Fighting for the Common Good: How Low-Wage Workers’ Identities Are Shaping Labor Law

Social movements led by workers in low-wage industries, from fast food to car washes to nursing homes, have upended the public narrative of who poor workers are and what they deserve both at work and at home.1 By doing so, these movements have won victories that were once considered “unrealistic” and “doomed.”2 As a result of the Fight for $15’s campaign,3 for example, nearly seventeen million U.S. workers have earned wage increases, and 59% of those—ten million workers—will receive gradual raises to $15 an hour.4 In fact, between 2012 and 2016, workers earning less than $15 gained $61.5 billion in wage increases.5 However, the workers who lead and drive these movements are not simply agitating for a higher wage. As Jorel Ware, a McDonald’s worker from Chicago and member of the Fight for $15, states it:

What’s motivating me is there’s a lot of different issues going on in the United States with living wages, with Black Lives Matter issues, immigration reform, childcare. These issues are basically the same because everybody’s going through them, black and brown people are going through this. This is how it comes together and it gives me the drive and I’m finally willing to make a change.6

Jorel’s desire for broad-based change that cannot simply be bought with a higher wage is emblematic of the desires of large numbers of low wage workers, a disproportionate number of whom are women, Black, and Latino. Although public attention has focused on their success in lifting the minimum wage,7 workers are also demanding greater political and economic equality in the form of an agenda that addresses systemic racism, sexism, and other forms of structural discrimination.

Seen in this light, it is no surprise then that low wage workers are turning to labor unions. As Professor Benjamin Sachs has written, labor is “the legal regime that has most successfully facilitated lower-and middle-class political organizing.”8 Labor unions, in turn, are responding to low-wage worker organizing by acknowledging the intersectional identities of these workers. Out of this recognition of their members’ identities, we see emerging what commentators have coined as “common-good unionism”9—that is, a form of union organizing that addresses social conditions whether or not they are directly related to traditional terms and conditions of employment. Unions are thus increasingly pursuing innovative strategies spurred by the need to address the multifaceted and complex nature of inequality in the United States. The resurgence of tripartite, sectoral bargaining that Professor Kate Andrias extolls in The New Labor Law is but one salient example of this emerging trend.10 Like the fight for an eight-hour day and the weekend before it, common-good unionism is bringing about positive change not just for the benefit of union members but for all people who are similarly situated. We see common-good unionism as the better predictor of the future of labor law and its increasing intersection with other areas of law and organizing.

In this Essay, we therefore shift the focus from the legal strategies that low-wage workers and their advocates are currently using to the workers themselves.11 By taking a closer look at these workers’ identities and demands, we argue that the strategic innovation in low-wage worker campaigns is driven not merely by a need to overcome economic and legal barriers to organizing in the fissured economy, but also by the needs of marginalized workers, which require going beyond traditional labor law and sometimes beyond the law altogether. Part I provides a picture of the workers making less than $15 and presents the economic and social factors shaping their demands. Part II provides a broad overview of the kinds of legal and non-legal strategies that low-wage worker movements are using to raise the visibility of the most disenfranchised workers and address the discrimination and inequality they face both within and outside the workplace. Finally, in Part III, we provide a sketch of the “common-good unionism” we see being shaped by a deliberately intersectional analysis12 of the needs of workers and their communities.

I. low wage worker movements advocate for a workforce that is disproportionately composed of women and people of color

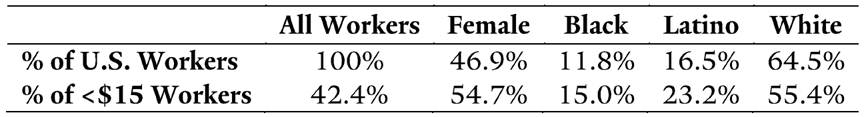

Workers in low-wage industries endure a host of challenges that create instability in their lives, including “on-call scheduling, missed breaks, generalized disrespect, and [ ] physical and emotional tolls.”13They are also among the most marginalized in our economy. While 42% of the U.S. workforce—more than fifty million workers—now earns less than $15 an hour,14 the lowest wages in our economy are earned in marked disproportion by women, Blacks, and Latinos.15

table1.16

|

In fact, close to half of all women workers, more than half of all Black workers, and just shy of sixty percent of all Latino workers earn less than a $15 hourly wage17—what researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology say is the baseline wage necessary in the vast majority of U.S. communities to “live locally given the local cost of living” while supporting one child.18

