makes no sense to say that a factor was more necessary or less necessary.

However, a quantitative conception of mental causation—admitting of degrees—would permit an expansion of the universe of potential causal standards. Instead of being limited to saying that a factor was necessary or sufficient, we might be able to say that a factor was a “big influence” or a “small influence,” or that one factor was “more influential” than another. This, in turn, might permit the articulation and use of quantitative standards for causation that might supplement or even replace qualitative standards. For example, we might meaningfully require that a motive exert a certain level of causal influence (e.g., “more than de minimis”), or that the motive exert more of a causal influence than other motives.13

Additionally, a quantitative conception of causal influence might clarify the relationship between causal standards in a way that is not possible using purely qualitative concepts. In my model, using only quantitative conceptions, I was able to depict the relationship between causal standards on a single axis: some standards are more restrictive (and thus, more defendant-friendly) than others.14 Yet, this understanding is limited. First, it cannot help us compare Necessity to Sufficiency. Looking at restrictiveness can help us see that a compound standard requiring both of those standards (Necessity-and-Sufficiency) is more restrictive than a non-compound standard requiring only one of them. But it does not permit us to say whether a Necessity standard is more or less restrictive than a Sufficiency standard.15 The other problem with this single axis approach is that there may be other ways besides restrictiveness to conceptualize the relationship between Necessity and Sufficiency.

Verstein posits and develops exactly such a quantitative approach.16 His model permits us to examine the causal influence of a particular motive, both absolutely (a motive might be considered weak or strong), and comparatively (one motive might be considered stronger than another). He then uses this quantitative conception of motives to depict the interaction of motives graphically, with axes that represent the relative causal force of each motive, as well as the level of causal force that is independently sufficient to trigger the event in question.17

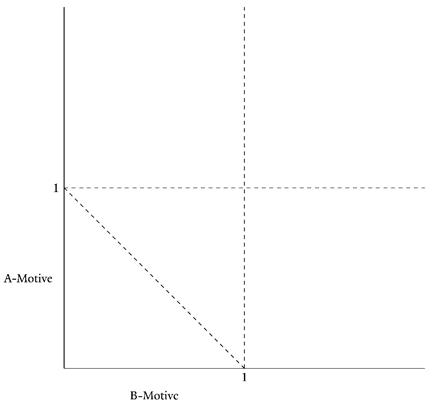

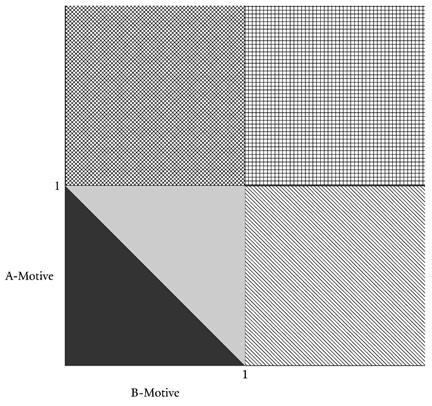

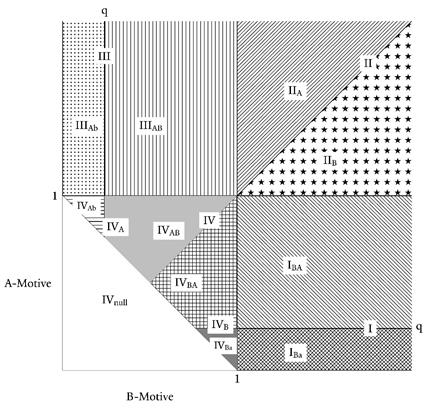

figure 2

verstein’s graphic model18

Verstein’s graph depicts a simplified world with two motives, one (B-Motive) which is proscribed by the law (such as the race in firing employees), and the other (A-Motive) which is permitted (such as tardiness in firing employees). His graph permits us to visualize motives as having causal force and interacting with each other. As we move outward along each axis, we can see the causal force of each motive increase. If the causal force of either motive, or of the combined motives, crosses the threshold value of 1 (Verstein’s designator for Sufficiency), that combined force will trigger the decision in question. This occurs anywhere above and to the right of the diagonal dashed line connecting the 1s on both axes. But if the force of A-Motive alone crosses that threshold, it means that A-Motive alone is sufficient, which in turn precludes B-Motive from being necessary (or a “but for” cause). This occurs anywhere above the dashed line extending horizontally from the 1 on the A-axis. The graph also allows us to see quantitative concepts, such as whether there is “a lot” of B-Motive or only “a little,” and whether there is more B-Motive than A-Motive.

This incredibly useful visual aid permits a precise understanding, and thus, precise description, of the universe of potential causal concepts, both qualitative and quantitative. In other words, it appears to be an excellent foundation for the type of Rosetta Stone that I hoped someone might be able to create. And armed with this tool, Verstein starts the extremely valuable project of cataloging the causal standards used across a wide range of substantive areas of law.