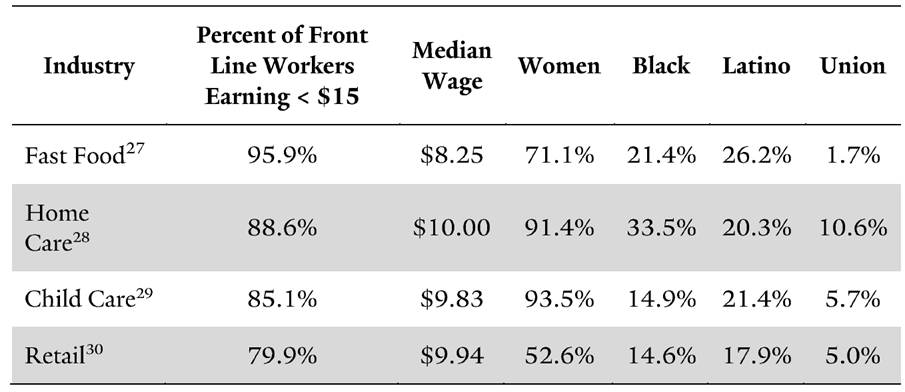

The membership of low-wage worker campaigns, such as the Fight for $15, the CLEAN Carwash Initiative,19 and OURWalmart,20 are defined just as much by these racial and gender dynamics, as by the fact that they are primarily low-wage service workers toiling in fissured21 workplaces and in positions that are often less than full-time or otherwise contingent.22 Their greatest numbers are in retail, food service, and healthcare (excluding hospitals)23—all industries directly affected by the globalized economy24 and exhibiting low unionization rates25—but they are also heavily employed in private households and other industries, such as transportation.26

table 2.

For these workers, the demand for higher wages and safe working conditions27 cannot be divorced from the need to address disparities in wealth, health, housing, and education that are tied to race, gender, class, geography, and immigration status.28 Many low-wage worker groups such as the Fight for $15, CLEAN Carwash Initiative, and the National Domestic Workers Alliance29 are therefore employing an intersectional approach to addressing their members’ multiple, layered identities. Respecting what Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw calls “the need to account for multiple grounds of identity when considering how the social world is constructed,”30 these movements recognize that poor workers are not defined by a simple lack of money, but by a collection of racial, ethnic, gender, geographic, and other identities with a corresponding variety of experiences of poverty that require more than traditional labor law to address.

While the lack of collective bargaining power in low-wage industries certainly plays a key role in perpetuating poverty, workers themselves attest that it is not the only factor contributing to their disenfranchisement. Fight for $15 worker leader Adriana Alvarez maintains that attaining $15 an hour and a union at work is paramount for the movement’s members: “I want to give the world to my son, but I can’t on minimum wage. I need a living wage.”31 But racial justice is equally a concern. According to Gabrielle Hatcher, “[a] lot of people here are wondering why we’re talking about racial justice, but racial justice and economic justice are really just two sides of the same coin here. As a woman of color, I’ve been passed up for promotions and higher-paying positions.”32 Immigration reform is also a high priority because, according to leader Adriana Sanchez, “[i]mmigrants make billions of dollars for the fast food industry, yet at the same time we are forced to live in fear in our jobs and in our communities.”33

The efforts of low-wage workers’ campaigns to improve wages and working conditions are therefore increasingly inextricable from their attempts to address the discrimination and injustices that worker leaders like Adriana Sanchez and Jorel Ware experience. In the next Part, we discuss the strategies that the low-wage worker campaigns are using to raise the visibility of low-wage workers within the broader labor movement, to challenge low-wage employers to improve working conditions, and to build workers’ political power.

II. low-wage worker movements are using legal and non-legal tools to reshape worker advocacy

The innovation in advocacy and labor law that Professor Andrias and other scholars have addressed is at once an attempt to grapple with the effects of the fissured workplace and a response to the problems affecting low wage workers outside their place of employment. As Andrias argues, “decentralized, private representation and bargaining”34 cannot fully address the obstacles workers face in today’s economy. Yet tripartite sectoral bargaining is also only part of the answer. Low-wage worker movements are going beyond traditional areas of bargaining and using numerous strategies to address various facets of inequality. Campaigns such as the Fight for $15 employ a host of strategies aimed at lifting up entire communities by organizing around voting rights, housing segregation, environmental pollution and climate change, access to healthcare, student debt, and other issues that affect low-wage workers. Workers’ advocates, worker centers, law firms, policy organizations, and labor unions across the country are all leading the way in developing innovative solutions to the problems low-wage workers face.