However, despite this significant accomplishment, there are two flaws in the article which, if not addressed, may prevent Verstein’s excellent framework from becoming the Rosetta Stone of mental causation. First, Verstein fails to provide an adequate justification for the quantification of mental causation that lies at the core of his model. Second, instead of using standard causal terminology in his model and his taxonomy, Verstein creates a new taxonomy, which may cause more confusion and decrease the utility of the model he has developed. The good news is that these flaws can be fixed. I propose solutions in the following Parts.

II. justifying the quantification of motives

As noted above, the key analytical move underlying Verstein’s project is the idea that motives can be quantified. Without quantification, we are left with only the traditional qualitative measures of causation. And without the quantification of motives, it would not be possible to construct the graphs on which Verstein relies to develop his taxonomy.19

Yet, despite the importance of quantification to his project, Verstein does little to justify his quantification of motives. His primary justification is based on an intuition about a qualitative—not quantitative—conception of motive. He notes:

We observe that some people subject to A-Motives act on them, and some find them insufficiently motivating and do not act. Likewise, the same individual may act on A-Motives one day and not another. It would seem that some motivations are sufficient to prompt action, and some are so weak as to be ignored, particularly when there are costs to action.20

His point is that we can intuitively observe that some motives are sufficient to trigger action, while others are not. Yet, as noted above, sufficiency is a qualitative concept, not a quantitative one. The intuition that a motive may be sufficient or insufficient does not support the idea that we can or should think of motives as quantifiable.

Note that we can probably make similar intuitive observations that would more directly support the idea that motives might be quantitative: we might sense that a particular motivation feels strong or weak. Similarly, when making decisions based upon multiple considerations or motives, we might sense that some of our motivations seem stronger, while others seem weaker. And we can have these quantitative intuitions irrespective of their qualitative result—that is, irrespective of whether a motivation (or combination of motivations) is sufficient to trigger a particular decision.

However, even this intuitive observation, while more tailored to the argument that motives can be quantified, does not fully support the quantitative model. This is because the question we must answer is not a psychological one about how motive actually works inside the human mind. While that is an interesting question, and while the intuitive observation above may give us some comfort that the answer to that psychological question is consistent with a quantitative model, the key question is actually a legal one: Does the law conceptualize motivation as quantitative, or at least permit such a conceptualization?21 I will argue that it does.

The starting point for this analysis is to embrace the notion that the law sees motives as causal. In fact, many (if not most) of the laws that require inquiries into motives actually speak in terms of causation. For example, Title VII, the landmark civil rights law, does not speak of motive; rather, it prohibits adverse employment actions (such as firing) where those actions occur “because of” certain protected characteristics (such as race or sex).22 That is, the law uses the language of causation to describe a mental state. That relevant mental state is generally described as “motive.”23 So the inquiry, under these laws, is whether the motive in question caused the decision in question. In other words, the law treats motive as a form of mental causation.24

We can measure causation in three different ways. First, we can use a measure of existence: either a casual factor was present, or it was not. This measure is workable where the law looks only at a single causal factor (which was either present or not). But this measure does not work where the law considers the interplay between multiple causal factors (mixed motives), as it often does.25 In such cases, we can measure causation in a second way: qualitatively. For example, we might ask whether a particular factor was sufficient to trigger a particular outcome, or whether the factor was necessary to the outcome. Note that these measures do not expressly attempt to ascribe values to causal forces. A force may be sufficient to trigger an event irrespective of whether it is a large force (a heavy brick on a camel’s back) or a small force (a straw on a camel’s back). Similarly, a force may be necessary for an event to occur irrespective of whether it is a large or small force, since whether a factor is necessary to cause an event depends on the existence and causal force of other factors. Hence, we can refer to these measures as qualitative. Yet there is also a third way we might measure causation: quantitatively. That is, we may think of factors as carrying certain causal weights, such that those with more causal weight are more likely to trigger an event.

In the physical world, we can easily see how the law (as well as the laws of physics) embrace quantitative conceptions of causation. Take, for example, the ubiquitous discussions in tort law about the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back.26 These discussions envision that physical forces have measurable weights (such as the weights of cars on a bridge or straws on a camel), which exert causal force toward an event (such as the collapse of the bridge or the camel). The weights, or other physical measures, are understood as quantities, which can be compared to each other and to the quantities required to trigger an outcome.