From these efforts, we see three broad, interlocking strategies that low-wage worker movements are using to respond to workers’ intersectional demands and that seek “to democratize control over workers’ lives and, more broadly, over the economy and politics.”35 The first is the aggressive and highly visible advocacy of labor standards and civil rights through legal and non-legal means, focusing on building broad awareness of working conditions. The second strategy is the formation of coalitions that bring together labor unions, policy organizations, and community groups to advocate for shared goals—from investment in environmentally-sustainable jobs to police accountability. These coalitions are forged both at the national level, where broad visions and goals can be set, and at the local level, where they can be most responsive to specific communities’ needs. The third and final strategy is local and state innovation, focused on moving local governments, agencies, and institutions to treat workers as key stakeholders.

1. Advocacy of Labor Standards and Civil Rights through Legal and Non-Legal Means

Low-wage worker movements have taken on low-wage industries once thought impervious to unionization.36As arguably the flagship amongst these movements, the Fight for $15 pursues a variety of legal and non-legal strategies to enforce labor standards and civil rights. Some of the Fight for $15’s legal strategies are well known, even iconic: mass actions and strikes;37 the New York fast food wage board;38 and NLRB joint employer litigation.39 Others are more legally conventional and smaller in scale yet still vitally important, especially for the workers directly affected: unfair labor practice charges to protect strikers from retaliation,40 employment law claims for wage theft and other FLSA violations,41 claims to correct workplace safety violations,42 and claims to address sexual harassment.43 The Fight for $15’s legal strategy thus encompasses a wide spectrum of legal disciplines including traditional labor and employment law, corporate law in support of corporate activism initiatives44 and even criminal law to defend strikers and protestors who are arrested while engaging in civil disobedience.45

The law, however, is not the only source of protection for workers active in these movements. One of the most powerful tools developed by the Fight for $15, for example, is the “walk back.” When Fight for $15 members return to work on their next shift following a strike, the standard practice is that they be accompanied to their worksite by a contingent of community members who engage in a public show of solidarity that lets management know the community supports the worker and the movement’s demands.46 This simple walk back to work gives the workers confidence and is credited with lowering the incidence of retaliation. The Fight for $15 has also employed fasting as a form of civil disobedience in an effective manner. Most notably, twenty-one-year old McDonald’s worker Anggie Godoy fasted for fifteen days in April 2015 to raise the Los Angeles city council’s awareness of low wages;47 shortly thereafter, the council voted to raise the minimum wage to $15 by 2020.48 These non-legal actions are characteristic of Fight for $15’s creative and multi-disciplined approach to worker advocacy.

2. Building Coalitions Locally and Nationally

Coalition building has been instrumental in low-wage workers’ campaigns because it broadens workers’ support base while linking workers to other issues and groups that they care about. At the local level, for example, coalition building has connected labor issues to immigration, police violence, and access to healthcare, as well as to issues that can sometimes feel remote to workers, such as NLRA remedies and preemption questions.

One salient example of linking labor to immigration issues, for example, is the work of the CLEAN Carwash Initiative. Through CLEAN Carwash, immigrant groups have joined worker centers and labor unions such as the United Steel Workers to take on abuses in Los Angeles’ car washes.49 DREAMers—undocumented Americans who were brought as children to the United States—have played an important role in this campaign by helping to deepen the relationship between the labor and immigration movements. As one DREAMer states, “as workers, day laborers, undocumented immigrants, and people, we were sharing tools for [the car wash workers] to defend themselves and become unafraid . . . and [continuing] to show that unity is power.”50 Working together, these groups helped secure the first union contracts with car washes in the entire country.51

The Fight for $15 has also made strides in linking the struggle for economic justice with that for racial justice. In Ferguson, Missouri, for example, the killing of Michael Brown brought renewed national attention to police violence and the issue of anti-Black racism. It was also in Ferguson that the intersection between class and race was cemented because Fight for $15—and fast food workers specifically—were at the forefront of the demonstrations for police accountability.52 Indeed, on West Florissant Avenue where Brown died and where most of the civil unrest took place, there is a McDonald’s restaurant.53 The workers in that restaurant are among the most active in the movement and overlap with the local Black Lives Matter leadership.54 As Rasheen Aldridge, a joint leader of the local Fight for $15 and Black Lives Matter movements, explains,