The law seems to extend this physical view of causation into the world of mental causation. In many places, the law expressly makes this analogy. For example, in antidiscrimination cases in employment law and constitutional law, which involve mental causation (motive), the courts have routinely looked to concepts of physical causation from tort law to inform their analysis.27

But even where the law does not make the analogy expressly, I would argue that it often does so implicitly, and that Verstein’s quantitative move is therefore justified. This is because the law of mental causation wholeheartedly adopts qualitative concepts of causation (necessity and sufficiency).28 And those qualitative concepts, in turn, are built upon quantitative conceptions of causation. Consider the causal concept of sufficiency. The concept asks whether a factor will trigger an event. Thus, the concept seems to posit that (1) the factor carries some quantum of causal force and (2) the event has a trigger point that depends on the total quantum of causal force from that factor along with other factors. (The axes in Verstein’s graphs illustrate this quite well.) In turn, the concept of necessity depends on the concept of sufficiency. The thing that prevents one factor from being necessary is the existence of another factor that is sufficient. Thus, both of the core qualitative concepts in causation—necessity and sufficiency—which are expressly invoked in mental causation cases, contemplate a quantitative view of motives as causal forces.29

For these reasons, applying a quantitative conception of motives, as Verstein does, seems justified. The Rosetta Stone’s foundation seems solid.

III. a universal taxonomy

To be truly useful as a Rosetta Stone, a framework of potential causal standards must not only be comprehensive, precise, and based on a solid conceptual foundation; it must also employ a universally accepted (or acceptable) taxonomy. The very need for a Rosetta Stone comes from the fact that different people use different terms to refer to the same concept. If I refer to a concept as blue-causation, Verstein refers to the concept as green-causation, and a judge trying to apply the concept refers to it as yellow-causation, we run the very serious risk of failing to communicate—or, at the very least, failing to communicate effectively. In fact, it is exactly this type of confusion that seems to have motivated Verstein to develop his framework.30

This Part argues that Verstein uses terminology that risks moving us further from a uniform lexicon for causal concepts. This is not simply a debate about preferences for particular terms over others. The primary point of both Verstein’s article and my 2006 article is to catalog and label the universe of potential causal concepts in a clear and authoritative way, in order to facilitate meaningful identification and discussion of those concepts.31 If the labels we introduce depart from those that are commonly used and understood, this goal is less likely to be realized. To avoid this problem, I will offer a translation of the causal concepts that Verstein identifies into traditional causal language. I will then provide a comprehensive “key” to show how those causal concepts can be used alone or in combination to form legal tests or standards.

A. Adding Confusion to an Already-Confused Field

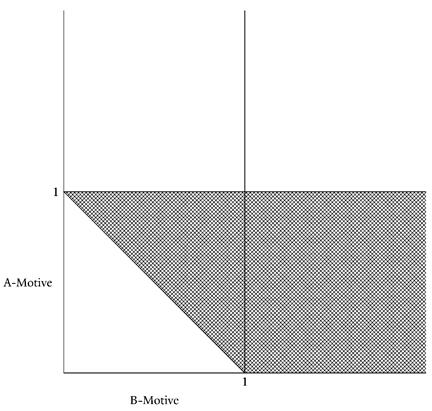

Rather than rely or build on existing terms for causal concepts, Verstein adds yet more terms to a world that already suffers from too many. For example, consider his basic graph32:

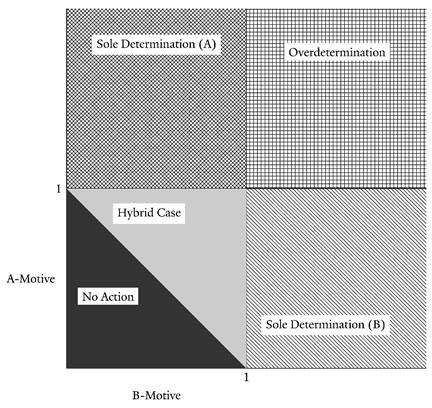

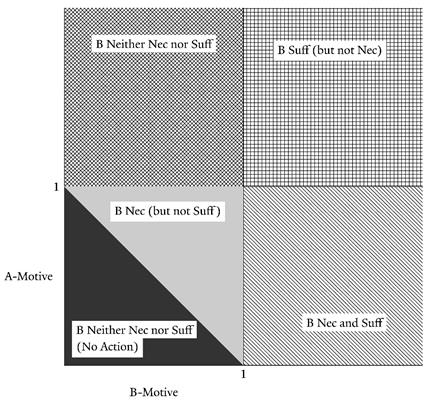

figure 3

verstein’s new terminology

In this one graph, Verstein introduces five new causal terms: Sole Determination (A), Sole Determination (B), Overdetermination, Hybrid Case, and No Action.33

Adding to the confusion, he also seems to use these terms in ways that are at odds with some existing usages. For example, he uses the term “overdetermination” to describe cases in which there are two independently sufficient causes (the upper right-hand quadrant). But other authors have used the term “over-determined” to refer to cases in which the factor in question (B-Motive) is not necessary (or a but-for cause), which happens any time that A-Motive is independently sufficient (represented by both of the upper quadrants).34 Similarly, Verstein uses the term “Sole Determination” to describe the upper left-hand quadrant (in which B is neither necessary nor sufficient) and the lower right-hand quadrant (in which B is both necessary and sufficient). However, most writers who use the term “sole” to describe causation are referring to cases where B-Motive is present and no other relevant factors, such as A-Motive, are present (that is, A=0). These labels introduced by Verstein are at odds with existing usages, and thus particularly confusing.35

The situation becomes even more confusing when Verstein moves from defining causal concepts to defining tests that appear to be based on some of those causal concepts, like his description of what he calls the “Sole Motive” test36:

figure 4

verstein’s “sole motive” test

The shaded area in this test has no apparent connection to the “Sole Determination (A)” concept discussed above, and overlaps only slightly with the “Sole Determination (B)” concept, though this test bears a much closer resemblance to the existing usage of the phrase “sole causation.”37

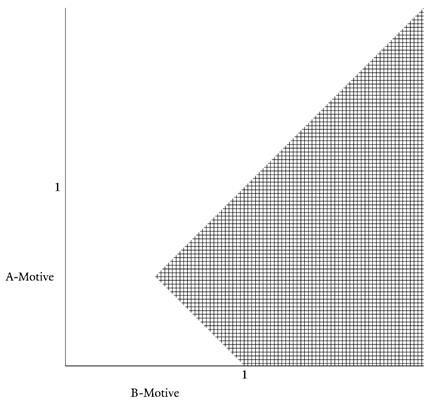

Or consider the test Verstein labels “Any Motive”38:

figure 5

verstein’s “any motive” test

The label “Any Motive” makes it sound as if the test is satisfied so long as any motive (A-Motive or B-Motive) is present. But the point of the test is to describe cases in which B-Motive is present (B>0) and the event in question has occurred (A+B>=1). The existence of A-Motive is largely irrelevant in this test, creating yet another confusing label.

With all of these new, and often confusing, labels, Verstein’s model risks not living up to its potential. To serve as a Rosetta Stone, the model must use terminology that is universally applicable and universally (or at least widely) accepted. Verstein’s frequent use of new and confusing terminology makes it unlikely that the model can accomplish this. Fortunately, this problem can be remedied. That is my project in the next Section.

B. Translating Verstein into Traditional Causal Concepts

To start with, it will be helpful to distinguish causal concepts (or causal attributes) from causal tests. Causal attributes can be thought of as building blocks for causal tests. For example, we can think of necessity and sufficiency as causal attributes. They can be used either alone or in conjunction with other causal attributes to form causal tests. For example, the law might require (1) Necessity, (2) Sufficiency, (3) Necessity but not Sufficiency, (4) Sufficiency but not Necessity, (5) both Necessity and Sufficiency, or (6) either Necessity or Sufficiency. These six causal tests are built using the two causal attributes—or building blocks—of necessity and sufficiency.

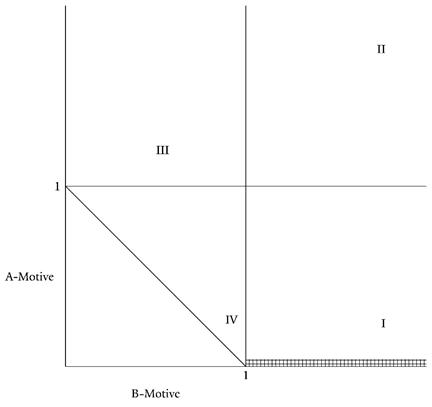

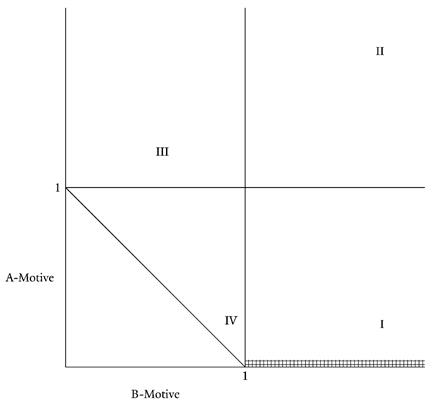

Verstein’s illustrates these two traditional causal attributes (necessity and sufficiency) graphically. Yet, he applies nontraditional—and confusing—labels to these attributes. This problem can be remedied by translating his graph into traditional causal language. We can start using his basic graph (minus the labels)39:

figure 6

verstein’s basic graph

This graph essentially depicts the two traditional qualitative causal attributes related to B-Motive: necessity and sufficiency.40 We can see this by changing Verstein’s labels as follows:

figure 7

verstein’s basic graph—translated

Note that the point is not merely to relabel the graph. Rather, it is to note that the graph essentially shows combinations of the two traditional, qualitative causal attributes: necessity and sufficiency. As noted above, those concepts have been in use for millennia and are widely used and accepted. No new terms are required to describe them.41

C. Nontraditional Causal Concepts

By focusing on the relationship between Verstein’s work and these traditional causal concepts of necessity and sufficiency, we can also see where Verstein has identified less traditional causal concepts (which are not likely susceptible to traditional causal labels). Two such concepts are apparent in his basic graph. First, consider the black triangle in the lower left-hand corner. That triangle can be described as depicting an area in which B-Motive is neither necessary nor sufficient. But we can say the same about the upper left-hand quadrangle. The distinction between these two regions, which is highlighted by the label Verstein uses for the black triangle, is that, in the black triangle, the decision or action in question will not occur. The two motives, individually or in combination, are insufficient to trigger the action (A+B<1).