[o]ne key thing that connects both movements is poverty. If we had jobs in our communities that actually paid people a livable wage, not a minimum wage that isn’t even survival, we would get rid of crime and violence in our communities. People wouldn’t have to worry about the lights going off or about getting childcare.55

Through their commitment and solidarity the coalition between Black Lives Matter and the Fight for $15 was able to effectively channel the intersectional needs of Ferguson’s low wage community such that the Ferguson Commission appointed by the governor of Missouri formally recommended in its final report that the city’s minimum wage be set at a minimum of $15 an hour. 56

3. Local and State Initiatives

As the likelihood of federal pro-worker legislation has become more remote, states and cities are engaging in bold experiments both in litigation and legislation to raise labor and employment standards. Spurred by the change in the federal climate as well as the exhortation of low wage worker movements, states and localities are starting to find innovative ways to raise wages and benefits. 57 At Seattle’s SeaTac airport region, for example, the nation’s first $15 municipal wage ordinance was secured in 2013 through a ballot initiative58 supported by a broad coalition of union, faith, and community groups59 and enforced by Washington’s state supreme court.60 Six months later, the SeaTac ordinance served as a catalyst for the approval of a minimum wage policy by the Seattle City Council that established this city as the first in the country to mandate a minimum $15 wage.61 In New York, the 2015 fast food wage board that Professor Andrias lauds as a main example of tripartite sectoral bargaining instated a phased-in $15 minimum wage for fast food workers and addressed the problem of abusive scheduling,62 while in 2016 low wage airport workers at La Guardia and John F. Kennedy airports in New York were able to unionize and bargain for a phased-in $15 minimum wage.63

In all, twenty-one states raised their minimum wage in 201664 and four states now also have paid sick leave laws.65 Meanwhile, lawyers and workers’ advocates continue looking to mechanisms at the local and state levels to provide workers with family leave, child care, and paid sick days; to address wage theft, housing, and immigration issues; and to promote new forms of worker ownership and benefits. This upspring of support for low wage workers would not have come about without low wage worker movements employing a savvy media strategy that helped shape the public perception of their demands. Stories of individual workers in newspaper articles and on social media debunk myths about low wage workers; they reveal campaign leaders to be dedicated working parents and caregivers, students struggling with loans and tight schedules, and community members worried about their neighborhoods. Press coverage of Fight for $15 strikes by television, print, and digital outlets has boosted the movement by amplifying victories and building momentum.66 Indeed, it is in large part due to media coverage that low wage worker movements have been able to jumpstart the public discourse on economic inequality and become a normalized part of mainstream discourse, as evidenced during the 2016 primaries and election season.67

The three strategies set out above have worked because they center on the workers who are most negatively impacted by anti-worker policies, recognize the multiple forms of inequality that workers experience in the United States, and build power at the grassroots level. In the next Part, we focus on how a new unionism is emerging from these bold attempts to challenge inequality.

III. a new “common-good unionism” is emerging from the fight for $15 and other low-wage worker movements

Out of this innovation, a broad conception of worker welfare is emerging that moves beyond wages and benefits for its members, taking on the root causes of structural economic inequality.68 We call this “common-good unionism,” borrowing a term coined some public commentators to describe union-led campaigns that seek to address structural inequality for both workers and their communities.69 “Common-good unionism” results when unions bring their demands in line with the needs of the community, thereby benefiting not only union workers but all similarly situated workers across various geographies and demographics. As labor law practitioners we see that the demands of low-wage worker movements for greater equality for all workers have been critical to mobilizing workers across the country, and that new legal innovation flows from this commitment to democratic inclusivity. Robust community-based worker organizing, creative lawyering, and the formation of stakeholder coalitions are propelling this new labor movement.