Verstein tends to discount the usefulness of this region. On one hand, this may be the right approach if we adopt a “no harm, no foul” norm.42 On the other hand, irrespective of harm, the defendant in this zone has engaged in proscribed behavior, having applied some quantum of B-Motive in the decision-making process, even if he or she failed to reach an adverse decision. But my point here is not to debate whether any particular law does or should impose liability in this region. Rather, the point is that if our goal is a complete catalog of potential causal concepts, we should include this one.

That leaves the question of how to label the concept reflected in this part of Verstein’s graph (the lower, left-hand, black triangle). Unlike the concepts of necessity and sufficiency, no well-established label has routinely been applied to the concept reflected in this zone. Given that the point of the zone is to denote an area in which there is no action, Verstein’s label of “No Action” to describe the zone seems appropriate. This still leaves the question of how to refer to the causal attribute in question. Because the zone (and Verstein’s label) reflects the absence of an attribute (action), we might refer to the causal attribute as “Action.”43

Second, on Verstein’s basic graph, we can identify a fourth causal attribute (in addition to necessity, sufficiency, and action). Consider the entire area of Verstein’s graph above the B-axis; that is, the area in which there exists some A-Motive (A>0). In this zone, the illicit motive (B-Motive) cannot be an exclusive causal force in the decision; another non-proscribed motive (A-Motive) has exerted at least some quantum of causal force in the decision. As Verstein notes in his discussion of his “Sole Motive” test, there may be situations where we might want to let a defendant use the existence of A-Motive (A>0) as a defense to the existence of B-Motive—irrespective of the causal force exerted by that B-Motive.44

As with action, this concept does not have a commonly-used label. The causal concept here focuses on exclusivity—whether, as between A-Motive and B-Motive, B-Motive is the exclusive motive for the decision. Hence, I will refer to this causal concept or attribute as “exclusivity.”45

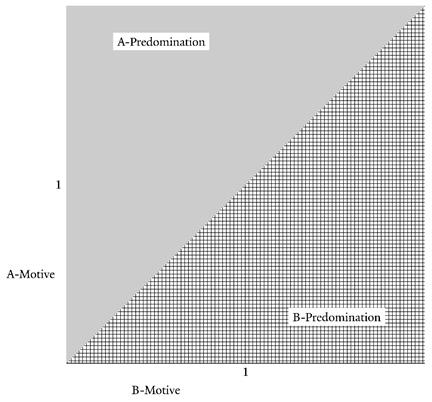

Finally, when we move beyond the basic graph to the graphs that Verstein uses to illustrate his two new quantitative causal concepts, we can see that new terminology is also likely to be required. (By definition, these quantitative concepts are not susceptible to labeling using qualitative terms.) These graphs suggest two new causal concepts. The first new concept is apparent from his graph titled “Relative Motives”:46

figure 8

verstein’s relative motives graph

Here, we see the idea that we might require B-Motive to exert more causal force than A-Motive. Verstein uses the label “B-Predomination” to describe this concept. However, since the model is inherently focused on B-Motive, we can simply refer to this concept as “Predomination.”

The second new quantitative concept is apparent from Verstein’s graph entitled “Tiny Motives.”47

figure 9

verstein’s tiny motives graph

In this graph, we can see the distinction between “big” and “little” causes. More specifically, Verstein posits a dichotomy between causes that may carry insufficient weight to be considered material. He refers to those causes as “tiny.” But the causal concept is really about whether a cause can be considered non-tiny (B>q). So a better way to describe this concept is the one that Verstein uses later in his piece: “Material.”48

D. Putting It All Together

The prior Sections identified what appears to be the universe of six potentially relevant causal concepts, or building blocks. Where possible, I have labeled these concepts using traditional, widely used labels. We can list that universe of causal concepts—and describe them—as follows:

- Necessity (A<1 and A+B>=1)

- Sufficiency (B>=1)

- Predominance (B>A)

- Materiality (B>q, where q is the point of non-tininess)

- Exclusivity (A=0)

- Action (A+B>=1)

Now, for any area on Verstein’s graph, we can indicate whether the B-Motive possesses that particular causal attribute—or any combination of causal attributes that might be required by a particular test.

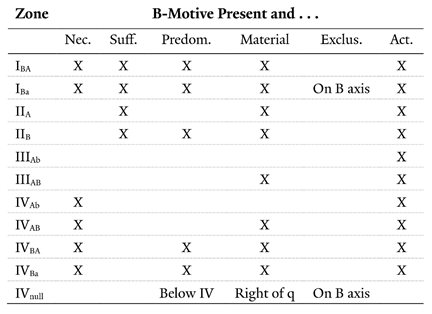

To illustrate, I will use Verstein’s Complete Map, which designates regions using numeric labels49:

figure 10

the complete map of potential causal concepts

We can then evaluate that graph against the universe of causal attributes as follows:

figure 11

the key to causal concepts

This, I would submit, is our Rosetta Stone. It combines Verstein’s Map with a Key to explain the entire universe of potential causal concepts.50 The Map and Key clearly define each of those concepts. And the Key attaches a universally applicable (and what I hope is a universally, or at least widely acceptable) label to each concept.51

When presented with a causal phenomenon in the world (or, at least in the hypothetical world with only two motives), we should be able to locate it on the Complete Map, and then use the Key to determine the causal attributes of that phenomenon. Conversely, when presented with a description of a causal test in the law, we should be able to interrogate which of the six causal attributes the test seems to require. Then, based on the constellation of causal attributes required, we can depict the test on the graph—such that we can determine whether an observed fact pattern satisfies the test.

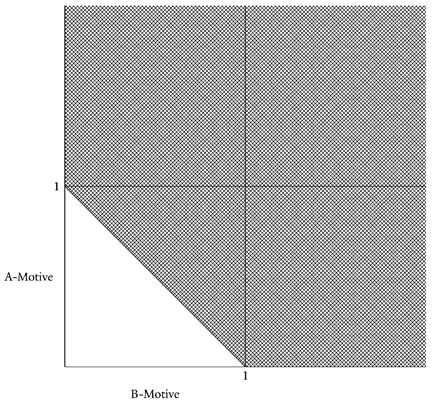

For example, suppose that we conclude that, upon finding the existence of B-Motive (B>0), a particular law requires only Action (A+B>=1); it does not require any of the other five causal attributes. We could present that test on a graph as follows:

figure 12

the “motivating factor” test

This graph is similar to the graph that Verstein presents to depict his “Any Motive” test.52As Verstein notes, the graph is likely the best understanding of the “Motivating Factor” test used in the Civil Rights Act of 1991 (at least with the slight modification to exclude the A-axis, since there must be at least some B-Motive).53

Or suppose that, upon finding the existence of B-Motive (B>0), the law requires both (1) an Action (A+B>=1), and (2) Necessity (A<1). We could present that test graphically as follows:

figure 13

the necessity (or “but for”) test

This is the “but for” test, which Verstein depicts and which he notes is used in numerous areas of the law.54

Conversely, we can use the Map and Key to deconstruct graphically-defined tests into their component causal attributes. For example, consider the Primary Motive test posited by Verstein55:

figure 14

the “primary motive” test

This test appears to require (1) Predominance (B>A), and (2) Action (A+B>=1).

Or consider the Sole Motive test posited by Verstein56:

figure 15

the “sole motive” test

This test appears to require (1) Exclusivity (A=0), and (2) Action (A+B>=1).57

* * *

My point here is not to decode the various tests that Verstein has identified, though it is certainly possible to do that using the Map and Key. Rather, it is to illustrate that, using the Map and Key, we can (1) identify the universe of potentially applicable causal attributes, (2) clearly define each of those attributes and their relationship to one another, and (3) attach a universally applicable (and hopefully universally acceptable) label to each causal attribute. This, in turn, should allow us to describe precisely any causal test that is based upon those attributes—which should include all possible causal tests. In other words, with the additions proposed here, I believe that Verstein has found the Rosetta Stone.

Martin Katz is the Chief Innovation Officer at the University of Denver, and Professor of Law and former Dean at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law; J.D., Yale Law School ’91.

Preferred Citation: Martin Katz, A Rosetta Stone for Causation, 127 Yale L.J. F. 877 (2018), http://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/a-rosetta-stone-for-causation.

This piece is a Response to Andrew Verstein’s article, The Jurisprudence of Mixed Motives, 127 Yale L.J. 1106 (2018). Verstein focuses on motives, as opposed to causation, to avoid taking a position on the question of whether motives should be considered causal in human decision making. See id. at 1124. As will be discussed below, whatever one might believe about the role of motives in decision making as a matter of psychology or philosophy, the law treats motives as causal. See infra note 27 and accompanying text. Accordingly, I treat the question of motives in the law as a question of causation.