The common-good labor movement is working cooperatively with a range of community allies on broad-based goals, which include closing the racial wage gap,70 regulating scheduling practices that destabilize workers’ lives,71 creating environmentally-sustainable jobs,72 stamping out sexual harassment and gender wage disparities,73 preserving and expanding health care,74 providing paid family leave and affordable childcare to all workers, and electing politicians who put workers’ interests before powerful business concerns.75 The Fight for $15, in particular, has foregrounded the connection between racial and economic justice. Dubbed the “new civil rights movement,”76 Fight for $15 has made combatting anti-Black racism a cornerstone of its national platform77 and has striven to address both government policies that disadvantage the Black working class78 and discrimination within the labor movement.79 One of the most concrete examples of this emphasis is Fight for $15’s collaboration with the Reverend Dr. William Barber II, the leader of the Moral Mondays campaign in North Carolina.80 At the 2016 Democratic National Convention, Reverend Barber gave a marquee speech on the role of Fight for $15 in strengthening democracy.81 Just a few days later, nearly 10,000 low-wage workers from fast food, home care, child care, airport, higher education, and other industries converged in Richmond, Virginia for Fight for $15’s first-ever national convention where Reverend Barber delivered the keynote address.82 In addition to “$15 and a union” and racial justice, Fight for $15’s national agenda also calls for affordable child care, quality long-term care, and immigration reform.83

Common-good unionism pushes the boundaries of what it means to be in a union and spurs worker movements to have significant impact on housing, education funding, health care, the environment, and other areas. Teachers’ unions throughout the country, for example, are using their power at the bargaining table to challenge foreclosures on the homes of school-age children, racial disparities in school discipline, cuts to arts education, and the lack of healthy food in schools.84In Pittsburgh, health care workers at the Allegheny City Jail teamed up with community activists to force the city to rescind a contract from a private company that had been operating the jail with unsafe staffing levels, leading to prisoner deaths and accusations of substandard care.85 As a result of a campaign, the county government took over medical care, improving conditions for both staff and inmates.86 In Los Angeles, a coalition of community and environmental groups and unions led by LAANE, Sierra Club, and the Teamsters, formed the Coalition for Clean and Safe Ports to get polluting trucks off the roads in order to reduce pollution in poor and immigrant communities.87 The program has helped poorer drivers—many of them minorities and residents of the most impacted neighborhoods who after expenses make an average of $29,000 to $36,000 a year88—afford newer trucks,89 with the goal of reducing emissions by 80%.90

In an exercise in common-good unionism, local unions are also providing members with much needed services. UNITE HERE Local 226, for example, provides its members in Las Vegas with a zero interest down payment loan through its Housing Partnership program.91 State labor councils are also increasingly promoting “labor candidate schools,” where union members can receive training and support to run for local offices and advocate for policies that improve working families’ lives.92

To be sure, low wage worker and allied movements face many obstacles in the immediate future.93 An anti-labor Republican administration and market forces will continue to challenge labor organizations.94 The Supreme Court will likely hear the successor to Friedrichs.95 Workers also face significant threats to crucial services: twenty million people may lose their health insurance,96 immigration raids are sowing fear in many communities,97 housing costs continue to rise in major cities,98 and Social Security and Medicare privatization may become viable legislative proposals.99 None of these challenges, however, should mean that workers demand less. On the contrary, the experiments and successes discussed above show that low-wage workers are right to demand much more—and that the more they demand, the more they win.

Low-wage workers’ success in raising the minimum wage has at times overshadowed the fact these campaigns have been spearheaded and developed by the workers most disproportionately affected by low-wage jobs. Workers currently earning less than $15—many of whom struggle with the very basics of survival such as having enough food, safe housing, and access to quality healthcare and education,100 in addition to the pernicious effects of structural racism, the gender wage gap, and economic segregation101—yearn for the control over their work and lives that unions afford. Seventy-two percent of low-wage workers in the United States support unions.102 Of course, the fact that these workers are clustered in a handful of remarkably difficult jobs in low-wage industries, from home-care work to airplane cleaning, is important.103 Unions reduce the gender104 and racial105 wage gap significantly in workplaces subject to collective bargaining, and increase union members’ understanding of and engagement in democratic processes.106 Low wage workers’ economic and political demands, born out of shared experiences of racism, sexism, poverty, and exclusion from the political process, thus provide the impetus for legal and strategic innovation.

Kimberly M. Sánchez Ocasio is an Assistant General Counsel and the Ethics Ombudsperson for the Service Employees International Union. Leo Gertner is a Law Fellow at the Service Employees International Union. They both wish to thank their families—Victor, Lyra, and Rachel especially—and their colleagues at the SEIU Legal Department for their continued encouragement and support.

Preferred Citation: Kimberly M. Sánchez Ocasio & Leo Gertner, Fighitng for the Common Good: How Low-Wage Workers’ Identities Are Shaping Labor Law, 126 Yale L.J. F. 503 (2017), www.yalelawjournal.com/forum/fighting-for-the common-good.