See, e.g., 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a) (2012) (requiring that the adverse employment action, such as firing, must be “because of” the specified motivation, such as consideration of race, but not specifying any particular type of causal relationship). This particular statute was amended in 1991 to attempt to clarify this question. See Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-166, 105 Stat. 1071 (1991). Numerous other anti-discrimination laws use similar language. See, e.g., Age Discrimination in Employment Act (“ADEA”), 29 U.S.C. §§ 623-633(b) (2012); Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”), 42 U.S.C §§ 12101-12117 (2012).

I use the term “quantitative” to mean the ability to evaluate the presence of “more” or “less” of something. I do not claim (and Verstein does not appear to claim) to have discovered or conceptualized a unit of measure for motive or mental causation (other than “Sufficiency,” which is the quantum of causal force that will trigger the decision or event in question). Accordingly, I do not use the term “quantitative” to mean being susceptible to precise, numerical measurement.

Verstein also introduces the very helpful concept of “independent sufficiency.” In my framework, I identified two types of sufficiency: strong and weak. Katz, supra note 4, at 497 n.25. Factors that were strongly sufficient would trigger the event in question irrespective of any other factors that might be present. It is actually hard to imagine such a factor. As explained by Mark Kelman, “[G]iven that the injury cannot have occurred unless the plaintiff (P), at a minimum, existed, that is P is invariably a necessary condition for the damage to occur, we can never causally attribute any injury solely to a second party, a defendant (D).” Mark Kelman, The Necessary Myth of Objective Causation Judgments in Liberal Political Theory, 63 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 579, 579 (1987). Hence, in my analysis, I relied on the concept of weak sufficiency: a factor that, when combined with all other factors then-present, will trigger the event in question. Verstein’s concept of independent sufficiency is similar. But instead of looking at all other factors that are present at the time of the event in question, he looks only at the other factor that is under consideration, and then posits the absence of the other factor. Thus, looking at two forces, A and B, he would say that B is independently sufficient if, when added to all other factors then present other than A, B would trigger the event. Put differently, in a two-factor world (only A and B), B is independently sufficient if it would trigger the event in the complete absence of A. This is a highly useful concept, and when I refer to sufficiency here, that is the concept to which I refer.

Perhaps it is for this reason that Verstein eschews the question of whether his model is psychologically accurate. See id. (noting that his model is “not meant to literally describe human psychology”). Avoidance of this issue is probably wise because, irrespective of the accuracy of a view that ascribes quantifiable strengths to human motivations, as law professors, we likely have little to add to that particular debate. Like Verstein, I do not make any claims about the psychology of motive. Nor do I make any claims about whether, as a prescriptive matter, the law of motive should be consistent with the best psychological research on motive. Rather, my project here is a descriptive one focused on the law of motive.

See Sheila R. Foster, Causation in Antidiscrimination Law: Beyond Intent Versus Impact, 41 Hous. L. Rev. 1469, 1471 n.4 (“Notably, others have pointed out that the intent requirement in both constitutional and statutory law is better understood as a causation requirement.”). Verstein expressly avoids discussing causation. Verstein, supra note 1, at 1124 (“This Article avoids causal language whenever possible.”). He does so because he understands that some commentators have problematized the application of causal concepts to mental states. Id. at 1124 n.77 (noting H.L.A. Hart and Tony Honoré’s rejection of determinism in causation). However, irrespective of the psychology or philosophy of motives as causation, the law has unequivocally embraced the idea that motives can be understood and evaluated as being causal in human decision making. See D. Don Welch, Removing Discriminatory Barriers: Basing Disparate Treatment Analysis on Motive Rather than Intent, 60 S. Cal. L. Rev. 733, 739 (1987) (“Motive is a causal concept. It comes into play when a concern exists that decisions were made ‘because of’ or ‘on the grounds of’ certain factors.”). Moreover, Verstein’s whole framework is organized around a distinctly causal concept: sufficiency. The most important value on his graph—the one that distinguishes almost all of the causal concepts in his taxonomy—is the value of one, which he defines as representing the level at which a motive becomes independently sufficient to trigger the decision in question. See Verstein, supra note 1, at 1125-27.

The multiple factors can be physical factors, such as the famous two-fires case in tort law. See James A. Henderson, Jr. et al., The Torts Process 145-47 (5th ed. 1999). Or the multiple factors may be mental factors, as in the many areas ably catalogued by Verstein. See Verstein, supra note 1, app. B at 1170.

See, e.g., Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228, 241 (1989) (plurality opinion) (employing the “simple example” of “two physical forces” that are each quantitatively sufficient to cause a certain outcome to illustrate that the presence of two sufficient causes does not mean that neither “caused” the result); Mt. Healthy City Sch. Dist. v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977). Additionally, courts routinely use quantitative-like language to describe causal concepts. See, e.g., Price Waterhouse, 490 U.S. at 262 (O’Connor, J., concurring) (discussing a situation where an employer gives “substantial weight to an impermissible criterion”).

This argument says nothing about measurement or proof of quantitative motive. We do not have units by which to measure the causal force of motives, much less a good way to examine the inner workings of a person’s mind (or a group’s “mind”). For these reasons, asking parties to prove, and factfinders to evaluate, the mere existence of a particular motive can be problematic. Asking them to quantify that motive seems like an even more difficult task. However, as noted above, these tasks are inherent in the law’s command that we engage in the qualitative and quantitative evaluation of motives.

Note that all of the labels I will use for causal attributes will be B-centric. That is, when I refer to necessity, I mean to say that B-Motive is necessary. Or when I refer to sufficiency, I mean to say that B-Motive is sufficient. I use this convention because the whole point of the model is to describe the causal status of B-Motive—the motive that, when considered causal, is proscribed by the law.

I understand that Verstein had a reason for eschewing traditional causal taxonomy: he seeks to avoid taking a position in the debate about whether motives should be considered causal, and whether doing so leaves sufficient room for the concept of free will. See Verstein, supra note 1, at 1124. For that reason, he prefers his own labels over labels that embrace a causal view of motives. However, he cannot escape the fact that many (if not most) of the areas of law he references expressly invoke causal language—such as “because of”—in relation to motives. Moreover, the majority of Verstein’s framework is built around the causal concept of sufficiency. The only value specified in his graph is the number one, which he uses to designate the point at which a motive becomes sufficient to trigger the action in question. So, like it or not, he seems to be talking about motives as causal. He might as well embrace that and accept the benefit of using causal labels that are likely to be more universally understood (and used) than his own new, and somewhat idiosyncratic taxonomy.

Verstein does provide translations between his taxonomy and traditional causal language—though, for some reason, he refers to the latter as the language of tort law (which happens to use the language of traditional causation). See, e.g., Verstein, supra note 1, at 1128 n.88. I would suggest that putting quasi-translations in footnotes does not make it likely that readers will easily understand and use his new, idiosyncratic taxonomy. In any event, just in case, I will provide the translation in text, rather than in footnotes.

Verstein discounts the utility of casual tests based on this concept because he assumes that we would never want to punish people for motives that do not lead to action. Verstein, supra note 1, at 1129-30. Justice O’Connor articulated a similar idea, noting that we should not punish people for thought crime, and that Title VII was not a “thought control bill.” Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228, 262 (1989) (O’Connor, J., concurring). As a normative matter, that may be a correct statement. But it is hard to make—much less justify—this normative conclusion if we do not even consider it. Hence, I will include this causal concept in my catalog.

Verstein, supra note 1, at 1139-41. Note that we can identify a converse concept to sole causation. Just as we might ascribe significance to the presence of A-Motive (A>0), we might ascribe significance to the presence of B-Motive (B>0). This can be understood as a distinction between the vertical axis (where there is no B-Motive) and everything to the right of that axis (where there is some B-Motive). However, I do not include this in my catalog of causal concepts because, as a practical matter, the model effectively assumes B>0. Recall that the legal question that the model seeks to address is whether B-Motive can be considered causal. It is hard to see how we can discuss whether B-Motive is causal without assuming that B-Motive exists. Accordingly, I do not include this concept in the catalog.

Some courts and commentators have sometimes referred to a causal test they call a “Sole Cause” test. See Robert Belton, Causation in Employment Discrimination Law, 34 Wayne L. Rev. 1235, 1238 (1988) (“Congress and courts have uniformly rejected the ‘sole cause’ test.”); Verstein, supra note 1, at 1139. As I will discuss below, that test uses the attribute of exclusivity, along with the attribute of action. I prefer the label of exclusivity, as opposed to soleness, both because the focus of this attribute is on the absence of the other factor (A-Motive), and because soleness seems awkward as a descriptor for the attribute.

It is tempting to resist the notion of exclusive, or sole, causation, since it is hard to image a person who is ever animated by only one, single-minded motivation. See Dare v. Wal-Mart Stores, 267 F. Supp. 2d 987, 991 (D. Minn. 2003) (“In practice, few employment decisions are made solely on basis of one rationale to the exclusion of all others.”)110 Cong. Rec. 13,837 (1964) (statement of Sen. Case) (“If anyone ever had an action that was motivated by a single cause, he is a different kind of animal from any I know of.”). However, this concern misapprehends the model. B-Motive is not a sole cause in the sense of excluding all other causal influences. Rather, it is a sole cause in the sense that the other potentially relevant (and potentially exculpatory) cause—A-Motive—is not present.

As noted above, where possible, I used labels that have been widely used, which should advance the goals of universal applicability and wide acceptability. Where there were no widely used labels, I attempted to find labels that captured the essence of the concept in question, which I hope furthers these goals.